Mindsight

Полная версия

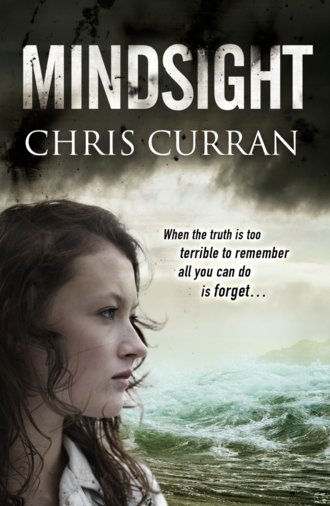

Mindsight

Жанр: приключениякниги по психологиидетективызарубежные приключениясовременная зарубежная литературазарубежные детективызарубежная психологиякниги о приключениях

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2018

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу