Полная версия

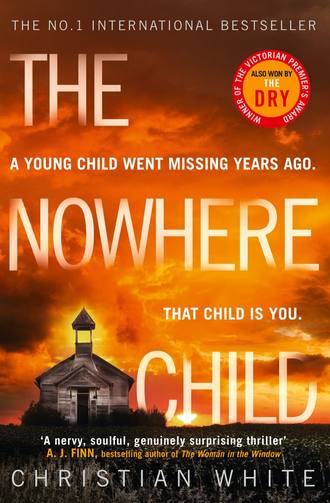

The Nowhere Child: The bestselling debut psychological thriller you need to read in 2019

‘Not by yourself, you won’t,’ Herm said.

‘I’ll be fine. Go on, now.’

The deputies left with purpose, and Ellis returned his attention to Molly and Jack. ‘What makes you think she was taken, Molly?’

‘Her window was open. Wide open.’

‘That doesn’t mean anything,’ Jack said. ‘You leave the window open all the time.’

‘I didn’t leave it open this time, Jack. I know it.’

‘You’re talking about her bedroom window?’ Ellis asked.

‘Sometimes I leave it open to let the breeze in. There’s no screen on it or anything, but it’s too high for Sammy to reach. Otherwise I’d never … Anyway this time I closed it. I specifically remember closing it.’

‘When was the last time you saw her?’

‘Around one,’ Molly said. ‘I don’t usually let her nap so late in the day because she ends up staying awake all night, but she was fussy and cranky and I just thought … I closed the window. I remember closing the window.’

‘Does the window have a lock on it?’ Ellis asked.

She shook her head.

‘The latch is broken,’ Jack added. ‘It’s been broken a while, but I wasn’t in a hurry to fix it because it’s on the second floor and, well, you know. It’s Manson. Not exactly the burglary capital of America.’

Ellis nodded. ‘And when you came back to check on her she was gone. Is that it, Mrs Went?’

‘I came in around two-thirty. Her bed was empty, and the window was wide open.’

Jack paced. ‘Look, Sheriff, I don’t want to act like an ass here, but she leaves that window open all the time.’

‘For Pete’s sake, Jack.’

‘I’m sorry, Molly, but you do. I don’t want to give the impression that the open goddamn window is some integral clue when there’s every chance you left it open yourself. The window is on the second floor, remember, so if she was taken, then it was by the world’s tallest man.’

‘Ever hear of a ladder, Jack?’

Jack threw up his hands. ‘Look, she probably just wandered downstairs and went outside. Maybe she, I don’t know, saw a bird or Grace King’s cat, and she followed it, got turned around …’

Molly rolled her eyes. The little boy in her arms dug in closer to his mother.

Ellis smiled at the boy. ‘And what’s your name, son?’

‘Stuart Alexander Went, sir,’ he said.

‘We call him Stu,’ Molly said.

‘Well, Stu, do you have any idea where your little sister might be hiding? Is there someplace she likes to play in the neighbourhood?’

Stu shook his head. ‘I dunno. Sorry.’

‘She’s not out there playing,’ Molly said coldly. ‘She didn’t see a bird or Grace King’s cat and she didn’t wander off on her own. Someone came in her window and took her.’

‘What time did you get home from school, Stu?’ Ellis asked.

‘He didn’t go,’ Molly said. ‘He’s getting over a cold. I thought one more day at home might help.’

‘Did you see anything strange today, Stu?’ Ellis asked. ‘Or maybe you heard something? A noise? Anything?’

The boy glanced at his mother, then shook his head. ‘I was playing Zelda most of the day.’

‘What’s Zelda?’

‘One of his Nintendo games,’ Jack said.

Ellis felt Emma’s eyes on his back, but as he turned to face her she looked at her feet.

‘How about you, Emma? Do you have any idea where your sister might be?’

She shook her head.

‘Did you notice anything unusual on your way home from school today? Anything at all?’

‘No. I-I don’t think so.’

It looked like she had something to say.

‘You sure? The smallest detail might end up being helpful.’

‘I told you; I didn’t see anything.’

Nodding, Ellis stood and turned back to Sammy’s parents. ‘Can I see her room, please?’

Sammy’s bedroom was a magical mess of pastel pinks and deep purples. A big toy chest in one corner was bulging with stuffed animals. On the walls hung framed pictures of Sammy’s family, some childish drawings, a giant pink ‘S’ covered with silver glitter, and two movie posters: Honey, I Shrunk the Kids and The Little Mermaid.

There were more toys on the bed – a couple of dolls and more stuffed animals. Marked against the tangled, unmade bed covers was the vague outline of a small body. Ellis’s stomach churned.

