Полная версия

Our Land at War: A Portrait of Rural Britain 1939–45

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2015

Copyright © Duff Hart-Davis 2015

Duff Hart-Davis asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

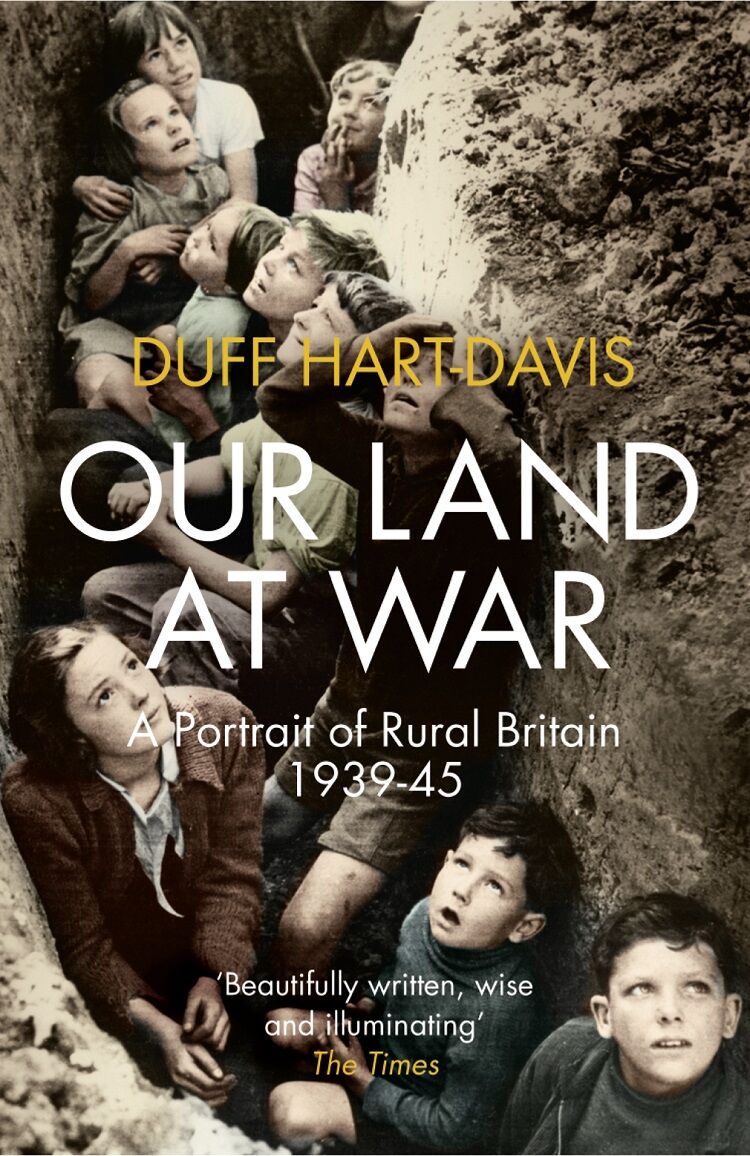

Cover photograph © John Topham/Paul Popper/Popperfoto/Getty Images – Autumn 1940. All eyes on the dog-fight as children in Kent, released from school to help with the hop harvest, take cover in a slit trench.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007516537

Ebook Edition © May 2015 ISBN: 9780007516544

Version: 2016-01-05

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue

1. The Old Ways

2. All Hands to the Plough

3. Exodus

4. Braced for Invasion

5. Going to Ground

6. Adapting to War

7. Rain of Death

8. Food from Everywhere

9. Girls to the Fields

10. In the Woods

11. Laying Up Treasure

12. White Elephants

13. Rescue Operations

14. Plane Fields

15. American Invasion

16. On the Wing

17. Fun and Games

18. Field Sports

19. Animals Under Fire

20. Slate Country

21. Evictions

22. Far North

23. On the Springboard

24. Flying Bombs

25. Unfinished Business

Acknowledgements

Sources

Notes

Picture Section

Index

About the Publisher

Prologue

They shut the road through the woods

Seventy years ago.

