Полная версия

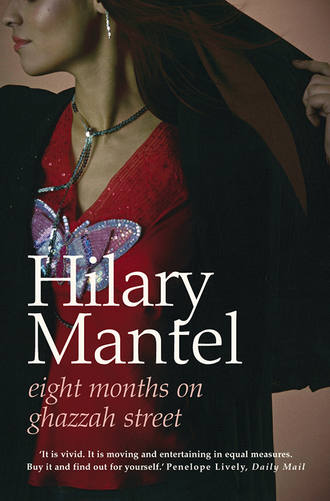

Eight Months on Ghazzah Street

‘They’re doubling my salary,’ he said flatly.

‘What?’

‘You heard.’

She turned away and bent over the tea-chest again, cleanly stabbed by avarice, like a peach with a silver knife.

‘We could be in and out within three years,’ he said. ‘Your salary is paid in riyals, tax-free. All you need out of it is your day-to-day living expenses and you can bank the rest where you like, in any currency you like. Turadup are offering free housing, a car allowance, paid utilities, yearly leave ticket, school fees – though of course –’

‘That would be plain greedy,’ she said, ‘having children so that you could get their school fees paid.’

‘Pollard did say –’ He looked at her in slight anxiety. ‘He said that his only reservation was how you’d settle in. As you’ve been a working woman.’

‘I won’t be able to work?’

‘Unlikely, he thinks.’

‘Well, if you’re going to earn all that money, I’m sure I can occupy myself. After all, it’s not for ever, is it?’

‘No, it’s not for ever. We should think of it as a chance for us, to build up some security—’

‘Will you pass me those salad bowls?’

Andrew was silent. He passed them, one by one. Why, really, should she share his vision of their future? She had come to Africa at her own behest, a single woman, one of the few recruited for her line of work. She had lived alone before they met; for three nights in succession, he had sat by himself, seemingly disconsolate, on a corner stool in the bar of an expatriate club, not even looking her way, but concentrating hard; until she had asked him to go home with her. She had fed her dog, and then cooked eggs for them, and asked him what he wanted out of life. Later, in the sagging double bed with which her government bungalow was furnished, he had lain awake while she slept, wishing furiously for her to act and understand; and although it had taken a little time to work, within a matter of weeks she had turned to him and said, ‘We could get married if that’s what you want.’

So perhaps, too, he should have wished her into suggesting Saudi Arabia; then she would have known it was her own decision. But from what he had heard it was a part of the world in which women’s decisions did not operate. He made a leap of faith: it will be all right, I know it will. ‘Frances,’ he said, ‘we won’t go unless you want to.’

She slotted a wrapped teacup into place. ‘I want to.’

It had been raining, earlier that day, and there was a heavy, animal scent of drenched earth and crushed flowers. In the kitchen their housemaid, Elizabeth, was washing glasses – pointless really as they would soon be crated up – and they could hear the separate clink that each one made as she put it down on the draining-board. The dogs and cats were coming in to be fed, wandering to the back door to wait around, like the Victorian poor. ‘I really think we ought,’ Andrew said.

‘In point of fact, I don’t think we’ve anywhere else to go.’ She picked up a broad felt marker and daubed their name on the side of the tea-chest, SHORE, FRAGILE. GABORONE – LONDON.

‘No,’ Andrew said. ‘No point.’

She crossed out LONDON, wrote JEDDAH. Another pang stabbed her, as sharp as the first. She imagined herself already in Saudi, a discreet teetotal housewife, homesick for this place that was not home in another place that was not home. It was almost dark now; the air was cooling, the sun dipping behind the hill. ‘What was Jeff Pollard doing, recruiting you? I thought he was trying to persuade everybody what a grand life it was as a freelance consultant?’

‘Well, it can’t be such a grand life, because he’s just signed up with Turadup himself. He’s going to manage their Jeddah business; he’s had experience out there, of course.’

‘So you mean you’ll be working with him?’

‘There is that tiny drawback.’

‘I hope we don’t end up living near him as well.’

‘They do pay for your housing, so it’s probably a case of taking what you’re given.’

‘That’s fine,’ she said, ‘but just try to ensure that what we’re given doesn’t include Pollard. Do you think they’ll all be like him?’

‘He’s a type. You get them everywhere. But Parsons isn’t like that.’

‘I suppose he’s another type.’

‘Yes, you’d know the one. Genial old duffer. Safari suit, doing the African bit. Two sons at medical school, showed me their photographs. His wife’s called Daphne.’

