Полная версия

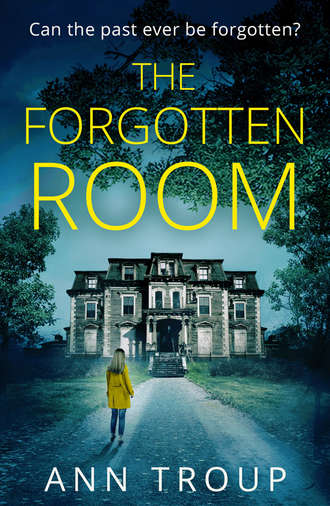

The Forgotten Room: a gripping, chilling thriller that will have you hooked

Cheryl didn’t catch the joke and frowned. ‘Might not be a bad idea. Anyway, I’ll show you around and then take you to meet him.’

Maura drained the last of her piss-weak tea and followed Cheryl out into the chill grasp of the house. She was about to ask where Dr Moss had gone, but realised this would reveal she’d been listening outside doors. Cheryl was abrasive enough, without Maura rubbing her any further up the wrong way. The woman’s hostility already came off her in sharp spikes, like static electricity that snapped and bit whenever anyone got too close. Cheryl’s welcome had been as bitter and cold as the house itself. For Maura, it didn’t bode well, but she had to admit she felt sorry for the woman.

Chapter Two

‘Got to watch yourself. It’s not such a big place, but there’s nooks and crannies and it’s not hard to lose your bearings. Sometimes I think they just tacked this place together without rhyme or reason. Just stick to where I show you, and don’t wander off. There’s nothing to see anywhere else anyway and some bits are dangerous so you’d be wise to not stray,’ Cheryl said as she led the way past an array of rooms, few of which seemed to be in regular use. They were too tidy, too quiet and seemed to be holding their breath as if waiting for someone else to breathe first. The creeping sensation of waiting for that breath to linger on the back of your neck was a haunting thought, forcing Maura to view the rest of the building with a fair degree of caution. She wasn’t easily spooked, but the atmosphere was solemn, giving the place a sepulchral feel that settled into her bones like a deep-seated and ice-cold itch that had burrowed into the marrow and would not be shifted. She was being dramatic and she knew it, but Cheryl had an air about her that was echoed in the feel of the house, as if they shared a twin, hollow soul.

Maura’s bedroom was a pink-chintz nightmare that looked as if it had last been decorated somewhere circa 1935. Faded, overblown roses scrambled across the wallpaper in a busy tangle, while the ditsy curtains looked as if they were succumbing to a slow death from the constant onslaught of sunlight and moth. She couldn’t anticipate trying to close them without the thought that they would disintegrate at her touch. The room might have been quaint and charming in any other house but here it made Maura long for her ten-tog duvet and central heating. As she looked around she felt a pang of homesickness and a hunger for the comfort of familiar things.

It seemed that Cheryl had read her thoughts. ‘Don’t mess with the curtains, will you? They’re a bit delicate, ever so old they are, but her ladyship calls them vintage. You can use the bed curtains if you want to shut out the light.’

Maura eyed the four-poster with its swags and tails and thought that the last thing she’d want to do in a house like this was shut out the light. ‘Do you have to address her as your ladyship?’

‘Good Lord, no, that’s what I call her behind her back. She’s got a few too many airs and graces for my liking. No, I call her Miss Hall. Her ladyship indeed…’ Cheryl scoffed, shaking her head.

‘Fair enough,’ Maura said, feeling slightly embarrassed at her assumption. Cheryl was a strange woman, prickly and intense one minute, warm and friendly the next. It was an intriguing yet repellent mix and reminded her of why she’d wanted to become a nurse. People were fascinating in all their shades of light and dark.

Back on the landing Cheryl pointed down the hall. ‘They don’t use that part of the house, it’s not safe, so don’t be going wandering. There’s nothing for you down there. His room is there, opposite yours, but he sleeps downstairs most of the time. We just use it to store his clothes – he can’t be trusted with them downstairs. Hers is two doors down from you.’ She led the way, their footsteps inducing creaks of protest from the old stair treads as they descended. Cheryl pointed to the one room she hadn’t already shown to Maura. To her dismay the door had a security chain attached to the outside. ‘Make sure to put that on at night – he likes to wander,’ Cheryl said.

Maura couldn’t help herself. ‘I’m not sure I’m keen on the idea of locking him in his room!’ The idea was abhorrent to her. She hadn’t come to the Grange to look after the man by shutting him away and denying him his freedom. She’d hoped to bring him care and comfort. She wanted to give the best of herself, not be a jailer.

