Полная версия

Slash: The Autobiography

2

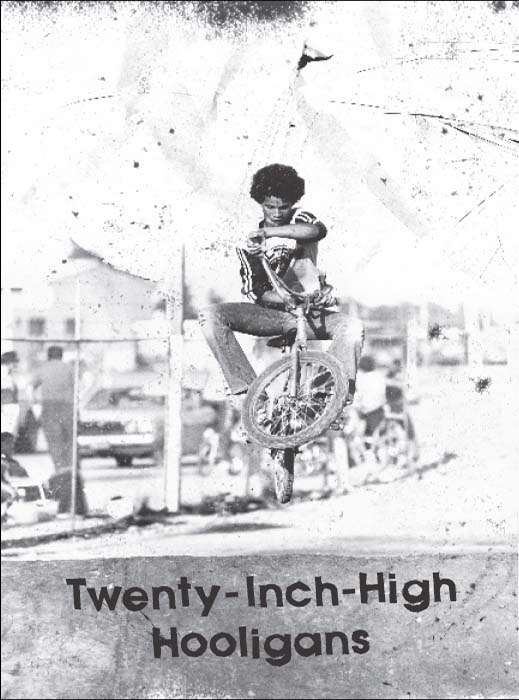

Twenty-Inch-High Hooligans

No one expects the rug to be yanked out from under them; life-changing events usually don’t announce themselves. While instinct and intuition can help provide some warning signs, they can do little to prepare you for the feeling of rootlessness that follows when fate flips your world upside down. Anger, confusion, sadness, and frustration are shaken up together inside you like a snow globe. It takes years for the emotional dust to settle as you do your best just to see through the storm.

My parents’ separation was the picture of an agreeable split. There were no fights or ugly behavior, no lawyers and no courts. Yet it still took me years to come to terms with the hurt. I lost a piece of who I was and had to redefine myself on my own terms. I learned a lot, but those lessons didn’t help me later on when the only other family I’d known disintegrated. I saw the signs that time, when Guns N’ Roses started to come apart at the seams. But even though I did the leaving that time, the same blizzard of feelings lay in wait for me, it was every bit as hard to find my way back to my path again.

When my parents got separated, I was transformed by the sudden change. Inside I was still a good kid, but on the outside I became a problem child. Expressing my emotions is still one of my weaknesses, and what I felt then defied words, so I followed my natural inclinations—I acted out drastically and became a bit of a disciplinary problem at school.

At home, my parents’ promise of a two-abode existence that wouldn’t change a thing hadn’t come to pass. I hardly saw my dad for the first year or so that they were apart, and when I did, it was intense and weird. As I mentioned, the divorce hit him hard and watching him adjust was difficult for me; for a while he couldn’t work at all. He lived meagerly and hung out among his artist friends. When I visited with him, I was along for the ride as he and his friends hung out, drank a lot of red wine, and discussed art and literature, the conversation typically turning to Picasso, my dad’s favorite artist. Dad and I would go on adventures, too, either to the library or the art museum, where we’d sit together and draw.

My mother was home less than ever; she worked constantly, traveling often to support my brother and me. We spent a lot of time with my grandmother Ola Sr., who was always our saving grace when Mom couldn’t make ends meet. We also spent time with my aunt and cousins who lived in greater South Central L.A. Their house was boisterous, filled with the energy of a lot of kids. Our visits there brought some regularity to our idea of family. But all things considered, I had a lot of time on my hands and I took advantage of it.

Once I was twelve, I grew up fast. I had sex, I drank, I smoked cigarettes, I did drugs, I stole, I got kicked out of school, and on a few occasions I would have gone to jail if I hadn’t been underage. I was acting out, making my life as intense and unstable as I felt inside. A trait that has always defined me really came into its own in this period: the intensity with which I pursue my interests. My primary passion, by the time I was twelve, had shifted from drawing to bicycle motocross.

In 1977, BMX racing was the newest extreme sport to follow the surfing and skateboarding craze of the late sixties. It already had a few bona fide stars, such as Stu Thompson and Scott Breithaupt; a few magazines, such as Bicycle Motocross Action and American Freestyler, and more semi-pro and pro competitions were popping up constantly. My grandmother bought me a Webco and I was hooked. I started winning races and was listed in a couple of the magazines as an up-and-coming rider in the thirteen to fourteen age category. I loved it; I was ready to go pro once I’d landed a sponsor, but something was missing. My feelings weren’t clear enough to me to vocalize just what BMX didn’t satisfy inside me. I’d know it when I found it a few years later.