Weather and rain have undone it again,

And now you would never know

There was once a road through the woods …

Rudyard Kipling, The Way Through the Woods

I was too young to understand what people meant when they said that war had broken out on 3 September 1939; and as our home was some forty miles west of London, we escaped most of the hazards that harassed rural people closer to the enemy. But I do remember occasional fighter aircraft streaking overhead, searchlight beams flicking about the night sky, and, one afternoon, the rough roar of a V-1 flying bomb – like a malfunctioning motorbike engine – which suddenly cut out above us, leaving the doodlebug to crash and explode a mile away.

I was lucky enough to be brought up in an isolated farmhouse in the Chiltern Hills, and images of rural England at that time remain vivid in my mind. My family were not farmers: we merely rented the house. But we lived deep in the countryside, surrounded by the woods and fields of a large estate, and joined in many of the farm activities. With five bedrooms, the Victorian house was quite large, and perhaps had been built for a farm manager; but its facilities were primitive, and much the same as those in the cottages round about. We had no mains water, and our supply had to be pumped up by hand from one of the brick-lined underground cisterns built around the farm to collect rain for animals and humans. Our electricity – fit only to light feeble bulbs – came from a temperamental generator in one of the sheds.

With my father away in the army, my mother must have had a tough time managing our household. She cooked on an ancient, coal-fired iron range, boiled up the laundry in a copper heated by wood and coal, and wrung out the washing through a mangle before hanging it on a line slung between two old apple trees. She heated her iron on the range, and the only means of keeping the other rooms warm were small open fires. How she did her shopping, I do not know – but as our little Morris Eight was off the road for lack of petrol, I can only assume that she walked the mile to the main road and caught the bus into town, or else that a van from the local grocer made occasional deliveries.

We were seldom short of food, for we had rabbits from the gamekeeper, eggs from our own chickens, vegetables from the garden and any amount of fruit – apples for cooking and eating, currants black and red, blackberries in the autumn and huge white-heart cherries from two splendid trees in the paddock. My mother preserved everything she could lay hands on – eggs in earthenware tubs of slimy waterglass, fruit in Kilner jars with clipped-on lids. In good seasons another venerable tree showered down hundreds of walnuts, and in autumn meadows turned white with mushrooms.

We children had wonderful freedom outdoors. Petrol rationing meant that my sister and I had to make our own way to school, pedalling our bikes along farm lanes or wheeling them through woodland rides to the point on a minor road where a school bus picked us up. Dense laurel thickets and towering beech trees held no terrors, even in the dark of winter afternoons, for the way through the woods was as familiar to us as our garden paths. No sign or building marked our rendezvous on the public highway: the only shelter for our machines was the hollowed-out trunk of a huge beech tree which stood beside the road – and in that fire-blasted cavern we left them, unlocked and unprotected, until the bus brought us back and we recovered them to ride home.

Having been born with a hunter’s instinct, I spent every available minute out of doors. Spring was the time to search for birds’ nests and augment my collection of eggs, which I emptied, in time-honoured fashion, by making a pin-hole at either end and blowing out the contents. I was under strict orders from my parents not to take more than one egg from any nest I found – but the temptation was always strong, and in any case for species deemed harmful, like crows and magpies, the prohibition was waived. Twice I hurt myself quite badly and was carried home with my head covered in blood after falling from a height in attempts to reach the stinking, domed structures built by magpies in the tree-tops. I shall never forget landing face-first in a patch of brambles and ripping my hands to shreds as I crawled desperately through the thorns in an attempt to get breath into my lungs.

Accidents notwithstanding, the nesting season was always a time of miracles. How did a pair of long-tailed tits manage to rear a dozen or fifteen babies inside their tiny, vertical oblong of wool and moss and grass? How did wood pigeons stop their bright-white eggs rolling off their platforms of dry sticks, from which they were constantly departing with a great clatter? How did green woodpeckers interpret the messages they sent each other in the bursts of gunfire – brrrrrp, brrrrrp – which they generated when hammering out nest-holes in the trunks of trees?

Wandering about the woods, I often made for a clearing in which a gnarled and grizzled ancient, with a filthy pork-pie hat crammed down on his head, sat upright on a section of tree trunk, cutting tent pegs from hazel branches. One, two, three jabs against a long blade fixed upright in front of him – and almost before the chips had landed on the ground another peg went onto the pile. He hardly ever spoke; but as he did not seem to resent my presence, I used to stand and watch him, fascinated by the precision and economy of his movements. I see him now, chipping away in a sea of bluebells every spring.