He went to the window. It was large enough for a child to crawl through, but far too high for a two-year-old to reach. Even if Sammy had managed to grab hold of the ledge, she’d never be able to hoist herself up. Also, the drop on the other side was close to twelve feet. Considering there wasn’t the limp body of a little girl in the garden bed below, it was a pretty safe bet Sammy didn’t go out the window – at least not on her own. ‘So this was open when you came in?’

‘Wide open,’ Molly said. ‘I checked outside for boot prints below the window or marks from a ladder, but I couldn’t find anything.’

Jack shot a glance at Molly.

Ellis put his back to the window and looked across the room, through the bedroom door and into the hallway beyond. ‘And this door was closed when you put Sammy down for her nap?’

‘No,’ Jack said. ‘We never close the door. Sammy can’t reach the handle and she doesn’t like being locked in. Right, Molly?’

Molly kept her gaze on Ellis. ‘She was being especially cranky, so I …’

‘You shut the door?’ Jack said. ‘She hates it when you do that.’

‘You weren’t here and you never are.’

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Where were you when I called the drugstore?’

‘Can we please do this later?’

Ellis turned back to the window and looked out. From this vantage point he had a clear line of sight over to the Eckles’ house. Afternoon was slowly shifting into evening, and the darkness creeping in over Manson felt heavy.

A weathered length of cord had been used in place of a latch. Ellis untied it and swung the gate open with an eerie, horror-movie creak. The NO TRESPASSING sign rattled in place. He looked up at the Eckles’ house, set deep in the yard, and started to walk.

Ellis had crossed this yard some years earlier, flanked by seven armed deputies. They were there to arrest Patrick Eckles for aggravated assault. Patrick had beaten Roger Albom’s head in with a pool cue over at Cubby’s Bar, and nobody had been exactly sure why.

The porch light buzzed on, exposing a broken screen door and a dusty old sofa. As the front door opened, some base, primal instinct sent Ellis’s hand to his holstered .45. He didn’t need to produce the pistol; he just needed to remind himself it was there. And it wouldn’t hurt to remind whoever answered the door too.

Ellis squinted into the dark of the house. A small woman stepped outside and into the light, can of beer in one hand, cigarette in the other.

‘Evening, Mrs Eckles. Mind if I have a quick word?’

Ava Eckles was an unremarkable-looking woman with tangled blonde hair, wiry arms and a fat, protruding belly. She wore black leggings and an old, loose-fitting, pink T-shirt on which Ellis could just make out the words 2% Angel, 98% Naughty.

‘I figured someone would be stopping by eventually,’ Ava said, dragging on her cigarette. ‘I’ve been watching your men all going door-to-door. Ours was the only place they didn’t visit.’

‘I need to ask you about Sammy Went. Jack and Molly Went’s daughter from down the street – you know ’em?’

By way of an answer she tossed her cigarette into the yard and lit another one.

‘Sammy is missing, Mrs Eckles. Did you see or hear anything unusual this afternoon?’

She folded her arms across her chest. ‘Only interesting thing I ever see ’round here is on the TV, Sheriff.’

‘Did you notice any unusual cars or people you didn’t recognise?’

She sucked on her cigarette and shook her head.

‘And you were home all day?’

‘Do I look like the sort of woman who has any place to be?’

‘What about your boy, Travis?’

‘What about Travis?’

‘Did he see or hear anything strange this afternoon?’

‘You’d have to ask him.’

‘I’d like to,’ Ellis said. ‘Is he home?’

‘He’s working.’

‘Is he still at Clinical Cleaning?’

‘It’s honest work.’

‘Won’t get no argument from me.’

Ava took a step toward him. She was a foot shorter than Ellis but possessed an unpredictable wildness that put him on edge. ‘You sure have a hard-on for this family, don’t you, Sheriff?’

‘I—’

‘Little girl goes missing and you assume an Eckles has something to do with it. It’s not enough you locked up one of my sons, now you’re looking to lock up the other.’

‘We’re asking everyone in the street if they’ve—’

‘I think it’s time you called it a night, Sheriff. If you stick ’round I’m likely to say something better left unsaid in polite society.’

‘What might that be, Mrs Eckles?’

She smiled then. Her teeth were small and yellow. ‘Well, as a for instance, I might say I don’t know what disturbs me more: opening my door to find a cop on my front porch, or opening my door to find a nigger.’

Ellis exhaled sharply. He hadn’t been expecting that. Anger and shame rose within like a geyser, but he supressed it. ‘One more question, Mrs Eckles. That work van your son drives ’round in. Does he keep a ladder in there?’

MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA

Now

There was a space in Dean’s driveway behind his Jeep and Amy’s Jazz, but I parked in the street in case I’d need a speedy getaway. He still lived in the same roomy three-bedroom house he had shared with my mother. It was painted in heavy browns and reds, but today a misty rain shrouded everything in grey.

My plan for our regular Sunday-night dinner – and the only way I could see to move forward – was to get everything out on the table. Chances were Dean had no idea about Sammy Went, and the news might shatter the way he remembered my mother. But on the drive over I’d decided that wasn’t my problem; this was happening to me, not because of me.

Dean greeted me at the front door with a big hug. As usual, he held the hug for three seconds too long. ‘God, Kimmy. You’re so skinny. Are you eating enough? Come in out of the cold.’

He was tall and lean and dressed like a sitcom dad from the nineties: white short-sleeved shirt tucked into blue jeans, white sneakers and a brown blazer. The blazer even had patches on the elbows. He ushered me through the front door and into the house. Scout, Dean’s thirteen-year-old cat and closest companion, skulked out to greet me. Or to judge me; it was hard to tell.

Amy, her fiancé, Wayne, and my niece, Lisa, were lounging in the living room around a crackling fire. Amy nearly jumped off the sofa when she saw me. She came over with a sad smile and grabbed both my shoulders. ‘Everything okay?’

‘Everything’s fine,’ I said.

‘No news on the thing?’

I flinched. ‘No.’

‘What’s the thing?’ Dean asked, arriving with two glasses of red wine and handing one to me.

‘Nothing.’ I drank half the glass with one gulp. ‘Hi, Wayne.’

‘Hello, Kimberly.’ Amy’s fiancé was the only person in the world who called me by my full name. He wasn’t a bad-looking guy – he might even have been handsome if he had any sort of personality. But he talked so rarely and so softly that it was easy to think he was just part of the house, an ornament found at the Sunday market that Dean hadn’t yet found a place for.

Dean sat down on the sofa, sipped his wine, smoothed the legs of his jeans and stood up again to tend the fire. He never stayed in one place too long.

‘Do you eat walnuts, Kimmy?’ he asked. ‘They have molecules that block the growth of cancer cells. I want you eating a kilo of walnuts a day. I’m not even kidding.’

‘A kilo?’

He disappeared again, returning moments later with an enormous sack of walnuts. He handed them to me, winked and said, ‘Farmers’ market.’

Everyone is afraid of cancer, but Dean’s fear bordered on irrational. Ever since it took his wife he’d been convinced it was waiting to take us all. He wasn’t so scared of getting it himself – he drank a little too much, and while he’d never admit it, his clothes occasionally smelled of cigarettes – but he was terrified it might come back to take another of his girls.

He pulled the grate aside from the fireplace and jabbed a burning log with an iron poker. Half the log collapsed into glowing red ash. ‘Hey, Wayne, would you mind fetching another log for the fire? They’re in the little crate thing on the back deck.’

Wayne stood up, gave a formal nod and left the room.

‘So, Kimmy, how’s life?’ Dean asked.

‘Same old,’ I lied.

Amy threw me a glance bursting with worry. Luckily, Dean was too engrossed in the fire to notice. ‘You know, I was at the shopping centre yesterday and someone was doing pet portraits, and I thought of you. She was making a killing. I was going to bring Scout in until I saw her price list. Forty dollars for three prints, and they’re not even framed. Can you believe that?’

‘She’s not going to take photos of pets,’ Amy said. ‘She’s got way too much talent for that.’

‘I’m not saying she should just take photos of pets. It would be a good way to make some extra cash with her photography, that’s all. She’s got that five-thousand-dollar camera just sitting on a shelf gathering dust. You know, sweetheart, I really wish you wouldn’t let Lisa drink so much cola. Do you have any idea what aspartame does to a developing body?’

Lisa was standing by the coffee table dunking her hands into Wayne’s Diet Coke and licking her fingers. She looked over at the adults with wide eyes.

Wayne came back into the living room cradling a long chunk of wood in his arms. ‘Where do you want this, Dean?’

‘Take a wild guess, Wayne.’

Dean had prepared a tuna pasta bake that smelled and tasted of nostalgia. He poured more wine, and I had to resist the urge to guzzle it. Lisa sat in the living room watching TV because she refused to eat at the table with the grown-ups. Amy and Wayne sat across from me, the former mournfully staring at me while the latter checked cricket scores on his smartphone.

‘Would you rather be stuck on a deserted island alone, or with your worst enemy?’ Dean asked. That was his thing. He asked thought-provoking questions at mealtimes to ‘stimulate interesting conversation, bring philosophy to the dinner table and to rise above the mundane’.

