Полная версия

The Good Mothers: The True Story of the Women Who Took on The World's Most Powerful Mafia

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2018

Copyright © Alex-Perry.com Ltd 2018

Cover image © Alamy

Cover design by Leo Nickolls

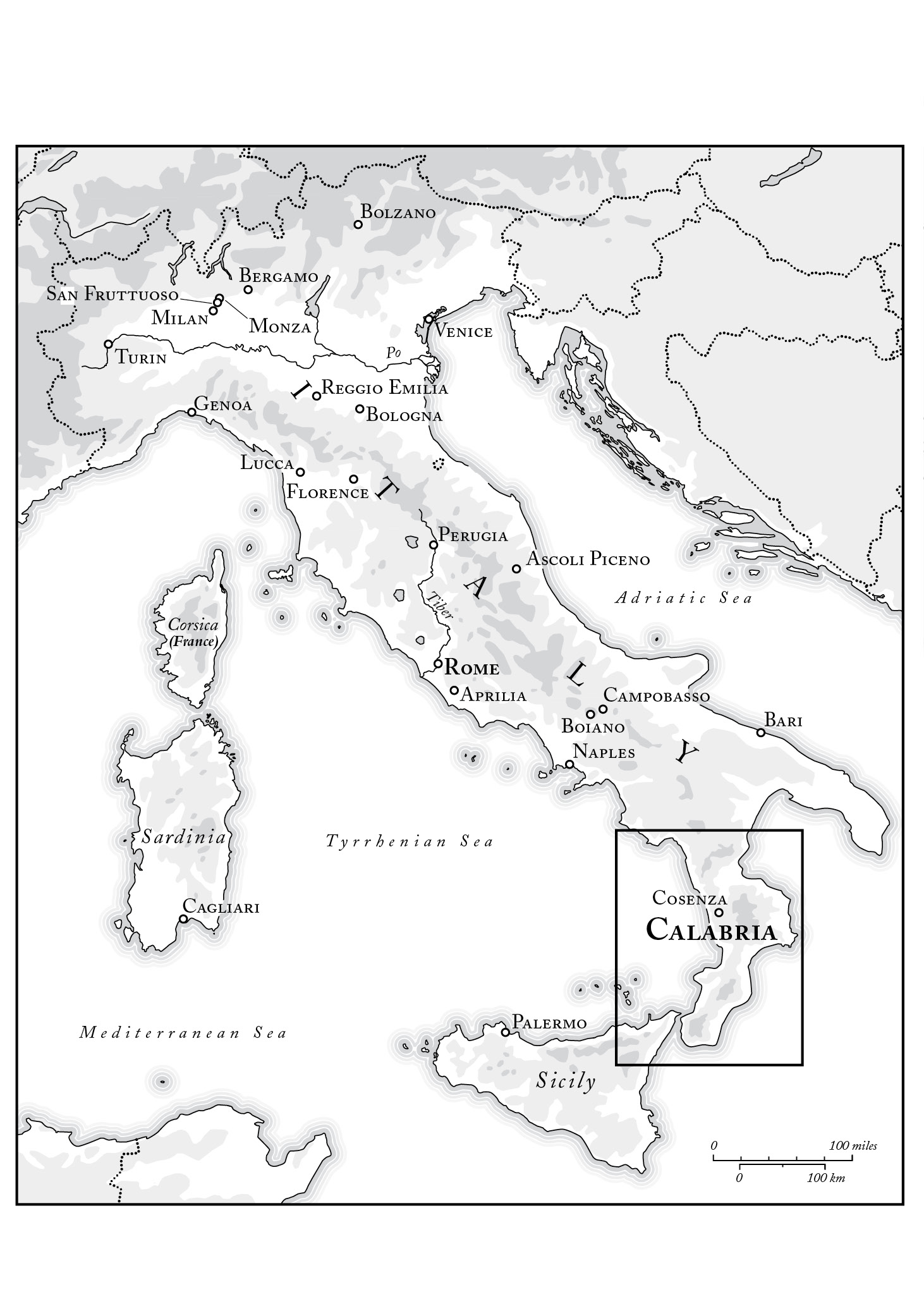

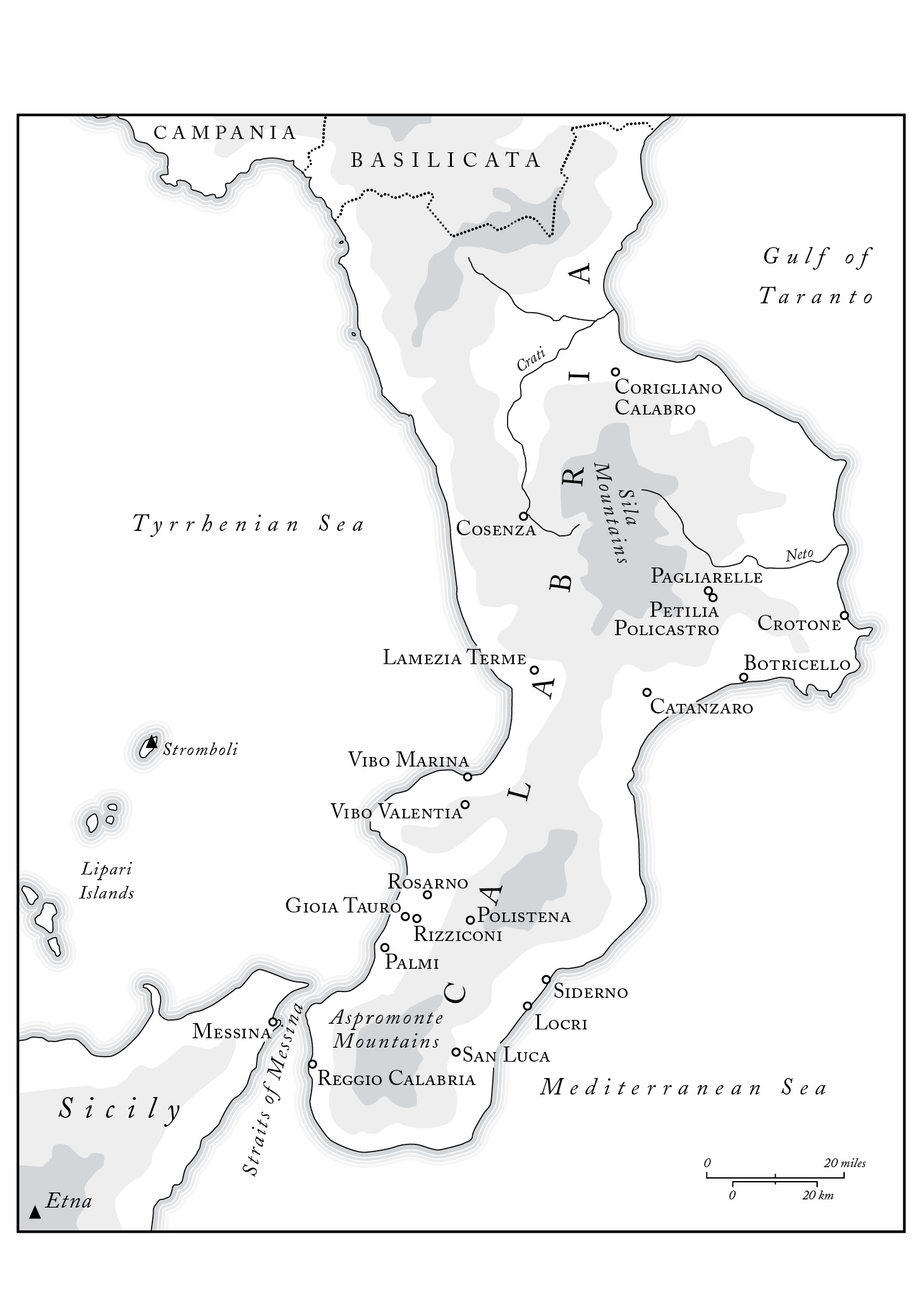

Maps by Martin Brown

Alex Perry asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008222109

Ebook Edition © February 2018 ISBN: 9780008222123

Version: 2018-02-01

Dedication

For the good daughters

and for Tess, always

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Maps

Author’s Note

ACT ONE: A VANISHING IN MILAN

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

ACT TWO: REBELLION IN ROSARNO

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

ACT THREE: ITALY AWAKES

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

XXV

XXVI

Acknowledgements

Notes

Picture Section

Index

Also by Alex Perry

About the Author

About the Publisher

Author’s Note

To assist the English reader, I have used anglicised place names: Florence not Firenze, for example. By contrast, I have observed Italian custom when it comes to individuals’ names. Maria Concetta Cacciola, for instance, becomes Concetta, or ’Cetta, at the second mention. In another difference from Anglo-Saxon custom, Italian women retain their father’s surname after marriage. Thus Lea Garofalo kept her name after she married Carlo Cosco but the couple’s daughter was called Denise Cosco.

