Полная версия

The Men Who United the States: The Amazing Stories of the Explorers, Inventors and Mavericks Who Made America

This belief had helped propel Jefferson into his seat in the Continental Congress. And his unwavering devotion to its principles led to his sponsorship, a decade later, of a new law, the practical effect of which can be seen nowadays in just about every American town and city beyond the East Coast and on just about every field west of the Ohio River. This was Jefferson’s Land Ordinance of 1785—An Ordinance for Ascertaining the Mode of Disposing of Lands in the Western Territory—a piece of legislation that laid down the rules for how the immense tracts of new American countryside, at the time neither owned nor properly known, were to be described, divided, and eventually distributed.

Though a dreamy Jeffersonian idealism lay at the legislation’s heart, this prescient and profoundly significant piece of legislation not only provided land for those who wished to own it, but also raised money for a new government that was financially exhausted and depleted by the war with the British. The western lands were the new nation’s greatest physical asset—albeit an asset taken without regard for the Native Americans who inhabited them. The new government could sell these lands, in parcels, to anyone who had the wherewithal to buy them. So Jefferson’s ordinance set out principles for creating the parcels. Most crucially, it laid down the requirements for a survey, for the creation of a grid of meridians and baselines from which to create these parcels.

To start the process, there also had to be established a place where the surveys of western America would be formally begun, a place that was then touchingly named, as it remains named today, the Point of Beginning.

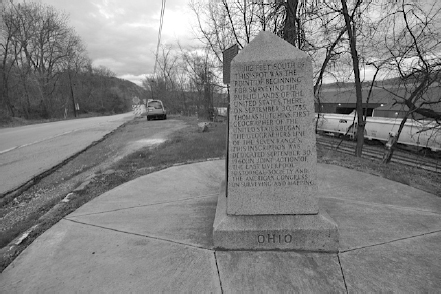

The honor of locating this point went to Ohio—or what would later become Ohio, the crucible of the Old Northwest. The point can still be seen today, just. It is on the outskirts of a grimy industrial town called East Liverpool, close to a family firm named S. H. Bell, which processes, crushes, and screens, as well as stores and ships, many of the basic materials of the country’s industrial lifeblood—bricks, wire, cement, oil-fracking sand, pig iron, steel billets, fertilizer, and limestone. Here, at the point where Pennsylvania becomes Ohio—and 1,112 feet north of where, a few score yards out into the river, a slim tongue of West Virginia licks its way between—is the monument which, though it doesn’t exactly say so, truly is a memorial to these two most Jeffersonian ideas, private land ownership and public westward expansion.

From near this unlovely spot, beside a railroad line and an industrial storage yard outside East Liverpool, Ohio, all of western America is still measured. The obelisk marks the Point of Beginning, the origination site for the meridian and baseline used since the first surveys of the nation.

It is a cement stele, about chest high, sitting on a circular stone mat on which are engraved the four cardinal compass points. The monument is a four-sided obelisk, not unlike the very top of the Washington Monument, with suitably portentous inscriptions on each side. Few of the motorists hurtling by on state highway 39 bother to stop to read, even though the obelisk is surrounded by a small copse of other cast-iron markers and stone boundary posts, and by rights it should be most alluring. It is indisputably one of the more historically significant sites in the nation, a place that should have tour buses and fountains of cool drinking water, even a souvenir stall. Instead it sports a scruffy parking space, one forlorn utility pole, and a scattering of litter.

Jefferson’s name is not there; instead the marker notes that “On September 30, 1785, Thomas Hutchins, first Geographer of the United States, began the Geographer’s Line of the Seven Ranges.” Mr. Hutchins was very much Thomas Jefferson’s man, a keen supporter of the distant vision of the American West as an immense “empire of liberty.” He was a soldier, a cartographer, and the architect of a system of surveying that continues to be employed in America to this day.