After school, I hung out at bike shops and became part of a team riding for a store called Spokes and Stuff, where I began to collect a bunch of much older friends—some of the other older guys worked at Schwinn in Santa Monica. Ten or so of us would ride around Hollywood every night and all of us but two—they were brothers—came from disturbed or broken domestic situations of some kind. We found solace in one another’s company: our time spent together was the only regular companionship any of us could count on.

We would meet up every afternoon in Hollywood and ride everywhere from Culver City to the La Brea Tar Pits, treating the streets as our bike park. We’d jump off every sloped surface we could find, and whether it was midnight or the middle of rush hour, we always disrespected the pedestrians’ right of way. We were just scrappy kids on twenty-inch-high bikes, but multiplied by ten, in a pack, whizzing down the sidewalk at top speed, we were a force to be reckoned with. We’d jump onto a bus bench, sometimes while some poor stranger was sitting there, we’d hop fire hydrants, and we’d compete constantly to outdo one another. We were disillusioned teenagers trying to navigate difficult times in our lives, and we did so by bunny-hopping all over the sidewalks of L.A.

We’d ride this dirt track out in the Valley, by the youth center in Reseda. It was about fifteen miles away from Hollywood, which is an ambitious goal on a BMX bike. We used to hitch rides on bumpers over Laurel Canyon Boulevard to cut down on our travel time. It’s nothing I’d advise, but we treated passing cars like seats on a ski chairlift: we’d wait on the shoulder, then one by one we’d grab a car and ride it up the hill. Balancing a bike, even one with a low center of gravity, while holding on to a car driving thirty or forty miles an hour is thrilling but tricky on flat ground; attempting it on a series of tight uphill S curves like Laurel Canyon is something else. I’m still not sure how none of us were ever run over. It surprises me more to remember that I did that ride, both up and down hill, without brakes more often than not. In my mind, being the youngest meant that I had something to prove to my friends every time we rode: judging by the looks on their faces after some of my stunts, I succeeded. They might have been only teenagers but my friends weren’t easily impressed.

To tell you the truth, we were a gnarly little gang. One of them was Danny McCracken. He was sixteen; a strong, heavy, silent type, he was already a guy everyone instinctively knew not to fuck with. One night Danny and I stole a bike with bent forks and while he deliberately bunny-hopped it to break the forks and make us all laugh, he fell over the handle-bars and slashed his wrist wide open. I saw it coming and watched it as if in slow-motion as blood started squirting everywhere.

“Ahhh!” Danny shouted. Even in pain, Danny’s voice was oddly soft-spoken considering his size—kind of like Mike Tyson’s.

“Holy shit!”

“Fuck!”

“Danny’s fucked up!”

Danny lived just around the corner, so two of us held our hands over his wrist as blood kept squirting out between our fingers as we walked him home.

We got to his porch and rang the bell. His mom came to the door and we showed her Danny’s wrist. She looked at us unfazed, in disbelief.

“What the fuck do you want me to do about it?” she said, and slammed the door.

We didn’t know what to do; by this time Danny’s face was pale. We didn’t even know where the nearest hospital was. We walked him back down the street, blood still spurting all over us, and flagged down the first car we saw.

I stuck my head in the window. “Hey, my friend is bleeding to death, can you take him to the hospital?” I said hysterically. “He’s gonna die!” Luckily the lady driving was a nurse.

She put Danny in the front seat and we followed her car on our bikes. When he got to the emergency room, Danny didn’t have to wait; blood was pumping out of his wrist like a victim in a horror movie so they admitted him immediately, as the mob of people in the waiting room looked on, pissed. The doctors stitched up his wrist but that wasn’t the end of it: when he was released into the waiting room where we were waiting for him, he somehow popped one of his newly sewn stitches, sending a stream of blood skyward that left a trail across the ceiling, which freaked out and disgusted everyone in range. Needless to say, he was readmitted; his second round of sutures did the trick.