I

The symbol of Milan is a giant serpent devouring a screaming child.1 The first city of northern Italy has had other totems: a woolly boar, a golden Madonna and, more recently, the designer labels that make Milan the fashion capital of the world. But the eight-hundred-year-old image of a curled snake sinking its fangs into the writhing, blood-soaked body of an infant has remained its most popular emblem, adorning flags and bas reliefs on the city walls, the Alfa Romeo badge and the Inter Milan jersey. It’s an oddly menacing standard for a people more normally associated with family and food, and a strangely crude one for a city whose artistry reaches the sublime heights of da Vinci’s The Last Supper – and most Milanese generally profess ignorance of its meaning. In more candid moments, however, some will confess they suspect that the image owes its endurance to the way it illuminates a dark truth at the heart of their city: that the dynamism and accomplishment for which Milan is famous depends, among other things, on who you are prepared to destroy.

In the four days they spent in Milan in late November 2009 before her father killed her mother, then erased any trace of her from the world, Denise Cosco could almost believe her family had transcended its own special darkness. Denise was seventeen. Her mother was Lea Garofalo, a thirty-five-year-old mafioso’s daughter, and her father was Carlo Cosco, a thirty-nine-year-old cocaine smuggler. Lea had married Carlo at sixteen, had Denise at seventeen, witnessed Carlo and his brother kill a man in Milan at twenty-one and helped send Carlo to the city’s San Vittore prison at twenty-two. Denise had grown up on the run. For six years, from 1996 to 2002, Lea had hidden herself and her daughter away in the narrow, winding alleys of the medieval town of Bergamo in the foothills of the Alps. Lea had made it a game – two southern girls hiding out in Italy’s grey north – and in time the two had become each other’s worlds. When they walked Bergamo’s cobbled streets, an elfin pair holding hands and curling their dark hair behind their ears, people took them for sisters.

One night in 2000, Lea glanced out of their apartment to see her old Fiat on fire. In 2002, after a scooter was stolen and their front door set alight, Lea told Denise she had a new game for them – and walked hand-in-hand with her ten-year-old daughter into a carabinieri station where she announced to the startled desk officer that she would testify against the mafia in return for witness protection. From 2002 to 2008, mother and daughter had lived in government safe houses. For the past eight months, for reasons Denise understood only in part, they’d been on their own once more. Three times Carlo’s men had caught up with them. Three times Lea and Denise had escaped. But by spring 2009, Lea was exhausted, out of money and telling Denise they were down to two last options. Either they somehow found the cash to flee to Australia, or Lea had to make peace with Carlo.

