Полная версия

Wellington: A Personal History

COPYRIGHT

William The 4th

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1997

Copyright © Christopher Hibbert 1997

Christopher Hibbert asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780586091098

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2010 ISBN: 9780007406944

Version: 2016-09-08

DEDICATION

For Pam Carpenter

With Love

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

List of Illustrations

Author’s Note and Acknowledgements

Maps

PART I • 1769–1815

1 Eton, Dublin and Angers, 1769–87

2 An Officer in the 33rd, 1787–93

3 The First Campaign, 1794–5

4 A Voyage to India, 1796–8

5 The Tiger of Mysore, 1799

6 The Governor of Mysore, 1799

7 The Sultan’s Palace, 1800–1

8 Assaye, 1802–5

9 Return to London, 1805–6

10 Kitty Pakenham, 1790–1806

11 Ireland and Denmark, 1806–7

12 Portugal, 1808

13 Board of Enquiry, 1808

14 Across the Douro, 1809

15 ‘A Whole Host of Marshals’, 1809–10

16 From Bussaco to El Bodon, 1810–11

17 Life at Headquarters, 1810–12

18 Badajoz, Salamanca and Madrid, 1812

19 Retreat to Portugal, 1812

20 From Vitoria to the Frontier, 1812–13

21 St Jean de Luz, 1813

22 In London Again, 1814

23 Paris and Vienna, 1814–15

24 Brussels, 1815

25 Waterloo, 1815

PART II • 1815–52

26 The Ambassador, 1815

27 Cambrai and Vitry, 1815–18

28 Stratfield Saye, 1818–20

29 King George IV and Queen Caroline, 1820–1

30 Husband and Wife, 1821

31 Vienna and Verona, 1822–4

32 St Petersburg and the Northern Counties, 1825–7

33 The Prime Minister, 1828–9

34 Battersea Fields and Scotland Yard, 1829

35 The Death of the King, 1829–30

36 Riots and Repression, 1830–2

37 A Bogy to the Mob, 1832

38 Oxford University and Apsley House, 1832–4

39 Lady Friends, 1834

40 The Foreign Secretary, 1834–6

41 Portraits and Painters, 1830–50

42 Life at Walmer Castle, 1830–50

43 The Young Queen, 1837–9

44 Grand Old Man, 1839–50

45 The Horse Guards and the House of Lords, 1842–50

46 Hyde Park Comer, 1845–6

47 Disturbers of the Peace, 1846–51

48 Growing Old, 1850–1

49 Last Days, 1851–2

50 The Way to St Paul’s, 1852

Footnote

Keep Reading

References

Sources

Index

Photo Section

About the Author

Praise

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

ILLUSTRATIONS

BLACK AND WHITE

Lieutenant-Colonel the Hon. Arthur Wellesley. Portrait by John Hoppner. Reproduced courtesy of The Duke of Wellington KG; photograph Courtauld Institute of Art.

Anne, Countess of Mornington. Reproduced courtesy of The Duke of Wellington KG; photograph Courtauld Institute of Art.

The Hon. William Wellesley-Pole. Portrait by John Hoppner. Reproduced courtesy of The Duke of Wellington KG; photograph Courtauld Institute of Art.

The Rev. the Hon. Gerald Valerian Wellesley. Reproduced courtesy of The Duke of Wellington KG; photograph Courtauld Institute of Art.

Richard Colley, Marquess Wellesley. Photograph Mary Evans Picture Library.

The Hon. Henry Wellesley. Portrait by John Hoppner. Reproduced courtesy of The Duke of Wellington KG; photograph Courtauld Institute of Art.

Caricature of soldiers on the march, by Thomas Rowlandson. Copyright British Museum.

‘Blücher the Brave’: caricature by Thomas Rowlandson. Guildhall Library, Corporation of London. Photograph Bridgeman Art Library, London.

The Duke of Wellington and Marshall Blücher. Photograph Mansell Collection.

Caricature by Isaac Cruikshank. Copyright British Museum.

The Duchess of Wellington, in a drawing by John Hayter. Reproduced courtesy of The Duke of Wellington KG; photograph Courtauld Institute of Art.

Lord Castlereagh. National Portrait Gallery, London. Photograph Mansell Collection.