Taking this arbitrary spot as his starting point, he drew lines—one north and south, the meridian; another at right angles to it, the baseline. Once having determined, with the use of sextants and star charts and chronometers, the precise longitude and latitude of the site—40° 38′ 33″ North of the equator, 80° 31′ 10″ West of Greenwich—he then set off with his rolls of twenty-two-yard-long iron Gunter’s survey chains,1 then later with his theodolites and compasses and plane tables, and his party of army-protected cartographers, to survey America.

And by America, Hutchins meant the entire continent, though at that time the nation extended only to the Mississippi River, the boundary with the lands then owned by Spain. For the baseline, that magical arrow-straight line at 40° 38′ 33″ North, known to this day as the Geographer’s Line, was by law decreed to extend westward through “the whole territory,” all the way to the Pacific Ocean. America might not yet have title to all of the lands between the Ohio River and the Pacific, but now that it had a baseline computed, it was not entirely fantastic to imagine that one day it might.

This was Jefferson’s dream, after all. Now that his ordinance was firmly a part of the nation’s law and the survey well under way, he made a famous remark: that despite his young country being hemmed in by lands in the north still belonging to Britain, by lands in the south belonging to Spain, by territories in the near west under the vague control of often hostile aboriginals, and by lands in the farther west controlled by France, “it was impossible not to look forward to distant times, when our rapid multiplication will expand itself beyond those limits, and cover the whole northern, if not the southern continent, with a people with similar laws.”

It was certainly not fully anticipated that a cash-strapped Napoléon would ever actually sell the land he called Louisiana—let alone that he would sell all of it and all at once. At the time of the survey’s beginnings, no one except Jefferson thought much beyond the coming months. Settler life was precarious, and even policy makers tended to think in seasons, not decades, their business more concerned with planning for harvest than for history.

Some say Mr. Hutchins invented the survey system under which he worked, which has endured as a model for many of the world’s great surveys. It called for the creation of townships, six miles square, stacked north and south in what were called ranges. Each township was divided into thirty-six numbered sections of one square mile each (640 acres). The sections were divided into half sections (320 acres), quarter sections (160 acres), and quarter-quarter sections (40 acres), which led to such phrases as “the lower forty” and “forty acres and a mule.” This system—ranges, townships, sections, and subsections—is now woven deep into the fabric of modern American life, the basis for everything, a systematically numbered2 design for almost the entire nation.

It was intended that the distribution of the territory begin at a great clip. Sales offices were promptly set up—the main center being in the nation’s capital, New York City—where petitioners put down their money (a dollar an acre minimum, no land sold on credit) and walked away with a title document. The results of the plan and the purchases can be seen today on any map—Western farm after Western farm regularly spaced and perfectly aligned beside undeviatingly die-straight roads spearing east and west, north and south; the country towns with their impeccable grid patterns of streets laid out from North Dakota to Arizona, from Oregon to Alabama; the siting in each township of schools (usually in section 16, with one in section 36 added later), town halls, courts, and railway stations; and the government’s retention of some sections (8, 11, 26, and 29) for future sale, the lawmakers in the capital believing, optimistic always, that once the township had been developed, the value of that land would skyrocket.

Matters in fact began rather hesitantly. The ordinance came into formal effect on May 27, 1785, and Hutchins began his survey of the first seven ranges of Ohio—the tract of land spanning the first forty-two miles west of the meridian—a scant three months later. But then scouts reported that a Delaware war band had attacked settlers some miles ahead—a trading post had been sacked and a migrant American murdered, his doorway smeared with red paint as a warning. Already the local indigenes—Shawnee especially—had expressed reservations at Hutchins’s plans. To add to their quite understandably cynical attitude toward white men’s treaties, and to their pervasive and quite reasonable fear of dispossession, they felt little sympathy for the settlers’ apparent need to draw straight lines through lands across which they had been content to meander for centuries, following the routes of animals and streambeds and other natural features. They welcomed the haphazard and felt slighted by the straight.

Hutchins’s surveying team was understandably spooked by the killing, and all pulled back to Pittsburgh. It took them nine more months—and a guarantee of cavalrymen’s protection—before they recovered their nerve. They then picked up their chains and came back, extended their 40° 38′ 33″ baseline to a town called Magnolia, and soon managed to survey with a fair degree of accuracy four of the ranges in 1787. By the next year, they had completed all seven.