Cheryl’s eyes widened, as if she was surprised to be dealing with someone who could be so naïve. ‘It’s either that or chase him around the bloody estate in the dead of night. If you know what’s good for you and him, you’ll put the chain on. Besides, we don’t want him taking a tumble too, do we? You mustn’t let him near the stairs. Like I said, the old part of the house is dangerous.’ She said this as if Maura might not have heard her the first time.

Maura saw the wisdom in keeping her mouth shut at this, but she remained unhappy about the use of the chain. She forced a smile. ‘I suppose I’d better meet him, hadn’t I?’

Cheryl chuckled. There was no warmth to her laugh and it sounded as mean and thin as her tea. ‘Suppose you better had. Brace yourself.’

Gordon Henderson was on the floor, sitting in a puddle of his own urine and looking up at the two women with the innocence of an untrained puppy when they entered the room. ‘Don’t be fooled, this is all for your benefit,’ Cheryl whispered.

Maura was too busy trying not to gag on the stench of ammonia that stung her eyes and burned her nose to pay much attention to Cheryl. This wasn’t the first time the old man had peed himself by the smell of it. She glanced at Cheryl, who seemed to be immune to the fumes.

‘Best get you up, Mr Henderson, eh?’ Cheryl said, speaking to the man as if he was a deaf five-year-old.

He raised a thin hand and pointed a wavering skinny finger at Maura. ‘She can do it, not you.’

Cheryl sighed. ‘Whatever. I’ll get you some clean clothes.’

Maura knew instinctively that she was being tested, perhaps by both of them. ‘OK, but introductions first. I’m Maura. I’m going to be staying with you until Miss Hall is recovered. I’m a nurse, I’ve come to take care of you, and Miss Hall when she comes home. I’ll be here until she gets better.’ She added what she hoped was a reassuring and confident smile. ‘Right, I’m going to crouch in front of you and I want you to put your arms around my neck. Then I’m going to lift you into a standing position. Do you think we can do that?’

The old man nodded, but there was a cold sparkle in his eye that invited caution. Maura was not unfamiliar with the wiles of awkward patients, and the likes of Gordon Henderson were ten a penny, nasty old men with a touch of the vicious. Not all of them could be changed by good nursing and a dose of compassion but she was prepared to give it her best shot. She crouched down in front of him and placed her arms around his back under his arms – he had the thin frame of a waif, but looked tall. She hunkered in, ready to lift from her knees to save her back. It wasn’t ideal, but he couldn’t stay on the floor, so she had no choice but to lift him badly. He slipped his arms around her neck and leaned in. His breath was sour and smelled of pear drops – ketones, which told Maura he wasn’t eating well, so no wonder he was so thin. She tightened her hold and began to lift, hauling him to his feet in one deft move. Once upright, he turned his lips to her cheek and, for a fraction of a second, she thought he was going to kiss her. Then he opened his mouth and took the flesh of her cheek between his teeth and bit down, holding her skin at a point where damage might be done if he felt the urge for it.

She didn’t flinch. It was an old trick. ‘Mr Henderson, if you continue, and you bite me, I will drop you straight back on your backside, call the police, tell them I’ve been assaulted, and they will come here and take one look at you, and you’ll be in a psychiatric unit quicker than either of us can reconsider our decisions. Do you understand me?’ They were harsh words, but she needed to set some boundaries if they were to come to terms with each other. She’d never be able to nurse him if he thought she was afraid. She was, but he didn’t need to know that.

He didn’t move. His teeth remained on her skin and she could feel his thin body quivering with malice. ‘I’m here to care for you, not to put up with abuse. I don’t care how ill you are, I will not put up with abuse – do we understand each other?’ She had come full of good intentions, hung on to them despite her instincts, but they were waning fast. Maybe she wasn’t ready for this after all. The sight of the little girl and all the reminders of why Maura had become a nurse had fuelled her enthusiasm and conviction and made her remember her compassion. She’d wanted to be kind, to show she was still a decent person and could still care, but this man was sucking it all away by the second.

It took a moment, but eventually he relaxed both his grip around her shoulders and his hold on her cheek, but it bothered her that he’d had to think about it for so long. There seemed to be a streak of cruelty in Gordon Henderson that had the potential to send shivers crawling down the spine. He stank, not only of piss, but of evil, and the combination made Maura’s gut churn again. The feeling did not abate when he whispered in her ear, ‘There’s bad in this house, mind you be careful of it. It gets us all eventually. Ask the nurse, she’ll tell you.’

