Полная версия

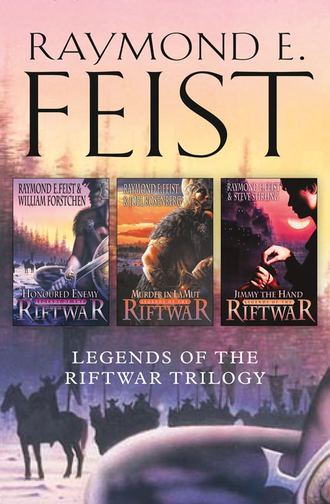

The Complete Legends of the Riftwar Trilogy: Honoured Enemy, Murder in Lamut, Jimmy the Hand

Roxanne looked around the room and then with a gesture of disdain, placed the front of the crossbow on the floor, recocked it, loaded another bolt in and slipped the weapon back under the seat. This gesture caused a redoubling of laughter and finally, looking a bit irritated, she stalked out of the hall.

‘Ahh, that’s my blood!’ Wolfgar roared. ‘That’s the type of women I can sire. By all the gods, I can still do it, I can, if only I could find a wench blind enough to let me!’

His comment caused a hearty round of toasts and cheers, Asayaga translating the boast to one of the soldiers sitting by his side so that it shot around the room, the laughter increasing as it spread to the other Tsurani. The few women in the room were also laughing, shaking their heads and holding their hands up in mock horror.

Wolfgar stood up, and with a groan somehow managed to step up on to the feasting table, knocking over a platter of meat. Raising his feasting cup, he drained it to the dregs, tossed it aside and slowly walked down the length of the table, acknowledging the upraised flagons and goblets and the lusty cheers of the men. A number of the Kingdom troops started into an obscene ditty about a blacksmith who had five daughters, and the fate that befell each of their midnight visitors who were dragged out to face the hot tongs and anvil. The Tsurani were singing as well. Somehow they had understood the nature of Wolfgar’s boasting, and Asayaga was intrigued that the song they started to sing in counterpoint had almost the identical plot.

Finally Wolfgar held out his hands for the men to be silent and the room fell quiet. As he stood the years seemed to fall from his shoulders. Dennis watched with approval, knowing that before them stood one of the Kingdom’s finest singers of sagas, even if he was a reprobate, liar, and thief.

Softly at first, but with firm control, the old man began a very old song:

‘Fare thee well, my sweet Kingdom lassie, Fare thee well, and I bid you goodbye, For I’m off with the dawning to cold northern mountains, Off to the north, where for King shall I die …’

Dennis sat back and looked over at Asayaga, who seemed intrigued by the old song of a soldier knowing he was sent to face the Dark Brothers in a campaign doomed from the start. Dennis closed his eyes and remembered when he had first heard the song as a boy. He had sat by his father’s side, silently listening to Wolfgar, while tears had flowed unchecked down his cheeks. The song was about duty, honour, and sacrifice, and Dennis wondered at Wolfgar’s choice. For if any Kingdom men were doomed to the fate of the hero of that song, it was the men in this room.

Asayaga saw Dennis’s expression, and realized the song had some meaning for him. He listened to the story in the song, ignoring its odd rhythm and strange tonal qualities. The story was heroic, about a man who put honour above common sense. Asayaga was torn, because on one hand, it was a very Tsurani attitude, yet on the other, no Tsurani would even raise the question of failure and debate it, even within himself. To die for honour was a great thing.

‘I’ve spent too much time on this world,’ he muttered to himself, as Wolfgar finished to a deeply appreciative round of applause. Asayaga saw that some of his own men had translated for the others, and more than one soldier on both sides sat with eyes rimmed with moisture.

Yes, thought the Tsurani Force Commander, it is a powerful tale.

He left the room, ignoring the bitter cold outside, and went to the slit trench he had ordered dug earlier in the day. The men had used the common area in the centre of the stockade when first arising, and he had put a stop to that as soon as he realized there were no latrine facilities inside the stockade. No soldier with any field experience would let his men foul their own camp. Disease came too quickly on the heels of filth, a point that seemed to be lost on the barbarians. He reached the trench and started to relieve himself, a sense of relief flooding through him.

‘They’re happy in there.’