If neither was likely, reconciliation with Carlo at least seemed possible. The state had dropped its efforts to prosecute him using Lea’s evidence, and while that infuriated her, it also meant she was no longer a threat to him. In April 2009, she sent her husband a message saying they should forgive and forget, and Carlo appeared to agree. The threats stopped and there were no more burned-out cars. Carlo began taking Denise on trips around the old country in Calabria. One September night he even talked Lea into a date and they drove down to the coast, talking into the early hours about the summer they’d met, all those years before.

So when in November 2009 Carlo invited his wife and daughter to spend a few days with him in Milan, and Denise, her hand over the phone, looked expectantly at her mother, Lea shrugged and said OK, they’d make a short break of it. Lea’s memories of Milan in winter were of a cold, dismal city, the trees like black lightning against the sky, the winds tumbling like avalanches through the streets, driving small monsoons of icy rain before them. But Denise would love Milan’s shops, Lea and Carlo needed to talk about Denise’s future and ever since the summer Lea had found herself wondering about Carlo again. Twenty years earlier, he had held her face in his gorilla hands and promised to take her away from the mafia and all the killing – and Lea had believed him chiefly because he seemed to believe himself. Lea still wore a gold bracelet and necklace Carlo had given her back then. There was also no doubt that Carlo loved Denise. Maybe Denise was right, thought Lea. Perhaps the three of them could start over. The idea that Carlo’s new geniality was part of some elaborate plot to catch her off-guard was just too far-fetched. There were easier ways to kill someone.

Lea Garofalo had outclassed Carlo Cosco from the start. Carlo had earned his position with the clans but Lea was born a mafia princess, a Garofalo from Pagliarelle, daughter of east coast ’Ndrangheta aristocrats. Carlo was as broad and handsome as a bear but Lea was altogether finer, her natural elegance accentuated by high cheekbones, a slim frame and her long, thick curly dark hair. Carlo’s stuttering grasp of Italian and his sullen, taciturn manner was never more noticeable than when he was with Lea, who spoke with the sophistication of a northerner and the passion of a southerner, laughing, arguing and crying all in the same five minutes. In any other world, it would have been the natural order of things for Lea to have walked out on Carlo a few years into their marriage and never looked back.

At least Carlo was making an effort not to gloat, thought Lea. He had a friend drop round 100 euros for the train tickets to Milan. When Lea and Denise pulled into the city’s central station, Mussolini’s opulent glass-and-marble monument to northern order and power, Carlo himself picked them up in a black Audi and took them to the Hotel Losanna, a cosy backstreet place a block from the Corso Sempione, Milan’s Champs-Elysées, and a short walk from their old family apartment on Viale Montello. And for the next four days, Carlo refused even to discuss the past. He didn’t mention the ’Ndrangheta or how Lea had broken omertà or the way she almost destroyed everything for which he and his brothers had worked. Instead, Denise said the three of them enjoyed a ‘quiet and pleasant’ mini-vacation, the kind of family holiday they’d never had. Milan’s Ferrari showrooms and Armani stores were a million miles from the goat pastures of Calabria, and Carlo seemed happy for his wife and daughter to enjoy it. With his coat tugged around his shoulders in the Milanese style, and Lea and Denise in jeans and thick down jackets, the three of them wandered the canals and the polished stone piazzas, eating pizza and cannoli and window-shopping in the nineteenth-century galleria across from Milan’s flamboyant Gothic Duomo. Carlo paid for everything: clothes for Denise, dinners for the three of them, coffees and gelatos. Carlo even fixed it for the two women to get their eyebrows done at a beauty salon owned by his friend Massimo. Another time, when Lea was out of hash, Carlo summoned a cousin, Carmine Venturino, and made sure she didn’t pay.

