Полная версия

The Secret War: Spies, Codes and Guerrillas 1939–1945

The British breaking of the Enigma, then subsequently and separately of German teleprinter traffic, was a progressive, incremental operation which attained maturity only between 1943 and 1945, and was never uninterrupted or comprehensive: even at peaks, only about half of all intercepts were read, many of them too late to provide practical assistance ‘at the sharp end’. What was done at Bletchley Park was indeed miraculous, but the codebreakers were never able to walk on all of the water, all of the time.

The 1939–40 Phoney War conferred few benefits on Britain, but it granted GC&CS precious time to bolster its strength and refine its methods. Without mechanical aids Bletchley’s brainstormers made modest and delayed breaches in a small number of enemy ciphers. The Germans employed acronyms and codenames which took weeks or months for their enemies to interpret. The importance of what happened at Bletchley in the first two years of war was not that it enabled Britain’s generals to avert or arrest a disastrous run of defeats, which it certainly did not, but that it lit a candle of hope about what the codebreakers and their embryo technology might accomplish in the future. It enabled the directors of the war effort to lay upon the board a few scattered pieces of a vast jigsaw, which would be filled only during the Allies’ years of victory.

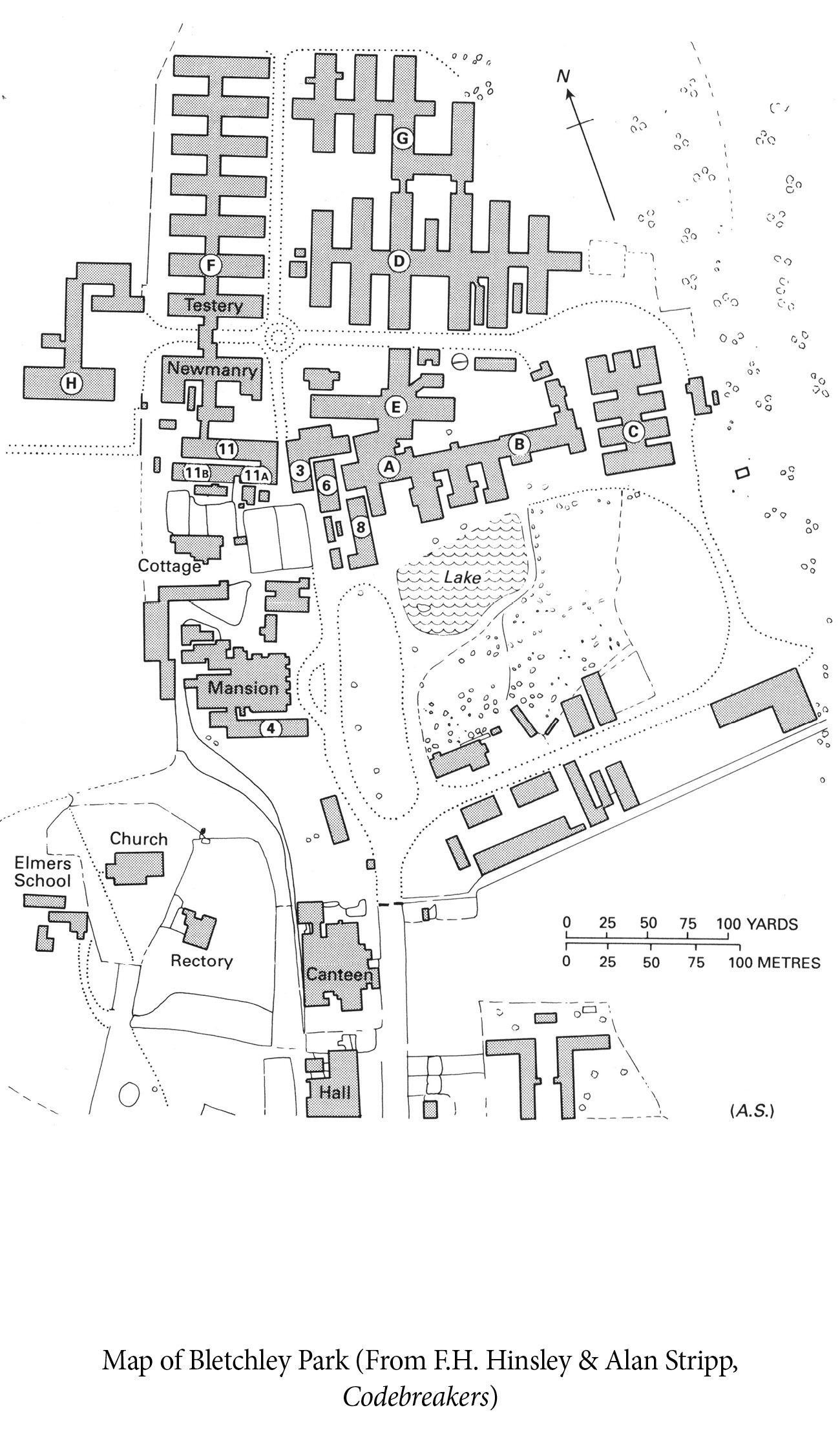

Bletchley Park – Station X, Box 111 c/o The Foreign Office – was a notably ugly Victorian pile of bastard architectural origins surrounded by fifty-five acres of trees and grassland, located fifty miles from London. It was purchased in 1938 to house GC&CS at a safe distance from German bombs by Admiral Sir Hugh Sinclair, then head of MI6; as legend has it, he used £7,500 out of his own pocket, but more plausibly he paid with secret funds under his control. Whatever MI6’s humint weaknesses, the service’s chiefs, especially Sinclair, deserve full credit for backing the establishment of Bletchley at a time when resources were desperately constrained. Work began at once on laying direct phone and teleprinter lines to London, and in the following year MI6’s skeleton team of cryptanalysts moved from Broadway to the Park, where they came under the orders of Alastair Denniston. One of his colleagues from the old Admiralty days, Dillwyn Knox, an expert on ancient Egyptian papyri, became an early Bletchley stalwart. The most prominent of the younger recruits were Gordon Welchman of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, Hugh Alexander, Stuart Milner-Barry, John Jeffreys – and Alan Turing.

