Полная версия

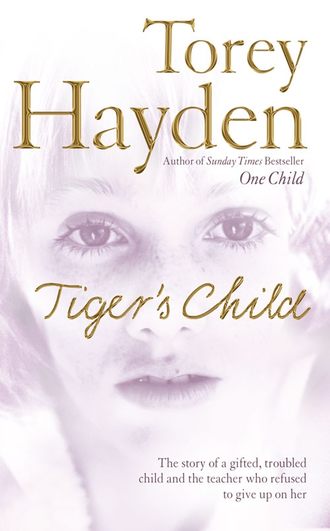

The Tiger’s Child: The story of a gifted, troubled child and the teacher who refused to give up on her

There was something compelling about sharing a book with Sheila. We would snuggle up together in the reading corner as I prepared to read aloud to her and Sheila would be so ravenous for the experiences the book held that her entire body’d grow taut with excitement. Winnie the Pooh, Long John Silver and Peter Pan proved sturdier magic than Chattel of Love. However, of all the books, it was Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince that won Sheila’s heart. She adored this bemused, perplexing little character. His otherness she understood perfectly. Mature one moment, immature the next, profound, then petty, and always, always the outsider, the little prince spoke deeply to Sheila. We read the book so many times that she could quote long passages by heart.

When not reading, we simply talked. Sheila would lean on the table and watch me work, or we would pause at some point in a book for me to explain a concept and the conversation would go from there, never quite returning to the story at hand.

Progressively, I learned more about Sheila’s life in the migrant camp, about her father and his lady friends who often came back to the house with him late at night. Sheila told me how she hid his bottles of beer behind the sofa to keep him from drinking too much, and how she got up to put out his cigarettes after he had fallen asleep. I came to hear more about her mother, her brother and the abandonment. And I heard about Sheila’s other school and her other teachers, about what she did to fill her days and her nights, when she wasn’t with us. In return, I gave her my world and the hope that it could be hers as well.

Those two hours were a godsend. All her short life Sheila had been ignored, neglected and often openly rejected. She had little experience with mature, loving adults and stable environments, and now, discovering their existence, she was greedy for them. The busy atmosphere of the classroom during the day, supportive as it was, did not allow for the amount of undivided attention Sheila required to make up for all she had lacked. It was in the gentle silence of the afternoon when we were alone, that she dared to leave behind her old behaviors and try some of mine.

Chapter 2

The real issue for Sheila was what had happened between her and her mother on that dark highway two years earlier. Given her extraordinary giftedness, the matter did not remain inarticulate. With exquisite clarity, she gave a voice to her agony.

The relationship between the abandonment and Sheila’s difficult behavior became most obvious over schoolwork. Despite her brilliance, Sheila simply refused to do any written papers. I hadn’t made the connection initially. I saw the aggressive misbehavior as waywardness and only afterward realized it was a ploy to keep her from having to sit down at the table and take a pencil in hand. Coercing her to the table proved a major battle and even then she held out, refusing to work. When she did eventually start accepting paperwork, she would still crumple two or three imperfect efforts before finally finishing one.

On one occasion, she wasn’t even in class but alone after school with me. She had found a ditto master of a fifth-grade math test in the office trash can, when she had come down with me while I ran off some papers. Sheila loved math. It was her best subject and she fell upon this with great glee. It was on the multiplication and division of fractions, subjects I had never taught Sheila, but as she scanned the paper, she felt certain she could do them. Back in the classroom, she settled across the table from me and began to write the answers on the paper—a very unusual response for Sheila. When she finished, she proudly showed it to me and asked if she had done them right. The multiplication problems were done correctly, but unfortunately she had not inverted the fractions for the division, so those were all wrong. Turning the paper over, I drew a circle and divided it into parts to illustrate why it was necessary to invert. Before I had even spoken, Sheila perceived that her answers weren’t right. She whipped up the paper from under my pencil, smashed it into a tiny ball and pounded on the table before flopping down, head in her arms.

