Полная версия

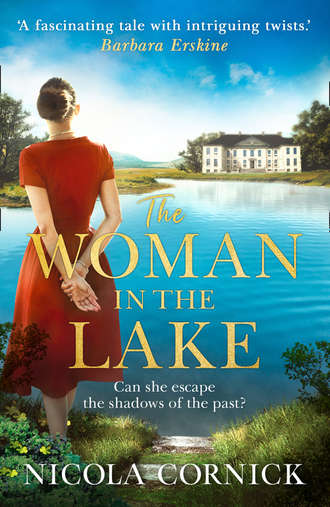

The Woman In The Lake: Can she escape the shadows of the past?

International bestselling author NICOLA CORNICK became fascinated with history when she was a child, and spent hours poring over historical novels and watching costume dramas. She studied history at university and wrote her master’s thesis on heroes. Nicola also acts as a historical advisor for television and radio. In her spare time she works as a guide in a seventeenth-century mansion.

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Nicola Cornick 2019

Nicola Cornick asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © March 2019 ISBN: 9781474064712

For Julia, a Swindon girl

Time flies over us, but leaves its shadow behind.

NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

Prologue

Eustace

April 1765

I know what they will say of me when I am dead. I will be cast as a madman and a fool. They will blame the divorce, so scandalous for a peer of the realm, and claim that it drove me to misery and delusion, that it turned my mind. They will rake up all the old gossip and call my wife a whore.

It pleases me that society will slander Isabella over again. I will gladly tolerate being painted a cuckold and a weakling if it hurts her. I wish I could hurt her more but she is beyond my reach now, more is the pity.

There are those who call me a wicked man. They are wrong. True evil requires intent and I never had the will or the cunning to be truly wicked. Only once was I tempted to commit murder and even then it was not my fault, for I swear I was possessed. It was the golden gown that moved me to evil and the gown that led to that most terrible mistake.

I remember the horror of it to this day. I still see the scene so clear before my eyes. She was walking ahead of me, through the dappled moonlight, and I recognised the gown and hastened my step. I swear I had no fixed intention, no thought of murder, not at that moment. I wanted to talk, to reason with her. Then, on the path by the mill, she seemed to stumble and fall and all of a sudden I was seized by the thought that this was my chance to be rid of the threat for ever. I could not bring myself to touch her directly so I nudged her body with my boot and she rolled gently, so gently, over the edge and into the pool.

I see it all again: the silver moon swimming beneath the water and the golden gown billowing out about her like a shroud slowly unfurling. I needed to claim that gown but my fear made me clumsy and I ripped it from her body when it would not yield to my hands. And then…

I break out into a cold sweat whenever I remember. Everything is so vivid. The sweet scent of lime blossom mingled with the stink of dank weed from the millpond, the endless roar of the water over the sluice like the rush to bedlam.

And then… The body rolled over in the water and I saw her properly for the first time in the moon’s reflected glow. It was not the face of my nemesis. I stood there with the gown dripping in my hands and then I was sick; sick with revulsion, sick with fear, sick with disappointment.

Binks came upon me as I knelt there, retching up my guts.

‘I will attend to this, Lord Gerard,’ he said, as though he were my butler tidying away a glass of spilt wine. ‘You should have left it with me, as we agreed.’

Binks was a damned impertinent fellow but a useful one and I was not going to argue with him. I took my carriage back to Lydiard House and I sat here in my study and drank more than I had ever taken before. I was out cold for three days.

When I came to my senses the first thing I saw was the golden gown draped across the end of my bed like a reproachful ghost. I wanted to be rid of it, to burn it, rip it to shreds or give it to the first beggar woman I saw but at the same time I was too afraid; afraid that somehow, some day, it would return to haunt me. My only safety lay in keeping it close to me. Wherever I went the gown came with me, wrapped up tightly, hidden away to contain its poison, but with me all the same. And that is how it haunted me for ever after. That is how it has possessed me, in mind and body.

I have no notion what happened after I left Binks to do the work that I dared not do. I heard reports of the tragedy of course, for the servants were full of the story and it was in all the local newspapers. It was a famous scandal that respected Swindon banker and businessman Samuel Lawrence had drowned his wife in the millpond and then apparently taken his own life, following her down into those dark waters.

In time I almost came to believe those stories myself.