It wasn’t perfect, of course. Denise was busy nurturing a teenage addiction to cigarettes and an aversion to heavy Italian food. Carlo, seeing his wife and daughter for only the second time in thirteen years and noticing how alike they were, couldn’t help be transported back to the day, nineteen years earlier, when sixteen-year-old Lea had eloped with him to Milan. Meanwhile Lea was struggling to hold her nerve. She’d asked Carlo not to tell anyone she was in Milan but already he’d gone ahead and introduced her to Massimo and Carmine, and Carmine, for one, seemed more than just a friend to Carlo. She also had the recurrent feeling that they were being followed.

Lea found herself turning to an old habit. Denise’s mother had long needed a joint or two just to get to sleep at night and, as the butts Denise found in their room attested, she was now also smoking steadily through the day. Sleep and peace were good, of course, and a real rarity for Lea. But you had to wonder at the wisdom of getting stoned around Carlo, a mafioso who had spent the last thirteen years chasing her across Italy trying to kill her.

Still, the trip went better than Lea might have feared. Initially, she had asked Denise to stay with her when Carlo was around because, said Denise, ‘if I was there, nothing was going to happen to her.’ Soon, however, Lea felt safe enough to be left alone with her husband. On the night of 23 November, Denise went to bed early and Lea and Carlo ate out alone. If the years had tightened Lea’s nerves, time seemed to have relaxed Carlo. He was now a barrel of a man, with thick ears, a close-shaven head and a boxer’s nose, but his manner was gentle and attentive. When Lea mentioned Denise’s plan to go to Milan University, Carlo offered to keep an eye on her. When Carlo volunteered that he’d set aside €200,000 for his daughter and Lea scolded him for the tens of thousands he’d spent trying to track them down – ‘and for no reason, because you always arrived too late!’ – Carlo, unusually, took the slight well. After he paid the bill, Carlo took Lea on a drive through the city, the pair of them gliding through the empty streets in silence, just taking in the sights and each other’s company. So distracted was Carlo that he ran a red light, delighting Lea, who was treated to the sight of the big mafioso trying to wriggle out of a ticket.

Watching them together in those days – Lea smoking and laughing, Carlo rubbing his bruiser’s neck and letting a smile soften his frown – Denise said you could see they had been in love once. You might even believe it would work out for the three of them. The three ‘ate together’ as a family, Denise said later. Carlo was showing them how ‘caring and kind’ he was. And there was no denying Lea still had it. Even without a cent in her pocket, and despite everything that had happened, her mother was still a rare and beautiful thing, a Calabrian forest sprite with the same pure spirit that had marked her out from every other girl in Pagliarelle all those years ago. Carlo, Denise felt sure, had to be falling for Lea again. ‘I had absolutely no bad thoughts about my father,’ she said.

Lea and Denise’s last day in Milan was 24 November 2009. The two women were planning to take the 11.30 p.m. sleeper back to Calabria. In their room at the Losanna, Lea and Denise packed. To help take the bags to the station, Carlo brought round a big grey Chrysler he had borrowed from a friend.

As he loaded their cases, Carlo asked Denise whether she’d like to eat that evening with her cousins: Uncle Giuseppe, Aunt Renata and their two boys, eighteen-year-old Domenico and Andrea, fifteen. Denise should grab the chance to spend time with her family, said Carlo. A night alone would also give her parents the chance to discuss a few last things.

Denise agreed. She and Lea then walked into town to do some final shopping. It was an overcast day, only just above freezing, and a dull chill echoed off the granite buildings. CCTV later showed Lea in a black jacket with its furry collar turned in and Denise in a thick white jacket with her hood up and a black backpack over the top. Mother and daughter wandered around the arcades, warming themselves in cafés and grabbing lunch at a McDonald’s, just happy to be out together in the city and, for once, not looking over their shoulders.

