Полная версия

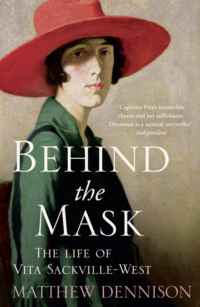

Behind the Mask: The Life of Vita Sackville-West

As long ago as 17 June 1904, Victoria had confided to her diary ‘I hate gossiping’.[28] Later she wrote, ‘People may do what they like but it ought to be either sacred or absolutely private. It is nobody’s business to know our private life. The less said about it, the better …’[29] It was fear of exposure which added a frisson to Edwardian misbehaviour. ‘The code was rigid,’ Vita later wrote in a novel about the period. ‘Within the closed circle of their own set, anybody might do as they pleased, but no scandal must leak out to the uninitiated. Appearances must be respected, though morals might be neglected.’[30]

Swayed by such feelings, and in an attempt to shield her husband and her daughter from scandal, Victoria had written to the Scotts’ counsel on the eve of the trial, ‘Do Spare Them, and attack me as much as you like.’[31] Her plea fell on deaf ears. Her victory involved the very public airing of family secrets she had hoped to conceal; even Lady Connie was called on to give evidence. Among unwelcome revelations were those concerning the Sackville finances, aspersions on Victoria’s own morality and rapacity, and an exposé of Lionel’s relationship with Lady Connie, with all the associated inferences to be drawn about the Sackvilles’ marriage. In Leicester Square, the Alhambra Theatre, home of popular music-hall entertainment, staged a musical revue based on the trial. One of Victoria’s maxims confided to Vita was, ‘One must always tell the truth, darling, if one can, but not all the truth; toute verité n’est pas bonne à dire.’[32] With hindsight, it sounds like closing the stable door when the horse had already bolted. The public display of the Sackvilles’ dirty linen offended every stricture of aristocratic Edwardian conduct: it would mark them for the remainder of their lives. Both Lionel and Victoria paid a high price for the latter’s hard-fought riches. As Vita wrote afterwards, they would realise ‘that innocence was no shield against the pointed fingers of the crowd’.[33]

Yet rich Victoria undoubtedly was. Disregarding Sir John’s unspoken wish that she transfer the contents of the rue Laffitte apartment to Knole, Victoria sold them en bloc to French antiques dealer Jacques Seligmann for £270,000. They were dispersed across the globe, the memory of their rich assembly confined to a short story, Thirty Clocks Strike the Hour, which Vita published in 1932. ‘There were silence and silken walls, and a faint musty smell, and the shining golden floors, and the dimness of mirrors, and the curve of furniture, and the arabesques of the dull gilding on the ivory boiseries.’[34]

Extravagant as she was covetous, Victoria settled down to living off the interest on the sum of £150,000. The capital itself became part of the Sackville Trust, in accordance with the terms of her marriage settlement. Only Vita emerged from the courtroom unscathed. Jurymen and journalists had discovered that Sir John had called her by the pet name ‘Kidlet’. Harmless enough, the label stuck.

In her diary for 7 July, Vita wrote briefly in Italian: ‘Triumphant day! All finished!’[35] She invested the short word ‘all’ with considerable feeling. Her mother’s ‘triumph’ concluded what threatened to be costly legal action with a magnificent windfall. It also brought to an end a troubling five-year period in which the Sackvilles had been continuously involved in, or threatened with, court proceedings.

Three years earlier, in February 1910, Victoria had found herself with Lionel and, briefly, Vita, in London’s High Court. In order to defend her husband’s inheritance of the Sackville estates and title in preference to her brother, Pepita’s son Henry, Victoria was forced publicly to attest her own illegitimacy and that of her siblings. The Daily Mail called the case ‘The Romance of the Sackville Peerage’. It was anything but a romantic interlude for Victoria. Proud and spoilt, she habitually masked deep embarrassment about the circumstances of her birth behind ferocious snobbery. Had it not been for her greedy possessiveness towards Knole, she would have found it a more painful experience. Her mother and father were dead, her husband unfaithful and indifferent to her. In the cold light of the High Court she battled the treachery of her brother Henry and her spiteful, disaffected sisters Amalia and Flora. Only one of Pepita’s surviving children, Victoria’s brother Max, kept clear of the fray. As in the Scott case, Victoria and Lionel won. Knole remained theirs. They retained too the Sackville title, which assured the illegitimate Victoria the respect and deference she craved. In Sevenoaks, their victory was celebrated with a public holiday. They returned to Knole in a carriage drawn by men of the local fire brigade. Bouquets covered the seats. Defeated and deeply in debt, Henry subsequently committed suicide. Expenses associated with the case cost the Sackvilles the enormous sum of £40,000.