Except that for as long as the gown is with me, I will remember the truth. I will remember Binks, who disappeared like a will-o’-the-wisp once the deed was done, and I will remember Binks’s men, the Moonrakers, hard men, smugglers, criminals. I have lived in fear of them these past twenty years for I know they hate me for killing one of their own. My life is so much more precious, infinitely more important than theirs, and yet I live in fear of a gang of felons.

From the drawing room window I can see the lake here at Lydiard Park glittering in the morning sun. On the days when I am too drink-sodden and addled to walk, the steward places me here, telling me that it will raise my spirits to see the world outside. Little does he know that nothing could cause me more pain than to look upon the shining water. Or perhaps he does know it, and places me here to torment me. Perhaps he hates me too.

The Moonrakers will come for me soon. This morning I received a token from their leader. It was such a beautiful gift, an inlaid box. I unwrapped it with greedy excitement until I saw the tiepin inside with the design of a hanged man, the word ‘remember’, and the initials C. L. Then I dropped it and it went skittering away across the floor propelled by my revulsion.

She need have no fear. I shall never forget that day. The gown will remind me. It will possess me to my last breath.

The sun swims under the rippling water and the day turns dark. The Moonrakers are ready. Ready to fish for their fortunes again, ready for time to repeat itself, ready for the secrets to be told.

Chapter 1

Fenella

2004

She could never forget the day she stole the gown.

Twenty-three of them visited Lydiard Park that day. It should have been twenty-five but Emily Dunn had chickenpox and Lauren Featherstone’s parents had taken her on holiday to Greece despite the fact that it was still term time, and Mrs Holmes, the headmistress, disapproved. Mr Featherstone paid the fees, though, so Mrs Holmes kept quiet.

There were three teachers as well, not that many to keep them all under control. Two of them looked harassed – Miss Littlejohn always looked harassed, and Mr Cash didn’t really like children much – they all knew it even though he never said so – but Miss French was all relaxed and smiley. Miss French was cool, more like a big sister than a teacher.

‘Just one more room to visit, girls,’ she coaxed, when they all started to drag their heels due to heat and tiredness and endless stately home corridors, ‘and then we can go to the tearoom and the shop.’

Fen didn’t have any money to spend in the shop because her grandmother had forgotten again. She wasn’t sure if anyone remembered to pay her school fees either but until someone said something she was stuck at St Hilda’s and that was fine. She’d been to worse schools, plenty of them, some of them boarding, some not. She made friends quickly and easily because she’d learned how. It was either that or forever be the loner, the outsider, the one who came and went without leaving a trace.

‘Fen,’ Jessie, her best friend, all brown curls and bossiness, was pulling on her sleeve. ‘Come on.’

But Fen lingered in the state bedroom as the gaggle of schoolgirls in their red and white summer dresses and red blazers went chattering through the doorway into the drawing room. As soon as they were gone the silence swept back in like a tide, cutting her off. It was odd, as though a thick door had slammed somewhere separating her from the rest of the world. She could hear her own breathing, feel the sun on her face as it fell through the high windows to speckle the wooden floor.

It wasn’t a room that appealed to her at all. Her bedroom in her grandmother Sarah’s house in West Swindon was quite small, painted pale green and had an accumulation of vintage bits of china and glass and other small pieces that Sarah had encouraged her to buy on their trips to the flea markets and car boot sales. This huge space with its flock wallpaper, soaring white pillars and four poster bed with its embroidered hangings seemed completely lifeless. It was no one’s room, merely a museum. The whole place felt empty to her and a bit creepy; the other rooms held waxwork figures in period dress that had made her shudder. The other girls had giggled over them but Fen had imagined them as zombies or automatons come to life, stalking the corridors of the old house.

There was a door in the corner and beyond it a room that looked to be full of light. It beckoned to her. Fen peeped inside. It was small, oval-shaped, painted in blue and white like the Wedgwood vases that her grandmother collected. What caught her eye, though, was the stained glass window with its tiny little painted panels depicting colourful pictures of fruit, flowers, animals – was that an elephant? – something that looked half-man half-goat, a ship to sail away in, a mermaid… The window enchanted her.

She stretched out a hand towards the light, wanting to touch those bright panes and experience that vivid world but before her fingers touched the glass there was the sound of running footsteps behind her.

‘Fen! Fenella! Where are you?’

It was Jessie’s voice, anxious and breathless now. Fen dropped her hand and turned quickly, hurrying back through the door of the closet into the bedroom beyond. Jessie was not there. Everything looked the same, as empty and lifeless as before. And yet on second glance it did not. It took Fen a moment to realise what was different. The shutters at the windows were now closed and the lamps were lit; they smelled unpleasantly of oil and heat. Perhaps one of the curators had come in whilst she was in the blue closet and had decided to block out the bright sun in case it damaged the furnishings.