Harriet Arbuthnot. Photograph Mary Evans Picture Library.

Charles Arbuthnot. Reproduced courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Frances Mary Gascoyne-Cecil, second Marchioness of Salisbury. Portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence. Hatfield House. Reproduced courtesy of Lord Salisbury and National Portrait Gallery, London.

Apsley House, No. i London. Reproduced courtesy of the Board of Trustees of the Wellington Museum, Apsley House.

View of the proposed Waterloo Palace. Reproduced courtesy of the Duke of Wellington KG; photograph Courtauld Institute of Art.

Charles Greville. Photograph Mary Evans Picture Library.

Lady Charlotte Greville. Copyright British Museum.

Oil sketch of the Duke, by Sir Thomas Lawrence. Reproduced courtesy of The Duke of Wellington KG; photograph Courtauld Institute of Art.

‘Achilles in the Sulks’: caricature by Thomas Howell Jones. Copyright British Museum.

Repose, a lithograph by H.B. (John Doyle). Copyright Museum of London.

Punch drawing of the Duke’s statue. Pub. Vol. II, July-December 1846, p. 150. © Punch Ltd.

Walmer Castle. Photograph Mary Evans Picture Library.

‘The Field of Battersea’: caricature by William Heath. Reproduced courtesy of the Board of Trustees of the Wellington Museum, Apsley House.

Sketch by Benjamin Robert Haydon for his Wellington Musing on the Field of Waterloo. Reproduced courtesy of The Duke of Wellington KG; photograph Courtauld Institute of Art.

Wellington Musing on the Field of Waterloo, by Haydon. Reproduced courtesy of the Board of Trustees of the National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside (Walker Art Gallery).

Queen Victoria’s first Privy Council meeting, by Sir David Wilkie. The Royal Collection © Her Majesty The Queen.

Miniature engraving of the Duke aged seventy-five. Reproduced courtesy of The Duke of Wellington KG; photograph Courtauld Institute of Art.

Franz Xaver Winterhalter’s portrait of the Duke with Sir Robert Peel. The Royal Collection © Her Majesty The Queen.

Baroness Burdett-Coutts, by Sir William Charles Ross. Reproduced courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Elizabeth Hay, later Duchess of Wellington, the first Duke’s daughter-in-law. Photograph Mary Evans Picture Library.

Arthur Richard Wellesley, the Duke’s elder son, later second Duke of Wellington. Reproduced courtesy of The Duke of Wellington KG; photograph Courtauld Institute of Art.

Robert Thorburn’s painting of the Duke with his grandchildren. Reproduced courtesy of The Duke of Wellington KG; photograph Courtauld Institute of Art.

COLOUR

Goya’s portrait of Wellington painted in August 1812. The National Gallery London; photograph Bridgeman Art Library, London.

Wellington at Waterloo. Copyright British Museum.

Equestrian portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence. Private Collection; photograph Bridgeman Art Library, London.

Sir David Wilkie’s Chelsea Pensioners reading the Waterloo Despatch. Reproduced courtesy of the Board of Trustees of the Wellington Museum, Apsley House.

Princess Lieven, by Sir Thomas Lawrence. The Hermitage, St Petersburg; photograph Bridgeman Art Library, London.

The Stratfield Saye estate. Reproduced courtesy of The Duke of Wellington KG.

The library at Stratfield Saye. Reproduced courtesy of The Duke of Wellington KG.

The Duke’s bedroom at Apsley House. Reproduced courtesy of the Board of Trustees of the Wellington Museum, Apsley House.

The Duke in 1824, painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence for Sir Robert Peel. Reproduced courtesy of Wellington College.

Franz Xaver Winterhalter’s The First of May. The Royal Collection © Her Majesty The Queen.

‘A Quartette in Character’: caricature by William Heath. Private Collection; photograph Bridgeman Art Library, London.

The Duke at seventy-five: portrait by Charles Robert Leslie. Copyright British Museum.

The Duke’s funeral procession, after a painting by Louis Haghe. Guildhall Library, Corporation of London; photograph Bridgeman Art Library, London.