In a poem called ‘Heredity’, written in 1928, Vita Sackville-West asked: ‘What is this thing, this strain,/ Persistent, what this shape/ That cuts us from our birth,/ And seals without escape?’ To her cousin Eddy she would write: ‘You and I have got a jolly sort of heredity to fight against.’[36] Dark shadows clouded Vita’s adolescence. On two occasions, crises in the life of her family became public spectacles, she herself – as ‘Kidlet’ – an unwitting heroine of the illustrated papers. Exposed to public gawping were the sexual foibles of her parents and her grandparents, and a world in which love, sex, money and rank coexisted in a greedy system of barter and plunder. Set against this was the feudal loyalty of Sevenoaks locals, the splendour of life in the rue Laffitte, where Seery entertained European royalty, and the majesty and mystery of Knole itself. It was, for Vita, a varied but not a straightforward existence: courtroom exposure of its flaws increased a tendency to regard herself as distinct and apart, which began in her childhood. Ultimately she longed to retreat from view. Inheritance became a vexed issue for Vita, and one that dominated chapters of her life and facets of her mind. Over time she regarded heredity as immutable and inescapable, but unreliable. This in turn coloured her sense of identity: an element of bravado underpinned her stubborn pride. She did not struggle to escape. Her understanding of her inheritance – temperamental, physical, material – shaped the person she became.

PART I

The Edwardians

‘While he was still an infant John learned not to touch glass cases and to be careful with petit-point chairs. His was a lonely but sumptuous childhood, nourished by tales and traditions, with occasional appearances by a beautiful lady dispensing refusals and permissions …’

Violet Trefusis, Broderie Anglaise, 1935

‘IN LIFE,’ WROTE Vita Sackville-West in her best-known novel, The Edwardians, ‘there is only one beginning and only one ending’: birth and death.[37] So let it be in this retelling of Vita’s own life.

Imagine her as a newborn baby, as she herself suggested, ‘lying in a bassinette – having just been deposited for the first time in it … surrounded by grown-ups … whose lives are already complicated’.[38] The bassinette stands temporarily in her mother’s bedroom. The grown-ups are Mrs Patterson the nurse and Vita’s mother and father, Victoria and Lionel Sackville-West. We have already seen something of the complications: more will reveal themselves by stages.

In the early hours of 9 March 1892, the grey and green courtyards of Knole were not, as Vita later described them, ‘quiet as a college’.[39] Howling and shrieking attended her birth. Outside the great Tudor house, once the palace of the Archbishop of Canterbury, once a royal palace and expansive as a village with its six acres of roof, seven courtyards, more than fifty staircases and reputedly a room for every day of the year, darkness hung heavy, ‘deepening the mystery of the park, shrouding the recesses of the garden’;[40] the Virginia creeper that each year crimsoned the walls of the Green Court clung stripped of its glowing leaves. Inside, a night of turmoil dragged towards dawn. Dizzy with her husband’s affection, less than two years into their marriage, Vita’s mother confessed to having ‘drunk deep at the cup of real love till I felt absolutely intoxicated’:[41] not so intoxicated that the experience of childbirth was anything but terrible. Its horrors astonished Victoria Sackville-West. She wept and she yelled. She begged to be killed. She demanded that Lionel administer doses of chloroform. It was all a hundred times worse than this charming egotist had anticipated. Lionel could not open the chloroform bottle; Mrs Patterson was powerless to prevent extensive, extremely painful tearing. And then, within three quarters of an hour of giving birth, she succumbed to ‘intense happiness’. Elation displaced agony. She was dazzled by ‘such a miracle, such an incredible marvel’: ‘one’s own little baby’. She was no stranger to lightning changes of mood.

Her ‘own little baby’ was presented to Victoria Sackville-West by her doting husband. Like a precious stone or a piece of jewellery, Vita lay upon a cushion. Her tiny hands, her miniature yawning, entranced her mother. So, too, her licks and tufts of dark hair. Throughout her pregnancy Victoria had been certain that her unborn child would be a daughter. Long before she was born, Victoria and Lionel had taken to calling her Vita (they could not refer to her as ‘Baby’ since ‘Baby’ was Victoria’s name for Lionel’s penis); her wriggling in the womb had kept Victoria awake at night. On the day of Vita’s birth, Victoria headed her diary entry ‘VITA’: bold capitals indicate that she considered the name settled, inarguable. It was, of course, a contraction of Victoria’s own name, just as the daughter who bore it must expect to become her own small doppelgänger. For good measure Victoria christened her baby Victoria Mary. Mary was a sop to the Catholicism of her youth. It was also a tribute to Mary, Countess of Derby, Lord Sackville’s sister, who had once taken under her wing Pepita’s bastards when first Lord Sackville brought Victoria and her sisters to England. Vita was the only name she would use. Either way, the identities of mother and child were interwoven. Even-tempered and still infatuated, Lionel consented.

