Полная версия

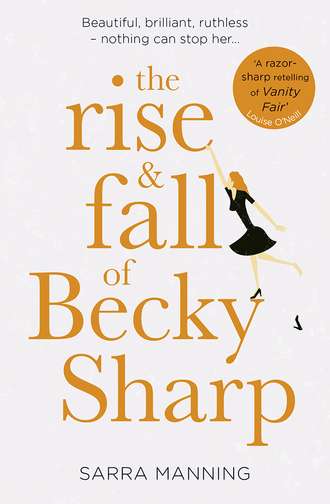

The Rise and Fall of Becky Sharp: ‘A razor-sharp retelling of Vanity Fair’ Louise O’Neill

‘Daddy and Jos always used to joke that it was because I had no backbone,’ she admitted with a nervous giggle. And of course there was the measly two weeks that Amelia had spent doing volunteer work in Niger.

‘Like Princess Diana,’ the journalist, Emily, noted dryly. ‘Were you worried about catching something awful like yellow fever or malaria?’

‘Not quite like Princess Diana. I mean, there were no landmines and we had WiFi,’ Amelia said. ‘But I did have to have a lot of jabs before I went. My arm was sore for days afterwards.’

On the other hand, Becky’s biography was quite sparse. It was also quite hard to remember what she’d told people in the Big Brother house. Another lesson learnt: come up with a story then stick to it as if your life depended on it.

‘My father was an artist,’ she recalled with a misty look to her eye, because to be fair, some of his scams really had possessed quite a lot of artistry. The judge who’d sent him down had described him as ‘a curious mixture of criminal genius and petty thief with poor impulse control.’ ‘Everyone said that he was destined for greatness but he died before greatness came.’

‘And, I understand how hard this must be for you, but how did he die?’

Becky cast her eyes down. ‘He had a brief but brave fight against a cruel disease.’ When she said that people always assumed that it was cancer and that she’d been at her father’s side as he was carried away by the angels. The ugly truth of the matter was that it had been cirrhosis of the liver and the only person at his side had been a prison chaplain, as Francis Henry Sharp had been serving seven years at Her Majesty’s Pleasure for five counts of fraud and one count of ABH for breaking the nose of the arresting officer.

Next to her, Amelia snivelled a little and the journalist leaned closer. ‘And your mother died when you were still quite young?’

Becky did her best brave face. Downcast eyes, a little half-smile, a sudden intake of breath as if she was fighting to control herself. ‘Yes, by the time I was eight, it was just Daddy and me. I’m sorry, can I have a moment?’

‘It’s very painful for Becky to talk about,’ Amelia whispered, taking hold of Becky’s hand as if she could loan her friend some of her own meagre courage. ‘Are you OK to carry on? Do you want some water?’

An intern was despatched to bring Becky water. Sparkling water in a cut-glass tumbler with crushed ice and a big chunk of lime.

Who could blame a girl for not wanting to go back to a life where there was only tap water in any receptacle that was vaguely clean?

‘Your mother?’ Emily prompted. ‘You said in the house that she was French.’

‘Mais oui, maman etait francaise. She came from a very old family, the Mortmerencys, and she was a model. No! You wouldn’t have heard of her. She did a little catwalk, but mostly fit work,’ Becky explained, though the closest her mother had come to the catwalk was draping herself over the bonnet of a Ford Fiesta at a motoring exhibition at Olympia. She had been quite pretty before the booze and the pills and the putting up with Frank Sharp had taken their toll on her. ‘Her passing was very sudden.’

Hurling yourself in front of the 7.08 District Line train pulling into Fulham Broadway station didn’t lend itself to a long, lingering death.

‘Oh, Becky,’ both Amelia and Emily exclaimed.

‘Sorry, it’s just that it’s painful to talk about.’

Had it been painful at the time? Becky could hardly remember. Sidonie had barely fulfilled her job description. She swung from high to low, as Mr Sharp had vacillated from sweet to mean, so from a very young age, Becky had learned to keep her head down, stay out of the line of fire, especially when her parents had fought, which they did with intense ferocity. If that was love, then you could shove it.

‘So, Becky, let’s switch it up, shall we?’ Emily asked.

Becky clapped her hands together. ‘God, yes, please, let’s!’

Where had she gone to school?

School of hard knocks.

Had she had many boyfriends?

Only if you count a Bournemouth vicar who used to try to put his hand up my skirt when I was helping with the church jumble sale.