THE ONLY STABLE ONES IN OUR GANG were John and Mike, who we called the Cowabunga Brothers. They were stable for these reasons: they were from the Valley, where the typical American suburban life thrived, their parents were intact, they had sisters, and all of them lived together in a nice quaint house. But they weren’t the only pair of brothers: there were also Jeff and Chris Griffin; Jeff worked at Schwinn and Chris was his younger brother. Jeff was the most adult of our crew; he was eighteen and he had a job that he took seriously. These two weren’t as functional as the Cowabungas, because Chris tried desperately to be like his older brother and failed miserably. Those two had a hot sister named Tracey, who had dyed her hair black in response to the fact that her entire family was naturally blond. Tracey had this whole little Goth style going before Goth was even a scene.

And there was Jonathan Watts, who was the biggest head case among us. He was just insane; he would do anything, regardless of the bodily harm or potential incarceration that might befall him. I was only twelve, but even so, I knew enough about music and people to find it a bit odd that Jonathan and his dad were dedicated Jethro Tull fans. I mean, they worshipped Jethro Tull. I’m sorry to say that Jonathan is no longer with us; he died tragically of an overdose after he’d spent years as both a raging alcoholic and then a flag-waver for Alcoholics Anonymous. I lost touch with him way back, but I saw him again at an AA meeting that I was ordered to attend (we’ll get to all of that in just a little bit), after I was arrested one night in the late eighties. I couldn’t believe it; I walked into this meeting and was listening to all of these people speak and, after a while, realized that the guy leading the meeting, the one who was as gung ho about sobriety as Lieutenant Bill Kilgore, Robert Duval’s character in Apocalypse Now, had been about surfing, was none other than Jonathan Watts. Time is such a powerful catalyst for change; you never know how kindred souls will end up—or where they might see each other again.

Back then, those guys and I spent many an evening at Laurel Elementary School, making very creative use of their playground. It was a hangout for every Hollywood kid with a bike, a skateboard, some booze to drink, or some weed to smoke. The playground had two levels connected by long concrete ramps; it begged to be abused by skaters and bikers. We took full advantage of it by deconstructing the playground’s picnic tables to make them into jumps that linked the two levels. I’m not proud of our chronic destruction of public property, but riding down those two ramps and launching over the fence on my bike was a thrill that was well worth it. As delinquent as it was, it also drew creative types, many kids in Hollywood who went on to do great things hung out there. I remember Mike Balzary, better known as Flea, hanging out, playing his trumpet and graffiti artists putting up murals all the time. It wasn’t the right forum, but everyone there took pride in the scene we created. Unfortunately, the students and teachers of that school were left paying the bill and cleaning up the aftermath every morning.

Slash jumping out at the track on his Cook Bros. bike.

The principal unwisely decided to take matters into his own hands by lying in wait to confront us one night. It didn’t go over well; we kept taunting him, he got too worked up, and my friends and I got into it with him. It got out of hand so quickly that a passerby called the cops. Nothing scatters a pack of kids like the sound of a siren, so most of those present escaped. Unfortunately, I wasn’t one of them. Another kid and I were the only two who were caught; we were handcuffed to the handrail in the front of the school, right on the street, on display for all to see. We were like two hogtied animals, going nowhere and none too happy about it. We refused to cooperate: we cracked wise, we gave them fake names, we did everything short of oinking at them and calling them pigs. They kept asking and did their best to scare us, but we refused to reveal our names and addresses, and since twelve-year-olds don’t carry ID, they were forced to let us go.

PUBERTY KICKED IN FOR ME AROUND thirteen, while I attended Bancroft Junior High in Hollywood. Whatever I was feeling about my family breaking up took a backseat to the intense surging of hormones. Sitting through a whole day of school seemed pointless, so I started to cut. I began smoking pot regularly and riding my bike intensely. I found it hard to control myself; I just wanted to do whatever I wanted to do at a moment’s notice. One night while my friends and I were scheming about how to break into Spokes and Stuff—the same bike store where we hung out—for what reason I can’t remember, I noticed a kid spying on us through the window of an apartment across the alley.

“What are you lookin’ at?” I yelled. “Don’t look at me!” Then I threw a brick through the kid’s window.

