Полная версия

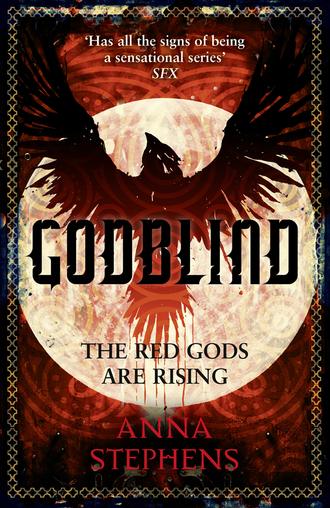

Godblind

‘I don’t want your goat,’ she hissed and the cat’s yowl went up an octave. She edged back the way she’d come, back in the direction of her pursuers, wondering which way to die would be least painful. Probably the cat. But the cat’s ears were better than hers and they pricked up, the rumble of threat dying in its throat. It’d heard those hunting her despite the howl of the wind. They were closer than she’d thought, then. She cursed and looked behind, catching flickers of torchlight further up the mountain, the faintest tang of smoke. Liris’s blood was a beacon calling to the dogs, and she hadn’t had the foresight to wash it off. Now it was too late.

Stay ahead of them, get down into the foothills, find someone who’ll help. She shifted back towards the cat and its ears flattened, then pricked again. Face it, no one’s going to help a woman dressed in blue and covered in blood. You’re dead whoever finds you first. Rillirin swallowed tears and shoved her hair back out of her eyes. Then fuck you all, she thought, I’ll save myself. Somehow.

Gripping the remains of the goat, the cat bounded lightly down the sheer rock face on to a ledge Rillirin hadn’t noticed and vanished, its pelt as patchy white as its surroundings. Follow it or follow the path? Could the dogs handle the cat’s path? Could she?

A faint howl on the wind made up her mind for her and she edged on to the steep rock, her boots scrabbling for purchase, the wind tearing at the remains of her skirt and throwing her off balance. She skidded, fell hard on her right hip and was sliding down the rock before she’d had a chance to suck in breath to scream.

She hit the cat’s ledge, winded, and sailed on past, faster, stone burning the backs of her legs and arse until there was no more mountain and then she did scream, falling through space for long, endless seconds, eyes screwed shut, arms flailing uselessly through the air.

She hit water so cold it felt like knives stabbing into her. She’d thought herself cold before, but this was cold that burnt. Everything constricted and she hit the bottom. Fighting her way back up against the drag of her skirts, her head broke the surface and she warbled in a breath, lungs burning as well as her skin. She opened her eyes in time to see the rock the current slammed her into, crumpling her body and forcing her head back beneath the icy surface. She rebounded and the current swept her on, every breath a choking effort against the cold and the insidious lethargy creeping through her limbs.

She could hear the echo of men and dogs lost somewhere behind her, far above the river. If she survived the cold, survived the weight of her skirts dragging her down, survived the rocks, rapids and falls, she’d gladly pray daily for the rest of her life to any god who’d have her.

The river’s voice changed, deeper and angrier, a full-throated roar. The cold, the pain: none of it mattered. There was a waterfall ahead, and Rillirin wasn’t sure she’d survive this fall. She started to paddle, then to thrash, her limbs heavy and dull. The current picked up, swirling her with playful malevolence into the centre of the river, and then again, endlessly, she fell.

Rillirin must’ve gone another half-mile after the waterfall before the water slowed and she managed to haul herself on to the bank. She’d seen enough slaves die of cold in Eagle Height and so she stripped off her gown. She wrung out the worst of the water and then used the rough material to scrub hard at her skin, stimulating blood flow. At least I don’t smell of blood any more. A giggle escaped through chattering teeth.

She staggered forward, fell to her hands and knees and stared blearily at the ground. Pine needles. She crawled forwards into the shadow of trees, a copse so small as to not be worth the name. The wind still howled through the trunks and gouged her skin but the softness under her knees brought tears to her eyes. She squirmed behind a trunk and the wind lessened. Rillirin curled on her side and dragged at the ground, piling needles up and over her, heaping them on to her thighs and flank and chest, against her shoulders and around the back of her head, draping the gown over the top. It cut the wind even further. A few minutes to restore some warmth and she’d look for some way to make a fire. Just a few minutes …

Rillirin blinked and stretched, felt an immediate bite of cold as the pine needles slithered away and the damp wool of her gown settled against her skin.