An hour after dark, just before 6 p.m., Denise called Carlo. She and Lea were near the Arch of Peace in Sempione Park, not far from the hotel, she said. A few minutes later, Carlo arrived in the Chrysler, flicked on his hazard lights and reminded Denise through the driver’s window that she was expected for dinner with her cousins. Lea, who had already got in the car, didn’t want to go: even if she was getting on better with Carlo, she wanted nothing to do with his family. Carlo suggested he drop off Denise, then return to take Lea out for a quiet dinner. After everyone had eaten, Carlo and Lea would pick Denise up again and all three of them would head over to the station. The women agreed. ‘See you at the station, mama,’ said Denise to Lea as she jumped into the car. ‘Later,’ replied Lea, getting out. ‘I’m going to have a drink.’

Carlo drove Denise to No. 6 Viale Montello on the edge of Milan’s Chinatown. A large, grubby six-storey walk-up of more than a hundred apartments arranged around a drab internal courtyard, No. 6 Viale Montello had once belonged to the Maggiore Ospedale, one of Europe’s first public hospitals when it opened in 1456. But the place had fallen into disrepair and was later abandoned, and in the 1980s the ’Ndrangheta from Pagliarelle had taken it over as a live-in hub for their heroin and cocaine business. The ground floor was now filled with half a dozen cheap Chinese stores – groceries, laundries, tabacs – whose metal shutters were decorated with extravagant graffiti. Most of the apartments were home to immigrants from China, Romania, Albania, Poland, Eritrea and Nigeria, tenants whose own uncertain legal status ensured they were no friends of the law. The rest was given over to around a dozen mafia families. Carlo, Lea and Denise had lived in one apartment in the early 1990s. Carlo’s elder brothers Vito and Giuseppe were still installed in others with their wives and children. It was to these rooms that tons of cocaine and heroin were transported every year before being repackaged and shipped north into Europe.

Carlo left Denise with her Aunt Renata at 6.30 p.m. at Bar Barbara, a Chinese-run café on Piazza Baiamonti at the end of Viale Montello, then drove off to fetch Lea. Denise ordered an espresso. Renata said dinner was minestrone and cold cuts. Denise told her aunt she wasn’t all that hungry, so she and Renata went to an Asian supermarket a few doors down to buy her a small tray of sushi. Denise tried to pay but Renata wouldn’t hear of it.

Looking back, Denise would say it was around then that the make-believe stopped. Back at her cousin’s second-floor apartment in Viale Montello, Denise ate her sushi alone. Then she sat with Renata, Domenico and Andrea as they had their soup and meat in front of the TV. Far from the family get-together Carlo had described, her cousins were in and out all evening. Her Uncle Giuseppe wasn’t even home, which was doubly strange as there was a big game that night, AC Milan away to Barcelona. There was something else, too. When Denise had spent time with Renata before, she remembered thinking that her aunt was a jealous wife, always calling Giuseppe to ask where he was, who he was with, what he was doing and when he was coming home. That night, Denise noticed, Renata didn’t call Giuseppe once.

Denise, who after years on the run had developed a sixth sense for these things, began to feel something was off. Around 8 p.m. she called her mother. Lea’s phone was unobtainable. That was odd too. Lea always made sure her phone was charged. Denise sent her mother a text. ‘Something like “Where the hell are you?”’ Denise said later in court.

The big game started at 8.40 p.m. Barcelona scored quickly. Denise texted Lea a couple more times. Still no answer. Renata told Denise not to worry about smoking in front of the family – no one would tell Carlo – and as the evening wore on, Denise found she was chain-smoking. Her cousins groaned as Barcelona scored a second goal just before half-time. Sometime after 9 p.m., just when Denise was beginning to feel truly unnerved, Giuseppe stuck his head around the door, registered the score and Denise’s presence, then left again. A few minutes after that, Denise’s phone rang. It was Carlo. He would be over in a few minutes to pick Denise up to take her to the station. She should wait for him downstairs at her Uncle Vito’s first-floor apartment.