His parents called the cops, of course, and the duo that responded to the call chased my friends and me all over town for the rest of the night. We biked for our lives all over Hollywood and West Hollywood; we turned down one-way streets into on-coming traffic, we cut through alleys and through parks. They were as tenacious as Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle, Gene Hackman’s character in The French Connection; every time we turned a corner, they were there. Eventually we fled into the Hollywood Hills and hid in an out-of-the-way canyon like a pack of Wild West outlaws. And just the way it goes down in a cowboy movie, when we thought it was safe to leave the hideout and head back to the ranch, we were headed off at the pass by the same two deputies.

I assume it was because I was the smallest that they decided to chase me when my friends and I split up. I rode hard, all over the neighborhood, unable to shake them, until I finally sought refuge in an underground parking garage. I flew down a few levels, weaving between parked cars, hid in a dark corner, and lay on the ground, hoping they wouldn’t catch me. They had run down there on foot and by the time they got to my level I think they were over it. They vigilantly searched between the cars with their flashlights; about hundred feet away from me they turned back. I got lucky. This battle between my friends and the LAPD continued for the rest of the summer and it certainly wasn’t a constructive use of my time, but in my mind, at that point, that’s what I considered fun.

I was pretty good at keeping my affairs to myself even back then, but when I slipped up, my mother and grandmother were very forgiving. I was home as little as possible by the middle of junior high. In the summer of 1978, I had no idea that my grandmother was moving into a unit in a monstrous new complex that occupied an entire block between Kings Road and Santa Monica Boulevard, although I knew the building well because I’d been riding my bike through it since it was a construction site. My friends and I would get high and race one another through the hallways and down the stairwells, slamming doors in one another’s faces, jumping onto banisters, and leaving creatively shaped skid marks on the freshly painted walls. We were in the midst of doing so when I came screaming around a corner and nearly bowled over my mother and grandmother, who were carrying armloads of Ola Sr.’s belongings into her new apartment. I’ll never forget the look on my grandmother’s face; it was somewhere between shock and horror. I collected myself and shot a look over my shoulder, where I saw the last of my friends take a hard turn out of sight. I had one leg on the ground, one on a pedal, still thinking that I might get away.

“Saul?” Ola Sr. said, in her too-sweet, high-pitched grandmother voice. “Is that you?”

“Yes Grandma,” I said. “It’s me. How are you doing? My friends and I were just coming by to visit.”

That shit didn’t fly at all with my mom, but Ola Sr. was so glad to see me that Ola Jr. let me get away with it. In fact, it all worked out so well in the end that a few weeks later I moved into that very apartment, and that’s when my junior varsity exploits in Hollywood really began to take off. But we’ll get to all of that in just a little bit.

I’M NOT GOING TO OVERANALYZE WHAT became my other new interest—kleptomania—aside from saying that I was a pissed-off early adolescent. I stole what I thought I needed but couldn’t afford. I stole what I thought might make me happy; and sometimes I stole just to steal.

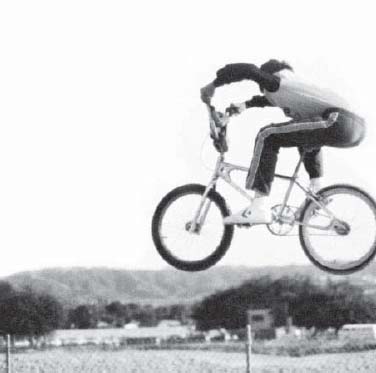

Tearing up the bike track out by the Youth Center in Reseda.

I stole a lot of books, because I’ve always loved to read; I stole a ton of cassettes, because I’ve always loved music. Cassettes, for those too young to have known them, had their disadvantages: the sound quality wore down, they got tangled in tape machines, and they melted in direct sunlight. But they were a breeze to lift. They are like a thinner pack of cigarettes, so an ambitious shoplifter could stuff a bands’ entire catalog in their clothes and walk away unnoticed.

At my worst, I’d steal as much as my clothes could hide, then dump my payload in the bushes and go steal more, sometimes at the same store. One afternoon I stole a few snakes from the Aquarium Stock Company, a pet store that I used to hang out in so much that once they got used to my presence I don’t think they’d ever considered that I’d steal from them. They weren’t complete suckers; I was there out of a true love for the animals they stocked—I just didn’t respect the store enough not to take a few home with me. I’d snatch snakes by wrapping them around my wrists and then putting my jacket on, making sure that they were nestled high enough on my forearm. One day I really went to town and took a load of them, which I stashed somewhere outside while I returned to the store to steal books that would teach me how to care for the rare snakes I’d just stolen.