Daylight. Fuck, she’d slept all night. They could be right there, right behind her. Rillirin lay still, her eyes roaming between the trees and out on to the mountainside. The river chattered angrily behind her, swollen with snowmelt. There wasn’t any movement, and she didn’t expect the Mireces would wait for her to wake up before taking her captive. Had they passed her by, or missed her completely and taken the path she’d meant to take herself?

Rillirin slid to her feet and into her gown, torn and ragged now, one sleeve missing, but all she had against the cold. Checking for movement, she crept to the bank and splashed water into her mouth, wincing at the cold and the pain in her face and jaw, pain which started to spread throughout her body as her muscles woke.

A sharp wind carried the sounds of dogs and men, as though they were made of it, appearing every time it blew, allowing her no respite. With no time for thought or to plan a direction, Rillirin began to run again.

GALTAS

Eleventh moon, seventeenth year of the reign of King Rastoth

The palace, Rilporin, Wheat Lands

‘Your highnesses, it is an honour.’ The physician’s bald head winked in the light from the window as he bowed. He gave a short nod to Galtas. Galtas managed a smile and looked back out through the window, bored already.

‘Master Hallos, the honour is ours,’ Prince Janis said. ‘Thank you for coming; we know how busy you are.’

The honour is ours? Sanctimonious little prick. Galtas unsheathed his dagger and used the tip to clean beneath his nails. Busy? Busy failing to cure the king. Rastoth the Kind, they used to call him. Rastoth the Mad now. A smirk pulled at his lips and he bent his head so no one would see.

Hallos took a seat in the heir’s small study and eyed the princes. He smoothed his beard, uncomfortable. ‘King Rastoth’s mind remains as sharp as ever, his intellect as great. These … confusions have nothing to do with age or infirmity, that much I am sure of now. I would venture they are the result of grief, Your Highnesses, a grief that has not lessened since your mother the queen’s demise.’

Janis glanced at his brother, and Rivil’s smile was wan. Galtas rolled his eyes. ‘A grief we share with our father but, perhaps, are bearing a little better.’

Hallos sighed. ‘Your mother’s loss has destroyed the king’s peace. He cannot conceive of a world without her by his side. It troubles him, disturbs his sleep, his equilibrium.’

‘If we could only find those who took her from us,’ Rivil said, voice coiled with anger. Janis put his hand over Rivil’s clenched fist. ‘I speak with Commander Koridam every week, read the reports he receives, and nothing. Still nothing. Almost a year has passed and still her killers roam free.’

‘This failing is not yours, Rivil, nor mine, nor Koridam’s. The culprits will be found eventually, found and brought to justice. We must trust in that.’

Galtas leant his shoulder against the wall by the window, his back to the group before the fire. Pious, pragmatic, devoted Janis. It was exhausting just listening to him. The man was as dull and pointless as an ugly woman. A clever, ugly woman. Galtas suppressed a shudder.

‘Queen Marisa is with the Gods of Light now, Prince Rivil,’ Hallos murmured. ‘Be at peace knowing that. There is no more suffering for her.’

‘Fuck the gods. I have prayed to the Dancer and the Fox God both, asking them to bring her killers to justice, and yet my father still suffers. They still remain free,’ Rivil said, sullen with anger. ‘My brother suffers. I—’ His voice broke and he looked away, biting off the words.

Galtas glanced back, watched Hallos and Janis pause, awkward in the face of Rivil’s grief.

‘I have found a sleeping draught aids the king. Restful sleep does much to restore his strength. If you would like …?’ asked Hallos delicately.

Rivil looked up and wiped at his eye with his thumb. He scrubbed his fingers through his dark gold hair. ‘Thank you, but please, save all your efforts for my father. I fear our enemies may seek to take advantage of his illness soon.’

Janis frowned. ‘Rivil, this is not the time.’

Rivil’s eyes darkened, but Janis didn’t notice. Janis never did. Galtas saw it, though, oh yes. Galtas always noticed.

Rivil focused on Hallos. ‘And the visitations?’

‘At present I have been unable to stem their flow. If anything, they are increasing in number and severity. It may be your father’s way of coping, or working through his grief. In time I believe they will cease.’

‘So you don’t really think he sees my mother’s spirit?’ Rivil asked and Janis coughed, closing his eyes. Rivil ignored him again.

‘I think he wishes to see her, wants it so hard that his brain tells him she’s there,’ Hallos said. He spread his hands. ‘And yet her soul rests in the Dancer’s Light now. Souls do not return from that.’