Startled, Asayaga saw that Dennis was by his side, relieving himself as well. Finished, the two stood silent for a moment, the blizzard driving the snow around them. The lanterns hanging on the outside of the long house swayed in the wind, casting dim shadows, barely visible as a heavy gust of snow swept across the narrow courtyard.

‘We’re going to be stuck here for a while,’ Dennis said. ‘The only way out now is through the high passes and they’ll be blocked by morning.’

‘It keeps the Dark Brothers out, though, even as it keeps us in.’

‘Yes. The chase is over.’

‘For now at least. I doubt if they will give up. We’ve injured them. If it was reversed, Hartraft, if they were trapped in here …’ His voice trailed off.

‘No. If it was me and my men trapped in here and you were on the far side of the mountains, what would you do?’

‘Wait you out.’

‘I see.’

Again they were silent for a moment.

‘You are a hard man. A hard opponent, Hartraft. Were you this way before the war?’

‘That’s not your concern. What we face now is my concern.’

‘Our pledge to fight, is that it?’

‘Like I said, the chase is over. We agreed to a truce until we escaped, and for the moment we have.’

Asayaga turned and stepped closer until they were only inches apart. He looked up into Dennis’s eyes. ‘What do you want? Come dawn should we roust our men out from in there, line up, draw weapons and commence slaughtering one another?’

Even as he said the words both could hear the laughter and the start of another song from within the long house.

‘We both know what is in there is not real,’ Dennis replied, waving vaguely towards Wolfgar’s long house. ‘We’re outside our world for the moment, but sooner or later reality will come crashing back in. Less than a hundred miles from here, this night, Kingdom troops and Tsurani troops are sitting in their camps, waiting out the weather, and when the blizzard passes, they will be out hunting each other, and the war will go on. Are we any different, are we excused?’

‘We could kill each other tomorrow down to the last man and it won’t change what happens back there. I am as honour-bound as you, Hartraft, but killing you tonight will not change the war. It is as if we are both dead and gone from it. Tell me, is it honour, a sense of duty or vengeance which drives you now?’

Dennis did not reply.

‘Is it dawn then? If so, I’d better go in and tell my men to stop drinking and prepare. You’d better do the same.’

He snapped out the words, struggling to control his anger and stepped back. Then he bowed formally, and started to turn away.

‘Wait.’

‘For what?’

‘Just wait a moment,’ Dennis said, his voice heavy, distant. ‘There must come a day, we both know that. Once back into our lines, yours or mine, we have to face that.’

‘So why not now?’

‘Don’t press me, Tsurani: the ice we tread on is thin.’

‘Go on then, say what you want.’

‘We’ll still need each other once the passes clear. The Dark Brothers will be waiting, perhaps even bringing up reinforcements. We stand a better chance of surviving if we work together.’

‘Is that the real reason?’

‘Like I said, the ice is thin: don’t press me.’

Asayaga finally nodded.

‘A truce, then, till we return to our lines,’ Dennis said haltingly. ‘We command our own men, and keep the peace between them. If any break that peace, you and I agree to sit in judgement together.’

‘With Wolfgar.’

‘Why?’

‘I suspect he might be the most impartial of all.’

‘You’re right,’ Dennis replied slowly. ‘He will judge as well. We share all rations, lodgings and work.’

‘Of course.’

Asayaga looked back at the long house. ‘And the daughter – Alyssa, what of her?’

‘I don’t know what you are talking about!’ Dennis snapped.

‘Fine then.’

Dennis hesitated then extended his hand. Asayaga took it.

Neither noticed the intent presence that lingered in the doorway of the stable and had heard every word.

• Chapter Twelve •

Blood Debts

THE BLADE WAS SHARP.

The tip of the knife punctured his skin effortlessly, drawing forth a drop of blood. He watched the tiny pearl of crimson well up on his skin, and turned his arm so that the drop might fall free. He watched as it stained the icy whiteness beside his boots. The daily ritual complete, Bovai sheathed the blade.

His left arm was scarred from elbow to wrist by tens of thousands punctures he had inflicted upon himself over the years so that the limb was now a mass of twisted scars.

Soon, he thought, I shall be done with this ritualistic self-mutilation. Soon the stain on the honour of my family and clan will be finally ended.

