Полная версия

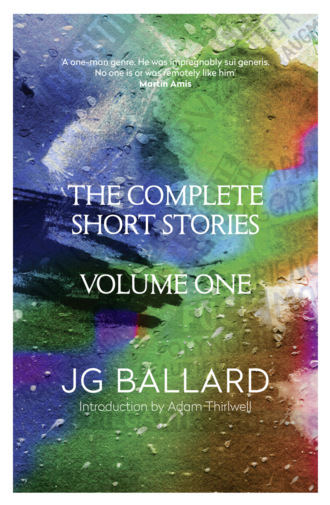

The Complete Short Stories: Volume 1

Franz was watching the house. It was a narrow shabby dwelling sandwiched between a large wholesale furniture store and a new supermarket. An old sign running across the front had been painted over and evidently the ownership had recently changed. The present tenants had made a half-hearted attempt to convert the ground floor room into a cheap stand-up diner. The Fire Police appeared to be doing their best to wreck everything, and pies and smashed crockery were strewn all over the pavement.

The noise died away and everyone waited as the winch began to revolve. The hawsers wound in and tautened, and the front wall of the house staggered outwards in rigid jerky movements.

Suddenly there was a yell from the crowd.

Franz raised his arm. ‘Up there! Look!’

On the fourth floor a man and woman had come to the window and were looking down helplessly. The man lifted the woman on to the ledge and she crawled out and clung to one of the waste pipes. Bottles were lobbed up at them and bounced down among the police. A wide crack split the house from top to bottom and the floor on which the man was standing dropped and catapulted him backwards out of sight. Then one of the lintels in the first floor snapped and the entire house tipped over and collapsed.

Franz and Gregson stood up, almost knocking over the table.

The crowd surged forward through the cordon. When the dust had settled there was nothing left but a heap of masonry and twisted beams. Embedded in this was the battered figure of the man. Almost smothered by the dust he moved slowly, trying to free himself with one hand, and the crowd started roaring again as one of the grabs wound in and dragged him down under the rubble.

The manager of the restaurant pushed past Franz and leant out of the window, his eyes fixed on the dial of a portable detector. Its needle, like all the others, pointed to zero.

A dozen hoses were playing on the remains of the house and after a few minutes the crowd shifted and began to thin out.

The manager switched off the detector and left the window, nodding to Franz. ‘Damn Pyros. You can relax now, boys.’

Franz pointed at the detector. ‘Your dial was dead. There wasn’t a trace of monoxide anywhere here. How do you know they were Pyros?’

‘Don’t worry, we know.’ He smiled obliquely. ‘We don’t want that sort of element in this neighbourhood.’

Franz shrugged and sat down. ‘I suppose that’s one way of getting rid of them.’

The manager eyed Franz. ‘That’s right, boy. This is a good dollar five neighbourhood.’ He smirked to himself. ‘Maybe a dollar six now everybody knows about our safety record.’

‘Careful, Franz,’ Gregson warned him when the manager had gone. ‘He may be right. Pyromaniacs do take over small cafés and food bars.’

Franz stirred his coffee. ‘Dr McGhee estimates that at least fifteen per cent of the City’s population are submerged Pyros. He’s convinced the number’s growing and that eventually the whole City will flame-out.’

He pushed away his coffee. ‘How much money have you got?’

‘On me?’

‘Altogether.’

‘About thirty dollars.’

‘I’ve saved fifteen,’ Franz said. ‘Forty-five dollars; that should be enough for three or four weeks.’

‘Where?’ Gregson asked.

‘On a Supersleeper.’

‘Super –!’ Gregson broke off, alarmed. ‘Three or four weeks! What do you mean?’

‘There’s only one way to find out,’ Franz explained calmly. ‘I can’t just sit here thinking. Somewhere there’s free space and I’ll ride the Sleeper until I find it. Will you lend me your thirty dollars?’

‘But Franz –’

‘If I don’t find anything within a couple of weeks I’ll change tracks and come back.’

‘But the ticket will cost …’ Gregson searched ‘… billions. Forty-five dollars won’t even get you out of the Sector.’

‘That’s just for coffee and sandwiches,’ Franz said. ‘The ticket will be free.’ He looked up from the table. ‘You know …’

Gregson shook his head doubtfully. ‘Can you try that on the Supersleepers?’

‘Why not? If they query it I’ll say I’m going back the long way round. Greg, will you?’

‘I don’t know if I should.’ Gregson played helplessly with his coffee. ‘Franz, how can there be free space? How?’

