Полная версия

One Hundred and Four Horses

One Hundred and Four Horses

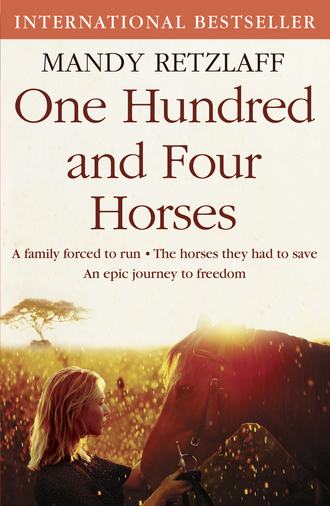

A family forced to run

The horses they had to save

An epic journey to freedom

MANDY RETZLAFF

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 77–85 Fulham Palace Road London W6 8JB www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain

by William Collins in 2013

Text © 104 Horses Ltd, 2013

The author asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Cover photographs (posed by a model) © Lara Wernet/NA/Novarc/Corbis (woman and horse); Panoramic Images/Getty Images (tree).

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Find out more about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780007477555

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2013 ISBN: 9780007477579

Version: 2014-08-22

This book is dedicated to all our beautiful horses, and especially to those no longer with us— may their spirits run free.

Set a beggar on horseback, and he’ll outride the devil.

—GERMAN PROVERB

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Ten Years Earlier

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Mozambique

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Epilogue

Picture Sections

About the Publisher

Prologue

THEY SET OUT as night was falling, but it is almost dawn and there has been no sign of my husband or our horses.

I stand on the wide veranda of the old colonial farmhouse, trying to make out shapes in the early morning gloom. Before Pat left, he told me to get some sleep, but he has done this before—midnight missions to rustle our own horses off land we no longer own—and I know how it goes. Tonight, there is no way I can close my eyes. Whenever I do, all I see are images of the terrible things that might be happening, even now: my husband, so near to me, yet surrounded by men who might block the roads and build up barricades to stop him from getting out. Consumed by thoughts like that, I can do nothing but wait.