Who were her celebrity crushes?

What would be the point of having a crush on some distant celebrity who would be of absolutely no use to me?

Dear, sweet Emily and her voice recorder would probably both short circuit if Becky told them a few home truths, so she settled for the current truth and put her arm around Amelia.

‘I’m just here for moral support. Emmy’s the star and so she’s the one you should be asking about boyfriends and crushes.’ Becky nudged Amelia who giggled obligingly.

‘There is someone,’ Emmy confided, because it never occurred to her that she could fudge the details, hint, or stretch, bend and pull the truth this way and that, so it hardly even resembled the truth any more. ‘I’ve known him all my life, he was at school with my brother Jos, so I’m sure he thinks I’m still the silly little girl that he always teased.’

Such a cliché. The haughty older boy who …

‘… used to pull my pigtails.’

Even Emily was starting to look as if her back teeth were aching from Amelia’s brand of simpering, saccharine sweetness.

‘And does this someone have a name?’ Emily asked with the weary air of a woman who had an Oxbridge degree and a childhood ambition to be a lady war correspondent, but was currently interviewing the winner (and runner-up!) of a reality TV show.

Amelia ducked her hair. ‘George,’ she said on a gasp, as if even saying his name out loud was tempting fate. ‘His name is George.’

Chapter 5

‘He’s very good looking,’ Becky whispered loudly to Amelia as they stood in the doorway of the Sedleys’ drawing room later that evening and she caught sight of the man sitting on an antique loveseat, his gaze fixed on his iPad. ‘You might have thought to mention it!’

Amelia frowned. ‘Really? Do you think so?’ The frown was replaced by a mischievous smile. ‘Shall I tell him?’

‘I’ll hate you for ever if you do,’ Becky said, noting the way the man began to stab frantically at his touch screen, as if he’d actually heard every word of their conversation.

It was no wonder that Jos Sedley – the object of Becky’s affection, Amelia’s own brother, and both the brains and the brawn behind A Load Of Balls, the second-largest protein-ball company on the West Coast (soon to make major inroads into the East Coast market too) – had caught Becky’s attention.

He truly was a sight to behold. A cross-fit addict who could bench press his own weight (two hundred and ten pounds) and a man who hadn’t knowingly eaten a carb in five years, Jos Sedley was triangular in shape. His over-muscled top half, bulging biceps, pecs even perter than Becky’s, strained the seams of his tight T-shirt, which was daringly low cut to show off his stunning he-vage. His spindly, skinny, jeans-clad legs didn’t look able to support all that complex musculature.

It took a while for Becky’s eye to take it all in and travel adoringly up Jos’s physique, past his thick neck to a face still resolutely fixed on his iPad screen. It wasn’t a distinguished face. If it weren’t for his extraordinary physique, it would be hard to pick Jos out in a police line-up. The only remarkable thing about it was that, like the rest of him, it was somewhere between teak and mahogany on the fake-tan colour spectrum.

‘Jos! Nothing on your iPad could be as interesting as my Becky,’ Amelia said and finally Jos looked up from where he’d been studying a new pull-up technique that his personal trainer had devised for him.

Becky had been gazing down at the Aubusson rug because it would have been rude to keep staring at Jos even though he really was a fascinating sight, but now she looked up too in time to see Jos blush fiercely as their eyes collided.

‘Any friend of Emmy’s and all that …’ He muttered awkwardly as he stood up, trying desperately to remember the most appropriate way to greet his sister’s friends. He’d spent his formative years in all-male boarding schools and he’d been a fat kid. A fat, shy kid. Even when there’d been dances with the neighbouring girls’ boarding schools, Jos had stayed on the sidelines, never daring to try and steal a kiss or cop a feel during the last dance. Since moving to LA after an equally unhappy three years at Keele University, Jos had turned his bulk from blubber to muscle but he was still shy. What’s more, he knew he was shy and awkward, so he was instantly suspicious of any woman who showed an interest in him.

Becky noted the blush, which highlighted Jos’s terracotta face. It seemed to Jos that she could see deep into his soul and evidently what she found wasn’t at all repulsive to her, because she stepped forward and suddenly threw her arms around him.

There was so much softness pressed against Jos that he hardly knew what to do with himself but all too soon, it was gone. Becky stepped back, hands to her own cheeks, as if she were blushing too, though her blush owed more to the Benefit cheek tint she’d taken from Amelia’s make-up bag that morning. The last thing that Amelia needed was blusher so really Becky had been doing her a favour.