“You didn’t know, sweetheart. No one’s taught you this.”

“I wanted to show you I could do them without help.”

“Sheil, it’s nothing to get upset about. You did nicely. You tried. That’s the important part. Next time you’ll get them right.”

Nothing I said comforted her and she sat for a few moments with her hands over her face. Then slowly her hands slid away and she uncrumpled the paper, pressing it smooth on the tabletop. “I bet if I could have done math problems good, my mama, she wouldn’t leave me on no highway, like she done. If I could have done fifth-grade math problems, she’d be proud of me.”

“I don’t think math problems have anything to do with it, Sheila.”

“She left because she don’t love me no more. You don’t go leaving kids you love on the highway, like she done me. And I cut my leg, see?” For the hundredth time the small white scar was displayed. “If I’d been a gooder girl, she wouldn’t have done that.”

“Sheil, we just don’t know what happened, but I suspect your mama had her own problems to straighten out.”

“But she copeded with Jimmie. How come she copeded with Jimmie and left me?”

“I don’t know, love.”

Sheila looked across the table to me, that haunted, hurt expression in her eyes. “Why did it happen, Torey? Why did she tooked him and leaved me behind? What made me such a bad girl?” Her eyes filled with tears, but as always, they never fell.

“Oh, lovey, it wasn’t you. Believe me. It wasn’t your fault. She didn’t leave you because you were bad. She just had too many of her own problems. It wasn’t your fault.”

“My pa, he says so. He says if I be a gooder girl she’d a never done that.”

My heart sank. There was so much to fight, so little to fight with.

The issue colored everything: her work, her behavior, her attitude toward other children and toward adults. As the weeks passed and particularly as we spent so much of the after-school hours in close contact, I knew very well what was being encouraged to happen. I was the first stable, nurturing adult female Sheila had occasion to spend much time with and she grasped at the relationship with greedy desperation.

Was it right to let her? This question was never far from my mind. My training, both in education and in psychology, cautioned rigorously against getting too personally involved with children, and I strove to keep the proper balance. On the other hand, I had always rebelled against the idea of not becoming involved at all. The cornerstone of my personal philosophy was commitment. I felt it was the unequivocal commitment of one individual to another, of me to the child I was working with, that evoked positive change. How could there be genuine commitment without involvement? That was a contradiction in terms.

On a gut level I felt Sheila had to have this relationship and without it she could never go forward. She needed the esteem that comes only from knowing others care for you, others value you sufficiently to commit themselves to you. She needed to know that while her mother might not have been able to provide this kind of commitment, this did not mean that Sheila was unworthy of it. Yet on an intellectual level I knew I was treading a dangerous path.

Just how dangerous came home to me in February, after Sheila had been with us about seven weeks. I had to attend an out-of-state conference, which meant I would be gone from class for two days. Having ample warning, I endeavored to prepare my class for my absence and the anticipated substitute teacher. Sheila reacted with rage.

“I ain’t never, never gonna like you again! I ain’t never gonna do anything you ask. It ain’t fair you go leave me! You ain’t supposed to do that, don’t you know? That be what my mama done and that ain’t a good thing to do to little kids. They put you in jail for leaving little kids. My pa, he says.”

Tirade after tirade and nothing I said, no effort I made to explain I would be gone only for two days abated Sheila’s anger. In my absence she reverted to all the worst of her old behaviors. She fought with the other children, bloodying noses and cracking shins. The record player was destroyed and the small window in the door was cracked. Despite Anton’s efforts to keep her in check, Sheila devastated the classroom and the substitute ended her days in tears.

I had expected better from Sheila and my anger, when she proved so uncooperative, was not a whole lot less than hers. She was a bright girl. She knew how long two days were. And I had gone to strenuous efforts to explain where I’d be, what I’d be doing and when precisely I would be back. She knew. Why could I not trust her to keep herself together for two lousy days?