Other choice destinations were the dew ponds scattered about the woods – small, circular pools ten or fifteen yards across, all perfectly round and enclosed by trees or bushes. It was clear from their shape that they had been dug by humans, but there was something mysterious about the way they always contained water. In that high chalk country there were no springs or streams to replenish them, yet they never dried out. Was it rain that filled them, or, as their name suggested, condensing dew? One pool was so thickly covered with algae that we called it the Green Slime – and it was there that I witnessed the magical sight of a woodcock carrying chicks, one at a time, between its thighs. The bird flew low and heavily for about fifty yards, before depositing its freight at a point which it obviously thought safe.

On the farm most of the power came from heavy horses, which did the ploughing and drilling, and hauled the wooden-wheeled harvest wagons into the rickyard behind the barns. They were driven and looked after by old Dave Collis, a small, bent man with one rheumy eye, who was reputed to be deaf only when he wanted to be. The farm also boasted one veteran blue tractor – a sign of things to come; but, like the horses, life moved at a leisurely pace.

The two great events of the year were harvest and threshing. As the corn ripened in July, everybody available joined forces to bring in the barley, wheat and oats: children, office workers, shop girls, boys from school camps organized by the Government – all came out to help. Our harvesting machine was a binder, drawn by two horses – a weird looking contraption with spinning wheels and unguarded drive belts, topped by a skeletal rotating flail which swept the crop backwards onto a reciprocating knife. Round and round the field it crawled, cutting the stalks, ingesting them and binding them into bundles with heavy twine, the knife chattering and the release mechanism giving a loud clack every time it ejected a sheaf.

Great was the excitement as the area of standing corn gradually diminished and rabbits trapped in it began to panic, weaving tell-tale trails of ripples through the ears as they dashed back and forth in search of a safe exit. Boys with sticks and, further out, old farmhands with guns, surrounded the shrinking patch, eager for the quarry to break cover. With the light failing and their shelter almost gone, the rabbits had no option but to run for it – and suddenly all was action: the men firing, the boys yelling, lashing out with our sticks and diving onto individual sheaves as we tried to pin down fugitives which had taken temporary cover. Nobody was squeamish in those days: we knew how to kill a rabbit by chopping it on the back of its neck with the edge of a hand, and how to paunch it by slitting open the skin over its stomach and scooping out the warm entrails with our fingers.

Cutting the corn was only the start of the laborious harvesting operation. The sheaves had to be picked up by hand and stood in pairs to make stooks – three pairs for a wheat or oat stook, four for barley, with a neat tunnel along the middle so that air would flow through and dry the grain in the ears. Boys could make good pocket money from stooking – and we earned it, for wheat sheaves were heavy, and the prickly hairs on barley stalks lacerated the inside of our wrists and forearms, as did the spines of thistles.

Threshing, which took place in winter, was heralded by the arrival of a majestic steam engine, which gave a couple of saucy hoots as it crawled down the last stretch of the lane, crunching gravel under its steel wheels and towing the great drum or barn worker – the threshing machine itself. In the rickyard the two had to be precisely aligned, so that a long canvas belt could transmit power from the flywheel of the traction engine to the drive wheel on the drum. When all was set, work began.

A man, woman or boy on top of the rick pitched sheaves down, one at a time, to a man on the drum, who cut the strings and dropped the loose stalks into the maw of the greasy monster. Standing aloft on the rick, lifting the sheaves with a pitchfork, was exciting work, for every movement might lay bare a nest of mice or rats, which would erupt and make a dash for the edge, launching themselves into space – only to meet their doom among the dogs and boys below. Experienced workers tied twine round the bottoms of their trouser legs to deny mice access, but often a yell or a shriek meant that their defences had been penetrated.

As the sheaves were beaten out in the drum, the air filled with dust, sending hay-fever sufferers into paroxysms of sneezing. Wheat was bad enough, but barley was worse, as the spiky ears set floating in the air left faces red and raw. From a tube on the side of the drum golden corn came pouring out into sacks, and these had to be lifted by hand and carried away for storage. The noise was intoxicating: the steam engine hissing, the drum roaring and rattling, the canvas belt flapping, boys shouting, terriers yapping, whippets and collies barking.