This last, the twenty-seven-year-old son of an Indian civil servant and the product of an austere and emotionally arid childhood, had just returned from a stint at Princeton clutching one of his own creations, a so-called electric multiplier machine mounted on a breadboard. His headmaster at Sherborne had once written: ‘If he is to stay at a public school, he must aim at becoming educated. If he is to be solely a Scientific Specialist, then he is wasting his time.’ In the headmaster’s terms, Turing had indeed been ‘wasting his time’: he had evolved into a shy, narrow, obsessive. Noel Annan wrote: ‘I liked his sly, secret humour … His inner life was more real to him than actuality. He disliked authority wherever he was … [and] enjoyed games and treasure hunts and silliness … Turing was the purest type of homosexual, longing for affection and love that lasted.’ More even than by his sexuality and his often childlike immaturity, however, his tragedy was to be afflicted by the exquisitely painful loneliness of genius.

Other drafts of young academics followed, variously codebreakers and linguists, together with the first of what became successive waves of young women, who would play a vital role in the operations of ‘BP’. The first two of these were daughters of golfing partners of Denniston, reflecting the importance of personal connections in Bletchley’s recruitment process in the early days, before industrialisation became inescapable. Indeed, the whole wartime intelligence machine emphasised the cosiness of the upper reaches of British life. Oxford University Press was entrusted with responsibility for printing vast quantities of codes, maps and reports, because of its pre-war experience producing examination papers under secure conditions. The Admiralty’s liaison with OUP was handled by Margaret Godfrey, wife of the director of naval intelligence. The Royal Navy’s Topographical Photographic Library was housed in the basement of the nearby Bodleian Library, which eventually dispatched 300,000 images a month to operational areas. The World War I intelligence veteran Admiral Sir William ‘Blinker’ Hall introduced Godfrey, his modern successor, to the City of London banking giants Montagu Norman, Olaf Hambro and the Rothschilds, who helped to identify suitable recruits for the NID.