Janis pushed up out of his chair and Hallos and Rivil rose to their feet. Galtas pushed away from the wall and put away his knife. ‘I think that’s enough for now. Thank you, Master Hallos. We won’t keep you any longer. Rivil, a moment, if you will. Galtas, you stay too.’

Galtas exhaled a deep breath, knowing what was coming. He stayed by the window, unwilling to attract Janis’s attention more than necessary.

‘What was that nonsense about spirits? I need you to grow up, Rivil. You cannot avoid your responsibilities – or the real world – forever. You may be the younger son, but you are also a prince of the blood with duties to Rilpor and the throne. So I’m asking you to act accordingly.’ Janis stared at Rivil, lips pursed. ‘Don’t make me make it an order,’ he added, and Galtas’s eyebrows rose.

A muscle flexed in Rivil’s jaw as he nodded, nostrils flared. ‘You are right, of course, Janis. I forget myself.’ He sounded sincere, at least.

I, on the other hand, forget nothing, Galtas said to himself, glaring at Janis’s back.

‘I know Mother’s death hit you harder than you care to admit, brother. But it’s taken something from all of us, don’t forget. And yet we must keep going, stay strong. While the northern and southern borders are secure, General Koridam’s latest report from the west indicates increased movement from the Mireces. They’ve made a couple of late raids, later than we would expect. The folk of the Cattle Lands and the Western Plain are afraid. They need strong direction from the throne, messages of support. You can aid in that.’

He clapped Rivil on the back while Galtas stifled a yawn. Still in love with the sound of your own pompous voice echoing out of your arsehole. I’ve done farts that had more substance.

‘We cannot afford to fail, Rivil. We must make a responsible adult out of you,’ Janis said and grinned to lighten the mood.

‘Gods, I hope not.’ Rivil laughed. ‘I quite like being the rebellious prince.’

‘A part you often play a little too well,’ Janis said.

Rivil inclined his head. ‘The burden of kingship will fall to you, not me. I can afford to have a little fun—’

Janis’s face was hard. ‘No, Rivil, you can’t,’ he interrupted, souring the mood once more. ‘Not now, with Father so ill. Maybe not ever again, not in the way you mean. Understand that. Accept it. Royalty is a privilege and a burden, not a game.’

‘You act as though you are already king,’ Rivil said hotly. ‘Our father still lives.’

‘At least one of us is taking responsibility for his duties,’ Janis said. He bit off whatever he was going to say next and strove for calm. ‘Whatever the reports say, I do not believe our borders are as safe as we would like. We must be ready. We must—’

‘I’m well aware of the monsters at our door, Your Highness,’ Rivil said with icy formality. ‘There’s no need to keep reminding me all the time. I do my duty, and will continue to do it.’

‘I know you will,’ Janis said, and Galtas was surprised he couldn’t hear the anger in Rivil’s voice. Or maybe he just dismissed it. ‘Which is why I need to you sit in the plains court this week. Galtas, keep an eye on him. The court, not the tavern, you hear?’ Galtas inclined his head. ‘Good. Then I’ll see you for supper.’

They stood for a few seconds longer, but Janis was already at his desk and shuffling through reports. And so easily are we dismissed, like boys to our rooms for a misdemeanour.

Galtas followed Rivil into the corridor and closed the door with a gentle click. ‘He does not—’ he began with a hiss.

Rivil waved him to silence, but his face was white with anger. ‘He is the heir. So he does. I must accept it.’

Galtas looked both ways along the corridor. ‘You would make a better heir than him.’

Rivil held up his hand again. ‘Don’t.’ He stretched the tension out of his shoulders. ‘I’m to the plains court, then. I’ll see you tonight.’

Galtas watched him walk away, and then stared hard at the door to Janis’s study, fingers tapping on the pommel of his sword. Eventually, he left.

DOM

Eleventh moon, seventeenth year of the reign of King Rastoth

Scout camp, Final Falls, Wolf Lands, Rilporian border

They’d climbed out of the forests cloaking the foothills and into snow and ice, isolated copses of stunted firs and pines providing scant but welcome cover. There was nothing to stop the wind up here and its constant keening set Dom’s nerves on edge, kept the pain in his head thrumming. It would help if he knew what he was looking for, but that hadn’t been made any clearer over the last day.

The scout camp was perched just above the Final Falls on the River Gil, a shelter cleverly disguised with snow and rock so it was invisible from above. If the Mireces ventured down the treacherous Gil-beside Road, the scouts would spot them and run ahead to the village with the warning. It was a miserable posting, but there hadn’t been a surprise attack in the years since they’d implemented it.

