Полная версия

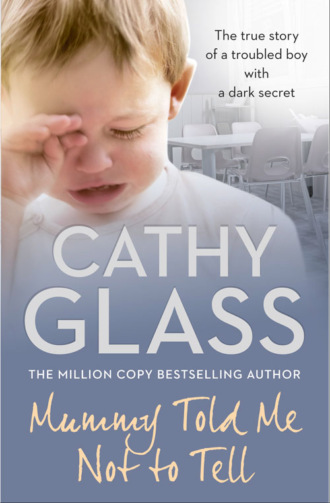

Mummy Told Me Not to Tell: The true story of a troubled boy with a dark secret

Copyright

Certain details in this story, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect the family’s privacy.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperElement 2010

Copyright © Cathy Glass 2007

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015 Cover images © IndexStock/SuperStock (child, posed by model); Shutterstock.com (background)

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Cathy Glass asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007362967

Ebook Edition © September 2008 ISBN: 9780007362974

Version 2016-08-17

Also by Cathy Glass

Damaged

Hidden

Cut

The Saddest Girl in the World

Happy Kids

The Girl in the Mirror

I Miss Mummy

Mummy Told Me Not to Tell

My Dad’s a Policeman (a Quick Reads novel)

Run, Mummy, Run

The Night the Angels Came

Happy Adults

A Baby’s Cry

Happy Mealtimes for Kids

Another Forgotten Child

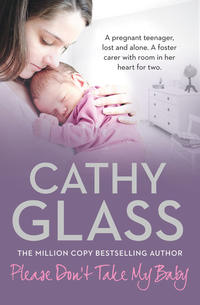

Please Don’t Take My Baby

Will You Love Me?

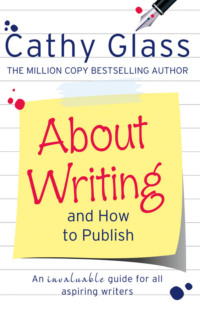

About Writing and How to Publish

Daddy’s Little Princess

The Child Bride

Saving Danny

Girl Alone

The Silent Cry

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Also by Cathy Glass

Prologue

Chapter One: Respite

Chapter Two: A New Record

Chapter Three: Sharky

Chapter Four: Toilet Training

Chapter Five: Safer Caring

Chapter Six: Kids in Care

Chapter Seven: Chaos

Chapter Eight: ‘School’

Chapter Nine: Starting to Get Annoyed

Chapter Ten: Summoned to the Head

Chapter Eleven: An Uncertain Start

Chapter Twelve: The Wider Family Picture

Chapter Thirteen: A ‘Done Bad’ Day

Chapter Fourteen: Seaside Escape

Chapter Fifteen: Set Apart

Chapter Sixteen: Heated Debate

Chapter Seventeen: A Dark Cloud

Chapter Eighteen: Cycle of Abuse

Chapter Nineteen: Normal Family

Chapter Twenty: Forever Family

Chapter Twenty-One: It’s Sad to Say Goodbye

Epilogue

Suggested Topics for Reading-Group Discussion

Sample Chapter

Cathy Glass

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter

About the Publisher

Prologue

‘Is he staying with you now?’ she bellowed. ‘He better be! I ain’t ‘aving ‘im moved again. It’s a bleeding disgrace. Them wankers!’

‘No, he won’t be moved again,’ I reassured Tracey.

Reece was pulling on my arm and making a loud hissing noise. ‘Stand still, good boy,’ I said.

‘Do as you’re bleeding told!’ Tracey yelled, giving him another cuff over the head.

And that was my first meeting with Tracey, Reece’s mother.

Certain details, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect the children in this story

Chapter One Respite

My family and I had said a very emotional farewell to Tayo (the boy whose story I described in my book Hidden), our previous foster child, at the end of October, and because we had grown so close to Tayo it seemed a good idea to do some respite fostering, rather than take on another long-term placement.