Candidates being scrutinised for Bletchley were often asked: ‘Do you have religious scruples about reading other people’s correspondence?’ Twenty-year-old Harry Hinsley was interviewed at St John’s College, Cambridge by Alastair Denniston and Col. John Tiltman, the senior codebreaker. They said: ‘You’ve travelled a bit, we understand. You’ve done quite well in your Tripos. What do you think of government service? Would you rather have that than be conscripted?’ Hinsley would indeed, and joined the Naval Section located in Bletchley’s Hut 4. Through the icy winter of 1939–40, such men and women wrestled with Enigma traffic. Working conditions were dismal, with staff muffled in overcoats and mittens. The first break into a Luftwaffe Enigma key – designated ‘Green’ – is thought to have been made on 25 October 1939. In December, by unaided intellectual effort Alan Turing is believed to have broken five days’ worth of old naval messages. By the end of March, the French – or rather, the Poles working at France’s Station Bruno – had broken twenty days’ worth of old signals and BP about thirty, all Luftwaffe traffic.

Turing was much more importantly engaged. He compiled a 150-page treatise on Enigma, studded with schoolboyish blots, deletions and illegibilities. While most codebreakers addressed each other by first names or nicknames, heedless of age and status, almost everyone knew Turing as ‘Prof’ rather than as Alan. When his Enigma study was circulated later in 1940, it became known as ‘the Prof’s book’. He also set about fulfilling his concept for a ‘bombe’, a primitive but revolutionary electro-mechanical device for exploring multiple mathematical combinations. This borrowed its name, though not its design, from the Polish ‘bomby’, and would be capable of examining the 17,576 possible wheel deployments for a three-rotor Enigma in about twenty minutes: the order for the first machine was placed in October 1939, and the prototype became operational six months later. Meanwhile, outside in the park, workmen sawed and hammered at an ever-widening array of low wooden buildings which housed the growing staff. Eventually, only administrators worked in the main building, where the telephone switchboard was established in the ballroom. In the huts, signals were shifted from one section to another on a small trolley pushed along a makeshift wooden tunnel.

Hut 8 attacked German naval traffic, which was then passed to Hut 4 for translation and processing. Hut 3 performed the same function for Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe traffic decrypted by Hut 6. The former would eventually play a pivotal role in Allied wartime intelligence, but in its early incarnation it had a staff of just four. Frank Lucas, who was one of them, wrote: ‘On a snowy January morning of 1940, in a small bleak wooden room with nothing but a table and three chairs, the first bundle of Enigma decodes appeared. [We] had no idea what they were about to disclose.’ A few score yards away, Hut 6 run by Gordon Welchman wrestled with army-Luftwaffe ‘Red’ key traffic, which was the first to be broken in bulk.

From the outset, pains were taken to disguise from all but the most senior operational commanders the fact that information was being gained from codebreaking. This gave an unintended boost to the prestige of MI6, and to that of Stewart Menzies in particular. When Reg Jones gave a disguised report based on an Ultra decrypt to the RAF’s director of signals, Air Commodore Nutting, the airman professed astonished admiration for the courage of the presumed spies who had provided the information, saying, ‘By Jove, you’ve got some brave chaps working for you!’ The ever-growing scale of the enemy traffic to be trawled was intimidating. It is a measure of the expansion of communications as a branch of warfare that by August 1943, 305,000 personnel among the Luftwaffe’s total strength of 2.3 million were employed on signals duties – transmitting, receiving or processing – and the same was true on both sides of the war, and of all armed forces.

At GC&CS there were inevitable personality clashes. Gordon Welchman, whose creative contribution became second only to that of Turing, and whose organisational skills were also priceless, found it hard to work with the highly-strung and fractious Dillwyn Knox, a contender for the hotly contested title of Bletchley’s star eccentric. A notoriously awful driver, Knox giggled: ‘It’s amazing how people smile, and apologise to you, when you knock them over.’ He sustained a stream of intemperate complaints and demands to Denniston, his old comrade from Room 40, about staff shortages, working conditions, low pay, together with the intrusion of and excessive authority conceded to non-cryptanalysts: service intelligence officers ‘who maul and conceal our results’. Knox was seriously ill with the cancer that would kill him in February 1943, but meanwhile he and Welchman bickered: the older man accused the younger of exceeding his narrow initial brief, and was also impatient of Turing, writing, ‘He is very difficult to anchor down. He is very clever but quite irresponsible and throws out a mass of suggestions of all degrees of merit. I have just, but only just, enough authority and ability to keep him and his ideas in some sort of order and discipline. But he is very nice about it all.’ Turing prompted mirth by joining Bletchley’s Home Guard because he was seized by an impulse to learn to shoot, then provoked the apoplectic rage of its colonel by absenting himself from parades once he had fulfilled this private purpose. His unworldliness could provoke real exasperation among those under relentless pressure to produce results. A colleague spoke of Turing’s ‘almost total inability to make himself understood’.