And so, at five o’clock in the morning, in her comfortable Green Court bedroom with its many mirrors and elegant four-poster bed reaching right up to the ceiling, Victoria Sackville-West welcomed with open arms the baby she regarded for the moment as a prize chattel. ‘I had the deepest gratitude to Lionel, who I was deeply in love with, for giving me such a gift as that darling baby,’ she remembered many years later.[42] She omitted to mention the lack of mother’s milk which prevented her from feeding Vita: her thoughts were not of her shortcomings but her sufferings. ‘I was not at all comfy,’ she recorded with simple pique. She was ever self-indulgent. The combination of intense love, possessiveness and an assertive sort of self-absorption imprinted itself on Vita’s childhood. In different measure, those same characteristics would re-emerge throughout her life.

In the aftermath of Vita’s birth, Lionel Sackville-West retreated to his study to write letters. He may or may not have been disappointed in the sex of his child, for which Victoria, with a kind of sixth sense, had done her best to prepare him. On 9 March, he conveyed news of his new daughter to no fewer than thirty-eight correspondents. The habit of entrusting intense emotions to the page and ordering those emotions through the written word would similarly form part of Vita’s make-up. As would his daughter, Lionel wrote quickly but with care. Later he shared with her his advice on how to write well.

When Lionel was not writing he read. In the fortnight up to 27 March, he offered his French-educated bride an introduction to the works of Victorian novelist William Makepeace Thackeray. Beginning with The Book of Snobs, he progressed, via Vanity Fair, to The History of Henry Esmond. Appropriately it was Becky Sharpe, self-seeking heroine of Vanity Fair, ‘a wicked woman, a heartless mother and a false wife’, who captured Victoria’s interest. The women shared coquetry, worldliness, allure. In time Victoria would indeed prove herself capable of falsity, heartlessness and something very like wickedness. But it was the story of Henry Esmond that ought to have resonated most powerfully for Lionel and his family.

Victoria’s diary does not suggest that either husband or wife drew parallels between the novel and their own circumstances. Those are for us to identify. As the illegitimate son of an English nobleman, Henry Esmond is unable to inherit the estate of his father, Viscount Castlewood, and ineligible as a suitor for his proud but beautiful cousin Beatrix: the paths to happiness, riches, respectability and title are liberally strewn with thorns. As we have seen, the legal and social ramifications of illegitimacy would for a period dominate the married life of Lionel and Victoria Sackville-West: their affection did not survive the struggle. In turn, Vita’s own life would be shaped, indeed distorted, by her inability as a daughter to inherit her father’s title and estates. In the early hours of 9 March 1892, wind buffeted the beeches of Knole’s park, ‘dying in dim cool cloisters of the woods’ where deer huddled in the darkness;[43] the grey walls of the house, which later reminded Vita of a medieval village, stood impassive. All was not, as Vita wrote glibly in the fictional account of Knole she placed at the centre of The Edwardians, ‘warmth and security, leisure and continuity’:[44] in her own life it seldom would be. There were very real threats to the security of her infant world. In addition, it was ‘continuity’ that demanded the perpetuation of that system of male primogeniture which was to cause her such lasting unhappiness. She once claimed for Knole ‘all the quality of peace and permanence; of mellow age; of stateliness and tradition. It is gentle and venerable.’[45] But that statement was for public consumption. On and off, what Vita expressed publicly and what she felt most strongly failed to overlap. She was born at Knole, but died elsewhere. She would struggle to reconcile that quirk of fate.

In the short term, within days of her birth, baby Vita’s left eye gave cause for concern. Boracic lotion cleared up the problem and Victoria Sackville-West complacently committed to her diary the similarity between the blue of her daughter’s eyes and those of her great-uncle by marriage, Lord Derby. A smoking chimney in Vita’s bedroom resulted in her being moved back into her mother’s room. It was a temporary solution. Victoria’s diary frequently omits any mention of her daughter, even in the first ecstatic days which she celebrated afterwards as more wonderful than anything else in the world. Her thoughts were of herself, of Lionel, of how much she loved him. Most of all she recorded the extent of his love for her. It would be more than a month before she witnessed for the first time Mrs Patterson giving Vita her bath, a sight that nevertheless delighted her. In the meantime she rested, cocooned and apparently safe in her husband’s adoration.

