Полная версия

The Way We Eat Now

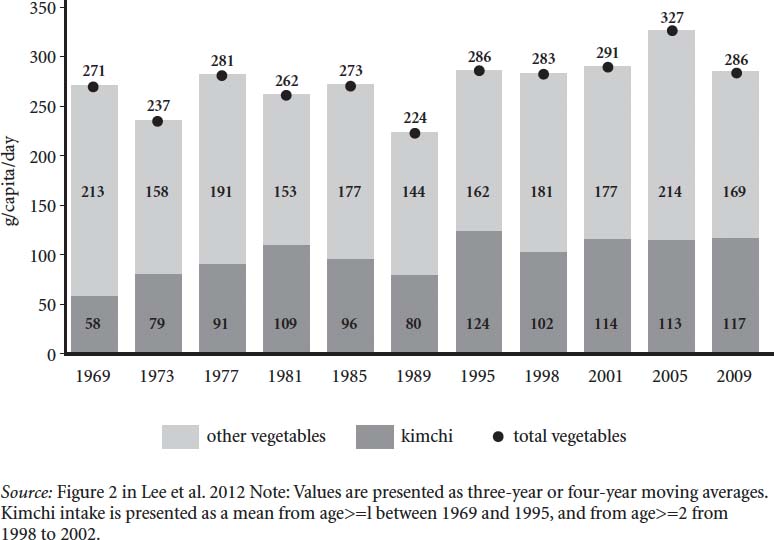

How did South Korea manage to retain its vegetable-eating ways, despite all the other transformations and pressures of modern life? Part of the explanation is cultural. South Koreans see vegetables as something delicious rather than merely healthy, as we all too often see them in the West. Koreans enjoy a greater variety of flavoursome vegetables than most eaters in other countries, from bean sprouts to spinach. In rural Korea, it has been estimated that as many as three hundred different vegetables are eaten, each prized for its distinctive flavour and texture. King of all vegetable dishes in Korea is kimchi, a kind of fermented and highly spiced cabbage, which is not just a condiment but a staple food, the most consumed single item in the diet after rice, as of 2002.61

If Korea was helped by its vegetable-loving food culture, it also benefited from a range of government initiatives which consciously set out to soften the blow of the nutrition transition. In contrast to other developing countries, South Korea made a more concerted effort to protect its own cooking against the new globalised diet. From the 1980s onwards the Rural Living Science Institute trained thousands of workers to provide free cooking workshops educating families in how to make traditional dishes such as steamed rice, fermented soybean foods and kimchi.62 In addition, there were mass media campaigns to promote local foods, with TV programmes emphasising the higher quality of local food and the benefits of supporting home-grown produce and local farmers. When most children in the 1980s switched on the TV, they would be greeted by adverts for sweets and treats, fizzy drinks and cereals. When Korean children watched TV, they might instead be fed with government-endorsed messages on the benefits of locally grown food.63

Fast forward to the present day, and the average South Korean diet is no longer quite as healthy as it was in the 1990s. When Popkin returned to look again at the data on Korean diets in 2009, he found that consumption of both alcohol and soft drinks was on the rise. From the late 1990s to 2009, the Korean government put a decade of effort into promoting the consumption of wholegrains, yet the average person only ate around sixteen calories more of wholegrains than before. The message this time was less effective. The prevalence of obesity, diabetes and heart disease in South Korea were also much higher in 2009 than ten years earlier.64

Vegetable consumption in Republic of Korea, 1969–2009, grams per person per day.

Yet Koreans still eat far more vegetables than people in most other wealthy countries and kimchi is as popular as it has ever been. This is all the more remarkable considering that the price of cabbage – the main ingredient in kimchi – rose by 60 per cent between the 1970s and 2009. The average South Korean diet might not be perfect – what human diet ever has been? – but South Korea remains as remarkable proof that it is possible to attain some kind of golden midway point between the wholesome but too-scarce diets of the past and the plentiful but unhealthy diets of the present.65

What South Korea shows is that the curve of the nutrition transition can be bent, at least slightly, with the right interventions from government. This offers hope to the developing countries of sub-Saharan Africa. Perhaps they, too, will be able to retain the best aspects of their vegetable-centric and varied diets while enjoying lives of greater comfort, wealth and ease.

