Полная версия

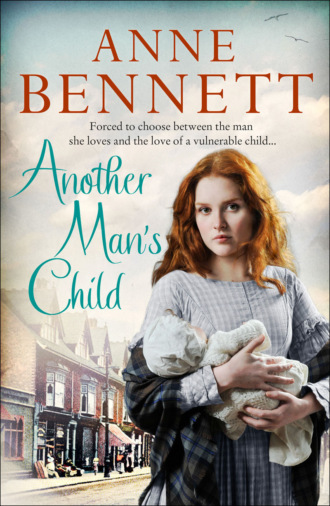

Another Man’s Child

‘Sorry about your mother and all,’ Andy said. ‘But I can’t help being pleased that you haven’t your own bull.’

‘Why on earth would that matter to you one way or the other?’ Celia asked in genuine surprise.

‘Because this way I get a chance to talk to you,’ Andy declared.

Celia blushed crimson. ‘Hush,’ she cautioned.

‘What?’ Andy said. ‘We are doing no harm talking.’ And then, seeing how uncomfortable Celia was, he went on, ‘Is it because I’m a hireling boy and you a farmer’s daughter?’

Celia’s silence gave Andy his answer and he said, ‘That’s hardly fair. My elder brother Christie will inherit our farm and after my father paid out for my two sisters’ weddings last year he said I had to make my own way in the world. He has a point because I am twenty-one now and there are two young ones at home for them to provide for and I would have to leave the farm eventually anyway.’

‘I know,’ Celia said. ‘That’s how it is for many. Tom will have the farm after Daddy’s day.’

‘Have you other brothers?’

‘The next eldest to him went to America where we have an aunt living.’

‘It’s handy to have a relative in America.’

‘It is if you want to go there, I suppose,’ Celia said.

‘You haven’t any hankering to follow him then?’

Celia shook her head vehemently. ‘Not me,’ she said. ‘My sister Norah is breaking her neck to go, but Mammy is making her wait until she’s twenty-one.’

‘And is that far away?’

Celia sighed. ‘Not far enough,’ she said. ‘It’s just a few months and I will so miss her when she’s gone.’

‘Have you no more brothers and sisters?’

‘Yes,’ Celia said. ‘Dermot is over three years younger than me, so he is nearly fifteen and left school now and then there is Ellie who is nine and Sammy who is the youngest at seven.’

‘Not much company for you then?’

Celia shook her head. ‘I’d say not,’ and then she added wryly, ‘Mind you, I might be too busy to get lonely for I will have to do Norah’s jobs as well as my own.’

‘You can’t work all the time,’ Andy said. ‘Do you never go to the dances and socials in the town?’

Celia shook her head.

‘Why on earth not?’

‘I don’t know why not,’ Celia admitted. ‘It’s just never come up, that’s all.’

‘Well maybe you should ask about it?’ Andy said. ‘No wonder your sister can’t wait to go to America if she is on the farm all the days of her life. There’s a dance this Saturday evening.’

‘And are you going to it?’

‘I am surely,’ Andy said. ‘Mr Fitzgerald told me about it himself. He advised me to go and meet some of the townsfolk and it couldn’t be more respectable, for its run by the church and I’m sure the priest will be in attendance.’

Celia knew Father Casey would have a hand in anything the Catholic Church was involved in – particularly if it was something to do with young people, who he seemed to think were true limbs of Satan, judging by his sermons. And yet, despite the priest’s presence there, she had a sudden yen to go, for at nearly eighteen she was well old enough and she wondered why Norah had said nothing about it. Tom attended the dances but she never went out in the evening and neither did Norah, not even to a neighbour’s house for a rambling night, which was often an impromptu meeting, spread by word of mouth. There would be a lot of singing or the men would catch hold of the instruments they had brought and play the lilting music they had all grown up with and the women would roll up the rag rugs and step dance on the stone-flagged floor. She had never been to one, but before Maggie died the Mulligans had had rambling nights of their own and she remembered going to sleep with the tantalising music running round in her head. She didn’t say any of this to Andy for she had spied her father making his way towards them across the field and saw him quicken his pace when he saw his daughter in such earnest conversation with the hireling boy.

So Dan gave Andy a curt nod of the head as a greeting and said, ‘Bring him through into the field.’ And as Andy led the bull through the gate Dan said to Celia, ‘You go straight back to the house. This is no place for you anyway.’ And Celia turned and without even looking at Andy she returned to the farmhouse, deep in thought.