‘And did he show you a photograph of her?’

‘He didn’t, come to think of it.’

‘Perhaps he thought it would over-excite you.’

‘When he asks you what you want to drink, he says, “Name your poison.”’

‘I see. Weybridge abroad.’

‘Melbourne, I think. He keeps a place in the Cotswolds though. He’s been with Turadup for twenty years. He’s a shareholder. Pollard says he’s a millionaire. Anyway, he seems very enthusiastic about this building. About the whole scene in Jeddah. He says it’s a very stimulating place to work if you’re in the construction business.’ He paused. ‘I’ll tell you what he said exactly.’

‘Go on.’

Andrew bit his lip. ‘He said, “I have witnessed the biggest transportation of ready-mixed concrete in the history of the human race.”’

‘I’d like to witness a large gin. Let’s celebrate.’

‘We’re late,’ said the man across the aisle. She jerked out of her doze; she’d not realized, at first, that he was speaking to her.

‘Are we?’ She consulted her watch.

‘It’s always late,’ the man said tetchily. ‘Of course, if you fly Saudia, they’re always late as well.’

‘Do you go often to Jeddah?’

‘Too often. The Saudia flight’s supposed to take off at twelve-thirty, but it never does. Not in my experience. I suppose the staff are having prayers. Bowing to Mecca, and so forth.’

‘How long do prayers last?’

‘As long as it takes to inconvenience you totally,’ the man said. ‘I can tell you’ve never been in the Kingdom. Noon is movable, you see. Noon can very well be at twelve-thirty. Nothing’s what it says it is.’

Oh dear, a philosopher, she thought. She might as well put on her Walkman. She leaned down to inch out her bag from under the seat in front, and as she groped for it she felt his eyes on the back of her neck. ‘Nurse, are you?’ he inquired.

‘No.’

‘What are you doing out there then?’

‘I’m going to join my husband.’ She filled in the details again, aware that she was more polite in the air than she was on the ground: the six years in Africa, and now Turadup, and the new ministry building; aware too that as soon as she had said ‘husband’, the slight interest he had taken in her had faded completely.

‘Pity,’ he said. ‘We,’ he indicated his cohorts, ‘are stopping at the Marriot. I thought if you’d been a nurse we could have had dinner. Of course, I’m not sure if they let them out nowadays. I think they’ve got rules now that they all have to be locked in their own quarters by nine at night. It’s after that Helen Smith business.’

‘Oh, that.’

‘It was a damn funny business, if you ask me. That Dr Arnott, the chap that lived in the flat she fell out of…and that wife of his, Penny wasn’t it…and the British Embassy? You can’t tell me it wasn’t a cover-up.’

‘I wouldn’t try, I’m sure.’

‘It stinks.’

‘I’m sure you’re right.’

‘You find a young girl dead outside a high-rise block, after a wild party – you ask yourself, did she fall or was she pushed? Take it from me, it’s a funny place, Jeddah. Nobody knows the half of what goes on. You work?’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I’m a cartographer.’

‘Oh well, you’re redundant. They don’t have maps.’

‘They must have.’

‘Too bloody secretive to have maps. Besides, the streets are never in the same place for more than a few weeks together.’

‘They move the streets?’

‘Certainly do. They’re always building, you see, money no object, but they don’t think ahead. They build a hospital and then decide to put a road through it. Fancy a new palace? Out with the bulldozer. A map would be out of date as soon as it was made. It would be waste paper the day it was printed.’

‘But in a way it must be quite – exhilarating?’

He gave her a withering look. ‘If you like that sort of thing.’ He turned away, back to his companion. ‘Have you got those end-of-year projections?’ he asked. ‘I really do wonder how Fairfax is doing in Kowloon, don’t you? I don’t believe they should ever have sent him. Trouble with Fairfax, he’s got no credibility. They treat him like some bit of a kid.’

Frances closed her eyes again. Drifting, she caught bits of their conversation: jargon, catchphrases. At home, at her widowed mother’s house in York, she had been reading books about her destination. Despite her scepticism, her better knowledge, their contrived images lingered in her mind: black tents at sunset, the call of the muezzin in clear desert air: the tang of cardamom, the burnish of sharp-snouted coffee-pots, the heat of the sand. ‘We’re building up the infrastructure,’ said the man who despised Fairfax. Infrastructure was a word she had heard on Andrew’s lips; he had grown fond of it. It seemed that when oil was discovered in the Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia had no infrastructure, but that it had one now: roads, schools, hospitals, factories, mines, market-gardens and chicken farms, airports and squash courts, telephones and filling stations, cold-stores and police stations, take-away food shops, and the ten-pin bowling facilities at the Albilad Hotel. All this she knew from her reading, because after the romantic travellers’ tales came Jeddah: A Businessman’s Guide. The black tents of the Bedu have been replaced by aluminium shacks. Air-conditioning is universal. Gazelles are hunted from the backs of pick-up trucks.