At the time of writing, however, it is doubtful whether the governments of other developing countries will follow the South Korean route in actively trying to fight the onslaught of packaged foods. The more common approach seems to be for governments not so much to fight the nutrition transition but to try to make it curve faster, to gain from the profits of multinational food companies.

In August 2017, I was in Copenhagen for the World Food Summit, a two-day conference aimed at finding better ways for the world to feed itself. One of the speakers was Harsimrat Kaur Badal, the Minister for Processed Foods in India’s government (I never knew such a job existed). Badal stood up and gave a passionate speech lamenting the Indian attachment to freshly cooked food made from fresh vegetables. India, she said, was a country where most people still ate three home-cooked meals a day. The audience of Danish and international food writers, chefs and representatives from the food industry let out a mild sigh of envy. Oh for the fresh-cooked food of India! But the minister was trying to explain to us that this fresh and delicious food was actually a very bad and wasteful thing. ‘We only process 10 per cent of the food we produce in India,’ she lamented. She compared this to the countries of Western Europe, where around 60 per cent of food is processed. The minister made the point – quite reasonably – that the middle classes in India wanted to eat the same foods that were available to people with money in the rest of the world. She also pointed out that India wastes $40 billion worth of food every year, mostly because of inefficient distribution networks. ‘Food waste is morally wrong.’ The answer, she suggested, was foreign direct investment (FDI) in processed food.

India was a gigantic business opportunity, the minister explained. It was a market of 1.4 billion people, whose potential as consumers of processed food was still largely untapped. ‘I invite you all to come and partner with my country,’ she announced. ‘We want you to teach us your Danish technology and knowhow.’ In return, she offered India’s amazing ingredients and a ‘platform’ of customers ripe for the picking.

Is this really the route that the governments of India and other developing countries want to take through the nutrition transition? India is a country with a long-standing love of vegetables, which has the potential to experience something like the South Korean version of stage four, rather than the health-destroying version seen almost everywhere else. Rising incomes in India are a wonderful and life-changing thing, on so many levels. But already, as India welcomes more ultra-processed food into its diet, the country is seeing an alarming rise in type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance. Is there a way for India to enjoy life beyond hunger without having to suffer the diseases of affluence?

What we ate next

Based on everything we know about history, stage four will not be the final phase of the nutrition transition, but no one can say for sure what future diets will look like. One thing that seems certain is that after fifty years or more of over-consumption there will have to be some kind of shrinking back in the amount of calories populations consume. What remains to be seen is whether this reduction will be forced upon us by climate change and failing harvests, or whether we can take control of our own food destiny and start to eat within the limits of what our bodies need and what the land can bear. Barry Popkin is among those who predict that with the right policies the latter can happen and we will leave behind stage four for stage five, a phase of life that he has christened ‘behavioural change’.

Stage five – if it ever fully comes into being – is where the hope lies. During this phase, most people would still be affluent and live in cities, but the cities would take on different characteristics, with more opportunities for physical exercise and more accessible and affordable fresh produce. This stage would be characterised by people eating more vegetables and fruits and experiencing a rapid decline in degenerative diseases. During this phase, greater knowledge of the links between diet and health would lead people to eat better diets. Phase five is where we would all like to be living and eating: a comfortable life with neither hunger nor disease, with delicious food but not an excess of it.

There are little glimmers that stage five may be emerging – not everywhere and for all people, but in enough places that it starts to look a bit like the future. One of those places is Denmark.

‘So much has happened in twenty years. It is unbelievable how exciting it is to be a cook right now!’ exclaims Trine Hahnemann, a caterer and cookbook author based in Copenhagen. I meet Hahnemann at the same World Food Summit in the summer of 2017 where I hear the Indian Minister for Processed Food speak. Hahnemann takes me to a wine bar in one of Copenhagen’s many beautiful old townhouses where we drink Grüner Veltliner white wine from elegant Scandinavian glasses with long stems and flattened bulbs. She tells me how she sees good food as central to the quality of life in general.