On the night he had heard for certain that Tinuva had gone over to the eledhel he had vowed thus, to draw his own blood in atonement, day upon endless day, until the blood of the traitor was spilled.

For Tinuva, the traitor, was also his brother of birth.

Lowering his arm, he leaned back against a tree and looked down at the fortress guarding the river crossing. They had been camped there for nearly a fortnight, over three hundred of his brothers, the remaining humans and goblins crammed into the stockade, waiting for the weather to change and for his scouts to report that the northern passes into the valley were clear enough for his force to attack. The swirling snow lifted for a moment so that he caught glimpses of men coming back in from the forest, guiding a cart loaded with wood. He absently rubbed his scarred and bleeding arm and closed his eyes. There was a time, a time so long ago it seemed he could hardly remember it, when Tinuva had been his beloved brother, Morvai, spoken of by many as the one who would one day be the Paramount Chieftain of Clan Raven. Some even whispered that perhaps he would even be the one to unite all the clans in holy war, so that the exile in the northern bitterness would end and the plague of humans and the traitorous eledhel would be driven into the sea.

How he remembered those days, when together they would go out into the forests to hunt, to talk, to dream: two brothers still in their youth, side by side, planning for all that would come …

Morvai was fair to behold. Some would later say that from birth his heart was already calling him to join the eledhel. There had been a gentleness to him, rare in moredhel warriors, save when with their mates and young. Yet all would admit that none could match him in the hunt, in the skill he showed with blade or bow, in fleetness of foot, or even in the charm of his voice. And there was no doubt as to his fierceness and courage in battle. No small number of humans had died at Morvai’s hands, and a number of the eledhel, as well, before he had felt the unnatural tug of their queen’s dark magic.

As he remembered Bovai lowered his head, for he had loved his brother – idolized him – and would have gladly served him. His loyalty was remarked upon by all, and the sight of one brother without the other by his side was considered rare. Bovai knew that Morvai had abilities he lacked: a quickness of mind and a nimble wit. So he attempted to achieve what his brother had with different tools: strength and cunning, ruthlessness and an unhesitating willingness to kill. Together they were a perfect pair, the blade and the hammer. What Morvai could not achieve with guile, wit, and charm, Bovai could achieve with brute strength and terror.

So they had been for the seemingly timeless years of their youth. They had faced a hundred battles together against rival clans, renegade humans, even venturing beneath the earth to take the riches of the burrowing dwarves. Each had saved the life of the other more than once, and as he contemplated the memory Bovai’s hand drifted to his chest, to the wound he had taken leaping in front of Morvai so that the arrow had struck him instead of his brother.

How Morvai had wept that night, sitting by his brother’s side as the bolt was withdrawn. He had pledged his undying devotion and had cut his own arm, letting his blood drip into the wound so that their bond was seen by all to be eternal.

There are few things that could break such a bond, but at last they had encountered it and her name was Anleah. Bovai remembered as if it were days before instead of years …

The brothers had watched in open admiration as Gaduin, their father and second most powerful chieftain of the clan, returned in triumph. The warriors following him carried booty and led half a dozen prisoners with their hands tied behind their backs. One of them instantly commanded attention.

She was beautiful and proud, and no warrior looking at her for a moment would fail to recognize her for what she was: the daughter of a chieftain. Bovai and Morvai stood before the entrance to their father’s home, their faces stoic masks, but their eyes shining with pride.

‘My sons!’ Gaduin had called to them. ‘See what I have fetched home. She is the daughter of our old enemy, Vergalus of Clan Badger, and she will be our guest for a while.’

Their father had given her over to the women of the lodge to be cleaned up and made presentable, and she had dined as a guest at their table that first night.

She gave her parole not to attempt escape, or accept rescue, and was therefore allowed to live under their roof, and was given the freedom of their village. Both brothers were taken by her beauty, the soft charm of her voice and sharp intellect. She had seemed perfect to Bovai …

From the moment he had laid eyes upon Anleah, Bovai was smitten, though he had no tongue to tell her, or his father. It was Morvai, the elder brother, who had always had the knack for smooth words and finely-turned phrases, who had pressed his suit.

Morvai spent as much time with Anleah as was possible, and Bovai retreated deeper into his silent longing for the girl, until the night when Morvai had asked their father to intercede with Murad, not to return the girl to her clan, but rather to send gifts and seek permission of her father for Morvai to take Anleah for his wife.