To be more exact about the matter, I felt betrayed. Having known I was following such a dangerous course in allowing her growing dependence on me, I had wanted straightforward evidence that I was doing the right thing, that her dependence was natural and healthy and not too serious. I was, after all, going to have to walk out of her life in, at most, three and a half months’ time, when the school year ended, and in even less time, if the opening in the children’s unit at the state hospital occurred. For my own peace of mind, I needed reassurance I was helping more than hurting and—I suppose if I’m honest—I expected it from her. I had given her so much that, in my heart of hearts, I had trusted her to give this bit back to me. When she hadn’t, I reacted with an anger I didn’t control at all well.

We had, to put it mildly, a bad day, and even after school, when we were alone, the strained silence remained between us. I offered to do the things we’d come to enjoy so much: to read aloud to her, to let her help me correct my papers, to come down with me to the teachers’ lounge and share a soft drink, but she simply shook her head and busied herself in the far corner of the room with some toy cars. The first after-school hour passed. She rose and went to look out the window. When I next glanced up, she was still there but had turned to watch me.

“How come you come back?” she asked softly.

“I just went away to give a speech. I never intended to stay away. This is my job, here with you kids.”

“But how come you come back?”

“Because I said I would. I like it here. I belong here.”

Slowly, she approached the table where I was working. Her guard had dropped. The hurt was so clear in her eyes.

“You didn’t believe I was coming back, did you?”

She shook her head. “No.”

Chapter 3

Our falling-out over my absence did not appear to have any lasting effects. Indeed, just the opposite. Sheila developed an intense desire to discuss the incident: I had left her; I had come back. She had gotten angry and destructive; I had gotten angry and, in my own way, destructive. Each small segment she wanted to discuss again and again until it slowly slotted into place for her. The fact that I had come back was, of course, very important to her, but so too was the degree of my anger. Perhaps she felt that now that she had seen me at my worst, she could more fully trust me. I don’t know. Intriguingly, Sheila’s destructiveness virtually disappeared after this incident. She still became angry with great regularity, but never again did she fly into one of her rampaging rages.

Sheila bloomed, like the daffodils, in spite of the harsh winter. Within the limits of her situation, she was now quite clean and, better, she recognized what clean was and endeavored to correct unacceptable levels of dirtiness herself. Increasingly, she interacted with the other children in the class in a friendly and appropriate manner. She had gone home to play with one of the other little girls in the class on a few occasions and they indulged in the usual rituals of little girls’ friendships at school. Academically, Sheila sailed ahead, excited by almost anything I put in front of her. We were still coping with her fear of committing her work to paper, but that too improved through March. It seldom took more than two or three tries before she felt secure enough with what she had written down to let me look at it. She was still extremely sensitive to correction, going off into great sulks, no matter how gently I pointed out a mistake; and on moody days, she could spend much of the time with her head buried in her arms in dismal despair, but we were coping.

It was after school and Sheila and I had returned to The Little Prince yet again. Snuggled down in the pillows of the reading corner together, we had just begun the book. I had come to the part where the little prince demands that the author draw him a sheep.

“A sheep—if it eats bushes, does it eat flowers too?”

“A sheep,” I answered, “eats anything in its reach.”

“Even flowers that have thorns?”

“Yes, even flowers that have thorns.”

“The thorns—what use are they …?”

The prince never let go of a question, once he had asked it. As for me, I was upset over the bolt. And I answered with the first thing that came into my head:

“The thorns are of no use at all. Flowers have thorns just for spite!”

“Oh!”

There was a moment of complete silence. Then the little prince flashed back at me with a kind of resentfulness:

“I don’t believe you! Flowers are weak creatures. They are naive—”

Sheila laid her hand across the page. “I want to ask you something. What’s ‘naive’ mean?”

“It means someone whose ways are simple. They haven’t much experience with the world,” I replied.

“Do I be naive?” she asked, looking up.

“No, I wouldn’t say so. Not for your age.”

She looked back down at the book. “The flower thinks she has experience.”

I nodded.

“But the prince knows she doesn’t.” She smiled. “I do love this part. I love the flower.”