AUTHOR’S NOTE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Any biographer who now attempts to write a life of the Duke of Wellington does so in the shadow, so to speak, of Elizabeth Longford whose splendid book about him was published in two volumes in 1969 and 1972. This book does not, of course, pretend to take its place; but if, as has been suggested, a person really worth writing about deserves reappraisal every twenty years, the time has certainly come for a new look at the Duke. This one skates rather quickly over his generalship and his political entanglements to concentrate more fully on those aspects of his life suggested by the book’s sub-title.

The idea of my writing it came originally from the Hon. Georgina Stonor, whose knowledge of the Wellington Papers is extensive and whose library of books on the Duke and his family has been placed unreservedly at my disposal. I am extremely grateful to her for all her help, as I am to his Grace the eighth Duke of Wellington for allowing me to consult and quote from his great-great-grandfather’s personal papers at Stratfield Saye and for his assistance when I was there.

I must express my thanks also to Dr C.M. Woolgar, Archivist and Head of Special Collections at the Hartley Institute, the University of Southampton, in whose care are the Duke of Wellington’s official papers, and to Claire Jackson for her help when I was working at the Institute.

Southampton University and Stratfield Saye are the principal repositories of the Duke’s papers; but I have also made use of letters and papers by or about him elsewhere. I have therefore to acknowledge with gratitude the gracious permission of Her Majesty the Queen to make use of material in the Royal Archives, Windsor Castle, and to express my thanks to Lord Raglan for the use of the Raglan Papers, including letters from the Duke to his brother William Wellesley-Pole, at Gwent Record Office; the Marquess of Tweeddale for use of the Yester Papers in the National Library of Scotland; the Marquess of Salisbury for use of papers at Hatfield House including the Westmeath Papers and letters from the Duke to the first wife of the second Marquess of Salisbury, her diary and the Duke’s letters to the second wife of the second Marquess; Mrs M. Fry of Fulbeck Hall for a letter from the Duke to the Countess Dowager of Westmorland in the Fane Papers; Adrian Francis for the ‘Manuscript Account of the Services of John Parker, Corporal 20th Foot’; Wellington College for letters to and from the Duke and his accounts in the college’s archives; and Miss S.M. Fletcher, Archivist, Hampshire Record Office for photocopies of the Duke’s Lieutenancy Papers.

For helping me with these and other papers I am most grateful to Oliver Everett, Librarian, Windsor Castle; David Rimmer of the Gwent Record Office; Mr I.F. Maciver, Assistant Keeper, Manuscripts Division, the National Library of Scotland; Robin Harcourt Williams, Librarian and Archivist to the Marquess of Salisbury; and Bijan Omrani, Deputy Archivist, Wellington College.

I am also much indebted to Dr Norma Aubertin-Potter, Sub-Librarian, All Souls College, Oxford; Simon Bailey of Oxford University Archives, Bodleian Library, Oxford; Richard Olney, Assistant Keeper, the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts; Judith Curthoys, Assistant Archivist, Christ Church, Oxford; Dr J.N. Mills of the Historical Search Room, Scottish Record Office; Penelope Hatfield, College Archivist, Eton College Library; Dr Peter Boyden of the National Army Museum; Dr Linda Washington, Head of the Department of Printed Books, National Army Museum; and the staffs of the British Library, the London Library and the Ravenscroft Library, Henley-on-Thames.

For help in tracing the Duke’s movements and activities when in the provinces I am most grateful to Elizabeth Rees, Chief Archivist, Tyne and Wear Archive Services; Rita Freeman, City Archivist, York; Jennifer Gill, County Record Office, Durham; Eileen Organ, Supervisor, Liverpool Record Office, Central Library, Liverpool; Jeremy McIlwaine, Archivist (Diocesan Records), Hertfordshire County Record Office; Richard Leonard, Research Archivist, Centre for Kentish Studies, Maidstone; Bruce Jackson, County Archivist, Lancashire Record Office; Penny Ward, Heritage Officer, Margate Library; and Janet Adamson, Heritage Officer, Folkestone Library.