That was not the only difference though. The bed was rumpled, covers thrown back, and the wardrobe door was half-open, revealing shelves of clothes within that looked as though they had been tossed aside by an impatient hand. All of a sudden the place looked lived in rather than frozen in time. It was an unsettling feeling; instead of making the house seem more real, it gave Fen the creeps. Looking straight ahead, she was aware that her heart was suddenly beating hard but was not quite sure why. She walked quickly through into the drawing room to find the rest of the pupils.

In the drawing room the differences were even more marked. There was a fire burning fiercely in the grate even though here the shutters were thrown back and the room was in full sunlight. It was so hot and airless that Fen felt the sweat spring on the back of her neck and trickle uncomfortably beneath her collar. The whole house was as quiet as a sepulchre. It was uncanny.

Over the high back of one chair, shimmering in the light with a soft, golden glow, was the most beautiful dress Fen had ever seen. She stared at it. It felt almost impossible to tear her gaze away. She did not even realise that she had started to move towards it; her hand was on the material and it felt as soft as clouds, lighter than air, a trail of silver and gold spangled with stars.

‘Pound? Where the hell are you, man?’

Fen had not seen the figure sitting before the window, almost hidden by the high curved back of a wing chair. She jumped at the crack of his voice and spun around. He was fair, florid, dressed in a wig and poorly fitting jacket with some sort of scarf wound carelessly about his neck and a waistcoat flapping open. He looked bad-tempered and drunk. Fen was only thirteen but she knew an alcoholic when she saw one. She could smell the fumes on him from where she was standing. Nevertheless she opened her mouth to apologise. He was probably a re-enactor of some sort, or a room steward, although really it didn’t seem appropriate to have drunks in costume wandering about the place.

‘I got lost—’ Quick, facile lies came easily to Fen, they were her survival tactics. But the drunk wasn’t looking at her, more over her shoulder towards the doorway.

‘Pound!’ the man roared. ‘Damn you, get in here now and pour me more wine!’

There was a bottle on the table, Fen saw, cruelly placed either by accident or design just out of his reach. He lurched forward and almost fell from the chair, clutching at the sides to steady himself. She saw his face clearly then; the vicious lines drawn deep about the mouth, the pain and frustration and anger in the eyes. Panic seized her. She wondered if she had unwittingly stumbled into some sort of performance put on for the visitors. Yet that didn’t feel right. There was no audience apart from her and the intensity of the man’s fury and desolation seemed all too visceral. She needed to get out of there.

‘Take me…’

The golden gown seemed to call to her. She felt the allure of it and was powerless to resist. The impulse was so strong and so sudden that she reacted instinctively. She grabbed the gown and ran, fumbling to push it into her rucksack, her feet slipping and sliding on the wooden floor. She was panting, her heart thumping, and she stopped only when she burst through the doorway into the hall and saw the startled faces of staff and visitors turned in her direction.

‘Fenella Brightwell?’

A woman with iron-grey hair and an iron demeanour, a museum piece herself, marched up to her.

‘Yes,’ Fen said. Her mind was still grappling with what she had seen; with the violence and the anger. Were they making a film? How embarrassing if she had accidentally wandered onto the set mid-performance. She would never live that down. Everyone would be laughing at her. No doubt the iron woman was about to tell her off.

‘We’ve been looking for you everywhere,’ the woman said. Her grey eyes snapped with irritation. ‘The rest of your group have gone back to the coach. If you run you might catch them.’

‘What? Oh, thank you.’ Fen was still distracted by the scene in the drawing room and the old man. There had been something pathetic about his impotent desperation.

‘Excuse me,’ she said, very politely, ‘but is there some sort of film being made in the drawing room? Only there was an old man sitting in a chair by the window and I thought—’

‘It’s forbidden to sit on the furniture,’ the woman said. ‘How many times do I have to tell people?’ And she stalked off towards the drawing room.

Fen hoisted her rucksack onto her shoulder and went outside. It was a relief to be out in the fresh air. There had been something smothering about the room and its occupant, brim-full of anger and misery.

She started to walk up the wide gravel path through the woods. She had no intention of running all the way back to the car park. The coach wouldn’t go without her. The teachers would get into too much trouble if they did.