‘I am the nurse, Mr Henderson,’ she said. Her instinct was to shove him away from her, but she couldn’t. He was old, frail and demented if the agency was to be believed. No wonder they were paying so well; no one in their right mind would have taken this job on. But Maura wasn’t in her right mind – the pack of Prozac that lay in her bag unopened was proof of her own GP’s belief in that. Maura was desperate and lonely and full of self-pity. The depression was telling her she wanted to foist that pity onto someone else so she didn’t have to feel it herself any more. Coming to the Grange hadn’t been an act of altruism, it had been an escape route. She had hoped this elderly man would an eager recipient of her willingness to care, no matter how poor the reason, but it seemed she had made a mistake there too. She wasn’t ready, and no matter how mean and vile Gordon Henderson appeared to be, he deserved better. Everyone deserved better.

Instead of pushing Gordon away she held firm, resolving to call the agency the next day and ask to be replaced by someone who was up to the job. They could have the money; she didn’t want it. She just wanted to feel useful again and keep hold of a good mood when it came along.

Cheryl came back into the room carrying clean underwear, trousers and a pack of baby wipes.

‘Soap and water would be better,’ Maura said, which got her an impatient scowl from Cheryl and a smug smile from Gordon Henderson.

‘You can always go and fetch some if you’re so keen,’ Cheryl said impatiently. ‘I’ll hold him, you clean him up.’

For the sake of cordiality, Maura caved in and took the baby wipes. No wonder the salary for this job had been so generous. She assumed it was Dr Moss who had wanted private nursing care; he must have known that whoever he hired would have their work cut out. If the bastard had asked for her by name, she would make him pay. They had never seen eye to eye and his presence in the house earlier had felt like much more than a coincidence. She didn’t know who she was most angry with, herself or Dr Moss.

Gordon stood patiently and compliantly while Maura stripped him of his trousers and underpants, a smile of victory playing around his mouth. She asked him to step out of his wet clothes and he did so without complaint, holding on to Cheryl’s shoulders while she looked away in disgust. The only frisson of trouble occurred when Maura pulled a few baby wipes from the packet and asked him to clean himself up. He hesitated, looked confused, then angry. ‘I do not do these things for myself,’ he said with more coherence and pomposity than she’d expected from a man who was supposedly terminally demented.

‘And I don’t get paid to do things for people who are perfectly capable of doing them for themselves, Mr Henderson.’ She held the wipes out. He stared at them for a moment, glowered at her, then took them and did as he was asked.

It was a dance, a setting out of the rules of engagement, and it happened with everyone. Maura was used to it, wise to it, and, nine times out of ten, could outstep the opposition in three moves flat. With Gordon Henderson it just took the two, but there was a good chance he would muster and try it on again. She wasn’t being cruel, far from it. Despite her feelings about the Grange and its owner, she’d be a poor carer if she did too much for him. The goal was independence and her job was to help him maintain it.

She helped him into his clothes while Cheryl fetched tea and he was as docile as a lamb the whole time. Once she’d got him settled in his chair she sat down opposite him. ‘So, Mr Henderson, is there any particular reason you couldn’t make it to the toilet?’

He looked away from her and mumbled something she couldn’t quite make out. ‘I didn’t quite hear you.’

‘I said I find you very rude.’

‘And I find you very difficult, Mr Henderson, so we can either battle it out while we both have a really horrible time or we can call a truce and try and work with each other – what’s it to be?’

‘If either of us lasts that long,’ he said, avoiding her gaze. She was in no mood for amateur dramatics and chose to ignore him, busying herself tidying the dirty clothes. Feeding into it would do neither of them any good.

By the time Cheryl had come back with his tea – weak, splash of milk and precisely a quarter level teaspoon of sugar – he seemed to have got the measure of Maura and decided to play ball. For now.

According to Cheryl’s crib sheet, Gordon normally took a nap after his afternoon cuppa, so they left him to doze in his armchair.

As they walked back to the kitchen, Maura asked Cheryl what had happened to Miss Hall. ‘Daft old bat took a tumble down the stairs, broke her hip, bashed her face into the newel post and bust her jaw, according to Dr Moss,’ Cheryl said, painting the picture for Maura. ‘Nasty do, I reckon. Mind you, it isn’t half quiet round here without her – quite demanding is our Miss Hall.’