There were plenty of minor tantrums lower down the hierarchy, unsurprising when staff were performing stressful tasks through long hours in bleak working conditions. Angus Wilson, the later novelist, once vented such a storm of rage that a colleague said wearily, ‘Do stop it, Angus, otherwise we’ll put you in the lake!’ Wilson retorted defiantly, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll do it myself,’ and duly plunged into the water in front of the house; on another such occasion he hurled a bottle of ink at a Wren. Many wartime codebreakers suffered temporary or permanent physical or mental collapses, brought on by their work: William Friedman, one of America’s pioneer practitioners, underwent a nervous breakdown in January 1941 which incapacitated him for three months. Hugh Trevor-Roper languished for several months at about the same time, and others regularly succumbed.

German signals were at first intercepted by a battery of army wireless-operators stationed in an old naval fort at Chatham, a role later assumed by Gambier-Parry’s organisation at Whaddon Hall. In the early war years there were never enough operators, and both the RAF and the army were reluctant to acknowledge the priority of meeting GC&CS’s demands. Signals were brought in batches to Bletchley’s guardroom by motorcycle couriers, at all hours and often in dreadful weather, then distributed between the relevant huts. From an early stage, the codebreakers learned to identify German senders by the unencrypted preamble to their message texts, none of which was longer than 250 words. It was then a matter of sitting hunched over a deal table through the hours of a shift, pondering a jumble of numbers and letters from which only men – and Bletchley’s handful of women – with remarkable logical or mathematical powers might hope to extract fragments of meaning. ‘The ideal cryptanalyst,’ Stephen Budiansky has written, ‘was Beethoven with the soul of an accountant.’ When Christopher Morris was a new recruit to Bletchley he heard one of his senior colleagues, asked the requirements for the job, respond laconically, ‘Oh, I suppose a sharp pencil and a piece of squared paper.’ Morris himself thought that the main requisites – except at the exalted level of Knox, Turing, Welchman and later Max Newman – were ‘patience, accuracy, stamina, a reasonably clear head, some experience and an ability to work with others’.

They opened what became vast card indexes, stacked in shoeboxes along the sides of the huts, cataloguing enemy units, personnel, codenames, locations, abbreviations and military hardware; different Enigma keys were distinguished by colour – for instance, yellow, green, red and blue, respectively indicating Norway, Wehrmacht, army-Luftwaffe and air training codes. ‘When a new word came up in the message you were translating,’ wrote Hugh Skillen, ‘a new type of jet fuel, or machine part – you looked for it, and if it was not there, the indexer put it in with a reference time and date stamp.’ Bletchley’s meticulous record-keeping became a critical element in its triumphs.

For security reasons, the Park’s operations were rigidly compartmentalised, and there was little exchange of information or gossip between sections. Even Welchman remarked years later how little he knew about what colleagues were doing a few yards away from his own Hut. As the staff grew from hundreds into thousands, facilities lagged behind: a section head complained that two hundred men and women enjoyed the use of just one lavatory. The food in the Bletchley canteen was poor even by wartime standards. Former debutante Sarah Norton one night found a cooked cockroach in her meat: ‘I was about to return it to the catering manageress when my friend Osla, who had the appetite of a lioness with cubs, snatched the plate and said: “What a waste – I’ll eat it!”’ The nearest available delicacies outside the wire were to be found at the Station Inn in Bletchley town, which offered ox heart. Welchman recalled having to provide his own newspaper to wrap fish and chips at the local shop. The codebreakers worked around the clock in three rotating shifts, starting with 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. When the exhausted men and women cycled or took a bus through the blackout to their lodgings, they found few comforts: dim lighting, hot baths often rationed to one a week, draconian rules about inter-sex visiting.