Gaduin had laughed and revealed his true intent in leading the raid and taking her prisoner. The bitter rivalry with Clan Badger had consumed the two clans for decades and scores of the best warriors on both sides had died. It had always been Gaduin’s hope that Morvai would find her becoming, and take her as wife.

She was too young to rule and had no brother, and no chieftain in Clan Badger held enough power to hold that clan together once her father joined the Mothers and Fathers in the next world. Murad had no offspring, though he had numbered three wives over the years. Gaduin saw his eldest son as the logical inheritor of the Paramount Chieftain’s mantle some day, and knew that with Anleah as his wife, the two clans would eventually be joined. Thus peace would be established, and the strength of Clan Raven doubled by the alliance, with the possibility of Clan Raven eventually absorbing Clan Badger under the rule of Morvai, and after him the children of his union to Anleah. With two of the greatest clans in Yabon united, the process could begin for the taking of the others.

And it was clear at that moment to Bovai that he must stand aside and remain silent. He feigned delight at his brother’s happiness, and said nothing when his father dispatched an embassy to Clan Badger proposing the truce and to negotiate a bride price.

Bovai accepted this out of love for his brother, though it burned his heart. What burned even more was that Morvai was so taken with Anleah’s charms that he never realized the anguish this caused his brother. So Bovai forced his gaze to look elsewhere when Anleah walked past, averting his eyes when she ate at their table, struggling not to notice the scent of her hair, the dark flicker of her eyes, the power of her voice.

Less and less did Morvai go to the hunt with his brother and a strain developed between them. Days would pass when they barely spoke and he tried to believe that it was because Morvai had begun his courtship: a series of rituals that could take years before he and Anleah could come together at last. Bovai feared that his brother suspected Bovai’s hidden longings, and so the estrangement became mutual. Later, Bovai realized the odd distraction Morvai had shown had nothing to do with his betrothal to Anleah or to any concern over his brother: rather it was the first stirring of that cursed pull from Elvandar – what the eledhel called ‘the Returning’.

Days passed into weeks, and Bovai lived on a diet of pain and longing. Then one day, Gaduin announced the betrothal of Morvai and Anleah with the plan that they would be married on Midsummer’s Day.

Six days before Midsummer’s Day, the entirety of Anleah’s family, complete with retainers and warriors of note, arrived for the wedding rites. Bovai found it strange to be surrounded by warriors of Clan Badger, since he recognized more than one from fights of old. In their midst was a warrior whose countenance bore bitterness and gloom, and his name was Kavala. While others in his clan seemed pleased at the marriage and the forging of a bond between the clans, Bovai knew that this warrior regarded his brother with a special hatred. For if any warrior in Clan Badger was likely to follow Vergalus as Chieftain of Clan Badger, it would be Kavala. Yet he saw the future as clearly as a hunter saw a buck in a clearing. Should this wedding go forward, he would some day have to bend a knee to Morvai and swear allegiance.

In addition, years before, in one of the many skirmishes between Badger and Raven, Morvai had killed Kavala’s brother. Bovai knew that Kavala had one more reason than he needed to hate Morvai.

The reception of the Clan Badger warriors and the family of Anleah was cool at first, but by the end of the evening toasts were raised by both sides, pledging the end of hostilities, and both Gaduin and Vergalus were open-handed in the paying of blood-debt gifts to the fathers, brothers and sons of warriors slain in battles of old, those who had not yet been avenged. Kavala had been tight-lipped, but he had uttered the ritual words as Morvai presented him with a finely-fashioned bow of yew and bone as a debt-payment for killing Kavala’s brother. No hint of forgiveness was evident, but he observed the formalities. Thus was the feud ended.

While this ritual was going on there came a moment when Bovai saw Morvai alone and he approached his brother’s side.

The look in Morvai’s eyes was one of warning.

‘If you come to tell me that you love her, I know,’ Morvai said evenly.

Stunned Bovai could not reply.

Morvai put his hand upon his brother’s arm. ‘You have acted with honour.’ Then he spoke softly. ‘The heart wants what it wants. Always remember that, no matter what else happens.’

