Полная версия

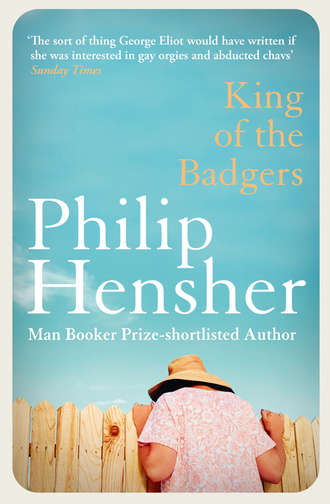

King of the Badgers

The security and handsomeness of the estuary town drew outsiders. It also, less admirably, persuaded those outside its historic boundaries to appropriate its name. Some way up the A-road towards more urban settlements, there were lines of yellow-brick suburban houses, a golf club, a vast pub on a roundabout offering Carvery Meals to the passing traffic on a board outside. In its car park feral children romped, and, fuelled on brought-out Cokes and glowing orangeades, ran up and over the pedestrian bridge across the A-road. They had been known to shy a half-brick at lorries passing below. There was an extensive and spreading council estate on either side of the traffic artery, surrounding the Hanmouth Rugby Club grounds; it provided a flushed and awkward audience to the field’s gentlemanly battles, over a leather egg, mounted for an afternoon, a drama bounded between two dementedly outsized aspirates.

All these things, encouraged in the first instance by estate agents, had taken to calling themselves Hanmouth too. They, however, called it Han-mouth, to Hanmouth’s formal scorn and comedy. It was one of Miranda Kenyon’s conversational set-pieces, the speculating about where the boundaries of Hanmouth would end. On the whole, Hanmouth thought little of the despoiling and misspeaking suburbs that surrounded it and had taken on its name. Though they poured right up to the gates of Hanmouth, they were obviously the city’s, Barnstaple’s, suburbs, not Hanmouth’s. Hanmouth could never have suburbs.

In these suburbs and estates, men washed their cars on a Sunday morning; kitchens faced the front, the better for wives doing the washing-up to watch the events in the street; children kicked footballs against the side of parked cars until bawled out; support for local or national football teams was made evident in displayed scarves, emblems stuck in windows, flags flown from the back of cars; and, at seven thirty or eight o’clock on weekdays, a ghostly unanimous chorus of the theme tune to a London soap opera floated through the open windows of the entire suburb. There was no reason to go there, and Hanmouth knew nothing much of these hundred streets. It was in the early summer of 2008 that an event in these suburbs, whatever settlement they could be said to belong to, rose up and attached itself to Hanmouth, and could not be detached.

3.

No one in Hanmouth proper had ever heard of Heidi O’Connor. Unless she cut their hair, and then they still wouldn’t know her surname. She did her shopping where no one hailed each other or equably compared purchases, in the Tesco’s on the ring-road. She was not one for going to the pub for social reasons or any other, even to the roadhouse on the Hanmouth roundabout. She would have said she found it ‘common’, a word most of Hanmouth would have been astonished to discover a Heidi O’Connor knew or attached any particular meaning to. She had four children, Hannah, China, Harvey and Archie, from nine down to eighteen months. She lived with Michael Thomas, a moon-faced reprobate seven years younger than her. The four children, two with a version of Heidi’s white-blonde hair, two with a dark, thick, doglike scrub on top, were said to get on with their ‘stepfather’, as Micky Thomas generously termed himself when events made a definition necessary. He was the third such ‘stepfather’ the children had known and the eldest two could remember. Only Hannah could remember, or said she could, her proper father and China’s.

With four children at twenty-seven, Heidi’s existence had its circumscribed aspects. She rarely went into Barnstaple—the opening of a new shopping centre represented an unusual outing. She and Micky and the four kids, walking up and down the glass-covered streets of the mall where municipal jugglers and publicly funded elastic-rope artists played with the air for one afternoon only. Here and there, Heidi and Micky said to each other that it was nothing special, really, letting the kids run in and out of the shops. Barnstaple, in general, was Micky’s territory. He went in every Friday and Saturday night; he stayed out till three or four, returning huge-eyed and off his face, as he would say the next day. Saturday afternoons he spent in Hanmouth’s pubs, often drinking until it was time to pick up Heidi from the salon. He waited outside on the pavement for her; he’d had to be spoken to sharply about coming in and wandering about before half five, picking up bottles of conditioner and tongs and putting them down again. He was a familiar figure in Old Hanmouth, as he called it; he was a well-known figure at the edges of the dance floors of the little nightclubs of Barnstaple, his moon face expressionless under a CCTV-defying baseball cap. He would often sell you a little bit of this, a little bit of that.