They were met with enthusiasm and Dom was grateful for the distraction. Lim and Sarilla were soon absorbed into the group and it took little effort to slip out when everyone was occupied. Ash had the forward post, sitting a hundred strides further upriver, and Dom slapped his fur-covered shoulder as he passed.

‘Where are you going?’ Ash asked.

‘Crossing over and a bit of a wander,’ Dom said.

Ash stood up. ‘On your own?’

‘On my own,’ Dom confirmed. ‘Had a knowing. Said to come looking.’

Ash chewed his lip. ‘That’s not the best idea, and I’ve heard you come up with pretty bad ones over the years.’ He hefted his bow. ‘Let me come?’

Dom looked up at the white and black of the mountain. ‘I’ll only be a few hours,’ he said. ‘If I’m not back by then, come looking, all right? And keep an eye on the path,’ he added as something tugged inside him.

‘Stay safe,’ Ash said and Dom could see his reluctance. Dom nodded and hopped from rock to rock across the river. His wolfskin jerkin cut much of the wind but it was still bitterly cold, and he hunched his shoulders and walked until he was out of sight and sound of the river.

‘All right, then,’ he muttered, closing his eyes. ‘Where am I supposed to go? Whatever this key is, I could do with some help to find it.’

Nothing.

Dom huffed a plume of breath into the air and picked a direction at random, northeast uphill. The Dancer’s messages were often obscure, but this was ridiculous. Go and wander about in enemy territory looking for something, but I can’t tell you what it is. You’ll be fine.

He had a sword, a short bow and quiver, and a knife. Oh, and a tendency to fall down and commune with the gods at the most inopportune moments, don’t forget. He snorted, wiped his nose, and kept walking. No doubt Lim would be apoplectic when he returned, so he’d better make sure he found whatever it was he was looking for. Returning empty-handed would be even worse.

‘If this goes wrong, I’ll never live it down,’ he breathed. His inner voice pointed out he might not live at all and he grimaced, but kept trudging. It was stupid, he knew, yet it felt right. The key was out here somewhere, the message that could confirm or deny the start of something that would change the world.

A squall blew in and ice crystals filled the air, making everything hazy and soft, so it took a few seconds to make sense of what he was seeing. A copse of pine, a movement of red like fox fur near the ground. But any foxes this high up would have turned white by now. Dom squinted and took a few more steps, and the thing moved, stood up, started to run. Red hair. Blue dress.

Mireces.

The wind dropped and the noises that had been concealed by it echoed across the mountain. She saw him and veered away, then jinked back again when men appeared from behind an outcrop. Mireces hunting Mireces.

‘This is not helpful,’ Dom muttered as he dropped into the snow and snatched an arrow, aimed low and took the first hunter in the belly. The second shaft hit the next hunter in the shoulder and he kept coming; the third was a mistake. The third took the man with the dogs in the throat and he let go of the leads as he died. Two dogs, big, with lots of teeth. One sprinted for the girl, the other came straight for him.

Two dead and one injured, but there were four more now and they had bows too, and Dom had no choice but to hunker down as arrows rained around him. The girl was screaming and the sound triggered a rush of light in his head. It was her. He was here for her. ‘Balls,’ he said as the dog barrelled into him and sent him over on to his back.

Dom jammed his right forearm into its mouth, the heavy leather armguard just about protecting his flesh. The dog shook him and Dom’s punches missed. He thrashed, dragged his knife free and stabbed the dog’s belly. It squealed, but didn’t let go. He stabbed it again, trying not to look in its eyes. Sorry. Not your fault. Sorry.

The dog collapsed and Dom struggled from beneath it, scrabbling for his bow. The other dog had the girl by the calf and she was screaming louder as it shook her like a rabbit. The Mireces were closing in on them both when three were dropped in less than a second with arrows Dom hadn’t fired. The man with the arrow in his shoulder turned and fled, and Ash popped up from behind a rock and killed the dog savaging the girl.

‘Thanks,’ Dom said. ‘Good to see you ignored me.’

‘Don’t I always?’ Ash asked, quartering the mountains with an arrow on the string.

‘Let’s get her.’

‘Her?’ Ash asked, frowning. The girl was dragging herself away, her blood a bright trail in the snow. ‘Let the Wolves do for her. Mireces scum.’

‘No,’ Dom said, ‘she’s why I’m here. She’s the key. The message.’ The harbinger. He shook away the thought.