The surveys were done hastily and often quite imperfectly; each section was merely marked with a white stone at its corners, and at first no surveys at all were performed inside the sections themselves. But it was a start. Congress was formally notified. Maps were then published, and the selling of America began, formally and in earnest. Tacked to office doorways and trees and published in such local newspapers as then existed were advertisements displaying the beginnings of a new phase in American history. Each showed a map

of the Seven Ranges of Townships, being part of the Territory of the United States, NW of the River Ohio, which by a late Act of Congress are directed to be sold.

That part which is divided into sections or tracts of a mile square will be sold in small tracts at public auction in Pitsburg the residue will be sold in quarters of Townships at the seat of Government.

During the next few years, all of the rest of the Northwest Territory was surveyed, and the salable sections were duly disposed of. Towns and villages and hamlets were born where the land was deemed most suitable for settlement, and thousands of hopeful migrants streamed westward. Within fifteen years, the quarter-million square miles of the old territory had been transmuted into the five-and-a-bit states that now occupy its immensity: Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and a part of Minnesota. Independent America had started out with thirteen states; now the constellation of stars that was symbolizing them on the nation’s newly adopted flag was starting to swell, and fast.

The more westerly of these states (Minnesota aside) stopped short where the territory had stopped short: the east bank of the Mississippi River. Beyond the cliffs and mudflats of the river, the writ of America did not run. West of the Mississippi, the land still belonged to France, and in theory and law, it was no business of Americans to travel there, either to survey or to settle.

Except that everything changed on April 30, 1803, when the American government—in what many consider the most prescient triumph of Thomas Jefferson’s presidency—bought from France all 820,000 square miles of its possessions on the American continent.

With a few strokes of a pen and the payment to Napoléon, America overnight doubled her size. With the acquisition—for $3 million in gold and $12 million in bonds—the country turned herself into what seers of the time recognized as a potential world power and even at that very moment a force to be reckoned with. The Louisiana Purchase, as the transfer was known, suddenly untangled America from the most pernicious of colonial snares and guaranteed her (because the port of New Orleans—Louisiana’s third and final capital city, after Mobile and Biloxi—was naturally a part of the sale) unencumbered access to the Gulf of Mexico. Included were seemingly unending stretches of real estate for the settlement of many more millions of yeoman stock—men and women who could be encouraged to undertake their advance from the rigors of respectable Eastern poverty to the nobility of hard-won Western wealth.

If this great tract of land earmarked for Jefferson’s imagined millions of settlers was to be properly incorporated into a United States of America—if, in short, it was to be united with all the existing rest—it all now needed to be surveyed and sold, just as the Northwest Territory had been surveyed and sold in the years before. To be surveyed and sold it needed also to be known. To be known, it needed to be crossed.

PEERING THROUGH THE TREES

The decision to cross the continent had actually been made some months earlier, on a late-summer afternoon in 1802 at Monticello. Thomas Jefferson was sitting in rapt attention, poring over a thick, heavy book of more than four hundred uncut and untrimmed pages, bound in blue paper and published by the firm of Cadell and Davies in London. Voyages from Montreal to the Frozen and Pacific Ocean had been written by a Scottish fur trader, from Stornoway in the Scottish Outer Hebrides, named Alexander Mackenzie. Or more accurately, Sir Alexander Mackenzie—since King George III had awarded him a knighthood for becoming the first white man ever to cross the entirety of North America.

Mackenzie had completed his voyage almost nine years earlier. He suspected that his seven-month overland journey to the Pacific was probably of historic moment, and so he had left a memorial. He had created what he hoped would be a lasting inscription on a tiny sea-washed rock near the present-day British Columbia fishing village of Bella Coola: “Alex. MacKenzie, from Canada by land. 22nd July, 1793.” He had inscribed the message with his finger, using an old trappers’ trick for long-duration messages, dipping it into a poultice made of bear grease mixed with vermilion powder and smearing out words that he hoped would survive the cold and lashing rains for which the Pacific coast is notorious.