For help with portraits and busts and the general inconography of the Duke I have to thank Dr Helen Smailes, National Gallery of Scotland; Dr Philip Ward-Jackson, Deputy Conway Librarian, Courtauld Institute of Art; Ian Ritchie, Archive Assistant, National Portrait Gallery; Paul Goldman, Assistant Keeper, Department of Prints and Drawings, British Museum; Liz Vance, Information Assistant, National Gallery; Fiona Pearson, Research Assistant, Scottish National Gallery of Modem Art; A.W. Potter, Information Assistant, Royal Academy of Arts; Julia Toffolo, Registrar, Government Art Collection; Helen Watson of the Scottish National Gallery; Christopher Eimer; Dr Peter Beal and Stephen Lloyd of Sotheby’s; John Kenworthy-Browne; Jonathan Marsden, Deputy Surveyor of the Queen’s Works of Art; Helen Valentine of the Royal Academy of Arts; Mireille Galinou of the Museum of London; and Marjorie Trusted of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

For their help in a variety of other ways I am most grateful to the Marquess of Anglesey, Lady Marioth Hay, Lady Pamela Barbary, Major D.A.J. Williams, Regimental Secretary of the King’s Royal Hussars, Captain J.G. Fergusson, Richard Way, Diana Cook, Dennis Flower, David Nugent, Peter Crane, Oliver Cooper, Margaret Lewendon, Rosemary Foster, Dr Francis Sheppard, Bruce Hunter of David Higham Associates and Richard Johnson of HarperCollins. I want also to thank Deborah Adams who edited the book; Anna Grapes who helped me choose the illustrations; Hamish Francis who read the proofs; and my wife who made the comprehensive index.

Finally I must say how grateful I am to Professor Norman Gash, biographer of Peel and author of the article on Wellington in the forthcoming New Dictionary of National Biography, for having read the book in typescript and given me much valuable advice for its improvement.