‘Oh, gods,’ Ash muttered. ‘Are you sure? I mean, really sure? Because we’re going to be leaving sign all the way back. We’re bringing them right to us.’ Dom spread his hands but didn’t answer. Ash sighed. ‘Fuck. Fine, then let’s be quick about it. Who knows how many more are out there? Come on.’

They cornered the girl and she curled up small, hiding her face in her hands. ‘Here to help,’ Dom said soothingly. ‘But we need to leave now, get you to safety.’ She didn’t move, didn’t respond. ‘All right, up you come,’ he said and put his hand under her arm. She squealed and kicked and Dom felt a throb up his arm into his head. Definitely the key. ‘Stop,’ he said, making his voice hard. ‘We’re trying to save you.’

He dragged her to her feet and she shrieked as her torn leg took her weight. Dom and Ash slung her between them and made their way down the mountain and back towards the river and dubious safety.

They didn’t go to the scout camp. Ash left Dom to drag her further downhill and went to fetch Lim and Sarilla.

Dom went a half-mile straight down, into thicker forest and patchy snow, and eased her down beneath a fir tree. He took off his wolfskin and wrapped her in it, hooked his bow and quiver on a low-hanging branch and loosened the long dagger in its sheath. She watched him with big grey eyes in a pinched face.

‘You have got to be joking.’ Lim didn’t even look at him, just crouched opposite the girl and stared at her. The bites to her calf were bad, the blood the brightest, cleanest thing about her. The exposed flesh of her arms and legs was filthy, scratched and too pale with cold.

‘You’re safe, you’re safe,’ Dom said as Sarilla and Ash loomed above her. ‘We’re here to help, all right? Your pursuers are dead’ – he glanced at Ash – ‘mostly. There’s nothing to fear.’

‘What’s your name, girl?’ Lim asked. Dom pulled a roll of linen from the pouch on his belt, rubbed gently at the bite marks with snow, and then bandaged her leg. He shivered, saw her note it and glance at the wolfskin she was wearing. Come on, two nice things I’ve just done for you, not including saving your life. So give us something in return.

She was silent.

‘She’s your key? A Mireces?’ Lim asked. Sarilla and Ash were eyeing the landscape as they listened and Dom knew the scout camp would be on high alert.

Dom licked his lips and squinted. ‘She’s the key,’ he murmured, the words again coming from somewhere just a little outside of him, a touch beyond his control. ‘But not Mireces.’ She glanced at him at that, and then away. ‘I’d say an escaped slave—’

‘She’s a spy,’ Ash interrupted. ‘What better way to infiltrate us? A young woman, cold and filthy and starving … they know we’d take her in. So we don’t.’

‘Send her on her way?’ Lim asked.

‘Knife in the throat’d do it,’ Sarilla muttered.

Dom winced, but he couldn’t blame either of them. Except that they were wrong.

‘What’s your name?’ Lim asked again. Still nothing. ‘We’re trying to help here, lass, but you’ve got to help us too.’

‘My name’s Dom Templeson,’ Dom tried with his most ingratiating smile. ‘This is Lim. He’s our chief. The scary woman is Sarilla and that’s Ash. He’s a hothead despite the cold.’

‘Fuck off,’ Ash said. ‘I wish they’d finished her off. You do realise you’ve compromised the camp, and possibly the village, by taking her and killing the Mireces? And for what? Some fucking mute who’ll likely murder us all in our sleep.’

‘You don’t wish that, because then she’d be dead and we wouldn’t know anything,’ Dom snapped as Lim snorted. Best get it over then, he thought. He reached for her face and she squirmed backwards, got her good leg under her and stood, cracking her head on a branch and sending a flurry of snow down on them all. Dom paused, secretly glad of the delay. The tremor he’d felt while carrying her had been strong, verging on painful. He wasn’t all that keen on repeating it, but if she wouldn’t talk, there was little choice. He needed to learn what she knew and he could probably force a knowing if he held on to her long enough.

‘The Mireces are hunting you,’ he said and saw her shudder, ‘so we will protect you. But you need to help us do that.’

Lim looked at him, surprised, and Sarilla and Ash turned from their study of the terrain with identical expressions of disbelief. ‘We’re helping her,’ Dom said firmly. He ignored the mutters and focused on her again. ‘Are you Rilporian?’

The girl nodded and Dom felt a flicker of triumph. ‘Were you captured by the Mireces?’ Another nod. ‘I need you to say something now, lass,’ Dom murmured, taking a soft step forward. She wasn’t fooled; she slid sideways out of his reach. He stopped moving and exhaled softly. ‘I need you to tell me where you escaped from. Can you do that?’