As a Dane, Hahnemann’s experience of modern food is completely different from that of her middle-class equivalent in Mumbai or Delhi. Denmark passed from stage three to stage four of the nutrition transition in the 1950s and 60s. Now, it is heading somewhere altogether more flavoursome and interesting. If stage five exists anywhere, it is surely in Copenhagen, where the majority of adults cycle to work and the food culture centres on dishes which are healthy, sustainable and delicious. As in South Korea, Denmark benefits from a government that takes the quality of its citizens’ diet seriously. In 2004, Denmark placed a blanket ban on trans fats in foods for sale, a move that played a part in reducing the country’s rates of heart disease.66

When Trine Hahnemann was a child, no one in her Copenhagen school had heard of garlic. She remembers how long it took for houmous to be accepted by conservative Danish tastebuds. ‘Yet now,’ she remarks, ‘you couldn’t go to any food store and not find houmous. That’s in thirty years. That’s diversity.’ A mere ten years ago, there was no Vietnamese food to be found in Copenhagen, whereas now there is a passion for pho, a spicy Vietnamese broth heady with green herbs and vegetables. Yet the Danes have also retained their love of healthy traditional foods such as dense dark rye bread.

As someone who caters for government-funded work canteens, Hahnemann has seen first-hand how the Danish government makes healthy and sustainable eating a priority for everyone in society, rich and poor. As of 2016, a new law came in requiring that any food served in a public institution – from a school to a hospital – must be 60 per cent organic. Hahnemann finds that the Danes she cooks for are remarkably receptive to vegetables and flavourings which would once have been seen as threatening. If a big batch of cauliflower arrives from her suppliers, she may serve it three days in a row: day one with a brown butter sauce, day two as Indian pakoras and day three Italian-style with capers.

Despite Hahnemann’s love of vegetables, not everything she cooks and eats would be defined by a nutritionist as strictly ‘healthy’. Like most Danes, she adores cake and always keeps a sponge cake in her freezer in case friends drop by and she wants to rustle up a quick rhubarb and chocolate layer cake, filled with a rich rhubarb cream and topped with chocolate ganache. ‘Life without cakes would be a bit too sinister,’ Hahnemann writes in one of her cookbooks, adding that she believes cake to be good for mental health. Just as the Japanese-style diet eaten by Fumiaki Imamura is a mix of ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’, so is the modern Danish diet. But the balance, in both cases, is tipped towards the healthy.67

Not every country can be like Denmark, which benefits from a tiny population, substantial wealth and low levels of social inequality. It would be difficult to replicate exactly the way that the Danes eat anywhere else. The question, however, is whether other countries could shift to a phase where the typical diet is abundant but no longer damages the health of millions.

There are small but growing signs that many people around the world are moving in something like a Danish direction with food. Fumiaki Imamura’s data shows that the quantity of healthy food being eaten in the more affluent countries of the world – in Europe, North America and Australasia – is actually going up, while consumption of unhealthy foods slowly starts to level off. This chimes with the behaviour around food we can observe all around us, with many consumers consciously reacting against what they see as a toxic food supply and searching for new ways of eating. Who would ever have predicted the day when kale and beetroot would become objects of affection in the West? Food preferences can change in a remarkably short space of time.

The hope held out by stage five is that the two stories of modern food could merge into one, single story: a cheerier and more consistent one. We abolish hunger, eat our greens, make water the default drink, discover delicious things like houmous, have the occasional slice of cake for our mental health and live happily ever after. With the right food policies – which would include a combination of different farming policies, better food education and tighter regulation of unhealthy foods and drinks – we might yet reach stage five. For this to happen, governments would have to reset the trajectory of food policy away from the post-war agenda of quantity at all costs. There are tiny signs that this is happening, for example in the sugar taxes that have been enacted in various countries, but the true potential of food policy to improve our diet has yet to be tested. As the authors of one briefing paper on future diets from 2014 remarked, ‘policies on diets have been so timid to date that we simply do not know what might be achieved by a determined drive to reduce the consumption of calories, and particularly the consumption of fat, salt and sugar’.68

In the meantime, for those of us still in the middle of stage four, it can be hard to know how to live and eat for the best. We are beset on all sides by extremes – from fad diets on the one hand to junk food on the other – and it can feel almost impossible to steer our own path through the madness and choose a variety of foods that give us both pleasure and health.

It would be a start if we could at least name the food in front of us and notice what it is that we are putting in our mouths. Half the time, we do not even seem to recognise the ways in which our food has changed.