On another occasion I lifted a Jackson’s chameleon, which isn’t exactly a subtle steal: they are the horned chameleons that measure about ten inches and feed on flies; they are as big as small iguanas and have those strange, protruding, pyramid-like eyes. I had a lot of balls when I was a kid—I just walked right out of the store with it, and it was a very expensive, exotic member of the pet store jungle. As I walked home with the little guy, I couldn’t come up with a story that would adequately explain his presence in my room to my mom. I decided that my only option was to let him live outside, on the vine-covered chain-link fence at the back of our yard, by our garbage cans. I’d stolen a book on Jackson’s chameleons, so I knew that they love to eat flies, and I couldn’t think of a better place for Old Jack to find flies than by the fence behind our garbage cans—because there were plenty to be had. It was an adventure finding him every day because he was so skilled at fading into his environment, as chameleons are known to do. It always took me some time to locate him and I loved the challenge. This arrangement lasted for about five months; after a while, he got better and better at hiding among the vines, until the day I just couldn’t find him at all. I went out there each afternoon for two months, but it was no use. I have no idea what happened to Old Jack, but considering the myriad possibilities that might have befallen him I hope that it ended well.

I’m very lucky not to have been caught for the majority of my shoplifting exploits, because they were pretty extensive. It got this stupid: on a dare, I lifted an inflated rubber raft from a sporting goods store. It took some planning but I pulled it off, and somehow I didn’t get caught.

It’s no big deal; I’ll reveal my “methods,” such as they were: the raft was hung on a wall near the back door of the store, near the hallway that ran right into the back alleyway. Once I managed to get that back door open without arousing suspicion, pulling the raft off the wall was easy. And once the raft was off the wall and on the floor, hidden from general view by some display of camping gear or whatever, I just waited for the right moment to carry it outside and walk it around the corner to where my friends were waiting for me. I didn’t even keep that raft. Once I’d proved that I’d pulled that dare off I dumped it one block away on someone’s front lawn.

I’m not proud of it, but all things considered, when I was ten miles from home with no money and my bike got a flat, I’m glad that it was easy for me to steal an inner tube from Toys “R” Us. Otherwise, I might have been out there hitching home into God only knows what kind of situations. Still, like anyone who repeatedly tempts fate, I must admit that however often you convince yourself that your actions are necessary when you know that they’re not quite right, they will catch up to you in the end.

In my case, in as much as we’re talking about shoplifting, in the end, I got nabbed at Tower Records on Sunset Boulevard, which was my parents’ favorite record shop. I remember that day all too clearly: it was one of those moments when I’d known something was wrong but embarked on the adventure anyway. I was fifteen, I think, and I remember thinking, as I parked my BMX bike outside, that I should be careful in this store in the future. That revelation didn’t help me in the short term: I greedily stuffed cassettes in my jacket, down my pants, and glutted my clothing so much that I thought I should probably buy a few albums just to throw the cashiers off. I believe I walked up to the counter with Cheap Trick’s Dream Police and Led Zeppelin’s Houses of the Holy, and after I was rung up, I was home free in my mind.

I was outside, straddling my bike, ready to jam when a hand clamped down hard on my shoulder. I denied everything but I was busted; they brought me up to the room above the store where they’d been watching me steal through the one-way window and they showed me the footage. They called my mom; I gave up all of the tapes in my pants and they arranged them on a table for her to see when she got there. I got away with a lot as a kid, but getting busted for shoplifting cassettes at the store my parents had frequented for so many years was an offense that meant more within the confines of our family than it did within the letter of the law. I’ll never forget Ola’s expression when she came up to that office above the store and found me sitting there with everything I’d stolen laid out before me. She didn’t say much, and she didn’t have to; it was clear to me that she was over thinking that I could do no wrong.

In the end, Tower didn’t press charges because all of the merchandise was recovered. They let me go on the condition that I would never set foot in their store again, most likely because some manager there recognized that my mom was a well-liked regular.

Of course, when I was hired at the very same store six years later in the video division, during every shift for the first six months, I was convinced that someone was going to remember that I’d been caught stealing and have me fired. I figured that any day now, someone would figure out that I had blatantly lied on my application form and presumed what I knew to be true: that what I did manage to lift until I was caught was worth more than a few months’ paychecks.