Christopher Hibbert

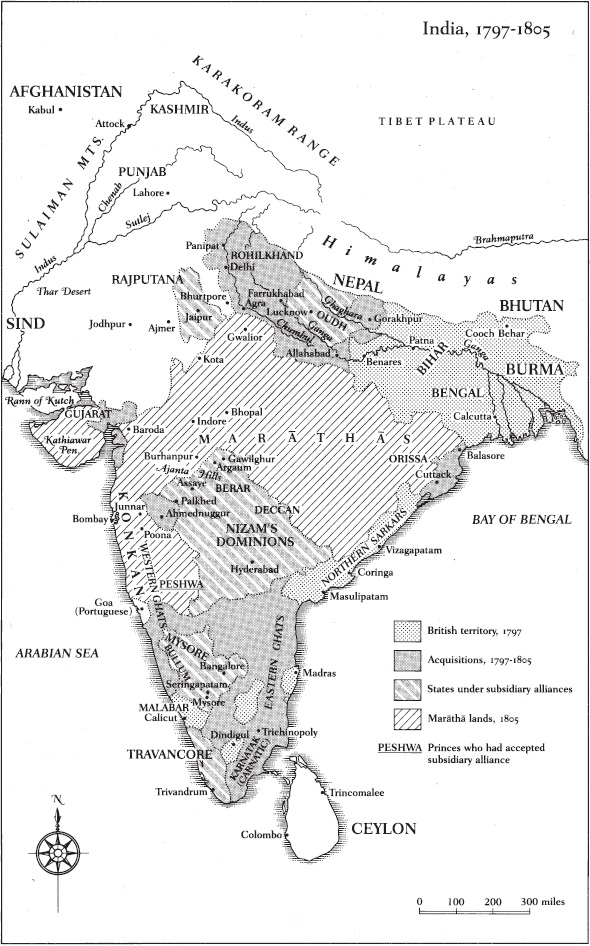

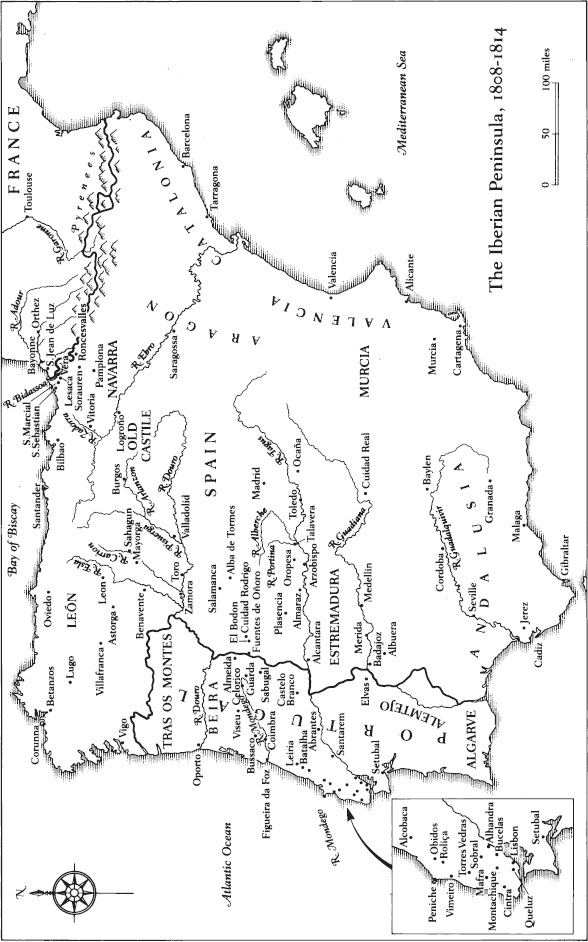

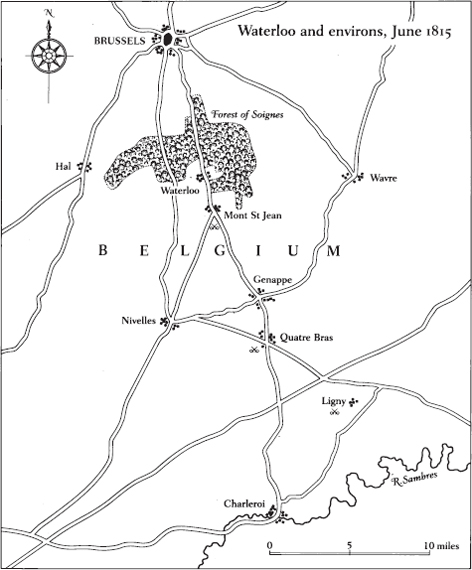

MAPS

I

1769–1815

1 Eton, Dublin and Angers

1769 – 87

‘My ugly boy Arthur is food for powder and nothing more.’

AMONG THE new boys whose baggage was set down at the gates of Eton in the autumn of 1781 were two of the five sons of the first Earl of Mornington. The elder, the Hon. Arthur Wesley, was twelve years old, the younger, Gerald, was nine. Neither had yet shown much aptitude for scholarship and they were not expected to shine at Eton in the glittering manner of their eldest brother, Richard, who had mastered Greek and Latin with equal facility, had, afterwards at Oxford, won the Chancellor’s Prize for Latin Verse, and would, no doubt, have taken an excellent degree had not the early death of his father necessitated his presence at home.

His father, Garret Wesley, Lord Mornington, had not been a practical man. Descendant of an ancient English family which had been settled in Ireland for generations, he had been a member of the Irish House of Commons before passing to the Irish House of Lords. But he had been more interested in music than in politics. His own father, Richard Colley Wesley, had been a musician of sorts, playing the violin quite well, so it was said, ‘for a gentleman’.1 There was an organ in the hall of the Wesleys’ country house, Dangan Castle, in the county of Meath, another organ in the chapel there and a harpsichord in the breakfast room. But Richard Colley Wesley had been essentially an amateur, whereas his son, a composer as well as performer from his early youth, had been able to take his place among the virtuosi of Dublin’s musical world and had been appointed Professor of Music at Trinity College. His godmother, Mary Delany, however, while acknowledging Garret Wesley’s musical talents, found him rather deficient in ‘the punctilios of good breeding’, and had consequently been much gratified when he announced that he was to marry Lady Louisa Augusta Lennox, daughter of the second Duke of Richmond. Unfortunately, Lady Louisa had developed other ideas. Confessing that she had conceived ‘an insurmountable dislike’ for her noble suitor, she had accepted instead the hand of a richer young man; and Lord Mornington, whose father had died the year before, married Anne Hill, the eldest daughter of a banker, Arthur Hill, later Hill-Trevor, the first Viscount Dungan-non, a sixteen-year-old girl who, in the opinion of Mrs Delany, was modest and good-natured but, like her husband, rather gauche in manner,2 and, according to Mrs Nicolson Calvert, the beautiful Irish wife of an English Member of Parliament, a somewhat ‘commonplace character’.3