‘If your life was a movie,’ he might ask, ‘what would the title be?’ ‘What law, if any, wouldn’t you break to save a loved one?’ ‘What are the three most interesting things about you and why?’

He rarely repeated a question, and always had his own well-thought-out answer prepared. I happened to like this particular quirk, but Amy, not so much. ‘Come on, Dad,’ she said now. ‘You know I can’t enjoy my food when I have to use my brain.’

A memory came to me: sitting in my mother’s hospice room, with its yellow wallpaper and the faint smell of shit that we all silently agreed to ignore. Amy had brought in sandwiches, and we were eating them around the bed. Dean brought in some instant coffee from the machine in the hall, turned off the TV – nobody was watching it anyway – and asked, ‘If you could send a message to every single person on the planet, what would it be?’

‘It’s every night with him,’ my mother had said. She was breaking her sandwich into pieces instead of eating it. ‘Last night we ordered in a large pepperoni and as he’s opening the box, he asks me, “What would you change about your life if you knew you would never die?” I mean, what am I supposed to do with that?’

Before she got sick, my mother was a strong, compact woman with piercing blue eyes. By that night in the hospice every part of her had shrunk and yellowed, except for her eyes. They were the same blue all the way to the end.

Had she wanted to tell me the truth? I wondered. Did that make her last few months even harder than they needed to be? Maybe holding on to that secret was what killed her. Maybe holding in something like that, a secret so big and bad, manifested into—

‘Well, I’d choose to be marooned with my worst enemy,’ Dean said as the memory swept away. ‘Because bad company is better than no company, and if things got too tense between us, at least I’d have someone to eat.’

Amy looked at me over the table. ‘Remember when we were kids and Dad was the strong silent type? I miss those times.’

‘Speaking of bad company, what’s wrong with you?’ said Dean.

Amy had been in a mood all night. She had hardly said a word, and when she did it was short and abrasive. If it had been me nobody would have noticed, but when Amy turned shy it was a big red flag.

‘Huh? Oh yeah, I’m fine,’ she said.

‘She’s been like this all week,’ Wayne grumbled, still staring at his phone.

Dean leaned forward onto his elbows and studied Amy. ‘What’s going on, sweetheart?’

Amy glanced at me with an expression that seemed to say both tell him and don’t say a thing.

‘Fine,’ Dean said. ‘Forget my wonderfully thought-provoking and intellectual topic of conversation. Let’s talk about the weather, shall we? Or petrol prices, or politics.’

‘Let’s talk about Esmé Durand,’ Amy said.

‘Who’s Esmé Durand?’ Dean asked.

‘Do you remember my high-school friend Fiona Durand?’

Dean took a second to think it over. ‘Was Fiona the one who wet the bed?’

‘That was Michelle. Fiona was the redhead: petite, super cute. She was at Mum’s funeral.’

‘Was she the one who came home late after your deb and ate the last of my Jarlsberg?’

‘That was Natalie. The point is, her mother, Esmé, is single now. Her husband ran off with a woman from his work – he’s in finance or something, and she was his boss and, like, ten years older.’

‘Quite the scandal,’ Dean said, topping up his wine.

‘Yeah, so anyway, she’s single now.’

‘And?’

‘And she’s single, and cute, and I really think you guys would get along.’

‘Oh, well, thanks for the offer, Amy, but I don’t need my daughter to find me dates.’

‘Well, someone has to.’

He quieted then. ‘I’m not really looking for that sort of thing just yet.’

‘It’s been four years, Dad. Do you want to be alone forever?’

Her tone had turned hot and serious. Dean looked like a frightened mouse trying to escape a trap. ‘I’m fine, really. I just need to … It’s not that easy just to …’

‘Mum would have wanted you to find someone.’

‘Take it easy, Amy,’ I said. ‘He said he’s not ready.’

Her eyes turned red and wet.

‘What’s got into you?’ Dean asked, his own tone more serious now – and, if I had to guess, laced with a little anger. ‘Why are you crying?’

‘Nothing’s got into me,’ she snapped back, dabbing her eyes with her napkin. ‘I just don’t want you to be lonely.’

‘I’m not lonely. I have you guys, and Lisa, and Scout.’

Amy cried harder. Wayne sat and watched her with a stunned, terrified look on his face.

‘Darling …’ Dean moved to rise out of his chair, but Amy waved him away.

‘I’m fine.’

‘You’re the opposite of fine. What is it? Have I done something? Talk to me.’

‘This isn’t about you.’

‘Then what’s it about?’

She took the napkin away from her eyes long enough to glance at me. Then scornfully, bitterly, desperately, she said, ‘It’s about Sammy fucking Went.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.