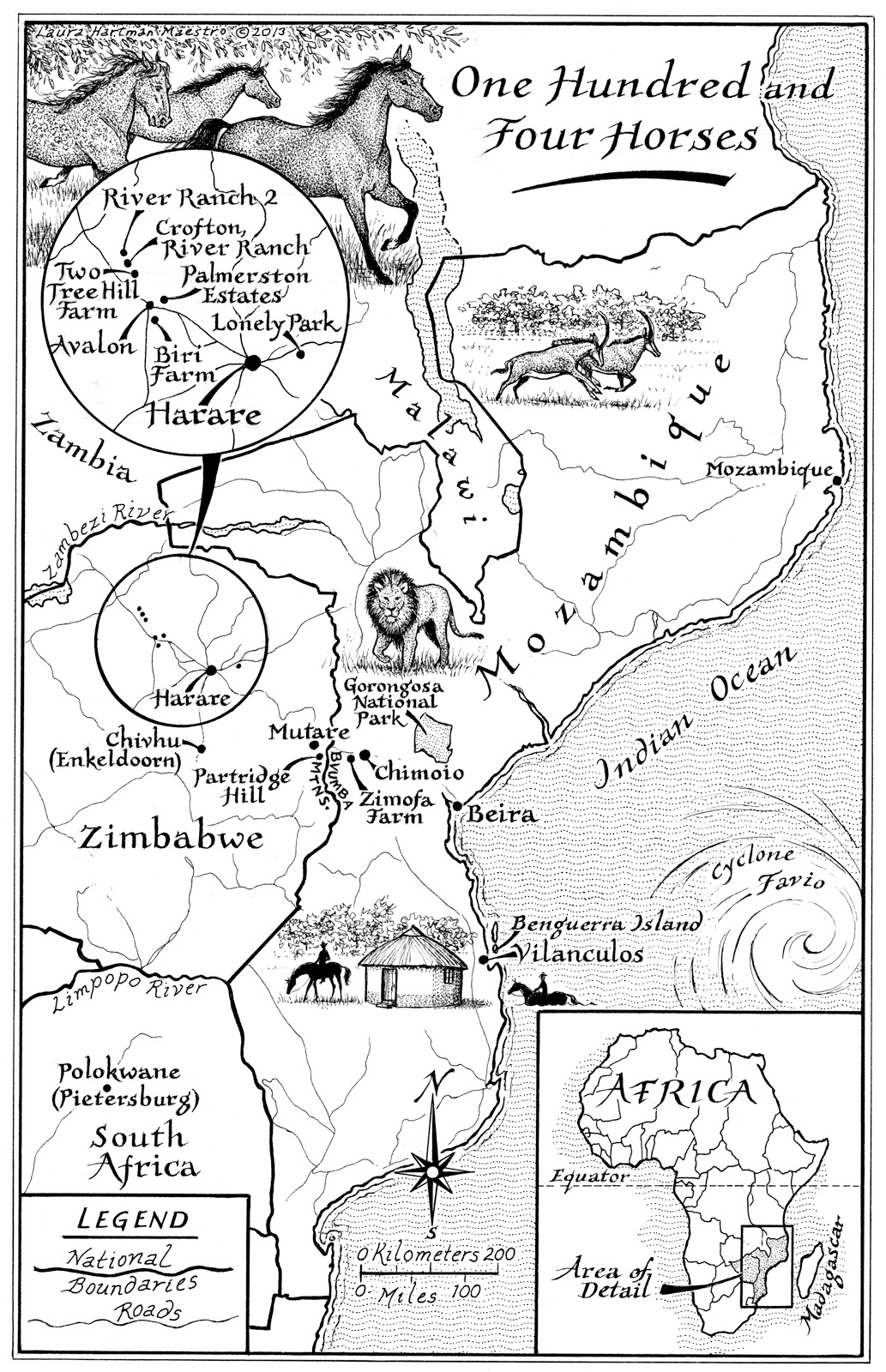

It is September 2002, and it has been only twelve hours since the Land Rover arrived at the gates of Biri Farm, our home in Zimbabwe, southern Africa, for the past nine months. Biri Farm stands ten kilometers across the veld from where I now stand, but it might as well be in another world.

Once the Land Rover was gone, Albert handed me a letter. We had, the letter said, only four hours to leave Biri Farm. If we dared to remain, we would lose everything: our horses, our worldly possessions, even our lives. By government decree, Biri Farm was no longer a safe haven.

Now I stand in the eerie chill before dawn, wondering what has taken my husband so long. The farmhouse behind me belongs to Nick Swanepoel, a good friend and neighbor. So far, his farm, Avalon, has been safe from the chaos spreading like cancer across our beautiful country of Zimbabwe. He has agreed to shelter us for the night, to take in our herd of horses until we can spirit them to a new home, and the farmhouse is piled high with all the boxes we managed to rescue from Biri. Somewhere in there, my mother is sleeping too, barely able to comprehend the madness that has become our lives.

There are ten kilometers between here and Biri Farm, but the mist is low and I can hardly see the end of the field in front of where I stand. Pat should have been back by now. I shift nervously. All he had to do was get back onto Biri, rope up the horses, and lead them to the safety of Avalon. There was never any question, I knew, of leaving our horses behind. They are the horses of our friends, the horses of our neighbors, horses we have promised to protect. Some of them have been with us since the very beginning. Others joined us along the way. Many have already been driven from their own homes, attacked with spears or pangas—knives—or abandoned on farms as their owners fled. They are our responsibility, and we are all that stands between them and long, drawn-out deaths from cruelty and neglect.

I hear movement behind me. Knowing that it is my mother, come out to make a fuss over her daughter—even though she is well into her seventies, she will always make a fuss—I turn around, preparing to tell her that everything is fine.

“Any sign?”

I shake my head.

“They won’t be long,” she promises, though she can hardly know. “It’s a long trek with seventy horses.”

I close my eyes. When I open them again, at last I sense movement. It seems only that there is something out there, yet everything around me is black. All the same, something tingles up and down my neck. I am certain now: there are different textures in the darkness.

“Mum?”

“What is it?”

“It’s them …” I whisper.

Slowly, the shapes appear out of the darkness. At first they are like ghosts. It is only when I move forward, willing the ghosts to come to life, that those shapes begin to have definition. First, a man, a groom, trailing a long rope behind him. Then, a horse, bobbing contentedly forward, wearing a halter but no saddle. Then, more horses alongside, each with a lead rope dangling from its halter. One, two, three, four, five … The procession continues into reaches of darkness I still cannot see.

“Is Pat with them?” asks my mother.

I cannot see my husband yet, but still I nod.