‘That’s what I’m going to find out,’ Franz said. ‘Think of it as my first physics practical.’

Passenger distances on the transport system were measured point to point by the application of a = √ b2 + c2 + d2. The actual itinerary taken was the passenger’s responsibility, and as long as he remained within the system he could choose any route he liked. Tickets were checked only at the station exits, where necessary surcharges were collected by an inspector. If the passenger was unable to pay the surcharge – ten cents a mile – he was sent back to his original destination.

Franz and Gregson entered the station on 984th Street and went over to the large console where tickets were automatically dispensed. Franz put in a penny and pressed the destination button marked 984. The machine rumbled, coughed out a ticket, and the change slot gave him back his coin.

‘Well, Greg, goodbye,’ Franz said as they moved towards the barrier. ‘I’ll see you in about two weeks. They’re covering me down at the dormitory. Tell Sanger I’m on Fire Duty.’

‘What if you don’t get back, Franz?’ Gregson asked. ‘Suppose they take you off the Sleeper?’

‘How can they? I’ve got my ticket.’

‘And if you do find free space? Will you come back then?’

‘If I can.’

Franz patted Gregson on the shoulder reassuringly, waved and disappeared among the commuters.

He took the local Suburban Green to the district junction in the next county. The Green Line train travelled at an interrupted 70 m.p.h. and the ride took two and a half hours.

At the junction he changed to an express elevator which lifted him out of the sector in ninety minutes, at 400 m.p.h. Another fifty minutes in a Through-Sector Special brought him to the Mainline Terminus which served the Union.

There he bought a coffee and gathered his determination together. Supersleepers ran east and west, halting at this and every tenth station. The next arrived in seventy-two hours time, westbound.

The Mainline Terminus was the largest station Franz had seen, a mile-long cavern thirty levels in depth. Hundreds of elevator shafts sank through the station and the maze of platforms, escalators, restaurants, hotels and theatres seemed like an exaggerated replica of the City itself.

Getting his bearings from one of the information booths, Franz made his way up an escalator to Tier 15, where the Supersleepers berthed. Running the length of the station were two steel vacuum tunnels each three hundred feet in diameter, supported at thirty-four intervals by huge concrete buttresses.

Franz walked along the platform and stopped by the telescopic gangway that plunged into one of the airlocks. Two hundred and seventy degrees true, he thought, gazing up at the curving underbelly of the tunnel. It must come out somewhere. He had forty-five dollars in his pocket, sufficient coffee and sandwich money to last him three weeks, six if he needed it, time anyway to find the City’s end.

He passed the next three days nursing cups of coffee in any of the thirty cafeterias in the station, reading discarded newspapers and sleeping in the local Red trains which ran four-hour journeys round the nearest sector.

When at last the Supersleeper came in he joined the small group of Fire Police and municipal officials waiting by the gangway, and followed them into the train. There were two cars; a sleeper which no one used, and a day coach.

Franz took an inconspicuous corner seat near one of the indicator panels in the day coach, and pulled out his notebook ready to make his first entry.

1st Day: West 270 °. Union 4,350.

‘Coming out for a drink?’ a Fire Captain across the aisle asked. ‘We have a ten-minute break here.’

‘No thanks,’ Franz said. ‘I’ll hold your seat for you.’

Dollar five a cubic foot. Free space, he knew, would bring the price down. There was no need to leave the train or make too many inquiries. All he had to do was borrow a paper and watch the market averages.

2nd Day: West 270 °. Union 7,550.

‘They’re slowly cutting down on these Sleepers,’ someone told him. ‘Everyone sits in the day coach. Look at this one. Seats sixty, and only four people in it. There’s no need to move around. People are staying where they are. In a few years there’ll be nothing left but the suburban services.’

97 cents.

At an average of a dollar a cubic foot, Franz calculated idly, it’s so far worth about $4 × 1027.

‘Going on to the next stop, are you? Well, goodbye, young fellow.’

Few of the passengers stayed on the Sleeper for more than three or four hours. By the end of the second day Franz’s back and neck ached from the constant acceleration. He managed to take a little exercise walking up and down the narrow corridor in the deserted sleeping coach, but had to spend most of his time strapped to his seat as the train began its long braking runs into the next station.

3rd Day: West 270 °. Federation 657.

‘Interesting, but how could you demonstrate it?’

‘It’s just an odd idea of mine,’ Franz said, screwing up the sketch and dropping it in the disposal chute. ‘Hasn’t any real application.’