‘I’m sorry,’ she apologised to Jos, who was staring at her like a cartoon character who’d just had an anvil dropped on his head. ‘I don’t know what came over me. I’m not normally a hugger, am I, Emmy?’

‘Becky’s mother died very young so she has cuddle deficiency syndrome,’ Amelia said, even though Becky had told her that in the strictest confidence in the Big Brother house as eighty cameras filmed their every move.

‘But as soon as I saw you, I wanted to hug you,’ Becky said, shrugging helplessly. ‘I’ve behaved like a total idiot, haven’t I?’

‘No, no! Not at all. I’m very honoured to have been, er, hugged. You’re a very good hugger. It was a good hug. Best hug I’ve had in a long time.’ Jos held up his hand in despair. ‘Hug. Never realised what a strange word it is before. Hug.’

‘A very strange word,’ Becky agreed. ‘But such a nice thing to do.’ She turned to Amelia who had her hands clasped to her chest, her mouth wide in wordless delight that the first meeting of her beloved brother and her BFF had gone far better than she could ever have hoped for. ‘Emmy, do you think you might hug Gorgeous George when you see him again?’

‘Gorgeous George? Hug him?’ Jos echoed. His massive chest shook with mirth at the idea. ‘I’d love to see his face if you did, Emmy.’

Jos’s laugh was infectious. Deep, braying and loud, like the mating cry of an amorous water buffalo. Becky couldn’t help but laugh at the sound of it. Amelia pouted but she could never stay angry for very long and also George would be very surprised if she did suddenly hug him, so she ended up giggling too.

When Amelia saw George Wylie later that night, it was true that she felt a strong impulse to hug him. But what she secretly wished was that George would be so overcome by the sight of her that he’d be the one to stride over and take her in his arms, kiss her on the forehead and murmur throatily, ‘I’ve missed you, Emmy. Missed you more than I can say.’

It wasn’t to be. Instead, George slightly inclined his head when Amelia waved frantically at him from across the room, then went back to talking to his friends.

‘He’ll probably come over in a bit,’ she said to Becky who had wanted Gorgeous George pointed out to her as soon as Amelia clapped eyes on him. ‘He looks quite busy.’

‘And then you’ll be too busy to talk to him,’ Becky said firmly, because although she was many things, most of them not at all good, in times of adversity she could be a great comfort. ‘After all, this is your party.’

The party was being thrown by Mr and Mrs Sedley in Amelia’s honour, less because she was the winner of a ghastly, low-rent, reality-TV show and more because she was their doted-on only daughter who’d soon be leaving London to return to Durham University for her final year where she might actually scrape through her degree in Art History with a 2.2.

An army of flunkies had spent most of the day transforming a restaurant in Chelsea into a distressed fairy grotto. There was ivy and other trailing green plants liberally strewn about, along with hundreds upon hundreds of tealights in glass holders. Adorning the rooftop bar was yet more artfully scattered foliage and paper lanterns, and it was there that George Wylie didn’t quite cut Amelia but made it clear that she could wait.

Amelia was very good at waiting for George. It was a running joke between their two families, that when Amelia Charlotte Louise Sedley was born, she’d marry George Wylie, eldest son of Sir John and Lavinia Wylie. Sir John’s great-great-great-great-great-grandfather had been a self-made man who made his money in the slave trade and bought his baronetcy, a fact which never failed to enrage his great-great-great-great-great grandson who longed to be aristocracy rather than merely landed gentry. The family fortune, built on the backs of men, women and children torn from their homes, had all but gone, most of it sunk into an ancestral pile that had almost killed Sir John’s father when a piece of decayed ornamental masonry had fallen inches away from him.

Sir John had had to do the unthinkable and restore the family’s failing fortunes by going into trade.

Trade had been very good to the Wylies, as had Mr Sedley, who’d initially provided capital and investment advice to young Sir John. Now, some thirty years later, George would never have to work a day in his life and could pootle about the estate killing any poor beast that flew across his land, scampered through his forests or swam in his streams.

However, George wasn’t content with a life of leisure. His years at Eton, then at Oxford (where he’d been a member of an infamous drinking club whose membership initiation involved setting a tramp on fire), were the perfect training for a bright young man from a good family who wanted to go into politics.