We read on:

So, too, she began very quickly to torment him with her vanity—which was, if truth be known, a little difficult to deal with. One day, for instance, when she was speaking of her four thorns, she said to the little prince:

“Let the tigers come with their claws!”

“There are no tigers on my planet,” the little prince objected. “And anyway, tigers do not eat weeds.”

“I am not a weed,” the flower replied sweetly.

“Please excuse me …”

“I am not at all afraid of tigers—”

The door to the classroom opened and the secretary stuck her head around the door. “Sorry to interrupt, Torey, but there’s a telephone call for you in the office.”

Handing Sheila the book, I rose and went down to take it.

It was the call I was dreading. The director of special education was on the other end of the line: a vacancy had come up in the children’s unit at the state hospital. Sheila’s time in my classroom was over.

To say I was devastated diminishes the enormity of the emotions I felt at that news. Whatever her difficulties, Sheila in no way belonged in a mental hospital. Intelligent, creative, sensitive, perceptive, she belonged here with us and, eventually, back in a normal class in a regular school.

I moaned, I pleaded, eventually I raged. The director listened. We got on well, he and I. I had always counted him among my allies in the district, the sort of man I relied on as a mentor, and this, if anything, made his call harder to take.

“It was settled long before any of us got into it, Torey,” he said. “You know that. There’s nothing we can do.”

Pathetic little flower, I thought, so proud of her fierce thorns, and when the tigers really came, the thorns gave no protection at all.

I simply couldn’t let it happen without a fight. When she had arrived in January, she had presented as bleak a case as I had ever encountered, and if they’d come for her then, I might have accepted it. But now …? The very thought of a child of Sheila’s caliber ending up institutionalized at six froze me to my soul.

That evening when I was home, ostensibly watching television with my boyfriend, Chad, a plan formed in my mind. I had so much evidence of both Sheila’s intelligence and her progress that I wondered if there might be a chance of changing things. It would have to be approached in a formal, unequivocal manner to be taken seriously and it would have to be undertaken rapidly. I glanced over at Chad. He was a very new junior partner in a law firm downtown and was spending much of his time as a court-appointed lawyer to those who couldn’t afford their own legal advice. So he knew the ropes.

“Is there a legal way to contest what they want to do with Sheila?” I asked cautiously.

“You fight it?” he replied, sensing the meaning under my words.

“Someone has to. I’m quite sure the school district would support me. The school psychologist has been in to administer IQ tests. He had evidence of her giftedness. And Ed knows.”

A pause. A few mutterings. I was the sort of person inclined, as Chad described it, “to get the bit between my teeth and run,” so I think he could guess the obsessive nature of what was going to happen.

“Would you take it on for me?” I asked.

“Me?”

Yeah, him.

And so it was. With admirable solidarity, the school district did back me fully. They even paid for Chad’s services. I marshaled together the videotapes I’d made of Sheila in class, her schoolwork, the psychologist’s evaluations and whatever other examples I could find to support Sheila’s steady improvement. The weakest link in the chain was Sheila’s father, who had been in and out of so many institutions himself that he didn’t seem to believe there was any point to pursuing a different life for his daughter. He was deeply suspicious of us because we did. Beneath his boorish behavior, I felt he did genuinely love Sheila, but it took several rather beery evenings between us to convince him we were right.

The hearing was held on the very last day of March, a dark, windy day that promised to bend the daffodils down yet again with snow. Sheila had had to come along, still dressed in her T-shirt and now badly outgrown overalls. They were clean and I had managed to get her father to accept socks and mittens for her from our church donation box, but that was the best I could do. She sat outside the courtroom with an attendant, in case we needed to call her in.