Maura seized her chance. ‘I don’t know of any local GPs of that name. The only Dr Moss I know is a consultant in psychiatry.’

‘Yes, that’s him. He’s their doctor, has been for years. They go private, see?’

It seemed an odd set-up to Maura. OK, all psychiatrists had to have basic medical training before they specialised, but it was the first time she’d heard of one dealing with general medicine privately. ‘They don’t have contact with a local GP?’

Cheryl paused by the door and turned to Maura, a puzzled look on her face. ‘Why would they? There’s no need. Dr Moss takes care of everything for them.’

Maura could bet he did, and no doubt he billed them handsomely for it. He was notoriously flash, which was why she’d been surprised not to see his sleek Lexus parked outside.

They made for the kitchen via the bloody baize door and all it represented. Maura knew she was about to be abandoned and the thought filled her with the kind of anxiety she hadn’t felt since she was a child.

‘Right, that’s me done for the day. I’ll be back in the morning at nine so all you have to do is make his porridge like I told you, and don’t forget he likes his toast with the crusts cut off. Don’t forget his cocoa at nine-thirty, and his hot water bottle, and I need to give you the key for the medicine cupboard,’ she said, slipping her arms into a faded blue mac. ‘His pills come in one of those reminder thingies, so all you have to do is dole them out in the right colour order – don’t get them mixed up or he’ll refuse to take them. And make sure the old sod doesn’t palm them or hide them under his tongue – he’s a bugger for that and a nightmare if he doesn’t take them.’

Maura nodded and held her hand out for the small key that Cheryl had taken from the bunch in her pocket. Abrasive though the woman had been at times, Maura felt a ripple of trepidation at the thought of her departure and the prospect of being left alone in the house. None of it had turned out as she had expected: the house was a maze, the patient was a nightmare and, despite the new housing estate being less than a quarter of a mile away in any direction, she felt as though she might as well have been abandoned in some remote castle in the middle of nowhere. ‘Who do I contact if anything goes wrong or there’s a problem?’

Cheryl looked heavenwards in a gesture that smacked of sheer despair and judgement. ‘There’s a list of phone numbers stuck on the side of the fridge. Don’t call me because I won’t come out at night. If anything goes wrong with him just call the doctor. If it’s anything else you can call Bob, the gardener and odd-job man – lives in a bungalow at the bottom of the orchard. He’ll come out if you need him. Just stick to what you’ve been told, don’t go poking around, and nothing will go wrong.’

Maura glanced at the list and wondered whose name had been scribbled out and why they were no longer a contact. The paper itself was old, yellowed and curling at the edges, yet the name and number had been obliterated recently judging by the bright colour of the pen marks. It seemed someone had fallen out of favour. She contemplated ringing Bob to see if he wanted to come and keep her company, which was an utterly ridiculous idea and more pathetic than she wanted to admit. The sound of his name, its ordinariness, had implied something comforting, something normal, something she instinctively felt was rare in the Grange. ‘Thanks, Cheryl, I appreciate your help.’

Cheryl gave her a brief nod and a “huh” then left unceremoniously. Leaving Maura standing in the brightly lit kitchen, hugging herself and wondering what on earth she was going to do until Gordon needed something and she had a purpose again.

Without Cheryl’s shrill voice to dominate her attention, the house was far from silent. In fact, now she was listening, it seemed to be cracking its knuckles and flexing its muscles through a series of creaks and groans, as if it was getting ready to tussle with her. The Grange struck her as a place where it would be easy to lose your sense of self and your grip on real time. It was old and grudging, full of dogged antiquity in the form of ancient furniture, faded formality and pointless knick-knacks. Maura hadn’t paid detailed attention to them but she knew they were there, oozing claustrophobia and gloom. The place felt as though it was stuffed to the gills with the collected kitsch of generations and all those long-dead Hendersons still making their presence felt, lurking in the shadows and breathing down her neck.

Maura took a breath – she had lived with worse shadows than the phantoms of dead gentry. It was going to take more than an ugly house and an overwrought imagination to faze her. Her logic agreed, her instinct did not – it was still grumbling away and sulking in her gut.