It is deeply impressive that those who worked at Bletchley sustained such dedication while working day after day, month after month, in a drab world devoid of glamour, excitement, variety, glory and decorations. In Hut 3, the watch sat around a horseshoe table, translating deciphered signals, each one resembling a telegraph flimsy, forwarded from Hut 6. Ideally, decrypts were composed of complete German words, but often there were interruptions and corruptions in the texts, which demanded leaps of imagination from the linguists. William Millward recalled with shame a night when he invented a place named ‘Senke’, near Qatara in the North African desert – having forgotten that Senke was the German word for a geographical depression. Schoolmasters proved ideal as watch chiefs, wrote Peter Calvocoressi, because they were naturally meticulous: ‘If not satisfied, they would throw back a translation at even an eminent professor. It reminded me of Chief Examiners at “A” Level who would send back scripts to an Assistant Examiner to re-mark.’ No one could work at GC&CS who did not love brain games. There were dreary, idle yet sleepless lulls, when no traffic arrived for the watches to work on. Peter Hilton once used such a doodle time to compose a palindrome: ‘DOC NOTE, I DISSENT, A FAST NEVER PREVENTS A FATNESS. I DIET ON COD’.

Although Alan Turing was acknowledged as the highest intellect at Bletchley, its achievement was supremely a team effort; the creative input of some others, Welchman prominent among them, was almost as important as that of Turing. One night in February 1940, several months before the arrival of the first bombe, twenty-one-year-old Cambridge mathematician John Herivel was smoking a pipe before the fire in his billet, and concentrating furiously on encoded messages even as he drifted in and out of a doze. An inspiration struck him as he gazed with the mind’s eye at a German Enigma operator. He perceived such a man starting his morning’s work bored or weary or hungover, and thus not troubling to change the previous day’s ring setting on his machine before starting to cipher messages. Herivel scarcely slept that night, as he went on to deduce how such an act of carelessness might be detected, then exploited to break a message.

Welchman, who had supervised him at Cambridge, immediately saw the importance of this flash of insight, a marriage of mathematical brilliance to a grasp of human weakness. He told the young man fervently that he ‘would not be forgotten’, and indeed his inspiration became known as ‘the Herivel tip’. Dillwyn Knox had already identified another entry point to messages, rooted in operator errors and text settings – what the codebreakers christened ‘Cillis’ or ‘Sillies’. Welchman wrote later that Bletchley remained ‘entirely dependent on Herivel tips and Cillis from the invasion of France to the end of the Battle of Britain’. In other words, until the arrival of the bombes, codebreaking was being done by raw brainpower, without significant mechanical assistance: at this early stage, the British lagged behind their American counterparts in exploiting technology – both the US Army and US Navy codebreaking teams used Hollerith punched-card sorters, of a kind that only began to appear at Bletchley in May 1940, because chief codebreaker Col. John Tiltman had been sceptical about them. Ultra provided no important material during the summer of 1940, but several indications about the postponement of ‘Sealion’, the Nazi invasion of Britain, notable among them a September Luftwaffe message ordering the dismantling of air transport equipment at Dutch airfields.

Fred Winterbotham, the MI6 officer who eventually became overseer of the ‘Special Liaison Unit’ network which fed Ultra decrypts to commanders in the field, described the first bombe – christened ‘Agnus’, corrupted to ‘Agnes’ – as resembling ‘some Eastern goddess who was destined to become the oracle of Bletchley’. It was installed in Hut 11 on 14 March 1940, but suffered substantial teething troubles. Gordon Welchman made an important contribution to Turing’s creation by devising a ‘diagonal board’, an element introduced into the first really effective model, which came into service in mid-August. Agnes and its many successors were not computers, because they had no memory. They were instead electro-mechanical key-finding aids, six and a half feet high and seven wide, mounted in bronze-coloured cabinets, and containing thirty-six banks of high-speed electrically-driven Enigma replicas. Each bombe contained eleven miles of wiring and a million soldered contacts. Built by the British Tabulating Machine Company at Letchworth, they depended partly on components assembled in scores of local village halls, by casual workers who had no clue of the importance to the war effort of the twenty-six-way cables and other small electrical parts they contributed.