TWO

‘Why do we never go to the socials or the dances in the town?’ Celia said as she and Norah washed up together in the scullery.

Norah shrugged. ‘What’s brought this on?’

‘Just wondered, that’s all,’ Celia said. ‘Heard a couple of girls talking about it in the town Saturday.’

‘Did you?’ Norah said in surprise. ‘I never heard anyone say anything and I’d have said we were together all the time.’ Her eyes narrowed suddenly and she said, ‘It wasn’t that hireling boy put you up to asking?’

‘He has got a name, that hireling boy,’ Celia said, irritated with Norah’s attitude. ‘He’s called Andy McCadden and he didn’t put me up to anything. He asked if I was going to the dance and I said, no, that we never go.’

‘What was it to him?’

‘God, Norah, he meant nothing I shouldn’t think,’ Celia said. ‘Just making conversation.’

‘Well you were doing your fair share of that,’ Norah said. ‘I watched you through the window, chatting together ten to the dozen. Very cosy it looked.’

‘What was I supposed to do, ignore him?’ Celia asked. ‘I was taking him to find Daddy and he was leading a bull by the nose. Not exactly some sort of romantic tryst. Anyway, why don’t we ever go to the dances and the odd social?’

‘Well Mammy would have thought you too young until just about now anyway.’

‘All right,’ Celia conceded. ‘But what about you? You’re nearly twenty-one.’

‘I know,’ Norah said and added with a slight sigh, ‘I went with Maggie a few times; maybe you were too young to remember it. When she took sick and then died I had no desire to go anywhere for some time and then we were in mourning for a year and so I sort of got out of the way of it and anyway I didn’t really want to go on my own.’

‘Tom goes.’

‘He’s a man and not much in the way of company,’ Norah said. ‘Anyway he’d hardly want me hanging on to his coat tails. After all he went there hunting for a wife.’

‘Golly!’ Celia exclaimed. ‘Did he really?’

‘Course he did,’ Norah said assuredly. ‘No frail-looking beauty for him, for he was on the lookout for some burly farmer’s daughter, with wide hips who can bear him a host of sons and still have the energy to roll up her sleeves and help him on the farm.’

Celia laughed softly. ‘Well he hasn’t, has he?’ she said. ‘Though no one said a word about it, everyone knows he’s courting Sinead McClusky and she is pretty and not the least bit burly.’

‘Maybe not but you couldn’t describe her as delicate either and she is a farmer’s daughter.’

‘What about love?’

‘You’re such a child yet,’ Norah said disparagingly. ‘What does Mammy say? “Love flies out of the window when the bills come in the door.” Tom will do his duty, as you probably will too in time.’

‘Me?’ Celia’s voice came out in a shriek of surprise.

‘Ssh,’ Norah cautioned. ‘Look, Celia, it’s best you know for this is how it is. If I stayed here and threw Joseph over, apart from the fact my name would be mud, Daddy might feel it in my best interests to get me hooked up with someone else and of his choosing. This might well happen to you and it isn’t always in our best interests either, but it’s done to increase the land he has or something of that nature. And it will be no good claiming you don’t love the man they’re chaining you to for life, because that won’t matter at all.’

‘What about Mammy?’ Celia cried, her voice rising high in indignation. ‘Surely she wouldn’t agree to my marrying a man I didn’t love?’

Norah shrugged. ‘Possibly the same thing happened to her and it’s more than likely she sees no harm in it.’

‘Well I see plenty of harm in it,’ Celia said. ‘You said something like this before, but this has decided me. I shall not marry unless for love and no one can make me marry someone I don’t want.’

‘Daddy might make your life difficult.’

Celia shrugged. ‘I can cope with that if I have to.’

‘Well to find someone to take your fancy,’ Norah said, ‘you need to go out and have a look at what is on offer, for I doubt hosts of boys and young men will be beating a path to our door. And so I think we should put it to Mammy and Daddy that we start going out more and the dance this Saturday is as good a way to start as any. You just make sure you don’t lose your heart to a hireling man.’

Celia expected some opposition to her and Norah going to the dance that Saturday evening when Norah broached it at the dinner table the following day, but there wasn’t much. Peggy in fact was all for it.

‘Isn’t Celia a mite young for that sort of carry-on?’ Dan muttered.

Celia suppressed a sigh as her mother said, ‘She is young, I grant you, but Tom will be there and he can take them down and bring them back and be on hand to disperse any undesirable man who might be making a nuisance of himself.’