‘Curious, but it rings a bell somewhere.’

Franz sat up. ‘Do you mean you’ve seen machines like this? In a newspaper or a book?’

‘No, no. In a dream.’

Every half day’s run the pilot signed the log, the crew handed over to their opposites on an Eastbound sleeper, crossed the platform and started back for home.

125 cents.

$8 × 1028.

4th Day: West 270 °. Federation 1,225.

‘Dollar a cubic foot. You in the estate business?’

‘Starting up,’ Franz said easily. ‘I’m hoping to open a new office of my own.’

He played cards, bought coffee and rolls from the dispenser in the washroom, watched the indicator panel and listened to the talk around him.

‘Believe me, a time will come when each union, each sector, almost I might say, each street and avenue will have achieved complete local independence. Equipped with its own power services, aerators, reservoirs, farm laboratories …’

The car bore.

$6 × 1075.

5th Day: West 270 °. 17th Greater Federation.

At a kiosk on the station Franz bought a clip of razor blades and glanced at the brochure put out by the local chamber of commerce.

‘12,000 levels, 98 cents a foot, unique Elm Drive, fire safety records unequalled …’

He went back to the train, shaved, and counted the thirty dollars left. He was now ninety-five million Great-Miles from the suburban station on 984th Street and he knew he could not delay his return much longer. Next time he would save up a couple of thousand.

$7 × 10127.

7th Day: West 270 °. 212th Metropolitan Empire.

Franz peered at the indicator.

‘Aren’t we stopping here?’ he asked a man three seats away. ‘I wanted to find out the market average.’

‘Varies. Anything from fifty cents a –’

‘Fifty!’ Franz shot back, jumping up. ‘When’s the next stop? I’ve got to get off!’

‘Not here, son.’ He put out a restraining hand. ‘This is Night Town. You in real estate?’

Franz nodded, holding himself back. ‘I thought …’

‘Relax.’ He came and sat opposite Franz. ‘It’s just one big slum. Dead areas. In places it goes as low as five cents. There are no services, no power.’

It took them two days to pass through.

‘City Authority are starting to seal it off,’ the man told him. ‘Huge blocks. It’s the only thing they can do. What happens to the people inside I hate to think.’ He chewed on a sandwich. ‘Strange, but there are a lot of these black areas. You don’t hear about them, but they’re growing. Starts in a back street in some ordinary dollar neighbourhood; a bottleneck in the sewage disposal system, not enough ash cans, and before you know it – a million cubic miles have gone back to jungle. They try a relief scheme, pump in a little cyanide, and then – brick it up. Once they do that they’re closed for good.’

Franz nodded, listening to the dull humming air.

‘Eventually there’ll be nothing left but these black areas. The City will be one huge cemetery!’

10th Day: East 90°. 755th Greater Metropolitan –

‘Wait!’ Franz leapt out of his seat and stared at the indicator panel.

‘What’s the matter?’ someone opposite asked.

‘East!’ Franz shouted. He banged the panel sharply with his hand but the lights held. ‘Has this train changed direction?’

‘No, it’s eastbound,’ another of the passengers told him. ‘Are you on the wrong train?’

‘It should be heading west,’ Franz insisted. ‘It has been for the last ten days.’

‘Ten days!’ the man exclaimed. ‘Have you been on this sleeper for ten days?’

Franz went forward and found the car attendant. ‘Which way is this train going? West?’

The attendant shook his head. ‘East, sir. It’s always been going east.’

‘You’re crazy,’ Franz snapped. ‘I want to see the pilot’s log.’

‘I’m afraid that isn’t possible. May I see your ticket, sir?’

‘Listen,’ Franz said weakly, all the accumulated frustration of the last twenty years mounting inside him. ‘I’ve been on this …’

He stopped and went back to his seat.

The five other passengers watched him carefully.

‘Ten days,’ one of them was still repeating in an awed voice.

Two minutes later someone came and asked Franz for his ticket.

‘And of course it was completely in order,’ the police surgeon commented. ‘Strangely enough there’s no regulation to prevent anyone else doing the same thing. I used to go for free rides myself when I was younger, though I never tried anything like your journey.’

He went back to the desk. ‘We’ll drop the charge,’ he said. ‘You’re not a vagrant in any indictable sense, and the transport authorities can do nothing against you. How this curvature was built into the system they can’t explain, it seems to be some inherent feature of the City itself. Now about yourself. Are you going to continue this search?’