Colin Khoury, the diversity expert who identified the Global Standard Diet, told me about a dinner table game he plays at his home in Denver. Khoury lives with his wife and disabled brother and all three play the game every evening when they eat. It’s a kind of secular grace. Before taking the first mouthful, the three of them compete to name the species and botanical family of all the foods they are about to eat. In Latin. If they are eating burritos, for example, one of the Khourys might start by saying thanks for Triticum aestivum (wheat, in the tortilla), in the grass family (Poaceae). Then another person another might say, ‘Persea americana, avocado, in the laurel family (Lauraceae).’ They keep going until no one at the table can name any more ingredients. And then, the three of them eat. ‘It’s kind of a silly exercise,’ says Khoury, ‘but for me it’s a chance to pull it apart enough to be recognisant of what’s in a meal.’ Khoury’s dinner table game is a small but eloquent gesture against a world converging on the same unbalanced diet.

Personally, my Latin is not good enough to play this game. But I like Khoury’s idea of picking apart the components of food on a plate as a way of paying attention to what you are actually eating. This is what omnivores have always done: we look at a range of items and say ‘this is edible’ and ‘this isn’t’. None of us can escape living and eating in the global market of stage four. You can’t increase the variety of your daily food intake simply by naming it. But if we are going to tip the balance of our diets back in a better direction, it helps if you can at least say what it is that you are eating.

One of the problems with modern eating is that we stopped trusting our own senses to tell us what to eat. We may not be hunter-gatherers, nor even farmers. But every human is still an eater, and we still have senses that can tell us useful things about what to put in our mouths, if only we pay attention. You are under no obligation to eat something just because a packet tells you it is ‘all-natural’ or ‘protein-boosted’ or supposedly marvellous in some other way. Despite all the transformations of stage four, some things remain constant in our eating lives. Food is only food when a human says it is, and that human is you.

2: Mismatch

‘Sometimes we need to step backwards.’ Thus begins one of the many voices on the internet suggesting that our eating would be healthier and happier if only we could travel in time and eat a bit more like our great-grandmothers. This particular article – from the Institute for the Psychology of Eating – goes on to recommend ‘ancestral eating’ as the solution to many of the health problems of modern times.

What, you may ask, is ancestral eating? Apparently, it means sticking as closely as possible to the diet of your great-grandparents, wherever they happen to have lived. If your ancestors came from Greece, ancestral eating might entail full-fat yoghurt, wild greens, grass-fed meat and olive oil; if your family came from Japan, it might include fish, seaweed, fermented vegetables and ‘heirloom’ grains.1

Nostalgia for the tastes of our childhood has always been a powerful emotion. In our modern food environment, many of us invoke the wisdom of our grandparents as a way out of the craziness and ill health of modern diets. The inspiration for much of this way of thinking comes from the food writer Michael Pollan, who memorably advised that a good rule of thumb for healthy eating was ‘Don’t eat anything your great-grandmother wouldn’t recognise as food.’

The urge to turn back the clock on modern diets is understandable. So many aspects of our diets have worsened in recent decades. In all regions and in all countries, diets rich in coarse grains, legumes and other vegetables are disappearing as a mainstream way of eating and, as we saw in Chapter 1, there has been a great loss of biodiversity. It’s true that almost anyone in the modern world would be nutritionally better off eating more olive oil, more vegetables, more fish, more lentils, more wholegrains.2

Yet there are significant problems with thinking that the solution to poor diets is to go backwards. For one thing, our great-grandmothers often suffered terribly for the food they made, as they toiled to grind enough grain to keep their families alive. Until recently, it was common for women in much of the world to suffer from severe arthritis in their upper bodies, caused by the hours they put in at the grindstone, and rolling dough for such staples as chapattis and tortillas.

Moreover, not all great-grandmothers were eating an ideal diet. Many of our recent ancestors, as we’ve seen, were eating an extremely monotonous diet of grains and teetering on the brink of hunger. True, your great-grandmother wouldn’t recognise ‘sports drinks’ or popcorn fried chicken or any of the myriad other new highly processed foods, but she also might not recognise many of the wholesome new foods that contribute to health: raw kale salad and overnight oats and pumpkin seeds. Some great-grandmothers, moreover, were eating an early twentieth-century version of junk food. In 1910 a public health campaigner in New York City watched school children buying hotdogs dyed with violently pink food colouring and frosted cupcakes. It’s simply not true that our great-grandmothers would only recognise meat that was organic or grass-fed.