‘Respite’ in fostering terms means looking after a foster child (or children) for another carer while that carer takes a much-needed break. Respite fostering doesn’t have the same emotional drain or complications as short or long-term fostering: the child or children arrive clean and well fed, with everything they need for their stay, and safe in the knowledge that they will be returning to their permanent carer(s) after the break. Some foster carers only ever do respite fostering, and have a steady procession of children staying with them. The foster carer looks after the child in exactly the same way as they would any fostered child, but the child’s time with her (or him) is viewed as a short holiday by all concerned, and the foster carer knows that she cannot become too involved. For this reason respite fostering is said to be ‘easier’. While I am always happy to offer respite if I don’t have a foster child, I prefer the involvement of longer placements, and the satisfaction of knowing I have, I hope, in some small way helped a child along the difficult path of life.

After Tayo left and before we embarked on the respite fostering we took a week off and had no foster child at all. This gave me a chance to give the bedroom a thorough cleaning and airing, and also me and my family — Adrian, Paula and Lucy — a chance to come to terms with Tayo’s departure. Although Tayo had left in the best possible circumstances, there was still a sadness, a gap in the family, which would take time to diminish, and would probably only start to go with the arrival of the next child. Some foster carers take a new placement straightaway for this very reason.

The first child to arrive for respite care at the beginning of November was Jemma, a tiny five-year-old who had been with her carers for six months. She stayed with us for a week. Jemma was developmentally delayed and had the needs of a three-year-old. Paula and Lucy, my sixteen- and eighteen-year-old daughters, were very happy to help with this tiny tot and virtually took over from me when they came home from school and college in the evening. But aware that Paula had a lengthy essay to research and write for one of her A-levels, I thought it was just as well Jemma wasn’t staying for longer, as there didn’t appear to be much writing going on in the evening but plenty of playing with Barbie dolls. And while I’m sure Jemma enjoyed her week of non-stop activities with my daughters, she was obviously pleased when her permanent carers returned from their break to take her home.

Three days after Jemma left I was asked to take Daisy for two weeks’ respite care. She was fifteen. I don’t normally foster teenagers — having three of my own is sufficient! And it is thought that a better family balance is achieved if the fostered child (or children) is not of the same age as the child or children already in the family: there is less chance of sibling rivalry, and the foster child’s needs can be better catered for. However, the placement was only for two weeks, and I knew that Daisy was considered a ‘bit of a handful’ and it would therefore be difficult to find respite carers for her. Also, I thought that with Daisy in school and without the high level of needs of a younger child I would have a chance to redecorate the bathroom before I had to start thinking about Christmas.

Daisy was due to arrive at six o’clock with her carer, Kriss, but didn’t arrive until 9.30, having not arrived home until nine o’clock. I could see that Kriss was very stressed as she brought Daisy and her suitcase into the hall and kept apologizing for their lateness. I told Kriss not to worry and reassured her that she hadn’t inconvenienced us (flexibility and adaptability are essential in fostering), and said that I would take good care of Daisy. Daisy was a slim attractive girl with long fair hair, who obviously liked to dress fashionably, and clearly wasn’t happy having to stay with me. I already knew from Jill, my link worker from Homefinders fostering agency, that Kriss was going with a friend for two weeks to Spain. Daisy had been offered the chance to go with them but had refused because she didn’t want to leave her boyfriend behind.

‘Don’t see why I couldn’t have stayed at home,’ Daisy grumbled as Kriss tried to say goodbye.

‘You know why you can’t, love, not at fifteen,’ Kriss said, looking even more stressed. ‘Give me a hug. I must go. My flight leaves in three hours.’ Then, looking at me: ‘God knows what I’d have done if she’d been any later.’

I reassured Kriss again that Daisy would be fine, and I told her to go.

‘Goodbye, love,’ Kriss said to Daisy.

‘Bye,’ Daisy said sullenly, without looking at her and refusing the hug.

‘Bye. Have a really good holiday,’ I called after her. Closing the door, I wondered if Daisy had been very late returning home with the intention of trying to stop Kriss from going.

‘You’re a bit young to stay at home by yourself,’ I said, smiling at Daisy. ‘Anyway we’ve been looking forward to having you stay.’