George currently worked at a right-wing think-tank while he and his backers waited for a safe Conservative seat to fall vacant. There was no rush. George wasn’t even thirty, though just as Amelia yearned for him, he yearned to make the Evening Standard ‘Thirty Power Players Under the Age of Thirty’ list.

In good time, Mr Sedley would make the perfect, political father-in-law, happy to bankroll his son-in-law’s campaigns with his many millions of pounds, but for now, Amelia held very little interest for him. George watched her visibly droop in the face of his casual indifference. She was easily one of the silliest girls he had ever met so he was quite happy to bide his time. He’d wait for Amelia to finish university and have her heart broken by someone who’d make George seem like quite the white knight when he finally made his move.

Her friend, on the other hand, wasn’t the sort of girl a man waited for. She was strictly right here, right now, don’t let the door catch you on your pretty little arse when you leave. George would swear on a thousand bibles that he didn’t watch reality TV but he’d somehow seen enough of Big Brother to get the measure of Amelia’s new friend.

The calculating glint in her downcast eyes. The steely determination behind that quivering bottom lip. Though she had a cracking pair of tits, he’d say that for her.

George smiled to himself, and, catching sight of his reflection in the mirrored wall behind the bar, couldn’t help but admire the jut of his own cheekbones. As he did, he caught the gaze of Amelia’s little friend, who had her eye fixed keenly on him. As if it were she who had his measure and not the other way round.

‘So what do you think of George?’ whispered Emmy, noticing Becky’s intent focus on her one true love.

‘You can do much better than him,’ Becky said to Amelia who immediately gasped in disbelief that anyone could find fault with George Wylie.

‘I couldn’t,’ Amelia declared. ‘He’s so handsome.’

Handsome was pushing it. George had a pale, interesting face, which reflected centuries of good breeding with the odd exotic import to keep the family line free of hereditary disease. His patrician features looked better in profile, though his body was sleek and supple, especially compared to Jos Sedley who had now lumbered over to George to reminisce about their time together at Eton.

‘Not that handsome,’ Becky said flatly, because she’d seen the dismissive way he looked at Amelia. It wasn’t with the tenderness of a man who’d treat her like the precious bauble that her family had raised her to be. There was no good reason for George to be so careless with Amelia’s affection when it was so unselfishly given. ‘Oh, don’t pout at me, Emmy! You should be pleased that the sight of Gorgeous George leaves me cold. You don’t have to worry that I’d steal him out from under your nose.’

‘I know that you would never do that!’ Amelia’s misguided belief in the goodness of Becky’s heart was interrupted by a Chelsea show pony who shouldered Becky out of the way so she could fall on Amelia.

‘Emmy! Oh my God! So glad you’re back from slumming it with the chavs!’ she cried and that was the cue for a whole pack of them – all with indentikit buttery, long limbs and sleek, shiny hair – to surround Amelia and squeal at a pitch that had every dog in the neighbourhood in a frenzy.

Becky had no choice but to step to the side or be mown down by a sharpened elbow or this season’s must-have heel.

‘How could you have kissed that awful Gav? He dropped his aitches more often than he dropped his trousers.’

‘You wouldn’t think they’d let people like that in the Marines.’

‘Was it very awful? The food looked terrible. And all that prosecco. Didn’t even give you decent bubbles.’

‘And as for that Becca girl. Common as the proverbial. What did she really say in that swimming pool? Go on! You can tell us.’

Amelia cast agonised glances between her Made in Chelsea crew and her new, common-as-the-proverbial BFF.

As it was a special occasion, Becky took pity on her. ‘It’s Becky, actually, and what I said in that swimming pool was, “If you chat shit about me again, I’ll wipe you off the face of the earth, bitch,”’ she recalled with the same menace that had made Leanne fall off the swan inflatable in fear.

The posh girls all took a synchronised step back, which was the first sensible thing they’d done.

‘Joke. That was a joke.’ Becky laughed lightly and stepped back into the circle so she could take a proprietorial hold of Emmy’s arm. ‘As if I would say something like that! And I wouldn’t say I was common. I mean, I don’t drop my aitches.’

‘You’re Bohemian,’ Amelia squeaked. ‘Becky’s parents were very artsy.’ The girls all sniffed: ‘Bohemian’ was secret code for ‘working class’. ‘Anyway, Becky, I want you to meet everyone. I know they’re going to love you as much as I do.’