Though Cheryl had shown her around, it had hardly been a detailed tour, just a quick glimpse into too many rooms, most of which had seemed to be swathed in dustsheets. It seemed sensible to make a more exacting trip around the place, familiarising herself with the layout and the lifestyle. If she was going to look after Gordon in any meaningful way, it might help to get to know how they’d lived before he’d been confined to a single, stinking room and old age had got the better of him. Even if she was going to abandon ship, she would have to do something about that room, and not just the smell. It hadn’t escaped her notice that Gordon was a hoarder and had crammed his room with all manner of detritus. Given the ordered clutter of the rest of the house, it was clear to Maura that interfering with his living space was likely to upset him. As abrasive as Cheryl had been, she didn’t seem the type to leave a room unclean if she could help it, and from the little Maura knew of Estelle Hall, she didn’t come across as the type of woman who would tolerate disorder unless it had been foisted upon her. Gordon seemed to have entrenched himself in his pit and surrounded himself with things that brought him security, things that would distress him if they were interfered with, just as altering his routine, his food and his medication were likely to disturb him. Though it wasn’t Maura’s role to diagnose, it was certainly her job to assess, and in her opinion Gordon was suffering from obsessions and compulsions just as much as he might be from dementia. He also seemed to suffer from terminal unpleasantness, something that wasn’t entirely unexpected but that might prove to be a stumbling block to even the shortest therapeutic relationship.

She pondered this a while as she re-explored the house, taking her time on this occasion, not prying where she’d been told not to but soaking the whole place up and making peace with it in her mind. Weeks of being afraid of a building were not an item on her agenda and she refused to allow the atmosphere of the place to get any further under her skin. She had suffered enough cowed defeat lately; there was no way she was going to let a pile of bricks and mortar rattle her, no way on earth. If she and the house were going to engage in a battle of wills over whose personality was going to win, Maura was going in all guns blazing. Its shadows were just shadows, its creaks and moans just its twisted old bones settling, its air of impending menace just her imagination running away with her. Its residents? Just an elderly, frail man in need of her help and a slightly bonkers housekeeper who seemed to have learned her people skills from the Mrs Danvers school of charm. Despite that, Maura had quite taken to Cheryl, even if it was with the utmost caution.

‘Get a grip, Maura,’ she said to the empty kitchen. ‘You’re getting far too cynical and curmudgeonly. Make yourself a cup of decent tea and crack on with it, kid. You’re moving on, remember?’

The statement was as hollow as the echo in the empty room and, despite her bravado, Maura couldn’t stand it. There was a radio standing on the kitchen counter – old and grubby, but functional. She switched it on and cranked up the volume a couple of notches, smiling at the irony of the song that was playing. “I Put a Spell on You…”

And now you’re mine…

Chapter Three

Maura lay in her bed clutching the camphor- and lavender-scented sheets to her chin and listened – it was a beautifully clichéd dark and stormy night, one that rattled the windows in their frames and caused draughts to lick across the skin in unseen malevolent caresses. For fear he’d go on a midnight wander, get outside and blow away like some pyjama-wearing woebegone Mary Poppins, she had even resorted to putting the chain on Gordon’s door. She’d hated doing it – she was supposed to be his nurse, not his keeper.

The only thing in the house that hadn’t felt it necessary to make its presence felt that night by rattling, creaking, clanking (or bizarrely pinging) was the chain on Gordon’s door. He seemed to be sleeping soundly, which wasn’t surprising given the heap of pills she’d been obliged to pile into him. In fact, he’d been unexpectedly compliant when she’d taken in his cocoa, sat with him and helped him to prepare for bed. He hadn’t even flinched when she’d cleaned the rug with white vinegar to neutralise the smell of pee, or batted an eyelid when she’d found the major source of the stench – the several vases that had been used as impromptu receptacles for Gordon’s urinary urges. Maura was sure that Moorcroft, Crown Derby and Minton had not intended their delicate and beautiful wares to be used for such purposes. Had they not been worth a small fortune she might have thrown them in the bin, but instead she’d borrowed Cheryl’s rubber gloves and had scoured them clean while praying she wouldn’t ruin them.

Sleep proved elusive and all she had done was toss and turn on the lumpy mattress, trying to find the sweet spot. The camphor was intrusive too, a particularly vile smell reminiscent of frugal old ladies and the bad old days. It reminded her of staying with her grandmother when she was little, of secondhand shoes and hand-me-down clothes, of having her face washed with carbolic soap and being expected to clear her plate because people were starving in Africa. It reminded her of the instruction to make do and mend, a philosophy she felt she was being forced to live by. How did you make do with nothing and mend a broken spirit? More to the point, how did you begin in a house that was so depressing it seemed to suck the joy out of everything?