Denise kissed her cousins and her aunt goodbye, then took the stairs to Vito’s. Carlo hadn’t arrived so Vito’s wife, Giuseppina, made coffee. It was after 9.30 p.m. now – more than three hours since Denise had last heard from her mother – and she was fighting a rising sense of panic. After a while, Vito appeared at the door. Behind him, down the corridor, Denise caught a glimpse of her father at the entrance to another apartment. She hadn’t even known Carlo was in the building. Instead of fetching her, he was talking to his brother Giuseppe and two other men. Carlo glanced at his daughter, and called over that she should wait for him in the car. Denise went down to the street and found the Chrysler. Lea wasn’t in it. By now, it was 10 p.m. When Carlo got in, Denise asked him immediately: ‘Where’s my mother?’

‘I left her around the corner,’ replied Carlo. ‘She didn’t want to come in and see everyone.’

Carlo drove in silence to a street behind Viale Montello. Denise regarded him. He looked upset, she thought. The way he was driving, barely focusing on the road. ‘Scossato,’ she said later. Shaken.

When they turned the corner, Lea wasn’t there. Denise was about to speak when Carlo cut her off. Lea wasn’t waiting for them, said Carlo, because what had happened was that Lea had asked him for money and he had given her 200 euros but she had screamed at him that it wasn’t enough, so he had given her another 200 but she’d stormed off anyway. They hadn’t eaten dinner. Actually, said Carlo, he hadn’t eaten at all.

Carlo fell silent. Denise said nothing.

You know what your mother’s like, said Carlo. There’s nothing anyone can do.

Carefully, Denise asked her father, ‘Where is my mother now?’

‘I’ve no idea,’ replied Carlo.

Denise thought her father was a terrible liar. ‘I didn’t believe him for a nanosecond,’ she said. ‘Not one word.’ All his kindness over the last few days, all the opening doors, fetching coats and driving them around – his whole Milanese bella figura act – all of it was gone. Carlo appeared to have regressed. He seemed raw, almost primal. He wouldn’t even look at her. And suddenly Denise understood. The dinner with her cousins. The calls to Lea that wouldn’t go through. The endless hanging around. The urgent discussion between the men in the apartment opposite. Lea had been right all along. Denise, who had begged her mother to let them go to Milan, had been catastrophically wrong. ‘I knew,’ said Denise. ‘I knew immediately.’

Denise understood two more things. First: it was already too late. Denise hadn’t spoken to her mother for three and a half hours. Lea never turned off her phone for that long and certainly not before telling Denise. It’s done, thought Denise. He’s already had time.

Second: confronting her father would be suicide. If she was to survive, in that moment she had to accept Lea’s fate and fix it in her mind not as possible or reversible but as certain and final. At the same time, she had to convince her father that she had no idea about what had happened, when in reality she had no doubt at all. ‘I understood there was very little I could do for my mother now,’ said Denise. ‘But I couldn’t let him understand me.’ Inwardly, Denise forced her mind into a tight, past-tense dead end. ‘They’ve done what they had to do,’ she told herself. ‘This was how it was always going to end. This was inevitable.’ Outwardly, she played herself as she might have been a few minutes earlier: a worried daughter looking for her missing mother. The speed of events helped. It was absurd, even unreal, how in a moment Denise had lost her mother, her best friend and the only person who had ever truly known her. She didn’t have to pretend to be struggling to catch up. She even had the feeling that if she willed it hard enough, she might bring Lea back to life.

It was in this state, with Carlo in a daze and Denise acting like there was still hope in the world, that father and daughter drove all over Milan. ‘We went to all the places we had been,’ said Denise. ‘Where we’d had a drink, where we’d eaten pizza, the hotel where we had stayed, over to Sempione Park. We went to a local café, a shopping centre, the McDonald’s where we had lunch and the train station, where my father bought two tickets for my mother and me. We went all over the city. I was phoning and texting my mother all the time. And of course, we found nothing and nobody.’