Bovai found he could not speak. And then Morvai turned away, broke into a smile and extended a hand to his bride’s father, and the two of them clasped hands firmly, then shared a drink from the same goblet.

Bovai had looked over at Anleah, seated at the feasting table and, seeing her aglow with love for Morvai, had felt his heart might shatter within his chest, for he knew that he would never see her look at him in that way.

Throughout the ceremony he had stood by his brother’s side, heart filled – at first – with pain, but when he had seen his brother kiss her, he had forced his mind away from his pain, and willed his heart to ice. He would never love again, if love meant such pain.

He had seen something else at that ceremony: the look she gave to Kavala. It had been warm – a friend’s smile – yet the look Kavala had returned to her told Bovai that now Kavala had three reasons to hate Morvai. He saw a reflection of his own longing mirrored in Kavala’s expression, just for an instant, only a brief flicker; but Bovai had seen it.

When, at long last, protocol permitted, Bovai fled, leaving the feast for fear that his stomach would rebel and that he would vomit. His pain drove him from the camp. He took his bow and told a sentry he was going hunting.

For five days he absented himself from his father’s compound.

For a year and a month, Bovai and his brother lived without comment. Anleah grew more beautiful, happy in her marriage. Every smile and laugh was a dagger in Bovai’s heart, for he knew the laughter and the smiles were for Morvai. She loved him with an intensity only a few of the moredhel ever knew, and even the most reticent among the warriors would smile at the sight of her singing on her way to the stream to clean clothing, or as she tended the garden.

But Morvai grew more reflective, more thoughtful, and disappeared alone in the forest for days at a time, often returning without game. There were days when he would suddenly become distracted while in conversations, as if he were listening to some distant call.

One day Morvai called Bovai to his side and said something that troubled his brother for months to come. ‘Should I fall, brother, should anything happen to me … will you look after Anleah?’

Bovai said, ‘Of course, but nothing will happen.’

Morvai smiled and said, ‘Fate is fickle, brother. Rest assured, something will happen.’ He put his hand on his younger brother’s arm. ‘See to her needs. Take her back to the lodge of her father, should that be her wish.’

‘I will,’ said Bovai.

Months fled, the seasons passed, and Morvai became ever more distracted. Gaduin asked Bovai if he knew what troubled his eldest son, but Bovai could think of nothing. Yet Bovai also sensed a deepening unease within his brother’s soul.

Then, in late summer of the third year following the marriage, Morvai finally changed. No moredhel needed to be told when a family member made the change, known by the eledhel as the Returning. Bovai awoke an hour before dawn one day with a dread sense that something was terribly wrong. He was already out of his bed and in the courtyard of the compound, buckling his sword-belt, when he heard Anleah scream.

He had raced with his father and other warriors to Morvai’s lodge, and inside found Anleah standing before an empty bed.

‘What is it, woman?’ Gaduin shouted.

Softly, with tears flowing down her cheeks, Anleah spoke. ‘I awoke to find a stranger in this room, father of my …’ Her voice broke. ‘My husband is no more.’

A cold more frigid than ice stabbed through Bovai’s stomach. He glanced at his father and saw the old warrior’s implacability. While his mask remained in place, all colour had drained from his cheeks.

Softly, Gaduin said, ‘We must find the traitor. He must die.’

Bovai felt the same pent-up rage and fear that his father was suppressing. Their beloved brother and son had changed. He was no longer of their blood. The evil Queen of Elvandar’s black arts had lured away another of their people: even as they stood there, the being who had once been Morvai was making his way southward, toward the haven of Elvandar.

Bovai signalled and warriors hurried back to their own lodges to get weapons. Within minutes, fifty moredhel had made their way into the forest, after Morvai.

The chase had been brutal, with no respite for either prey or hunters. In the memory of their race, there had been no greater affront to a clan than this. Even those renegades who had been banished by their own people and who lived in communities of humans and goblins might some day redeem their honour. But one who fled to Elvandar was a betrayer of everything that made one a member of the People, a moredhel.

For six days they ran through the forests, swamps and bogs of Yabon. At last they came to the river marking the boundary of Elvandar.

Bovai had glimpsed his brother three times in the chase; once upon the crest of a hill, another time moving into distant trees on the other side of a valley; and there at the river’s edge.