‘Really,’ Daisy said, looking doubtful, but not as doubtful as I was, for she really did have a face on her.

‘Yes,’ I said brightly. ‘My daughters love having other teenagers’ company.’

Lucy and Paula were in their bedrooms and I called them down and introduced them. With typical teenage embarrassment, on all their parts, the girls smiled sheepishly, eyes down, and just about managed ‘Hi’.

‘I need to wash me hair,’ Daisy said to me.

‘OK, love. Let’s get your case upstairs first.’

I helped Daisy heave her very large suitcase upstairs and into what was to be her bedroom. Then I showed her where the bathroom was and made sure she had everything she needed. Lucy and Paula returned to their rooms with the intention of getting ready for bed — with school and college the following day I liked them to be in bed by ten o’clock.

An hour later, Daisy was still in the bathroom and my initial light taps on the door with ‘Are you OK in there?’ had grown to more insistent knocks, and ‘Daisy, please hurry up! We all need to use the bathroom.’ I thought it was just as well Adrian was at university and not queuing for the bathroom too, because he had begun spending more time in the bathroom than the rest of us put together.

Daisy finally came out of the bathroom at 11.00 and I wasn’t best pleased. Although she was staying with us for only two weeks I needed to set some ground rules, while at the same time making her feel welcome. I made her a bedtime drink — she wanted hot chocolate — and while Lucy and Paula took turns in the bathroom I sat with Daisy on the breakfast stools in the kitchen and gently explained that unlike at Kriss’s, where there were just the two of them, there were four of us in this house, and we all had to use the bathroom. Also, that on a school night I wanted her in bed at 9.30, with the light off at 10.00, as she had to be up and out of the house by 7.30 to catch the bus for school. Daisy liked the hot chocolate — she downed it in one go and asked for another — but didn’t show the same enthusiasm for my bedtime routine.

‘Whatever,’ she said sulkily, as in the teenager’s ‘I hear what you’re saying but I don’t agree.’

‘Excellent,’ I said, sanguine as usual. ‘I know it’s going to be a bit different for you here but I’m sure you will be fine. It’s only two weeks and then you will be back with Kriss.’

‘Yeah, whatever,’ she said again.

I made her another hot chocolate, which she also drank in one go. Then I went with her up to her bedroom and said I wanted her to go straight to sleep and leave the unpacking until morning.

As it turned out, her unpacking was never done. The following morning, I checked she had her bus pass and dinner money, and was dressed in at least some of her school uniform, and then stood on the doorstep and waved her off to school. ‘See you later,’ I called. But I didn’t.

Daisy didn’t return from school. I was worried, but not as worried as I would have been with another child, for I knew from Jill that Daisy had a history of disappearing and usually turned up at her boyfriend’s. However, I still had to follow the usual guidelines for children who didn’t arrive home when they were supposed to and I telephoned the fostering agency at 5.00 p.m. to say Daisy was late. Jill said to give her another hour and then phone again. I phoned at 6.00 to say she still hadn’t returned. By that time Jill had contacted Daisy’s social worker, who said even though Daisy usually turned up at her boyfriend’s I should still report her missing to the police. With Lucy and Paula taking care of dinner, I phoned our local police station and went through the (lengthy) process of completing a ‘missing persons’, all the while feeling I was probably wasting police time. I was.

Five minutes after I’d finished on the phone and had just sat down to dinner, Jill phoned to say Daisy had phoned her social worker and said she was with her boyfriend at his parents’ flat. The social worker had said it was all right for her to stay there. I could hear from Jill’s tone that she didn’t approve, but it wasn’t her decision. I didn’t know enough of Daisy’s situation to know if it was the right decision or not, but I was disappointed Daisy didn’t feel able to stay with us, and regretted the waste of police time.

Daisy popped in after two days to take some clothes from the suitcase that was still unpacked in her bedroom, and accepted a hot chocolate, but she didn’t want to talk. Two days after that she reappeared for another change of clothes and a bath; apparently her boyfriend’s parents’ shower was broken.