These were happy days, as winter gave way to spring and Vita made her first sorties outdoors. She was accompanied on these excursions by Mrs Patterson, by her father or her grandfather, Lord Sackville. As the little convoy passed, clouds of white pigeons fluttered on to the roof, startled by the opening and closing of doors. ‘You have to look twice before you are sure whether they are pigeons or magnolias,’ Vita remembered.[46] March faded into April and ‘underfoot the blossom was/ Like scattered snow upon the grass’;[47] in the Wilderness, close to Knole’s garden front, daffodils and bluebells carpeted the artful expanse of oak, beech and rhododendron. Sometimes, indoors, Vita was placed on her mother’s bed, with its hangings embroidered with improbably flowering trees, ‘and I watched her for hours, lying or sitting on my lap. Her little sneezes or yawning were so comic. I hugged her till she screamed.’ At other times, husband and wife lay next to one another with their baby between them. When Vita cried, Lionel walked up and down Victoria’s bedroom, cradling her in his arms. In time, when Vita had learnt to talk, ‘she used to look at each of us in turn and nod her head, saying “Dada – Mama –”. This went on for hours and used to delight us.’[48]

These are common enough pictures, albeit the surroundings were uncommonly sumptuous. The air was densely perfumed with a mix of Victoria’s scent (white heliotrope, from a shop off the rue St Honoré in Paris), potted jasmine and gardenias that stood about on every surface, apple logs in the grate and, on window ledges and tables, ‘bowls of lavender and dried rose leaves, … a sort of dusty fragrance sweeter in the under layers’: the famous Knole potpourri, made since the reign of George I to a recipe devised by Lady Betty Germain, a Sackville cousin and former lady-in-waiting to Queen Anne.[49] Such conventional domesticity – husband, wife and baby happy together – is unusual in this chronicle of fragmented emotions. ‘She loved me when I was a baby,’ Vita wrote of her mother in the private autobiography that was published posthumously as Portrait of a Marriage.[50] In her diary, which she kept in French, Victoria described her baby daughter as ‘charmant’, ‘adorable’, ‘si drôle’: ‘toujours de si bonne humour’ (always so good humoured). On 17 June, she and Vita were photographed together by Mr Essenhigh Corke of Sevenoaks. But it was Lionel’s name, ‘Dada’, that Vita uttered first. It was 4 September. She was six months old.

Victoria’s diary charts Vita’s growth and progress. Some of it is standard stuff. There are tantalising glimpses of the future too. On 19 April 1892, Victoria opened a post office savings account for her daughter. Her first deposit of £12 was partly made up of gifts to Vita from Lionel and Lord Sackville. The sum represented the equivalent of nearly a year’s wages for one of Knole’s junior servants, a scullery maid or stable boy. Until her death in 1936, Victoria would continuously play a decisive role in Vita’s finances: her contributions enabled Vita to perpetuate a lifestyle of Edwardian comfort. Later the same year, Victoria introduced her baby daughter to a group of women at Knole. Vita’s reaction surprised her mother. Confronted by new faces, she behaved ‘wildly’ and struggled to get away. It is tempting to witness in her response first flickers of what the adult Vita labelled ‘the family failing of unsociability’.[51] In Vita’s case, that Sackville ‘unsociability’ would amount to virtual reclusiveness.

The faces little Vita loved unhesitatingly belonged to her dolls. Shortly after her first birthday, Victoria made an inventory of her daughter’s dolls. It included those which she herself had bought at bazaars, a French soldier and ‘a Negress’ given to Vita by Victoria’s unmarried sister Amalia, as well as Scottish and Welsh dolls. ‘Vita adores dolls,’ Victoria wrote. In the ‘Given Away’ column of her list of expenses at the end of her diary for 1896, she included ‘Doll for Vita’, for which she paid five shillings. It is the only present Victoria mentions for her four-year-old daughter and contrasts with the many gifts she bestowed on her friends, her expenditure on clothing and the sums she set aside for tipping servants. Happily Vita could not have known of this imbalance. The following year she was photographed on a sturdy wooden seat with three of her dolls, Boysy, Dorothy and ‘Mary of New York’. Wide-eyed, Vita gazes uncertainly at the viewer. She is wearing a froufrou bonnet reminiscent of illustrations in novels by E. Nesbit; her ankles are neatly crossed in black stockings and buttoned pumps. She was two months short of her fifth birthday then and had ceased to ask her mother when she would bring her a little brother;[52] she was still too young to be told of Victoria’s fixed resolve that she would rather drown herself than endure childbirth for a second time. Vita’s dolls had become her playmates and surrogate siblings. She had quickly grown accustomed to being alone: eventually solitude would be her besetting vice. For the moment her favourite doll was tiny and made of wool: Vita called him Clown Archie. He was as unlike ‘Mary of New York’, with her flaxen curls and rosebud mouth, as Vita herself, though there was nothing clown-like about the serious, dark-haired child. There never would be.