‘And I will be there to see no harm befalls Celia,’ Norah said. ‘It isn’t as if I’m new to the dances – I used to go along with Maggie.’

Peggy sighed. ‘Ah yes, you did indeed, child,’ she said, a mite sadly. She had no desire to prevent them from going dancing, particularly Norah, for if she wasn’t going to marry Joseph maybe she should see if another Donegal man might catch her heart and then she might put the whole idea of America out of her head.

And so with permission given, the girls excitedly got ready for the dance on Saturday. They had no dance dresses as such but they had prettier dresses they kept for Mass. They were almost matching for each had a black bodice and full sleeves. Celia’s velvet skirt was dark red, Norah’s was midnight blue. Celia had loved her dress when Mammy had given it to her newly made by the talented dress maker and now she spun around in front of the mirror in an agony of excitement at going to her first dance.

‘Aren’t they pretty dresses?’ Celia cried.

‘They are pretty enough I grant you,’ Norah said. ‘It’s just that they are so long.’

‘Long?’

‘Yes, it’s so old fashioned now to have them this long. It is 1920 after all.’

‘Let me guess?’ Celia said. ‘I bet they’re not this length in America.’

‘No they aren’t,’ Norah said. ‘Men over there don’t swoon in shock when they get a glimpse of a woman’s ankle.’

‘How do you know?’ Celia demanded. ‘That’s not the sort of thing Jim would notice and he certainly wouldn’t bother to write and tell you.’

‘No he didn’t,’ Norah admitted. ‘But Aunt Maria did. And she said that the women wear pretty button boots, not the clod-hopping boots we have.’

‘Well pretty button boots would probably be little good in the farmyard,’ Celia pointed out. ‘And really we should be grateful for any boots at all when many around us are forced to go about barefoot.’

‘I suppose,’ Norah said with a sigh. ‘Anyway we can do nothing about either, so we’ll have to put up with it. Now don’t forget when you wash your hair to give it a final rinse with the rainwater in the water butt to give it extra shine.’

‘I know and then you’re putting it up for me.’

‘Yes and you won’t know yourself then.’

Norah knew Celia had no idea just how pretty she was with her auburn locks, high cheekbones, flawless complexion, large deep brown eyes and a mouth like a perfect rosebud. She knew her sister would be a stunner when she was fully mature. She herself looked pretty enough, although her hair was a mediocre brown and her eyes, while large enough, were more of a hazel colour.

She sighed for she wished her mother would let her buy some powder so she could cover the freckles that the spring sunshine was bringing out in full bloom on the bridge of her nose and under her eyes. However, she had heard her mother say just the other day that women who used cosmetics were fast and no better than they should be.

She imagined things would be different in America, but she wasn’t there yet and Celia, catching sight of Norah’s forlorn face, cried, ‘Why on earth are you frowning so?’

Norah shrugged and said, ‘It’s nothing. Come on, Tom will be waiting on us and you know how he hates hanging about.’

Celia did. Her brother wasn’t known for his patience so she scurried along after her sister.

The church hall was a familiar place to Celia and she passed the priest lurking in the porch watching all the people arriving. She greeted him as she passed and went into the hall, where her mouth dropped open with astonishment for she had never seen it set up for a dance before, with the musicians tuning up on the stage and the tables and chairs positioned around the edges of the room while still leaving enough room in there for the bar where the men were clustered around having their pints pulled, Tom amongst them. Celia knew respectable women and certainly girls didn’t go near bars though. Tom would bring them a soft drink over and Norah said that was that as far as he was concerned.

‘If you want another we shall have to go and find him,’ Norah said.

‘What d’you do if you haven’t come with a man?’ Celia asked.

Norah shrugged. ‘If you haven’t got a handy brother or male cousin it’s often safer to stay at home,’ she said.

‘Safer?’

‘Yes,’ Norah affirmed. ‘Some men are the very devil when they have a drink on them.’ And then glancing at the door she said, ‘Oh Lord. Here’s Joseph come in the door and looks very surprised to see me, as well he might be.’

Celia turned and saw Joseph’s eyes widen in surprise at seeing Norah, yet Celia saw that he was anything but displeased about it because his face was lit up in a smile of welcome. ‘I expect I will have to go and be pleasant to him,’ Norah said.

‘I’d say so,’ Celia said. ‘Look at that smile and it’s all for you. I’d say he’s really gone on you.’

‘Yes,’ Norah said. ‘I wish he wasn’t.’