Heidi thought herself too old for that sort of thing. She spent most of her time indoors when she wasn’t working at the hair salon in Hanmouth, where most of the customers were over seventy, but all right, really. She’d always said at school she wanted to be a hairdresser, and though Hannah and China coming unexpectedly had interrupted the HND, she’d made an effort, bettered herself, finished her course when she was twenty-two, and got a job here, where she worked now. Her dream was to open up a salon of her own, she said; maybe even in Hanmouth. It could do with some competition, something a bit more up-to-date. A bit less blue-rinse, she would say, though she hadn’t done a blue rinse in her life, only heard of them on comedy sketches. ‘I don’t know how she stands them,’ Micky would say to his mates and his associates when Heidi was in the kitchen, talking about the widows and retired woman civil servants of Hanmouth. ‘Them old punters. Smelling of wee and asking for your blue-rinse perm.’ Heidi herself didn’t mind them, or Hanmouth. She didn’t think too much about it. The pay could have been better, but the tips were generous, and it got her out of the house. Micky made money in his own ways. Those own ways came and went, but were a useful backup at any rate. And every Wednesday and Saturday they played the lottery. If you asked them what their ambitions were, they would both have said that they aimed at a future where an exponentially large sum of money landed on them, unearned and undeserved, and proved inexhaustible, however long the pair of them lived. It was sweet that they didn’t seem to think, for the moment, of a future where undeserved and enormous money would rid them one of the other.

Her childhood sweetheart she’d never married, though he’d given her Hannah and China, and he might be in London by now. Harvey’s dad was the one she’d married, and never again. At the end, in the middle of one of those staircase-shaking rows, he’d said he was going to emigrate, to Australia or Canada, and had gone on saying it, with varying degrees of calmness or rage, until one day he’d just disappeared, never to be seen again. (Heidi supposed she was still married to him, all things being considered.) His name was Marcus. She remembered what he looked like, but what had really remained with her from that marriage was Harvey, of course, and Marcus’s half-sister Ruth—they’d had the same father, but Marcus’s mother had been from Bristol, Ruth’s from Barnstaple. The father was where they’d got the black half from. There were fifteen years between Marcus and Heidi, thirteen between Marcus and Ruth. Ruth had always been the same stern-looking girl with cropped hair touched with grey, though she was only two years older than Heidi. At the wedding, with Hannah only just old enough to be a little bridesmaid in peach, China still a baby in Heidi’s mother’s arms with a terrible rash across her face, Ruth’s constant frown hardly cracked. Some old uncle of Heidi’s with a red carnation in the buttonhole of his grey suit and the red-veined nose all Irish drinkers got in the end had leant over to Heidi’s mother and said he was a handsome lad, but he, he was old-fashioned, he supposed, and thought it a shame, his lovely niece who could have had her pick marrying a half-caste like that. And Ruth had abruptly turned round—people said, ‘So she turned round and said,’ but Ruth really had turned round, as swift as a whip in flight—and said, ‘That’s my fucking brother you’re talking about, you stupid old cunt. His name’s Marcus.’ There was no answer to that. The old uncle, who had only been invited because Heidi’s mother was soft-hearted, mumbled something about no offence being meant, nothing personal, because he was an old man and set in his ways and could see she was half-caste too and nothing wrong with that. Mixed race; Heidi knew you didn’t say ‘half-caste’ any more, thanks to Ruth.