I must like it, she thought. I shall try to like it. When everyone is so negative about a place you begin to suspect it must have some virtues after all. ‘No alcohol!’ people say, as if you’d die without it. ‘And women aren’t allowed to drive? That’s terrible.’ There are lots of things more terrible, she thought, and even I have seen some of them. She dozed.

A touch on her arm woke her. It was the steward. ‘We’ll be beginning our descent in half an hour. I’m just doing a final drinks round. Another cognac?’

‘Keep the young lady sober,’ the businessman advised. ‘She’s got the customs to face, and it’s her first time. They go through everything,’ he told her. ‘I hope you haven’t got anything in your suitcase that you shouldn’t have?’

‘I haven’t got a bottle of whisky or a shoulder of pork. What else will they be looking for?’

‘Where do you buy your underwear?’

‘What?’

‘Marks & Spencer, you see, they call them Zionists. You have to cut the labels out. Didn’t anybody tell you that? And they look at your books. This colleague of mine, when he was last in the Kingdom, he had his book of limericks confiscated. It had this drawing on the cover, a woman, you know.’ He gestured in the air, describing half-circles. ‘Naked, just a line-drawing. Chap said he hadn’t noticed.’

‘That seems unlikely,’ she said. She added, to herself, ‘a friend of yours’.

‘It’s all unlikely. Even when you’ve been coming in and out for years, you never know what they’re going to be looking for. Our rep in Riyadh, he lives there, he should know. But then last year when he was coming back after his summer holidays they took away his Test Match videos. All his recorded highlights. Oh, they said he could have them back, when the customs had had a careful look. But he never went for them. He couldn’t take the hassle.’

‘Poor man.’

‘You’ve not got any art books, have you? Rubens or anything? Because they can be very funny about art.’

‘It’s unIslamic,’ Frances said, ‘to worship the human form. It’s idolatry.’ The man stared at her.

‘So I can’t tempt you?’ the steward asked. He peered into his empty ice-bucket. ‘Gentlemen, don’t leave any miniatures down the seat pockets, please, we don’t want our ground-staff flogged.’ He looked down at Frances. ‘We’re relinquishing this route next year,’ he said. ‘Give it to British Caledonian and welcome, that’s what I say. No more to drink then?’ He prepared to abandon her, move away. Sleeping executives stirred now, dribbling a little on to their airline blankets. There was a sound of subdued laughter; briefcases intruded into the aisles. The steward relented. He leaned over her seat. ‘Listen, if anything goes wrong, if by some mischance hubby’s not there, don’t hang about, don’t speak to anybody, get straight in our airline bus and come downtown with us to the Hyatt Regency. You check in, and I’ll look after you, and he can come and find you in the morning.’

‘Oh, I’m sure he’ll be there,’ she said. Or someone will. Jeff Pollard. At least he’d be a familiar face. ‘I’ve got numbers to ring, in case anything goes wrong. And I could take a taxi.’

‘You can’t take a taxi. They won’t carry you.’

She thought of that cheese, that people say French taxi-drivers won’t let in their cabs. ‘What, really not?’

‘It’s bad news, a man picking up a strange woman in a car. They can gaol you for it.’

‘But he’s a taxi-driver,’ she said. ‘That’s his job, picking up strange people.’

‘But you’re a woman,’ the steward said. ‘You’re a woman, aren’t you? You’re not a person any more.’ Doggedly, courteously, as if their conversation had never occurred, he reached for a glass from his trolley: ‘Would you like champagne?’

Soon, the crackle from the P/A system: Ladies and gentlemen, we are now beginning our descent to King Abdul Aziz International Airport. Those seated on the left-hand side of the aircraft will see below you the lights of Jeddah. Kindly fasten…kindly extinguish…(And to the right, blackness, tilting, and a glow of red, the slow fires that seem to ring cities at night.) We hope you have enjoyed, we hope to have the pleasure…we hope…we hope…and please to remain seated until the aircraft is stationary…

Half an hour later she is inside the terminal building. The date is 2 Muharram, by the Hijra calendar, and the evening temperature is 88°F; the year is 1405.