Inside, I saw the parents of the little boy whom Sheila had abducted and set alight. It was the first time I’d encountered them. Up to that moment, the incident that had placed her in my class had seemed distant to me. In truth, I suppose I had kept it distant in my mind in an effort to make such an act of calculated cruelty unreal. Sheila certainly had done some outrageous things and she had done plenty of them in my presence, so I’d always felt I had a realistic picture of her, but for the first time I had to confront the veracity of another point of view. This upset me, if for no other reason than that I had so desperately wanted to feel a hundred percent right in what I was doing just then. In a way I still did. Revenge would not undo the harm done to their son and it would cripple Sheila for life. This was the only right route for this girl. Yet the hearing brought home to me the enormity of what she had done.

The judge ruled in Sheila’s favor. She was to remain under Social Services supervision, but the order for detainment in the children’s unit was rescinded. Joy broke out in the halls of the courthouse, and afterward, Chad and I took Sheila out to celebrate.

It was a magical evening, one of those times when the experience is greater than the sum of its parts. Still high from our success, we went for pizza in a place Chad and I haunted frequently, full of smoke and jazz music and people speaking Italian. Sheila had never had pizza and took to the new experience with animated delight. Indeed, she took to Chad, and he, likewise, to her. He was soon as much under her spell as I was.

They got into a silly contest, the two of them. What would you like best? To eat a worm sundae or brush your teeth with a spider toothbrush? That sort of thing. Until Chad went serious and asked what was the thing she would like best in all the world—for real. A dress, as it turned out. Something pretty to wear. Unable to resist this opportunity to play Santa Claus, Chad soon had us out to the shopping center. Despite all Sheila’s fears that her father wouldn’t let her accept a dress, Chad reassured her and helped her find the one she liked best.

Sheila fell asleep on the way back to her house in the migrant camp.

“Well, Cinderella,” Chad said, coming around to my side of the car and opening the door. He reached down and lifted her up. “The ball’s over.”

She smiled sleepily at him.

“Come on. I’ll carry you in and tell your daddy what we’ve been up to.”

She buried her face in my hair. “I don’t wanna go,” she whispered.

“It’s been a nice night, hasn’t it?” I said.

She nodded and she pressed tighter against me. “Can I kiss you?”

“Yes, I think so,” I said and enveloped her in a tight hug and kissed her first.

Chapter 4

My class would cease to exist at the end of that school year. The mainstreaming law with its edict that every handicapped child should be placed in the least restrictive alternative was the primary cause. Most of the special education classes were being closed and teachers like myself were being redeployed as “resource people” to provide support to the regular classroom teachers, who would now have special education children among their students.

I wasn’t terribly comfortable with this change. While I would have liked to accept the law on the ideological grounds it was being put forth on—that it would promote greater equality and opportunity for handicapped children—I was too much of a natural cynic. The far more obvious factor to me was that it was a cheaper way to educate handicapped children.

On a personal level, my style of teaching was best suited to the closed environment of a self-contained classroom. It was in this setting I was at my best. I could create the tight-knit, supportive milieu that became my trademark and it was under these circumstances I could encourage the most positive growth among my students. Consequently, I was loath to become a floating resource person with my children reduced to a catalog of educational problems I was given twenty minutes a week to sort out. Most difficult, however, was being boxed in theoretically. I was an eclectic, picking and choosing my methods of operation from a wide variety of sources, some of them entirely outside education. This seemed the only sensible approach when dealing with such varied difficulties as one comes across in human behavior. However, with the new law we were going to be restricted, generally to some form of behavior modification. I was competent enough with this approach but felt it vastly overrated as a method and rather dangerous as a theory. Thus, not feeling that I was ready to commit myself to all of this, I applied and was accepted at an out-of-state university to do further graduate work.

It was May and school would end the first week in June. In the four and a half months Sheila had been with us, she had metamorphosed into a lively, sunny-natured girl. We had had no serious breaches of behavior since that week in February when I had gone to the conference, and while she was still capable of a hearty tantrum when provoked, normal methods of discipline brought her back into line. She could now express anger without destructiveness; she could be reasoned with; and she could even accept a small amount of gentle criticism without falling to pieces. In short, I didn’t feel Sheila would need a special class any longer. She was still fragile and the placement would need to be well thought out, but I was convinced she had the capacity to get on in a normal classroom.