They weave along a track between fields of irrigated wheat, disappearing behind reefs of low gray mist and then coming back into sight. I know how many horses there will be, because I know them all by name. We have seventy-one now, but before long there will be more. Some days, the phone does not stop ringing. All across this once-proud nation, farms are being abandoned; farmers are fleeing, but in their wake are the animals they cannot take with them.

Then, at last, I see Pat. He is moving on the far side of the herd.

He is holding a lead rope in his hand—though, in truth, he does not even need that. The young mare he is leading, though a new addition to the herd, will do whatever he asks. The tallest and proudest of all our horses, she stands seventeen hands high, an aristocratic dun mare with beautiful black points and eyes that positively shimmer with keen intelligence. Shere Khan is the self-appointed queen of the herd and, like the queen that she is, helps Pat guide horses and grooms to safety.

There is an old German proverb, one I sometimes imagine Pat’s great-grandfather might have used. Set a beggar on horseback, they used to say, and he’ll outride the devil.

We have to outride the devil, that much is true—but watching the herd walk onto Avalon Farm, I wonder how long we can stay in the saddle.

“I see you’re back,” I say when Pat comes closer, not wanting to tell him how worried I’ve been.

“All of us.”

Damn him, but he is almost grinning.

“Well?” I ask. “What now?”

Pat makes as if he is thinking about it. Behind him, the half-Arabian Grey and our daughter’s mare, Deja-vous, are grazing the long grass, but even they must have some idea of what is going on all around us.

“We’ll do what we always do,” Pat says. “We’ll make a plan.”

TEN YEARS EARLIER

Chapter 1

I REMEMBER A place that was wild and filled with game. I remember a house with a giant mango tree in the garden and stables out back, where our horses grazed contentedly and waited to be ridden along dusty red tracks that wound their way into the bush. I remember picking up our children from school and driving home with the tsessebe—those powerful antelopes with chestnut hides, spiral horns, and strange, ridged bodies—flocking into the trees alongside us. The farm was called River Ranch, the farmhouse Crofton. The farm’s thick-forested hills and scrubby lowlands were held in the cradle of two rivers; its boundaries were patrolled by elephants tamed and trained to keep away poachers. Its soils held the promise of a new future, and on the day that my husband, Pat, and I took our children there for the very first time, in 1992, we thought it would be home forever.

That day, long ago and yet seemingly so near, we drove north on the Chinhoyi road, through fields of tall maize. Our car was laden with suitcases and packs, saddles and straps, and three squabbling children in the back. In the middle seat, our second son, Jay, was chattering animatedly about the game he might see. If there was one way of sparking the often taciturn Jay to life, it was to talk about the game he might track and hunt at our new home. The kudu, that large African antelope with its striped hide, huge horns, and powerful legs Pat and I had seen when we were first looking over the farm, had been one of the things that propelled us to go to the auction and place a bid; this wild place was where we would spend our lives.

We followed the winding, dusty road and could soon see the farmhouse of Two Tree Hill, the farm that bordered our own, looming above us, with big workshops and a water tank in front. Farther on, we saw the glistening waters of the dam. A herd of the enormous black antelopes known as sable looked curiously at us then turned and sped away, through the wheat and into the cover of the thick bush. Behind us, the truck that was following jarred on patches of uneven road, but the four horses inside were content. This, after all, was to be a new home for them as well.

We reached the farmhouse early in the afternoon, when the midday sun was at its hottest. The building had a broad white facade and a simple roof of corrugated iron. Pat pulled the car around, into the shade of the mango tree, and, even before we had ground to a halt, the children tumbled out.

Paul, our eldest, was fourteen years old, big and broad and the perfect image of his father. Jay, just turned nine, had a mop of wild blond hair that almost hid his searching green eyes. Our youngest, Kate, was three years Jay’s junior, a gorgeous girl who, surrounded by brothers and cousins, was growing up as tough as any of them and gave as good as she got.

“Is this it?” Kate asked.

“Your new home,” I replied. “The farmhouse is called Crofton. What do you think?”

As Paul, Jay, and Kate inched forward to investigate, Pat and I turned our attention to the truck that had followed us onto the farm. Pat undid the latches and let down the ramp. Inside the truck, he ran his hands up and down the four horses’ noses, promising them fresh air, clean water, and more grazing than they could wish for.

Frisky came first, her ears twitching inquisitively. An old skewbald mare, more than twenty years old, she barely needed leading. She simply followed the sound of Pat’s voice. It was the same voice she had been hearing for twenty-two years, since the days when they would race antelopes together at Enkeldoorn (now called Chivhu), where Pat grew up. She was his very first horse, perhaps his very first friend, and I sometimes wondered which one of us was the real love of Pat’s life.