‘There is only a week before Kriss comes back,’ I said, catching her en route from the bathroom to what should have been her bedroom. ‘I think it would be really nice if you stayed with us for the week.’

Daisy shrugged, and then asked for the hairdryer and a drink of hot chocolate, which I gave her in the hope it might tempt her to stay. It didn’t, and I guessed Daisy had decided from the outset she wouldn’t be staying with us. She popped in twice the following week for a change of clothes, a bath and, of course, a hot chocolate but didn’t stay long.

I kept daily log notes on Daisy’s comings and goings and phoned Jill with regular updates. I have to keep log notes and regularly update Jill with all the children I foster. Jill kept Daisy’s social worker informed, and she wasn’t unduly concerned for Daisy. Jill and I had to accept that, rightly or wrongly, the social services considered it appropriate for Daisy, aged fifteen, to stay with her boyfriend and his parents. I felt frustrated that I hadn’t been able to do my job properly and look after her.

When Kriss arrived to collect Daisy at the end of the two weeks, she wasn’t surprised to find that Daisy wasn’t with us. Kriss said she would take Daisy’s case and then collect her from her boyfriend’s parents’. Kriss said she’d been fostering Daisy for two years and because Daisy was ‘quite a handful’ she took regular breaks, while making sure Daisy also had holidays. She thanked me for my trouble and apologized for Daisy’s behaviour, which I assured her wasn’t necessary. She added that Daisy often spent the whole weekend at her boyfriend’s parents’, and after numerous meetings and discussions with Daisy’s social worker it had been felt that this was the best arrangement that could be achieved and that at least Daisy had a roof over her head and was safe. The fact that she was sleeping with her boyfriend and presumably having under-age (and illegal) sex had been dealt with by putting Daisy on the pill. Sometimes expectations have to be radically adjusted with teenagers, and a practical working arrangement (with their cooperation) is seen as the better option than trying to impose unrealistic and unworkable goals.

As I helped Kriss load Daisy’s suitcase in the car, feeling that I hadn’t even had the chance to say goodbye to Daisy, who should appear strolling down the street, hand in hand with her boyfriend, but the young lady herself! When she saw Kriss she dropped her boyfriend’s hand and flew into Kriss’s arms, really pleased to see her.

‘Missed you,’ she cried.

‘I missed you too,’ Kriss said.

I smiled and asked Daisy how she was.

‘Good,’ Daisy said.

‘Yeah, good,’ her boyfriend agreed.

Kriss threw me a stoical smile and then opened the rear door of the car for them to get in. I stood on the pavement and saw them off, waving goodbye to the foster child I had never fostered.

After Daisy I had a six-year-old boy, Sam, placed with me for a week. It wasn’t respite but an emergency, as his mother, a single parent with no immediate family, had gone into hospital to give birth to her second child. After Sam left, I redecorated the bathroom and then began Christmas shopping in earnest. I knew I wouldn’t have any more children for respite care this side of Christmas, as everyone would be involved in their own Christmas preparations, not going on holiday, although I could possibly have an emergency placement. I collected Adrian from university and the four of us put up the decorations, and also took the opportunity to go to our local rep theatre one evening for a musical production of Scrooge.

On 22 December, three days before Christmas, Jill phoned and it wasn’t just to wish us a Merry Christmas: ‘Cathy, we’ve had a referral for a seven-year-old boy called Reece,’ she said. ‘He first came into care just over a month ago but hasn’t settled. He’s been with his present carers a week and they have been persuaded to keep him over Christmas as long as there is an end in sight. Will you take him in the New Year?’

Ho ho, I thought, and not the Christmas variety. A week and he’s having to be moved again! ‘Thanks, Jill,’ I said. ‘Merry Christmas to you too.’

She laughed. ‘I’m sure he’s not as bad as they say, just a bit on the lively side. I’ll get back to you with more details and an exact moving date as soon as I have them.’

‘OK. Have a good Christmas.’

‘And you.’

I wasn’t sure I needed more details, for ‘hasn’t settled’ and ‘persuaded to keep him as long as there is an end in sight’ clearly meant that Reece was causing havoc.