Muharram

1

Ghazzah Street is situated to the east of Medina Road, behind the King’s New Palace, and in the district of Al Aziziyya; it is a small street, which got its name quite recently when street names came into vogue, and a narrow street, made narrower by the big American cars, some of them falling to pieces, which its residents leave parked outside their apartment blocks. On one side is a stretch of waste ground, full of potholes; water collects in them when, three or four times a year, rain falls on the city. The residents complain about the mosquitoes which breed in the standing pools, but none of them can remember whether there was ever a building on the waste ground; no one has been in the area for more than a couple of years. Many of the tenants of Ghazzah Street still keep some of their possessions in cardboard boxes, or in shipper’s crates bearing the names of the removal and transport companies of the subcontinent and the Near East. They are from Pakistan or Egypt, salesmen and clerical workers, or engaged in a mysterious line of work called Import-Export; or they are Palestinians perhaps, or they are picking up a family business that has been bombed out of Beirut.

The district is not opulent, not sleazy either; the small apartment blocks, two and three storeys high, are walled off from the street, so that you seldom catch sight of the residents, or know if there is anyone at home; women and babies are bundled from kerb to car, and sometimes schoolchildren, with grave dark faces, trail upstairs with their books in the late afternoon. No one ever stands and chats in Ghazzah Street. Neighbours know each other by sight, from glimpses on balconies and rooftops; the women speak by phone. There are a couple of offices, one of them a small forgotten offshoot of the Ministry of Pilgrimages, and one of them belonging to a firm which imports and distributes Scandinavian mineral water. Just around the corner on Al-Suror Street, there is a mosque, its dome illuminated at dusk with a green neon light; at the other end of the street, in the direction of the palace of Prince Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz, there is a small shop which sells computer supplies and spare parts.

At the moment Ghazzah Street is about a mile and a half from the Red Sea, but in this place land and sea are in flux, they are negotiable. So much land has been reclaimed, that villas built a few years ago with sea views now look out on the usual cityscape of blank white walls, moving traffic, building sites. On every vacant lot in time appears the jumble of brownish brick, the metal spines of scaffolding, the sheets of plate glass; then last of all the marble, the most popular facing material, held on to the plain walls behind it with some sort of adhesive. From a distance it lends a spurious air of antiquity to the scene. When the Jeddah earthquake comes – and it will come – all-seeing Allah will observe that the buildings are held together with glue; and he will peel the city apart like an onion.

The sea itself, sometimes cobalt in colour and sometimes turquoise, has a flat, domestic, well-used appearance. Small white-collared waves trip primly up to the precincts of the desalination plant, like a party of vicars on an industrial tour. The lights of the royal yacht wink in the dusty evenings; veiled ladies splash on the foreshore in the heat of the day. Benches, placed by the municipality, look out to sea. Around the bay sweeps an ambitious highway, designated The Corniche; now known as Al Kournaich, or the Cornish Road. Public monuments line the sea-front, and crown the intersections of the endless, straight and eight-lane public highways; bizarre forms in twisted alloys, their planes glistening in the salt and smog air.

On Fridays, which are days for rest and prayer, families picnic around these monuments, black figures in a tundra of marble; stray cats breed on their slopes. The sun strikes from their metal spokes and fins; towering images of water-jugs, sea-horses, steel flowers; of a human hand, pointing to the sky. Vendors sell, from roadside vans, inflatable plastic camels in purple, orange and cerise.

If you walk, suitably dressed, along the Corniche, you can hear the sea-wind howl and sigh through the sewers beneath the pavements. It is an unceasing wail, modulated like the human voice, but trapped and far-away, like the mutinous cries of the damned. ‘The people in hell remain alive,’ says a Muslim commentator. ‘They think, remember and quarrel; their skins are not burned, but cooked, and every time they are fully cooked, new skins are substituted for them to start the suffering afresh.’ And if you pick your way, with muttered apologies, through the families ensconced on the ground, on the carpets they have unloaded from their cars, you will see the men and women sitting separately, one hunched group garbed in black and one in white, and the children playing under a servant’s eye; the whole family turned to the sea, but the adults rapt, enthralled, by the American cartoons they are watching on their portable TV. A skin-diver, European, lobster-skinned, strikes out from an unfrequented part of the coastline for the coral reef.