After Frisky came her foal Mini, a bay mare with a wild temperament who had produced some very special foals. Once they were out, they turned to survey their new surroundings, while the other two horses, Sunny and Toffee, lingered in the shade of the horse trailer, unsure if they too should emerge.

While the children were looking up at the face of their new house, Pat ran his hands along Frisky’s flank and listened to her responsive snort. His old friend took a few steps forward and dropped her head to start pulling the strange new grass between her teeth. When next she looked up, her nostrils twitched and she rolled her eyes.

This will do, she seemed to be saying. If you say so, Patrick, this will do.

When I look back now, moving to Crofton was a new beginning. Crofton was a place in which we wanted to invest the whole of our lives. We were to be surrounded by rugged, virgin bush, and we had set our sights on opening up and forging a productive farm, one that we might one day hand down to our children. It would be a place for the generations to come, and Pat and I would found it while our children had the most amazing childhood they could, running wild in our beautiful Zimbabwe.

I did not know that nine years later, our world here at Crofton would end.

I had met Pat in 1976, when he was studying at the University of Natal in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. I had not met many Rhodesians before, having been born in Ghana and brought up in South Africa, but as soon as I met him I knew that he was the man for me. I had taken temporary work as a barmaid at a hotel popular with the university’s students. Although I had never been to university myself, student life had become my life. My nights were filled with raucous laughter and parties, and I had become part of a big circle of friends, all of whom were studying at the university. Every year, the university held a fund-raiser they called Rag Day. On Rag Day, the students would build huge floats. Vast figures would be cast in plaster of paris, and garlands of flowers would cover trailers and cars. The students would climb on top of the floats and the procession would move along the streets of Pietermaritzburg, while we would all collect loose change for charities.

On Rag Day of 1976, I clambered onto one of the floats and headed off with the other students. As the floats lumbered along, we leaped on and off, proffering our tins, and the crowds in the street cheered wildly as each float passed by.

From somewhere in the crowd, I heard somebody calling my name. Standing, pressed between two other students, was a good friend from the university called Charlie Bender. He had caught sight of me on the float and was trying to attract my attention. When I spotted Charlie I waved back enthusiastically.

I did not notice Charlie’s tall friend who was standing beside him. His name, I would later find out, was Patrick Hugo Retzlaff. It was much later in our relationship that I found out that Patrick had nudged Charlie and asked him who the waving girl was. When Charlie told him my name, Pat said, “Well, that is the girl I am going to marry. I have had a strange premonition.”

Some months later, I was introduced to Pat for the first time. In the crowded hallway of a mutual friend’s house party, we talked long into the night. As he told me about Rhodesia and his studies in animal science, he was, I decided, incredibly good-looking. Much taller than me, he had short-cropped hair and a fuzz of beard along the line of a deep-set jaw. At nineteen he was two years my junior. He had a delightful sense of humor that made me laugh out loud. As we parted ways that night, the party thinning out as dawn approached, he invited me to a birthday party the following week. I made no hesitation in saying yes and hurried out of the door before he could change his mind.

On the day of the party, Pat picked me up at the hotel lobby. When he arrived, I was in my room upstairs, blow-drying my hair. I checked myself in the mirror—I had spent two years living in London and I considered myself something of a fashionista—and, when I was satisfied, went down to meet him.

The figure waiting in the lobby did not look like the tall champion I had met at the party. I stopped dead on the staircase and simply stared. It was Patrick Retzlaff, all right, but surely not the Patrick Retzlaff who had asked me out. His suit was at least three sizes too small and seemed to constrict him in all the wrong places. His feet, meanwhile, were showing through a pair of oversize, scuffed cowboy boots that had clearly seen better days. I looked at him in horror and my instinct was to slowly inch away, but Pat had already caught my eye. Perhaps I could feign illness. A migraine. Food poisoning. Anything to let him down gently. I did not know if I could be seen with a man who was so badly dressed.

My mind was wheeling, grappling to come up with some excuse, when suddenly there was a commotion in the bar on the opposite side of the hotel reception area. Pat and I turned to see what was going on. At the bar, a drunken and abusive man was bearing down upon a student much smaller and slighter than himself. There was a sickening crunch as the man’s fist connected with the student’s face.