By the age of two, Vita was a confident walker. Earlier her grandfather had described to Victoria watching her faltering progress across one of Knole’s courtyards. On that occasion a footman attended the staggering toddler. In the beginning, Vita’s world embraced privilege and pomp. ‘My childhood [was] very much like that of other children,’ she afterwards asserted, itemising memories of children’s games, dressing up and pets.[53] She was mistaken. Granted, there were universal aspects to Vita’s formative years: her love for her dogs and her rabbits; her fear of falling off her pony; her disappointment at the age of five, on witnessing Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee procession from the windows of a grand house in Piccadilly, that the Queen was not wearing her crown; her frustration at her parents’ strictures; even the ugly, homemade Christmas presents she embroidered for Victoria in pink and mauve. Too often her childhood lacked a run-of-the-mill quality. Hers was a distinctive upbringing, even among her peers. Its atypical aspects shaped her as a person and a writer; shaped too her feelings about herself, her family and her sex; shaped her outlook and her sympathies, her moral compass, her emotional requirements.

The trouble lay mostly with her mother. At thirty, recovering at her leisure from her confinement, Victoria Sackville-West remained beguilingly contrary; she had not yet been wholly spoiled. On the one hand she was capricious and snobbish (she described Queen Victoria as looking ‘very common and red-faced’[54]); on the other she was passionate and romantic, still the same eager, loving young woman who had confided to her diary with cosy delight, ‘Every day the same thing, walking … reading, playing the piano, making love’; still capable of enchantment.[55] With her hooded dark eyes and hair that tumbled almost to her knees, she was lovely to look at. In the right mood, she was exhilarating company. Like Juliet Quarles in Vita’s novel The Easter Party, ‘she was irresponsible, unstable, intemperate, and a silly chatterer – but … under all these things she possessed a warm heart’.[56] In time the combination of beauty, wealth and position encouraged less attractive facets to her character, but this illegitimate daughter of a poor Spanish dancer had yet to forget her good fortune in marrying her cousin. Hers was the zeal of a convert, leavened at this stage with apparently boundless joie de vivre: she embraced with gusto the life of an aristocratic chatelaine that had come to her like the happy ending to a fairy tale. As she herself repeated with justification, ‘Quel roman est ma vie!’ (My life is just like a novel). No one ever persuaded her to relinquish the heroine’s role.

Victoria’s year consisted of entertaining at Knole, country house visits and extended Continental holidays; her favourite days were those she spent alone with Lionel. These were leisurely days of flirtation and passionate lovemaking, of arranging and rearranging the many rooms she thrilled to call her own. She papered one room entirely with used postage stamps and made a screen to match. She installed bathrooms, the first for Lord Sackville, one for herself and another for Vita, close to the nursery. Along the garden front of the house, she rearranged furniture in the Colonnade Room to complete its transformation into an elegant if draughty sitting room. Its walls were painted in grisaille with grand architectural trompe l’oeil; seventeenth-century looking glasses and silver sconces threw light on to deep sofas. There Vita’s fifth birthday was celebrated with a Punch and Judy show; Vita dressed on that occasion with appropriate smartness in ‘an embroidered dress with Valenciennes insertion over [a] blue silk slip’, the sort of dress Victoria herself might have worn.[57] As would her daughter, Victoria Sackville-West exulted in her splendid home. ‘Everybody says that I made Knole the most comfortable large house in England, uniting the beauties of Windsor Castle with the comforts of The Ritz, and I never spoilt the real character of Knole,’ she claimed for herself.[58] Knole became her passion and filled her with a pride that was essentially vanity; she delighted in her ‘improvements’ to its vast canvas. ‘No one knew how, when the day was over and the workmen had gone home, she would lay her cheek against the panelling, marked like watered silk, and softer to her than any lips,’ imagined one of her observers.[59] She had no intention of allowing motherhood to unsettle a routine that suited her so admirably. Inevitably, her manner of life affected her daughter.