With the assistance of a clue or ‘crib’ – a vital identifying link, usually a codebreaker’s guess about the nature of part of a given signal – a bombe could test millions of mathematical possibilities for the settings of three Enigma rotors. Figuratively, Agnes and her kin were bloodhounds needing a slipper or handkerchief to take up a scent. If there was no ‘crib’, the bombe could not solve the key – but mercifully often, there was one. Subsequent machines, miracles of reliability given their continuous operation, were given their own names by the Wrens who manned them around the clock, usually those of warships – Warspite, Victory and suchlike. The bombes did not take in enemy cipher messages and disgorge them in fluent German. They were instead priceless accelerators, once the codebreakers secured an insight into the nature of a given signal or traffic stream. Also useful was a battery of British Type-X cipher machines, modified to match the behaviour of Enigmas, on which Wren operators tested speculative message solutions. One of the principal constraints on codebreaking, especially between 1940 and 1942, was that access to the scarce technology had to be apportioned between competing claimants of the three services, and there was never enough ‘bombe time’ to go around.

Throughout 1940, human brainpower remained the dominant element in Bletchley’s successes, which increased with every passing week. It was ‘the Herivel tip’, not bombes, that enabled the team to crack the army-Luftwaffe ‘Red’ key in May. The overwhelming bulk of enemy traffic read through the rest of the year – around a thousand messages a day – was that of the Luftwaffe, and until the end of the war air force material was accessed more swiftly than that of the other services. An important requirement for success was what the codebreakers called ‘depth’ – possession of sufficient messages in a given key to give them playing space for calculations and speculations.

Luftwaffe signals provided many clues to the Wehrmacht’s parallel activities, but in the early days interpretation was impeded by lack of understanding of German terminology and abbreviations. In September 1940, Bletchley broke some traffic from Göring’s pathfinder unit, KGr100, which enabled it to forecast the targets of several bomber raids. But warning was of little practical usefulness to the defenders when hard power, in the form of radar-guided RAF night-fighters, was lacking in both numbers and effectiveness.

As more bombes were built – by 1945 there were 211 of them – they were dispersed around the London suburbs as a precaution against an enemy air attack on Bletchley. The operators, chiefly young women of the WRNS, found long hours beside the hot, smelly, clattering machines extraordinarily gruelling, especially when they were obliged to use tweezers to adjust the delicate electrical wiring. Some girls were unnerved by the monotonous racket. One of them said: ‘It was like a lot of knitting machines working – a kind of tickety-clickety noise.’ They went home with their shirt cuffs blackened by a fine spray of oil from the bombes’ revolving drums.

Naval Enigma remained for many months impenetrable. This was partly because its system of eight rotors, of which three were used at any one time, posed greater difficulties than the army’s five, and partly also because the Kriegsmarine’s operators were more disciplined than their Luftwaffe counterparts, and committed fewer errors to provide openings for Bletchley. There was a brief spasm of success in late April 1940, when five days’ traffic was read, but thereafter more than a year elapsed – an eternity in the minds of those who wrestled vainly with the problem day after day, week upon week – before the big breakthrough. Denniston said gloomily to Frank Birch, a 1918 veteran of Room 40 who now headed the naval section: ‘You know, the Germans don’t mean you to read their stuff, and I don’t suppose you ever will.’ Alan Turing himself had been dallying with the Kriegsmarine’s traffic almost since his arrival at Bletchley. A colleague, Hugh Alexander, observed that he became engaged because nobody else seemed to be making headway, and in his remote fashion he was fascinated by the abstract challenge.

It was Turing who devised a new method christened ‘Banburismus’, employing long punched paper sheets manufactured in the town of Banbury, which assisted the first important breaks into Kriegsmarine messages by reducing the number of possible Enigma rotor orders to be tested from 336 to around eighteen. This system was introduced in the spring of 1941, just as British losses to U-boats began to become alarming. On land, the British in those days lacked power and opportunity to do much with such knowledge of the Wehrmacht’s movements as they secured, and there was a large element of luck about what messages were broken. In North Africa in early 1941, the British Army profited from some good sigint derived from eavesdropping on the Italians, but few Enigma messages were broken quickly enough to assist decision-making on the battlefield. At sea, by contrast, there was an early golden prize for GC&CS’s labours.