Back on the road the teenaged children of the Arab families catcall and cruise, wrecking their Ferraris. Hotrodding, the newspapers call it; the penalty is flogging. A single seabird hovers, etched sharp and white against the sky; and a solitary goat-faced Yemeni, his tartan skirts pulled up, putters on a clapped-out scooter in the direction of Obhur Creek. The horizon is a line of silver, and beyond it is the coast of the Sudan; enclosed within it is the smell of the city’s effluent, more indecipherable, more complicated than you would think. At the weekend the children are given balloons, heart-shaped and helium-filled, which bob over the rubble and shale. On the paving stones at your feet are scrawled crude chalk drawings of female genitalia. Inland, wrecked cars line the desert roads, like skeletons from some public and exemplary punishment.

Whatever time you set out for Jeddah, you always seem to arrive in the small hours; so that the waste of pale marble which is the arrivals hall, the rude and silent customs men turning over your baggage, seem to be a kind of dream; so that from each side of the airport road dark and silent spaces stretch away, and then comes the town, the string of streetlights dazzling you, the white shapes of high buildings penning you in; you are delivered, to some villa or apartment block, you stumble into a bathroom and then into bed – and when you wake up, jerked out of a stuporous doze by the dawn prayer-call, the city has formed itself about you, highways, mosques, palaces and souks; grey-faced, staggering a little, you stumble into the rooms you are going to inhabit, draw back the curtain or blind and – with a faint smell of insecticide in your nostrils – confront the wall, the street, the tree with its roots in concrete and six months’ accumulation of dun-coloured dust on its leaves; wake up, wake up, you have arrived. The first night has passed now, the severance is complete; the journey is a phantom, the real world recedes.

Andrew brought coffee. To her surprise, she felt chilly. He had always been bothered by the heat, and so it was his habit now to sleep with the air conditioners on, rattling and banging away all night. No wonder she hadn’t slept properly. She had dreamt she was in a railway siding, with the endless shunting, and the scrape of metal wheels.

Andrew was already dressed, buttoning his white shirt, plucking a tie from inside the wardrobe door. His muddy overalls and his safety helmet would be elsewhere, she supposed, although he had said in his letters that he would spend more time shuffling papers than he would at the site; ‘Pity you couldn’t come at a weekend,’ he said. ‘I feel bad about going off and leaving you to it.’

‘What time is it?’ She shivered.

‘Six-thirty. Back at three. Sometimes I have a siesta and go into the office for the early evening, but I’ll not do that today. We can go shopping. I’ll show you round. Are you hungry?’

‘No. Yes, a bit.’

‘There’s stuff in the fridge, you’ll find it. Steak for dinner.’

So everything was ready for her, as he had said it would be. When she had blundered through the rooms, an hour ago, she saw pale airy spaces, a vast expanse of beige and freshly hoovered carpet. Pieces of furniture, new, smelling of plastic sheeting, stood grouped here and there; a dozen armchairs, a gleaming polished expanse of table-top, a white, antiseptic bathroom. Quite different from the old life: the donkey boiler at the back of the house, and the tin roof, and the sofas and beds which had gone from family to family.

‘I may have been dreaming,’ Andrew said, ‘but did you go on a pre-dawn tour?’

‘I’m sorry if I woke you.’

‘The prayer call wakes me anyway. What do you think of the flat? There was a house, it was on a compound with some of the Ministry of Petroleum people, but Jeff lives there – you said you didn’t want him for a neighbour. It’s taken now anyway. You don’t get a lot of choice, Turadup has to rent what it’s told. It’s a big source of income for Saudi families, letting houses to expats.’

‘Who owns these flats?’

‘I think it’s the Deputy Minister’s uncle.’

‘Who paid for all the stuff? The new furniture?’

‘The company. They’ve redecorated the whole place as well.’

‘They’re looking after us. It’s not like Africa.’

‘Well, in Africa nobody cared whether you came or went. If you found it too tough you just drifted off.’

‘But here they care?’

‘They try to keep you comfortable. The thing is it’s not a very comfortable place. Still,’ he said, recollecting himself, ‘the money’s the thing.’

Frances pushed back the sheets, swung her legs out of bed. ‘One thing that seems rather odd…last night when we arrived I saw those big front doors, I thought there’d be a shared hallway, but you brought me in through a side door, straight into our kitchen. I’ve found that side door, but where’s our front door? How do I get into the hall?’