Before I knew what was happening, Patrick—constricted by his ugly, ill-fitting suit—was barreling into the bar. In seconds, he had put himself between the student and the overbearing man. Lifting a big hand, strangled by the cuff of his suit, he pushed the drunk off. The drunk reeled back against the bar, and, beneath him, the student scrabbled out of the way.

When he had made sure the student was all right, Pat turned and made his way back out of the bar. His hand was dripping with blood, his palm a scarlet swirl where fragments of broken glass had raked across it. He didn’t seem to notice until my eyes lingered on it and, when he did, he simply wiped himself clean up and down his suit.

Pat was wearing the biggest, broadest grin on his face.

“So,” he said, “are we still going to that party?”

All thoughts of migraines and food poisoning had evaporated. Already, I knew that this was the man for me.

It was a wonderful birthday party, but more wonderful for letting me get to know Pat. We spent most of the night simply talking. Pat had come to South Africa on a scholarship, but his heart belonged in the old British colony of Rhodesia, and it was to Rhodesia that he planned to return, to take up a position on an agricultural research station. At the time, Rhodesia was more than a decade deep into a civil war. Following the British prime minister Harold Macmillan’s famous “Wind of Change” speech in 1960, Britain had begun a process of granting independence to her African colonies—but, by 1965, it had become clear that Britain would not grant Rhodesia her independence with anything other than a universal franchise. A policy like that would mean that every man and woman had exactly the same right to vote, irrespective of color or level of education, and this was deemed unacceptable by the Rhodesian government, who wished to preserve its present order, with fifty seats in parliament reserved for whites and fourteen for blacks. That system would have maintained a largely white parliament, in direct contrast to the makeup of the country, in which only 10 percent of the population was white.

In 1965, Rhodesia’s prime minister Ian Smith made a Unilateral Declaration of Independence; Rhodesia became independent, yet was not acknowledged as such by Britain. The UDI triggered the onset of the bitter bush war that had been raging ever since. I could not imagine what it was like to grow up in a country at war with itself, but for Pat it was all he had known. The Rhodesian army was locked in conflict with black insurgents led by a man named Robert Mugabe, among others, and a guerrilla war was being fought across the country. This was not war as I recognized it, but a succession of sudden conflicts, terror attacks, and violent reprisals, and many men on both sides of the divide were losing their lives. Rhodesia was in a state of stalemate, and as soon as he graduated from university, Pat would have to take up a gun and join the fray.

He told me all about that, but most of all, he told me about his horses.

I had never met a man as in love with horses and animals as Pat. He came from a long line of horse lovers. His maternal great-grandfather was the Baron Moritz Hermann August von Münchausen, an officer in the Prussian army who married an American heiress and built an enormous castle in Bokstadt, Germany. It was there that he founded a stable for breeding Thoroughbreds and became famous across Europe for producing champions. The most famous horse the baron had owned was named Hannibal, which he had bought for a great deal of money in those days, and whose skeleton, Pat told me, could still be seen in a Frankfurt museum.

Pat had inherited his family’s ancestral love and skill with horses through his father, Godfrey, who had grown up in Tanzania and moved with his family to Rhodesia in 1965, just before UDI. In Rhodesia, Godfrey became the manager at a cattle ranch in the southwest of the country, and he would spend every day in the saddle, cantering around the eighty thousand acres of bush. His favorite horse—and the one that, even into his old age, he would always vividly remember—was an Arabian stallion named Paul, after both his grandfather and his eldest son. Paul the stallion liked nothing more than to drink beer and would let nobody except Godfrey ride him. Over the years, many bets were placed on this, with cocksure young horsemen eager to prove their worth by climbing into the saddle—but Godfrey always won. With a little help from his friends, Paul, it seemed, could make his own beer money.

With family like that, it was only too clear that Pat would devote his life to horses—and, even on that very first night, I knew that it was so. And there was one horse in particular who had changed Pat’s life, one horse who had been with him since he was a boy, one horse to whom he would always keep returning.

Her name, he told me, was Frisky.

In 1970, Rhodesia was five years into her civil war—but life, with all its loves, passions, and deaths, still went on. Pat was thirteen years old and on his way home from the school where he boarded. It was a year before his mother would tragically pass away from cancer, and he thought of nothing but running wild on the family farm. He had chickens and cattle of his very own, and would spend the holidays on horseback riding the farm horses, including his father’s chestnut gelding, Bridle.