Because after the wedding, the three honeymoonless months which ended when Ruth told her that Marcus was screwing the sister of some garage workmate of his, Marcus walked out. Whether he went to Canada or Australia or, Ruth thought, probably only back to his mother’s house in Bristol, Heidi was left not just with a bump, which turned out to be Harvey, but also with Ruth. Ruth always knew what to do. A year ago, she had told Heidi that she ought to ask the salon for a rise in her wages; Heidi had asked, and she’d got it. Ruth knew about child benefit and housing benefit. She knew where it was best to say Micky lived. Once, in Tesco’s car park, a posh woman had left the boot of her car open with all her shopping in it while she went to return the trolley. Ruth, without saying anything at all, had just calmly removed three of her bags from her boot to Heidi’s, had rearranged what was left, and passed the time of day with the silly cow before getting in and driving off. A chicken, two big tubs of ice cream, loads of other stuff. Ruth always knew what to do. Heidi hadn’t been left with much after Marcus did a bunk, apart from a pregnancy she hadn’t wanted or recognized and which might have precipitated his departure— ‘You want to take a look at yourself,’ had been one of his parting shots, pointing at her fattening belly. In retrospect, spending five thousand pounds on a wedding which hadn’t been made of good solid stuff that would last wasn’t the most sensible thing. But she’d been left with Ruth, who was a good thing to be left with. She was worth it.

That Monday afternoon was Heidi’s day off from the salon, and she’d gone round to her sister-in-law Ruth’s house. Ruth’s mother Karen was there too, visiting from Barnstaple. Sometimes she asked Heidi to do something with her hair, and Heidi reverted from her professional discretion to her schoolgirl hairdressing fantasy, mucking about with Karen’s hair, giving it odd colours and streaks, piling it up asymmetrically for the fun of it, and Ruth joined in too, giving her mother’s hair the odd poke. That Monday, though, it was too hot to do anything much, and they’d started off in the back garden, until Karen had said it was too hot for her—it was the sort of day you liked when you thought about it afterwards—and they’d gone inside. They had put the telly on, and watched one thing after another, Property Deals, Money in the Cupboard, Do or Dare, Cash Cow, for a good four hours. At some point, Ruth brought out a little spliff, and they had quite a nice time, just passing it round. Then, at the end of Cash Cow, Ruth had brought out another one, and they’d smoked that. This had happened before; it was a sort of Monday-afternoon tradition, sometimes going with the mucking-up of Karen’s hair, sometimes just with the telly. Sometimes it was just between Ruth and Heidi, sometimes including Karen as well—she wasn’t some old granny type. Because of Heidi having Mondays off, it seemed like the end of the weekend, which could begin on a Thursday night, too, if it seemed like a good idea. Because of the spliff, and because of the sun shining into Ruth’s front room and onto the screen, they’d drawn the curtains. They’d stayed drawn against the street outside.

Micky wasn’t around that afternoon. He’d gone into Barnstaple to the main library. He wanted to become a member to take out books and DVDs, and he’d made an appointment. They’d told him it wasn’t necessary, but Micky liked to know people were going to be there when he was, and he told them he’d not been interested that much at school, but now he wanted to develop his reading skills. The library had fallen over themselves to make an appointment for him to show him round and talk through, they said, his needs. Later, Heidi said she supposed people weren’t as ready as they used to be to join a library—she knew old folk liked their Shakespeare and that. They’d treat you like royalty if you showed any interest.

Little Archie was asleep upstairs on Ruth’s spare bed. The other kids had come home from school—Hannah and China collected Harvey from his infant’s school, next door to theirs, and Hannah could let herself in and make them something to eat. It was quite normal; it happened like that every day, because Heidi was either working at the salon, or at Ruth’s. Micky was either there or he wasn’t.

Around five thirty they looked up from The Adam Riley Show—he was talking to Jude Vakilzadeh off I Want To Live For Ever. She was showing her new collection of pillowcases, duvet covers and sheets, Heidi later recalled with some exactness. One of the kids was there. At first she’d thought, muzzily, that it was China, but it wasn’t. It was Hannah. She had come in through the back, which was hardly ever locked, and stood in the doorway, holding her own hands, one in each.

‘I won’t be long,’ Heidi said. ‘Put something in the oven. I’ll be back home at six.’ The children were supposed to know they weren’t to bother her on her afternoons off, but any old worry, any crisis no matter how small—a missing cowboy hat of Harvey’s, there weren’t any chocolate biscuits, China had hit Hannah—would bring one of them over the road, usually in tears.

Hannah wasn’t in tears. ‘China hasn’t come back from the shops,’ she said. ‘I don’t know where she’s gone.’ Glum and slow with skunk though Heidi, Ruth and Karen were, they all agreed that was what Hannah had said. Karen thought she’d said, ‘And I’m scared,’ as well. That was probably just her picturesque addition to what Hannah had said, a fat little figure standing in the sun-strewn fog, making clutching gestures. In the corner of Ruth’s front room in the sugary smoke, standing up against the purple-paisley dado strip, Hannah made an unconventional harbinger of catastrophe.

‘She’ll be back home before long,’ Heidi said. ‘I’ll be over soon.’

But Hannah had insisted. China had been away for an hour and a half. Hannah and Harvey had gone out looking for her, and had walked the two hundred yards between home and the shop in the arcade, back and forward, four times. ‘I expect she’s gone to visit a friend of hers,’ Ruth said, irritated. Hannah had insisted. Harvey had wanted a PB and J, and had started bawling. China had gone to the shops—she knew he was sitting bawling, she’d have come straight back.

‘In any case,’ Heidi said to the police later, quite calmly, ‘I knew China hadn’t gone to visit her friends for one straight and simple reason. She doesn’t have any friends. She’s not been a popular girl, ever. They bully her, I expect, because they say she’s fat and she smells. I don’t think she smells, but at that age, it’s always some reason they’ve got to pick on her, isn’t it? I knew she hadn’t gone to visit a friend. To tell the truth, I thought at first, China, she’s playing some trick on her brother and sister. I’ll tan her hide, I thought at first.’

When Micky came back, it was seven thirty. After his appointment at the library, he’d arranged to meet an associate in a pub by the station, and they’d sunk a fair few before Micky had said it was time for him to be getting back. (A junior librarian, the associate and a bored barmaid had confirmed all of this. The barmaid said she’d never have served him the last few if she’d thought for one moment that he’d be getting in a car and driving anywhere.) By the time he got back home, a small crowd of neighbours had gathered at Heidi’s front gate. Micky got out of the car, his blue and yellow hooped T-shirt outlining ample belly and breasts. The neighbours let out a moan of satisfied excitement and interest.

‘What’s going on?’ said Micky. The door to Heidi’s house was hanging open. Ruth came out and looked at him with one of her grimmest faces. By eight, the police had arrived.

4.

There is, of course, no need to worry. There is a process. It is a police process, evolved and tested by a thousand cases that never come to court. That never last more than five hours, most of them. The process searches for a child in a succession of ways, each larger, each more serviced, each more public than the one before. There might be a metaphor here: a series of sieves, each one finer than the previous one. At first the obvious, the nearby is tested, a very few people. But more and more people fall into the sieve, and after a while, everyone is being tested. It escalates, the process, and it escalates quickly. Another metaphor: an escalator, rising like a cliff, speeding—a better metaphor—like a glass lift, rocketing upwards. A case is either solved unobtrusively and swiftly, or it arrives on the front pages of the national newspapers. Almost always it is solved swiftly, and nothing more is heard of it; nobody not related by blood to the child ever hears of it. But there is a process, and it is followed.

The police arrived around eight o’clock. There were two of them at first. They took notes. A male policeman and a policewoman. They sat in Heidi’s apricot lounge, each at the edge of the sofa, smiling wanly. They balanced their notebooks on their knees. ‘Don’t worry,’ one said. ‘Children disappear, and most of them turn up quickly.’ And this was true. They asked about birthday parties China had gone to. They asked about her best friends, and where they lived; about everyone China had ever known on the estate. The children came in, and could add another ten names, tumbling over each other in their urge to be helpful.

‘She’s not with any of them,’ Heidi’s friend—sister-in-law, in fact—Ruth said, walking in and walking out again contemptuously. ‘You’re wasting time.’

The police explained to Heidi—because Ruth had not stayed for an answer—that this was always the first line of enquiry. And then, within half an hour, they left with the names of everyone China knew, as far as Heidi and the children were aware.

The police multiplied. They went to thirty addresses, most of them similar yellow-brick houses on the estate. It was quite late in the evening by now. They knocked on the doors, and a parent came, wondering who it was. A child was summoned from bed or television. But, no, China had not been seen by any of them, not since that afternoon. She’d gone, everyone knew that, she’d disappeared, some of them said; she was there in the street one moment and she was gone the next, the best-informed of them said. By midnight, the last of the names had been canvassed. By midnight in these cases, the process says, most children who have been reported missing in the day will have come home of their own accord. But China had not come home.