One can imagine Thomas Jefferson’s reaction as he read the closing pages of the blue-bound volume, on learning that a mere Canadian, a British loyalist, had been the man to first traverse the American continent. It was unseemly. It was an affront. It was a claim that simply should not be allowed to stand.

As legend has it, he put down the book, his face purple with apoplectic annoyance, and turned to his twenty-eight-year-old secretary, Meriwether Lewis, who was sitting beside him. He told Lewis in no uncertain terms promptly to organize an expedition to cross his own country—an expedition that would, among other things, trump the ill-considered wanderings of a forelock-touching Scotsman. He had little reason to suppose the venture would in time become and remain, to all Americans, the most noted of all the many exploratory journeys through and around their now mighty, sprawling, and mysteriously alluring new nation.

This Monticello moment was the birth of the so-called Corps of Discovery, the United States Army’s expedition best known today by the names of its joint leaders, Lewis and Clark.

Meriwether Lewis himself needed little by way of convincing. He was not just curious and eager to match and better Mackenzie’s achievement, but he, like Jefferson, wanted to ensure that the detested British in no way preempted any potential American claims to the distant West. Lewis also had a highly personal motive to mount a new expedition, stemming principally from having been thwarted by Jefferson in a bid a decade earlier to try such a venture.3

Now, ten years on, Lewis was being asked to go. And to go, moreover, as the expedition leader—Jefferson being by now fully familiar with his assistant’s practical abilities as a trapper and hunter, a man who could travel far away in extreme discomfort and not come whining home. The president also admired him for being an exceptionally quick study—his “luminous and discriminating intellect” being one of the many reasons that prompted Jefferson to employ Lewis at the White House in March 1801.

Another reason Jefferson decided to order him out west was Lewis’s unusually sympathetic awareness of America’s aboriginal people. Lewis already had firsthand knowledge of various Indian tribes: the Cherokee in Georgia, where he had lived as a young man; the Chickasaw and the Shawnee when he was stationed as a soldier near modern-day Memphis; the Miami when he was involved in the mighty Battle of Fallen Timbers in far western Ohio; and later the Potawatomi near his army camp in lands close to today’s Detroit.

At the time of Jefferson’s pouting decision, the Louisiana Purchase had not yet been consummated. The drapeau tricolore still flew on the far side of the Mississippi. There was also evidence that maybe Britain was about to make some kind of claim on the territory too, leading to a certain urgency. Lewis had to leave, it was decided, and in double-quick time.

The depth of ignorance of the soon-to-be-acquired territory was profound. Its precise borders were unknown, for a start—and the French had made it abundantly clear they were not going to give Americans any information about them. Lewis and the party he would choose would have to start essentially from scratch. Where were the land’s natural frontiers, where were the mountain ranges, and how exactly did its rivers twist and turn down from the hilltops to the sea? They would have to find out. Moreover, were there truly, as stories of the time suggested, great peaks out in the vastness that were made entirely out of salt? Where were the territory’s snowfields, its deserts, the pastures and the prairies? What kinds of flowers and trees grew there, and what species of animals, which types of birds?

And who exactly were the peoples—the Indians, as Columbus had supposed—who had belonged to the land before? Was it true, as some said, that many of them were Welsh? Or, according to others, the Lost Tribes of Israel? And whoever they might be, where did they now live and have their being?

By March 1803 the necessary congressional authorization for the venture was in hand. A sum of $2,500 was appropriated—with $696 set aside for gifts to the natives. A month later and the transfer papers were formally signed in Paris, and the land that had so intrigued Jefferson was now fully American owned and so could be legally explored.

Lewis, now certain the expedition was to begin, procured a note of limitless credit signed by President Jefferson himself as a guarantee, just in case they ran out of cash. He then began assembling his gear. He found his rifles at an army arsenal in Virginia. He found builders for an iron-framed fifty-five-foot wooden keelboat in Pittsburgh. He found his ammunition, his trinket gifts, and his comestibles in Philadelphia. He had to imagine what else he might need: mosquito nets, waterproof lead tubes for holding ammunition, various bibelots and silver medallions struck with Jefferson’s profile to be handed out as marks of amity to the encountered Indians, large quantities of powdered ink, 193 pounds of dried soup, twenty-five axes, and four gross of fishhooks. He also took instruction in field medicine—mainly from a doctor of somewhat crabbed views who believed most ailments could be cured by powerful laxatives, especially one made of mercuric chloride and a ground-up Mexican purgative root named jalap.