‘Well he can’t help how he feels, can he?’ Celia said. ‘And anyway it’s partly your fault. You should have been straight with him about your intention to emigrate to America from the start.’

Celia saw from the reddening on Norah’s cheeks that what she had said had hit home and watched her walk across towards Joseph. Celia turned away, wondering what it would feel like to have a man smile just for her in such a way.

And then she saw Andy McCadden at the bar smiling at her in much the same way. It made her feel slightly light-headed and before she was able to recover her senses Andy was by her side and saying, ‘I thought you said you never came to the dances, Miss Celia Mulligan.’

Before answering him, Celia took a surreptitious look around. Tom, she saw, was talking to Sinead McClusky and Norah was away talking to Joseph and so she faced Andy and said, ‘We don’t. This is the first one I have been to and I wasn’t sure I would be let go and it was only because Norah was here to keep an eye on me and my brother was walking us down and back again that made Mammy say I could go.’

‘And where are your protectors now?’ Andy asked in a bantering tone. ‘Not doing their job very well, I would say. Leaving you stranded in the middle of the room without even a drink in your hand. I can remedy that at least.’

‘Oh no,’ Celia cried. ‘Really it’s all right.’

‘It’s not all right,’ Andy said. ‘I have a great thirst on me, which I intend to slake with a pint and I can hardly drink alone. I’m afraid I must insist you join with me.’

And before Celia was able to make any sort of reply to this, Andy wheeled away and left her standing there. She felt rather self-conscious and looked round to see if she could see Tom or Norah, thinking that she might have joined them, but so many people were now in the hall she couldn’t see them. And then Andy was back with a glass of Guinness in one hand and a glass of slightly cloudy liquid in the other which he held out to Celia. She didn’t take it though and, eyeing it suspiciously, said, ‘What is it?’

‘Homemade apple juice.’

‘You mean cider?’

‘No. If I meant cider I would have said cider,’ Andy said with a smile. ‘I would never offer anyone of your tender years alcohol. This is what I said it was, apple juice plain and simple, and it will do you no harm whatsoever. Take it.’

Celia had barely taken the glass from him when Norah pounced on her. She had felt guilty for leaving her to her own devices to talk to Joseph and hadn’t meant to be away so long. Now she said sharply, ‘What are you up to and what is that in that glass?’

‘I’m not up to anything,’ Celia retorted. ‘Why should you think I was? And all that’s in my glass is apple juice.’

Norah was still looking at it suspiciously and Andy put in, ‘It’s true what Miss Mulligan said. I found her looking a bit lost. I believe it is her first time at an event like this.’

Norah knew it was and that was the very reason she shouldn’t have left her high and dry as she had and so when Andy went on, ‘I was buying a drink for myself and so I offered to buy one for your sister and it is, as she said, apple juice,’ Norah couldn’t say anything but, ‘Thank you for looking after her so well, Mr …’

‘McCadden,’ Andy said, extending his hand. ‘Andy McCadden.’

‘Norah Mulligan,’ Norah felt obliged to say as she took hold of the man’s proffered hand. ‘And you have already met my sister, Celia.’

‘Yes indeed.’

‘And now you must excuse us,’ Norah said. ‘There are some people I want Celia to meet.’

Andy gave a sardonic smile as if he didn’t believe for one moment that there were people Celia had to meet but he said, ‘Of course.’ And then, as they turned away, he added, ‘Perhaps I can claim you both for a dance later?’

Celia didn’t answer for she had seen Norah’s lips purse in annoyance and then Norah answered in clipped tones, ‘We’ll have to see, Mr McCadden. I can make you no promises.’

‘There was no need to be rude to Mr McCadden,’ Celia hissed through the side of her mouth to her sister as soon as she was sure they were out of earshot of the man who was standing watching them walk across the room.

‘I wasn’t at all rude,’ Norah protested. ‘I was perfectly polite.’

‘You were stiff and awkward, like,’ Celia persisted. ‘And it wasn’t as if he did anything wrong – unless talking to me and buying me a drink is wrong. I did look round for you and Tom and couldn’t see either of you.’

‘I can’t answer for Tom, but I stepped outside with Joseph,’ Norah said. ‘After what you said, I decided to tell him once and for all about America. I thought I had strung him along enough and he deserved that I tell him the truth. He was a bit upset, wouldn’t accept it you know, so I stayed talking to him longer than I intended. I did think Tom might have checked to see you were all right and though I think Mr McCadden was pleasant enough he is not the kind of person that you should encourage. And now here’s Tom coming with a drink for each of us. Put the one McCadden brought you on the table quick before he sees it.’