She looked back at the house. There were visitors milling around in the drawing room. She could see them through the glass of the sash windows. The chair looking out over the gardens was empty. It was odd that the drunk had disappeared but perhaps the iron-grey woman had thrown him out already. He was probably homeless or care in the community, or something. She had more pressing things to think about anyway, such as the need for a plausible excuse for where she had been so that the teachers didn’t get cross with her.

‘You got locked in the lavatory!’ Miss French said, eyes lighting up with amusement, as Fen clambered aboard the coach and made her apologies. ‘Oh, Fenella! Only you!’

Even harassed Miss Littlejohn relaxed into a smile. Mr Cash didn’t; he looked hot and annoyed and had been searching the gardens for her. He didn’t look as though he believed her either but Fen didn’t care.

‘I looked for you everywhere,’ Jessie whispered, as Fen slid into the seat next to her. ‘How did you get out?’

‘They had to break the door in,’ Fen said. ‘The lock had jammed. They sent for a carpenter.’ She smiled. ‘He was cute.’

‘Fen was rescued by a cute carpenter,’ Jessie said, giggling, to Kesia, who was sitting across the aisle. Word went around the coach. Soon everyone was hanging over the back of the seats or crowding the aisle, wanting to know what her rescuer had looked like.

‘Sit down, girls,’ Mr Cash snapped. ‘You’re a health and safety hazard.’

There was more giggling at that.

The coach dropped Fen off at the end of her grandmother’s road. No one else from school lived in The Planks, although the houses were very nice. Most of the girls lived in the picture postcard villages outside Swindon rather than in the town itself. There was always a slight drawing back, eyebrows raised in surprise, when Fen mentioned that she lived in town so she never told anyone.

When she pushed open the back door she could hear the sound of the television, very loud. It was four thirty. Her grandmother would already be halfway down her second bottle of wine by now, watching the afternoon soaps with her spaniel, Scampi, sleeping next to her. Fen didn’t interrupt her. Her grandmother was a happy drunk but not if someone disturbed her when she was watching TV. Anyway, she had homework to do, an essay on the visit to Lydiard Park, but that could wait. She rummaged in her coat pocket and took out a battered copy of Bliss magazine that she had found under Kesia’s seat in the coach and lay back on her bed with a contented sigh. She thought that Kes had probably dropped the magazine accidentally rather than finished with it but her loss was Fen’s gain. She’d give it back when she had read it since Kes was her friend.

At five o’clock the living room door banged and there were footsteps on the stairs.

‘Fenella!’

Her grandmother never called her Fen. She thought it was common to shorten people’s names.

‘Darling!’ Her grandmother rushed in and wrapped her in a wine and patchouli scented hug. ‘How was the trip? Did you have fun?’

‘It was great, thanks.’ Fen never told her grandmother anything significant. She had learned long ago only to give adults information on a need-to-know basis. Perhaps the lesson had been learned when she had first tried to explain to her mother about her grandmother’s drinking.

‘We all like a glass of sweet sherry now and then, Fenella,’ her mother had said on a crackly telephone line from Patagonia, where she had been leading an archaeological dig. ‘Don’t worry about it. Your gran is fine.’

It was then that Fen had realised she was on her own. Her father had run off with one of his PhD students when she was only seven; they didn’t talk anymore, in fact she had no idea where he was, or even if he was dead or alive. One of her brothers was at boarding school, the other on a gap year in Malawi. Her elder sister, Pepper, was with their mother in Argentina, working as an unpaid assistant on the dig. Fen couldn’t tell either Jessie or Kesia about her gran, even though they were her closest friends at school. They might laugh at her or tell other people. It was too much of a risk.

‘I must show you the bracelet I bought in a charity shop this afternoon,’ Fen’s grandmother was saying. ‘I’m sure they’re real rubies, and nineteenth century too!’

‘Well, you never know,’ Fen said, squeezing her hand. She felt a rush of affection for Sarah. Her grandmother had been there for her when everyone else had buggered off and left her, and that counted for a lot even if it meant that Fen was looking after Sarah most of the time rather than vice versa. Besides, she knew that Sarah was sad. Fen didn’t remember her grandfather, who had died when she was only three, but by all accounts he had been a wonderful man as well as a rich one. Once widowed, Sarah had had plenty of suitors, as she quaintly called the men who were after Granddad’s money, but none of them held a candle to him.

‘What’s for tea?’ her grandmother asked now. With a sigh, Fen put aside the magazine and stood up. She knew she had better find something or it would be a tin of baked beans again.