The young couple had appeared to suit each other well. They had lived contentedly in the country at Dangan Castle and in Dublin in a handsome house facing Sefton Street. Their first child, Richard, had been born in 1760 and was styled Viscount Wellesley, that variation of the family name, which his brothers were later to adopt, being preferred as older and more aristocratic than Wesley with its associations of evangelical Methodism. Other children had followed at regular intervals: a second son, Arthur, who did not live long, a third son, William in 1763, then another boy, Francis, who died in childhood, followed in 1768 by a daughter, Anne, and on 29 April the following year by a sixth child who was named, like his little dead brother, Arthur, after his mother’s father. Arthur’s younger brother, Gerald Valerian, was born in 1770, the youngest son, Henry in 1773, and yet another child, Mary Elizabeth, soon afterwards.

By then the family had left their house in Dublin and moved to London where the children would grow up to speak without the Irish accent which, it was considered, ‘might be a disadvantage’ to them ‘in society hereafter’.4 They lived in rented rooms in Knightsbridge, their father by now in debt, struggling, not very successfully, to maintain a household befitting his rank, as well as a coach, on an income of £1,800 a year. His son, Arthur, who had been given his first lessons in a small school in the shadow of Dangan Castle, was sent to Brown’s Seminary, later known more grandly as Oxford House Academy, in King’s Road, Chelsea. He was, by his own admission, a shy, indolent and dreamy little boy who was often to be seen standing silently alone under a walnut tree while the other children played their rowdy games. So he was not sorry when, his eldest brother having mortgaged the family’s estates in Meath on their father’s death, he was sent with Gerald to Eton.5

Eton in 1781 was a school of some three hundred boys. The activities to be seen on the playing fields appeared to the uninitiated to be more like free-for-all fights than games; and so, indeed, they often were.* It was not until halfway through the next century that football rules became sufficiently standardized for public schools to play matches against each other without brawling on the pitch. An unsociable boy, quarrelsome in his reserve, Arthur Wesley seems to have enjoyed neither football nor cricket; nor is there record of his having played any of the other games with which his fellow Etonians passed the hours they spent outside the classroom, fives and hoops, hopscotch, marbles and battledore. In later years he recalled leaping over a wide ditch in the garden of his old house, but he said he could not remember a fight he had evidently had with an older boy, Robert Percy (‘Bobus’) Smith, the ugly, amusing brother of Sydney Smith, the witty Canon of St Paul’s, whom he had provoked by throwing a stone at him when he was bathing.6 According to the school’s historian, Arthur Wesley did ‘little else’, other than engage in this fight, ‘to attract the attention of his schoolfellows’.7 Certainly he did not look back upon his days at Eton with any pleasure and returned to the school but rarely.†

As for his work in class, he made very slow progress, labouring gloomily in the Fourth Form, his name appearing in the lists at number fifty-four out of a total of seventy-nine boys, many if not most of them younger than himself. His command of the classics, for all the hours he was required to spend poring over Ovid and Caesar, remained so highly uncertain that in later life he was to pronounce that his two standard rules for public speaking were never to take on subjects he knew nothing about and, whenever possible, to avoid quoting Latin.8

Early in 1784, after his younger brother, Henry, had entered the Lower Remove, it was decided that the family’s finances could no longer be stretched to keep Wesley major at a school whose education seemed to be profiting him so little. So he left Eton and, after a short spell with a tutor, a clergyman in Brighton, he was taken by his mother to Brussels where, it was hoped, she might live more economically and he would progress in French more satisfactorily than he had done in Greek and Latin. He did learn to speak French after a fashion and with a Belgian accent; but his other studies were not pursued with noticeable vigour and he spent much of his time in the lodgings his mother had taken for them in the house of a lawyer, Louis Goubert, playing the violin with patient assiduity and some of the skill of his father: a fellow lodger in the house, the son of a Yorkshire baronet, considered that Wesley played very well, adding that it was the only species of talent that the young man appeared to possess.9