‘Why? It’s only a drink, Norah.’

‘Will you do as I tell you,’ Norah hissed. ‘There are things that are not done and accepting a drink from a man unrelated to you and almost a stranger to boot is one of them. You are going the right way to make Tom tear him off in no uncertain terms for being familiar and Tom won’t care how rude he is.’

Celia thought Norah was probably right and so she slipped the drink Andy had brought her onto the table beside her just as Tom came into view, smiling jovially at the two girls. ‘Enjoying yourselves?’ he asked.

‘We’ve only just got here,’ Norah pointed out, but Celia said, ‘I think it’s quite exciting. It’s nothing like the church hall is normally.’

‘No indeed it isn’t,’ Tom said as the band struck up the music for a four-hand reel. He asked, ‘Now will you be all right? I promised Sinead a dance.’

‘Then go on,’ Norah said. ‘There are lots of people I want to introduce Celia to.’

Tom left them as Norah slipped her arm through Celia’s. ‘Come on,’ she said. ‘There really are lots of people I want you to meet, men as well as girls, and I think I can guarantee that, looking as you do, you will be up dancing most of the night and won’t give a thought to Mr McCadden.’

In a way Norah was right for Celia proved a very popular girl. She was slight in build, the sort of girl that the men she was introduced to wanted to protect, and so light on her feet as she danced the set dances and jigs and reels and polkas that she loved. Not even Father Casey looking about him with disapproval could quell Celia’s enjoyment. And yet she couldn’t get Andy McCadden quite out of her mind and every time she caught sight of him his brooding eyes seemed to be constantly fastened on her.

They lined up for the two-handed reel and Andy suddenly left the bar and joined the line with another woman. It was the sort of dance when the girls started with one partner but danced with different men in the set until they ended up back with their original partner and so at one point Celia was facing Andy. As they moved to the centre Andy spoke quietly through the side of his mouth, ‘Your sister is trying to keep us apart.’ Celia didn’t answer – there wasn’t time anyway – and the second time they came near to one another he said, ‘D’you ever walk out on Sunday afternoons?’ and the third and last time they came close he said, ‘We could meet and chat.’

Before Celia had time to digest what Andy had said, never mind reply to it, she was facing another partner and the dance went on and she was glad that she knew the dance so well and didn’t have to think much about it because her head was in a whirl with the words Andy had whispered to her. As the dance drew to a close and she thanked the man who had partnered her, she had to own that Andy was right about one thing: Norah had taken a distinct dislike to Andy McCadden and was going to do her level best to keep them apart. Celia thought she had a nerve. Norah was prepared to swan off to America, upsetting everyone to follow her dream, and she had told Celia she was too fond of trying to please people and she had to stop that and look to her own future. Now Celia wasn’t sure that Andy McCadden would be part of that future, she was a tad young to see that far ahead, but what was wrong with just being friends or, at the very least, being civil to one another? Norah didn’t have to treat him as if he had leprosy.

She was sitting at a table alone for once, a little tired from all the dancing, and she scanned the room for Tom and Norah, just in time to see Tom leading Sinead outside. Norah was nowhere to be seen and suddenly Andy was by her side again with another glass of apple juice in his hand.

‘Thank you,’ she said as she took it from him without the slightest hesitation and drank it gratefully.

‘You look as if you were in need of that,’ Andy said as he sat on the seat beside her.

‘I was thirsty,’ Celia admitted. ‘It’s all the dancing.’

‘And tired, I’ll warrant.’

‘Yes a little.’

‘That’s a pity.’

‘Why?’

‘They are playing the last waltz,’ Andy said. ‘I was going to ask you to dance with me but if you are tired …’

Celia hesitated, for she knew the last waltz was special and she shouldn’t dance it with a man she hardly knew. Andy saw her hesitation and said, ‘Or perhaps you think your brother and sister would not approve.’

Andy wasn’t to know, but his words lit a little light of rebellion in Celia’s heart. What right had Norah and Tom to judge her? All she was proposing to do was dance with a man she had spoken to a few times in open view of everyone. It wasn’t as if she was sneaking outside like Tom with Sinead, who might well be up to more than just holding hands, and she had no idea where Norah was. And so she smiled at Andy and, at the radiance of that smile, Andy felt a lurch in his stomach as if he’d been kicked by a mule.

‘I’m not that tired, Andy, and I would love to dance with you,’ Celia said.