There is yet another difficulty with calling on the wisdom of our great-grandparents to save us from the worst excesses of modern food. This way of thinking ignores the fact that we are already living and eating with one foot in the past. Many of our most profound problems with eating stem from our inability fully to adapt to the new realities of the nutrition transition. In many ways, we already are eating according to the wisdom of our great-grandmothers, whose physiology and attitudes to eating were forged by the constant threat of scarcity.

What we eat may have radically changed in our lifetimes, but our food culture has not changed quickly enough to keep pace. We may, sadly, have forgotten the recipes of our great-grandmothers. Most of us have lost their home-spun knowledge of how to bottle fruits for the winter, not to mention their brilliance with a carving knife. But what we have not forgotten is their excitement at a laden table. We are living in a world of perpetual feast but with genes, minds and culture that are still formed by the memory of a scarce food supply. This is part of what it means to live through the vertiginous changes of stage four. We haven’t yet developed the new strategies for living that would enable us to navigate our way through this forest of seeming plenty to a way of eating that gives us both health and pleasure.

Think about some of the eating strategies that would have made sense in an era of scarce food. For one thing, you would value energy-dense foods such as meat and sugar very highly and gorge on them when they came your way – just as many of us still do. You would leave a clean plate and when food was accessible, you would grab it while you could.3

Development experts speak of ‘mismatch’ in explaining the clashes between the new food reality and the persistence of a human biology and culture adapted to earlier times. Instead of looking backwards to some imagined past which we can never reclaim, we need to look forwards and have yet another change of taste.

Our food system is currently full of mismatches. Some of these mismatches are cultural, as we fail to adapt to the new realities of eating in an age of abundance. Our food culture remains far too misty-eyed about sugary foods, for example. We haven’t adjusted emotionally to the fact that sugar is no longer a rare and special celebration food, worthy of devotion. Nor have we yet modified our attitudes towards those who are overweight and obese, to reflect the fact that these people are now in the majority.

Perhaps the most tragic mismatches are biological, as bodies formed for an environment of scarcity have not adapted to cope with the strange and bountiful new world we now find ourselves eating in.

The thin-fat baby

It was 1971 and Dr Chittaranjan Yajnik was a young medical student training at Sassoon General Hospital, Pune, a big city in the west of India. Yajnik was given the task of measuring the body mass index (BMI) of diabetic patients. This should have been a routine job, little more than number crunching. The main challenge was that Yajnik could not afford a calculator, so he laboriously wrote down the patients’ weight in pounds and height in feet in a log table and used his paper notes to calculate in his head the BMI in kilograms per metre squared.4

After taking measurements for the first ten patients, Yajnik noticed something was not right about his numbers. His medical textbooks had taught him that type 2 diabetes was a disease mostly suffered by the old and the obese. But the first ten diabetic patients that Yajnik measured in the hospital at Pune were all young and thin, with low BMIs. If his measurements were correct, then the textbook must be wrong, or at least incomplete, in its definition of type 2 diabetes as an offshoot of old age and obesity. Yajnik tried to raise the problem with his medical supervisor but was told that this was no time to be challenging medical orthodoxy – he should just focus on passing his exams.5

Yajnik could not put the puzzle of diabetes in India out of his mind. After some years studying Western diabetes in Oxford, England, he returned to Pune as a fully qualified medical researcher, by which point diabetes was on the rise in his home country. In the early 1990s, Yajnik began a study following mothers and their babies in six rural villages near Pune – the Pune Maternal Nutrition Study. The data he started to gather confirmed his hunch that diabetes in India had a very different face from the supposedly classical type 2 diabetes in the textbooks. Yajnik took detailed birth measurements of more than six hundred Indian babies and compared them with a cohort of white Caucasian babies born in Southampton in the UK. Compared to the UK babies, the Indian babies were smaller and lighter. Yet when Yajnik used calipers to measure the thickness of the babies’ skinfolds, he found that the small Pune babies were actually fatter than the Southampton babies – they were surprisingly ‘adipose’, especially around the centre of the body. Yajnik coined the phrase ‘the thin-fat Indian baby’ to describe this phenomenon. Even at birth, these Indian babies had higher rates of pre-diabetes hormones in their bodies than their British equivalents. The babies may have looked thin but their body composition was actually fat.6