In spite of the war, everything about the farm seemed comfortably old and settled – the eighteenth-century barns, with their huge beams, red-tiled roofs, walls of blackened feather-edge planks and their fusty smell of rats and mice; the carthorses and their stable hung with leather harness; the wooden wagons, some of them gaily painted; the cast-iron hand pumps, mounted on little brick pillars, for bringing up water from the underground cisterns; the hand-turned mangold-cutter; the huge hay knife, three feet long, for chopping slices from the stacks; the heavy platform scales with their 56-lb iron weights. Yet my favourite emblem of perpetuity was not on the farm at all.

Far out in one of the woods was an ancient shepherd’s caravan, with a hooped roof and steps leading up to the door. It stood in a clearing, and although it was still on its wheels in my imagination it had been there for ever: long grass had grown over its axles, and the planks along its walls had weathered to a shade of soft, pale grey furred with lichen. Once a shepherd’s mobile summer home, it was used in my day by the gamekeeper as a store for pheasant food, rabbit traps and so on. But it also had another, more subtle role.

In the middle of one board on its south face was a knot-hole, and anyone peering through it, as though through a pin-hole camera, could see a small area of the opposite wall. At dusk on winter evenings the keeper would light an oil lamp, hang it from the ceiling, and, at the point on which any nocturnal snooper’s eye would fall, prop up a crudely written notice proclaiming in big letters painted on cardboard, BACK IN HALF AN HOUR. Whether or not this enigmatic device had the effect of deterring poachers, none could say; but now, seventy years later, I feel it epitomized the simplicity of country life in those far-off days.

I was not old enough to realize that change was coming apace. Blocks of woodland were being clear-felled, one after another, to help meet the nation’s desperate need of timber – softwood like larch for pit props, hardwood like beech (for which the Chilterns are famous) for building Mosquito fighter-bombers. Another tractor arrived on the farm. Fields that had always been meadows were ploughed for corn, throwing up flints by the million. Long Field, Marlins, Amos – even Shanty Meadow, traditionally sheep ground – down they all went to wheat. Another field was renamed Searchlight, from the installation built there early in the war, and at night slender, incandescent beams blazed from it, raking the sky for intruders. Centuries-old work patterns were being shaken apart by the growing crisis, and gradually life had to change.

One

The Old Ways

Oft did the harvest to their sickle yield,

Their furrow oft the stubborn glebe has broke.

How jocund did they drive their team afield!

How bowed the woods beneath their sturdy stroke!

Thomas Gray, Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard

The First World War had taken thousands of young men from the land. Farmers paid them such miserable wages that they were virtually slaves, so when they saw a chance of escape from drudgery they jumped at it. In Akenfield, his classic evocation of a Suffolk village, Ronald Blythe recorded that in March 1914 one nineteen-year-old, Leonard Thompson, was earning 11s a week, and later told the author: ‘The village people in Suffolk in my day were worked to death. It literally happened. It was not a figure of speech. I was worked mercilessly.’

When the farmer stopped his pay because it was raining and the men couldn’t thresh,

I said to my seventeen-year-old mate, ‘Bugger him. We’ll go off and join the army …’ We walked to Ipswich and got the train to Colchester. We were soaked to the skin but very happy. At the barracks we kissed the Bible and were given a shilling … In my four months’ training with the regiment I put on nearly a stone in weight and got a bit taller. They said it was the food, but it was really because for the first time in my life there had been no strenuous work … We were all delighted when war broke out on August 4th.

Leonard survived the horrors of Gallipoli, the Somme and German prison camp, but thousands of his contemporaries did not. When he returned to Suffolk, for a while things were better on the land. The Corn Production Act of 1917, which guaranteed cereal growers good prices for wheat and oats, enabled farmers to pay higher wages, and hundreds of men joined the Agricultural Labourers’ Union. But then a severe drought in the summer of 1921, and a repeal of the Act in August, precipitated a decline which led to a prolonged agricultural slump.

In 1938 Britain was growing only 30 per cent of its food, and only nine million acres of arable land were under cultivation, compared with eleven million in 1914. The Government saw that if war came the nation’s essential supplies of wheat travelling by ship from North America and Canada would be threatened by Germany’s U-boats. It was imperative that more corn should be grown at home.