It was doubtful that Minty, Muffin, Molly, Milly and Maddy would ever find it in their cold, solid-platinum hearts to love her. They each leaned in gingerly to kiss the air above Becky’s cheek as if she were covered in grime and smelt of body spray from Poundland, when actually she was freshly showered and doused in Mrs Sedley’s bottle of Coco by Chanel, which was far too young a scent for someone thundering through her fifties.

Becky might have been wearing another of Amelia’s old dresses and a pair of shoes with loo roll stuffed into the toes because they were a size too large, her pale skin unloved by the Mediterranean sun, but she refused to lower her eyes away from their collective, condemning gaze.

She was just as pretty as them, if not prettier. Besides, her beauty hadn’t been helped along by the attentions of a favoured plastic surgeon in Harley Street who’d given them all the same nose. Becky’s beauty had flourished in the harshest conditions, like a winter primrose fighting its way through frost to flower. Who knows what she might she have been with the advantages that these girls took for granted?

The Montessori nursery, the nannies, the private schools and personal tutors. The wholesome food, free of additives and E numbers, grown on the country estate or purchased by the housekeeper from London’s finest grocers. The tennis and ballet lessons. The holidays on exotic beaches and snowy ski slopes. The trips to art galleries and the theatre, Glyndebourne for the opera, Ascot for the racing.

If Becky had been born into that kind of privilege, there was no telling what she might have become.

‘You all look so glamorous,’ Becky said at last, so grateful to Jemima Pinkerton for ironing out her vowels so they were a lot less cockney and a bit more cut-glass. ‘I bet you’ve all been lounging somewhere lovely while poor Emmy and I were holed up in Elstree.’

‘Saint Tropez,’ Miffy admitted and Becky widened her eyes.

‘When my mother was alive, we used to summer in Cap d’Antibes. She was French, one of the Mortmerency family,’ she said a little wistfully. ‘We’d stay at La Belle Plage.’

It was the truth. Kind of. If you squinted at it and were already severely short-sighted. Her parents had met in Cap d’Antibes. Her mother and her mother’s mother had been chambermaids at La Belle Plage while her grandfather, pushing sixty, had never been promoted past busboy.

Her father had rolled into town one summer with a card-counting scam that had him thrown out of every casino within a fifty-mile radius. He also had three of his ribs broken and a mild concussion when he was roughed up by some casino heavies in the alleyway at the back of La Belle Plage, which was where Becky’s mother first laid eyes on him when she was rifling through one of the bins to find a pair of diamond earrings that she’d earlier thrown from a fifth-floor window.

It wasn’t so much love at first sight as like recognising like. ‘A girl after my own heart,’ her father would say when he was the good kind of drunk, pulling Sidonie on to his lap so he could kiss the top of her head.

When he was the bad kind of drunk, Sidonie was the one most likely to end up with broken bones and a mild concussion but still, it hadn’t all been bad.

There had been that one summer when the Sharps had slummed it on the Cap d’Antibes, staying on a nearby campsite and getting all gussied up to visit the family elders at La Belle Plage. Becky could remember being taken to the kitchens and treated like a visiting royal dignitary. There’d been a concoction of ice cream as big as she was and she’d sung an absolutely filthy song in French that her mother had taught her, much to the delight of the kitchen staff.

‘Good times,’ Becky sighed and now the show-ponies were looking at her as if maybe, just maybe, she wasn’t an irredeemable little chav.

‘Now you really must meet George,’ Amelia said urgently as if engineering an introduction between Becky and George was the only excuse she had for going to talk to him.

It was hot in the bar. The tealights had all but melted, the foliage had wilted and Amelia was ruddy-faced as she edged herself and Becky through the open doors that led out on to the roof terrace.

‘I’m pretty sure that I saw him slip out here when we were talking to the girls,’ she murmured as her eyes darted around the terrace, lit by paper lanterns and yet hundreds more tealights. Mrs Sedley had obviously sent a lackey to the nearest IKEA to buy out their entire stock. ‘Maybe he’s gone downstairs.’

‘Maybe George should chase you and not the other way round,’ Becky suggested because desperation was never a good look, but Amelia had her wrist in a surprisingly firm grip as she pulled Becky along.

There was a champagne bar in one corner and an oyster station in the other though Becky couldn’t think of anything more vile than sliding slimy, snotty oyster guts down her throat. Waiters circulated with canapés – an amusing affectation of tiny hamburgers, miniature newspaper cones of fish and chips, and hot dogs that could be eaten in one bite.