Kitty liked to get up early; make a brisk start to the day. When Dennis was still alive, after they had retired, he preferred to stay in bed if he could, sometimes until ten or ten thirty. Kitty’s hours between seven and Dennis’s rising were her own; she could read, or do a touch of quiet gardening in the tubs in the courtyard, or get on with any quiet little task. Or she could simply close the wicket gate behind her and go out for a walk through Hanmouth in the early-morning light, enjoying the wind, or the sun, and the weather, and the shifting moods of the estuary.

Now she was on her own, but she still liked to make a brisk start. Some people did; most people didn’t. There was a small conspiratorial club of early risers, out and about by seven. That was how she had met half the people she knew in Hanmouth, after greeting them as they sailed out in search of their morning paper. Now, turning the corner into the Fore street from the little snicket that led nowhere but to her own back gate, she found herself facing Harry, another of these early risers, with the Guardian in his hand.

‘Hell of a lot of police about this morning,’ Harry said, when they had exchanged the usual greetings. ‘You don’t know what it’s about?’

‘I hadn’t seen,’ Kitty said. ‘I’ve only just come out.’

‘A hell of a lot,’ Harry said. ‘Down the Wolf Walk, poking round the car park at the doctor’s surgery, and there’s even a chap putting on scuba gear with his legs dangling over the quay. Dozens of them.’

‘Gosh,’ Kitty said. ‘How exciting. The Queen’s not coming, is she?’

‘Not that I’ve heard,’ Harry said. ‘I can’t think what it could be.’ He waved briefly with his umbrella, and let Kitty go on her way.

The next stage of the police process had begun overnight. It had not been announced. At first light, mud-brown and frail, twenty police were scattered over the wild places of the parish; wherever was overgrown and abandoned, wherever was wild, the police were. At the edges of Hanmouth, the clouded dawn showed police eyeing empty lands: the bird sanctuaries, the abandoned huts and sheds and workshops, which can be found everywhere in England. In the warm night, the police had arrived in vans, and in the fields about the city, in the woodlands, in long waders in the muddy estuary, the police walked with a strange, crane-like gait, their faces downwards, no more than a body’s length between them. They went slowly and gracefully through the waste ground, the unfarmed lands, the woods and clearings, and even along the undredged river. As Harry had seen, there was a scuba diver sitting at the edge of the quay, and soon, when the shifts ordained by the police authority changed, there were four more, at the quay, at the jetty, along the Wolf Walk. They plunged into the high water, again and again, surfacing, plunging, surfacing in further and further places. On the quay, a senior policeman stood; he did not take his own notes, but had a subordinate to do that. From time to time, he was informed of progress. Last night he had not been told about the girl’s disappearance. This morning he had been told, and he was inspecting the wild places, the hiding places, the places where a child could disappear and find no way out. The mood was calm and systematic. They were working through their process. By eleven, the tide was low, and the wet, brackish mud hissed as the water drained from it, like geese or rain. The scuba divers stood in it, thigh-deep. There was nowhere to go but further towards the ocean, where the estuary still ran deep and secret.

‘Apparently,’ Doreen Harrington said in the coffee shop at eleven, ‘they’re looking for a small girl. Gone missing.’ She popped a gobbet of cheese scone into her mouth, swilled it with coffee, and went on talking, her manners not being all they should be.

‘I saw some police divers at work in the estuary as I was coming out,’ her friend Barbara said. ‘Has she fallen in, do they think?’

‘They don’t know,’ Doreen said. ‘I was speaking to a nice young constable—I saw him going into the old workshop at the back of me, the abandoned one, and I didn’t see his uniform at first. I thought it might be kiddies going in to make mischief, so I went over to chase him out, but he explained everything. It’s a little girl from the estate; she disappeared yesterday afternoon and hasn’t been seen since. They don’t know what’s happened to her. The divers, it’s just a precautionary measure.’

Mary and Kevin, who ran the coffee shop, had heard Doreen’s informed knowledge. They now came over, he from the kitchen in a striped and flour-dusted blue butcher’s apron, she in a waitress’s frilly one, a pencil in hand. ‘I do hope she hasn’t been—that there’s no talk of anyone taking her—that—’ Mary said.

‘Paedophiles, you mean?’ Doreen said, in a frank, open tone. ‘They simply don’t know.’

‘But they wouldn’t be fishing in the estuary, would they,’ Barbara said, ‘if they thought it was paedophiles?’

‘They have to exclude every possibility, systematically,’ Doreen said, whose nephew was a constable in the Hampshire constabulary. ‘They’re doing all the right things, I’m sure.’