With the gear assembled, it was now time to gather the men. In June, shortly before the secretary of war gave formal authorization on July 2 for the corps to select volunteers for the expedition from any of his army garrisons along the Ohio, Lewis wrote to his old army friend William Clark, offering him the position of joint leader of the expedition. The latter accepted cheerfully: “This is an undertaking fraighted with many difeculties, but My friend I do assure you that no man lives whith whome I would prefur to undertake Such a Trip.”

Clark was four years older and, in their previous encounter, had been the senior officer. Clark was more rough-hewn and both less literate and by all accounts less given to dark moods than Lewis. Clark had been tested in battle with Indians, while Lewis had not. And Lewis was very much Jefferson’s protégé, while Clark had barely a nodding acquaintance with the president. Nevertheless, the pair—who joined up in the Ohio River town of Clarksville, Indiana, in October to begin their formal collaboration—got on famously well on just about every day of the 856 they would spend away together.

In Clarksville they assembled their full team, the soldiers chosen from the scores of fort-weary volunteers ready for an opportunity of real excitement. In the end some twenty-nine men, including Clark’s slave, York, were sworn in for the duties ahead.

There were ten weeks of training and preparation before the team was prepared to start. History records with some precision the formal beginning of the expedition: three thirty in the afternoon of Monday, May 21, 1804.

By now the winter was well over; the ice was gone, and the rivers were brimming with snowmelt. Having crossed the Mississippi separately, Lewis rejoined Clark some slight way along its principal tributary, the Missouri. The place he chose was the village of Saint Charles, a threadbare settlement on the river’s north bank with a population of about four hundred, most of them French Canadians.

There was a simple topographic reason for the choice of the expedition’s starting point. Close to the junction of the two streams, there was a mess of fluvial indecision, with the tributary rivers swiveling direction at the behest of their conjoined currents, leaving a maze of swamps and oxbow lakes and blind-alley bays all across the landscape. But in Saint Charles, the Missouri seemed at last to start pulling itself firmly away to the west—the direction in which the expedition wanted to go.

The river’s course was directed by the local geology—the same geology that also enticed the first settlers. There was a low bluff of Devonian sandstone hills on the river’s northern bank, the first elevated ground west of its junction with the Mississippi, which would both keep any settlers safe from floods and, in case of attack, offer their pickets a good view of the waters downstream. So a cluster of buildings was built along the bluff—a Catholic chapel, a hundred poorly made houses, a few shops. All of them looked southward across the deep brown stream—the Big Muddy, as it would later be widely called (Clark claimed to find a wineglassful of ooze in every pint of Missouri river water)—toward the scattering of houses in distant Saint Louis, toward the familiar and the known.

Behind, beyond their village pale, was the true unknown—a terra incognita of brown Indian hills, expanses of lands unfamiliar and potentially hostile. Hunters and trappers ventured there—but no settlers, not yet. Saint Charles was thus for many years the most westerly European settlement, the last bastion of immigrant civilization, a town that lay at the very point of intersection between settled America and untamed native lands of the frontier. It could scarcely have been more appropriate as a departure point.

A thunderstorm was raging when Lewis arrived from Saint Louis. He took what churchly men still charmingly called a cold collation—a snack, allowed on fast days—and then crossed the river, where he found Lieutenant Clark and his party encamped for the evening. Most of the party (except for one member, who the night before had received fifty lashes for going AWOL and then displaying “behavior unbecoming” at a party) were “in good health and sperits.” Small wonder: Clark had been royally looked after during his four-day stay: the local Gallic swells offered far better food and wine than had ever been available back east, together with invitations to balls and visits to his boats by numbers of ladies of the town.