Life in the countryside was still largely feudal. Many of the great estates had remained intact, and even if the proprietors no longer flaunted the size of their possessions in their Who’s Who entries (‘Owns 22,000 acres’), they still presided over very substantial areas of the country. Yeoman farmers had their own relatively modest houses and land-holdings, but most farm workers lived in tied cottages – that is, in houses owned by their landlords which went with their jobs. If a man lost his job, he lost his house as well – a system which gave owners an absolute grip of their employees.

By the middle of the 1930s huge areas of the countryside had fallen into a state of dereliction. Landowners had lost heart and let their acres go to ruin; tenant farmers, unable to make a living, had simply given up and gone away, leaving houses to decay or fall down and fields to rot. In the absence of grazing animals or cultivation, thousands of acres had been overrun by weeds, brambles and shrubs. In the high Cotswolds huge tracts had been taken over by thorn bushes and stunted trees. In low-lying areas drain clearance had been abandoned, with the result that hawthorn and bramble had spread so far outwards from the hedges that the undergrowth almost met in the middle of soggy fields.

Farming was decidedly old-fashioned. Mechanization was creeping in, but heavy horses still provided most of the power, outnumbering tractors by thirty to one. At the Centenary Royal Show held in Windsor Great Park early in July 1939 and attended by the King and Queen, the entries included 150 Suffolk Punches, along with 100 Percherons, eighty Shires and fifty Clydesdales.

As Ronald Blythe recorded, the horsemen were always the ‘big men’ on the farm:

They kept in with each other and had secrets. They were a whispering lot. If someone who wasn’t a ploughman came upon them and they happened to be talking, they’d soon change the conversation! The horses were friends and loved like men. Some men would do more for a horse than they would for a wife. The ploughmen talked softly to their teams all day long, and you could see the horses listening.

Since, in 1939, most tasks were still tackled by hand, farm workers needed to be strong, fit and hardy. A ploughman plodded over ten or eleven miles of ground every day, guiding his team, as did a man broadcasting seed or fertilizer by hand. A tractor driver had no protection from sun, wind, rain and snow except for his coat and hat: winter and summer he sat in the open on a steel seat, sprung on a flat steel tongue, and maybe slightly padded with an old hessian sack. He had no cab to shield him from the elements, still less any ear-defenders. His only air conditioning was provided by nature.

Starting one of those old bangers was a labour in itself, especially in winter. Having primed the fuel pump, the driver had to turn the engine over by swinging the crank handle at the front – a procedure that might drag on for ten minutes or more in cold weather. If he failed to keep his thumb on the same side of the handle as his fingers, and the engine kicked back, his thumb could be dislocated or broken. Some farmers had trouble progressing from old equipment to new: one in Cornwall tried to get his new machine to stop by shouting ‘Whoa!’ – and in consequence drove straight through the wall of a shed.

A tractor with rubber tyres was rare. The majority had all-steel rear wheels fitted with angled cleats or protruding lumps called spade-lugs. These gave a grip on fields, but made driving along hard roads impossibly rough – on the surface, the machine and the driver – so whenever a farmer wanted to move his machine any distance along a highway, he had to go through the laborious process of fitting protective metal covers round each wheel, bolting two semi-circular sections together. Rubber tyres were much coveted; they gradually became more available, in effect making a tractor a dual-purpose vehicle, equally at home on field or road; but early in the war any tractor passing along a road attracted attention.

In March 1940 the law was amended to allow boys of twelve and upwards to drive tractors on roads. But boys of eleven or twelve, who had never taken a test, were already working unsupervised on the land. Francis Evans, son of a Gloucestershire farmer, was eleven in 1941 and frequently went ploughing on his own all day. ‘My father would come with me along the road to the field being worked, and then go home on his bicycle, leaving me to carry on.’

At hay-time, in June, everyone turned out to help make the most of good weather: wives and children as well as men. Round the edges of fields, where the grass might be wet and choke a mechanical knife, the hay was still mown with scythes. The mechanical cutter was a reciprocating knife with jagged teeth, powered by gears from the axle, and (in the absence of a tractor) it was pulled by two horses walking slowly.

The cut grass was evenly spread with pitchforks until it had begun to dry in the sun, giving off a delicious smell like that of biscuits cooking; then it was turned and left until it was ready to be collected, either by hand or by a horse-drawn rake with long, curved, downward-facing tines, which could be lifted clear of the ground by pulling a lever. A boy riding jockey on the rake had to pay attention, for if he fell off he might be impaled on the tines before he could stop the horse.