Chapter Two A New Record

When Jodie (whose story I wrote about in Damaged) had come to live with me, three years before, she had set something of a record in respect of the number of foster carers she’d gone through — I was her fifth in four months. Children who have been badly emotionally damaged by abuse are either terribly withdrawn or, and more usually, angry, defiant, violent and aggressive, lashing out at everyone and everything around them in a bid to vent their pain on a cruel and confusing world. Not only is this type of behaviour very difficult for the foster carer to deal with, but it is also frightening and upsetting to watch, and emotionally draining for the whole foster family. Foster carers want to do their best for the child they are looking after and hope to see some improvement in the child’s behaviour, as well as keeping everyone in the family safe. Sometimes the situation becomes impossible to manage, if the child’s behaviour is extreme and completely out of control, so the foster carer has to admit they can no longer look after the child. This is called a placement breakdown. While everything is done to avoid such breakdowns, sometimes there is no alternative and the foster child has to be moved to another carer.

On Wednesday 2 January, the first day most people were back at work, Jill phoned shortly after 11.00 a.m. We skipped briefly through the pleasantries of ‘Did you have a nice Christmas and New Year?’ before Jill said: ‘I’m afraid Reece has been very unsettled over Christmas. Are you able to take him tomorrow?’

‘Yes. What time?’

‘I’ll find out. Cathy, apparently he’s been in care six weeks and is on his fourth carer. You’ll be his fifth.’

‘What! That’s ridiculous.’

‘I know, although one carer had him for only two nights, because her mother was taken ill, so it wasn’t Reece’s fault.’

‘No.’ If she really was taken ill, I thought, rather than it being an excuse in a desperate situation. I was starting to feel decidedly uncomfortable and also under pressure. The number of carers a child has been through can often be an indicator of just how ‘challenging’ the child’s behaviour is.

I felt under even more pressure when Jill said: ‘I’ve reassured his social worker you can cope and he won’t be moved from you until everything is sorted out. I’ve got some more details here. I’ll read them out. “He’s seven and a half. His birthday is in August, and he has been on the ‘at risk’ register for three years. He is white Caucasian and has five half-brothers and -sisters, all of whom are in care. There was another sibling but sadly she died as a baby. Reece is of medium build with brown hair and eyes. He eats well and sleeps well, and there are no immediate health concerns, although he does wet the bed and soil himself sometimes.” He came into care on an interim care order. It says here the reasons were: ongoing concerns about the high level of violence within the family home, very poor hygiene in the home, emotional and physical neglect of Reece, the father’s possible sexual assault on his stepdaughter, mum’s assault on Reece and men coming into the house with criminal history, including suspected paedophiles.’ And as if that wasn’t bad enough there was more to come. ‘Oh yes, and he has learning and behavioural difficulties and doesn’t appear to be in school.’ Little wonder he has behavioural difficulties, I thought, having to contend with all that at home.

‘Will mum know where he will be staying?’ I asked.

‘No. Mum is very angry and has a history of assault. The family is well known to social services and has been since the eldest daughter was taken in care eighteen years ago. Oh yes,’ Jill added, ‘and Reece likes to be called Sharky.’

‘Really? That’s a strange nickname.’

‘Perhaps he likes sharks — you know, the way some boys like dinosaurs. I’ve also managed to get some details on why the placements broke down. Would you like to hear them?’

‘Yes, please. Forewarned is forearmed.’

Jill gave a small laugh. ‘The first family were experienced carers, but they had a child of a similar age to Reece and the two didn’t get along. Reece hit the boy with a plastic sword and he needed stitches. The second placement was with a new carer. It was her first placement and she didn’t feel able to cope. I think Reece took his anger out on the furniture, because she’s put in a claim for a new sofa and coffee table. Reece was then moved to another female carer: that was the one whose mother was taken ill. He was then moved to his present carers, a couple called Carol and Tim. They are experienced carers but Carol works part time. With Reece not being in school, it has put a lot of pressure on her and the family.’