‘I want to build a flying machine,’ M. said carefully. ‘There must be free space somewhere. I don’t know … perhaps on the lower levels.’

The surgeon stood up. ‘I’ll see the sergeant and get him to hand you over to one of our psychiatrists. He’ll be able to help you with your dreams!’

The surgeon hesitated before opening the door. ‘Look,’ he began to explain, ‘you can’t get out of time, can you? Subjectively it’s a plastic dimension, but whatever you do to yourself you’ll never be able to stop that clock’ – he pointed to the one on the desk – ‘or make it run backwards. In exactly the same way you can’t get out of the City.’

‘The analogy doesn’t hold,’ M. said. He gestured at the walls around them and the lights in the street outside. ‘All this was built by us. The question nobody can answer is: what was here before we built it?’

‘It’s always been here,’ the surgeon said. ‘Not these particular bricks and girders, but others before them. You accept that time has no beginning and no end. The City is as old as time and continuous with it.’

‘The first bricks were laid by someone,’ M. insisted. ‘There was the Foundation.’

‘A myth. Only the scientists believe in that, and even they don’t try to make too much of it. Most of them privately admit that the Foundation Stone is nothing more than a superstition. We pay it lip service out of convenience, and because it gives us a sense of tradition. Obviously there can’t have been a first brick. If there was, how can you explain who laid it and, even more difficult, where they came from?’

‘There must be free space somewhere,’ M. said doggedly. ‘The City must have bounds.’

‘Why?’ the surgeon asked. ‘It can’t be floating in the middle of nowhere. Or is that what you’re trying to believe?’

M. sank back limply. ‘No.’

The surgeon watched M. silently for a few minutes and paced back to the desk. ‘This peculiar fixation of yours puzzles me. You’re caught between what the psychiatrists call paradoxical faces. I suppose you haven’t misinterpreted something you’ve heard about the Wall?’

M. looked up. ‘Which wall?’

The surgeon nodded to himself. ‘Some advanced opinion maintains that there’s a wall around the City, through which it’s impossible to penetrate. I don’t pretend to understand the theory myself. It’s far too abstract and sophisticated. Anyway I suspect they’ve confused this Wall with the bricked-up black areas you passed through on the Sleeper. I prefer the accepted view that the City stretches out in all directions without limits.’

He went over to the door. ‘Wait here, and I’ll see about getting you a probationary release. Don’t worry, the psychiatrists will straighten everything out for you.’

When the surgeon had left M. stared at the floor, too exhausted to feel relieved. He stood up and stretched himself, walking unsteadily round the room.

Outside the last pilot lights were going out and the patrolman on the catwalk under the roof was using his torch. A police car roared down one of the avenues crossing the street, its rails screaming. Three lights snapped on along the street and then one by one went off again.

M. wondered why Gregson hadn’t come down to the station. Then the calendar on the desk riveted his attention. The date exposed on the fly leaf was 12 August. That was the day he had started off on his journey – exactly three weeks ago.

Today!

Take a westbound Green to 298th Street, cross over at the intersection and get a Red elevator up to Level 237. Walk down to the station on Route 175, change to a 438 suburban and go down to 795th Street. Take a Blue line to the Plaza, get off at 4th and 275th, turn left at the roundabout and –

You’re back where you first started from.

$Hell × 10n.

1957

VENUS SMILES

Low notes on a high afternoon.

As we drove away after the unveiling my secretary said, ‘Mr Hamilton, I suppose you realize what a fool you’ve made of yourself?’

‘Don’t sound so prim,’ I told her. ‘How was I to know Lorraine Drexel would produce something like that?’

‘Five thousand dollars,’ she said reflectively. ‘It’s nothing but a piece of old scrap iron. And the noise! Didn’t you look at her sketches? What’s the Fine Arts Committee for?’

My secretaries have always talked to me like this, and just then I could understand why. I stopped the car under the trees at the end of the square and looked back. The chairs had been cleared away and already a small crowd had gathered around the statue, staring up at it curiously. A couple of tourists were banging one of the struts, and the thin metal skeleton shuddered weakly. Despite this, a monotonous and high-pitched wailing sounded from the statue across the pleasant morning air, grating the teeth of passers-by.

‘Raymond Mayo is having it dismantled this afternoon,’ I said. ‘If it hasn’t already been done for us. I wonder where Miss Drexel is?’

‘Don’t worry, you won’t see her in Vermilion Sands again. I bet she’s halfway to Red Beach by now.’

I patted Carol on the shoulder. ‘Relax. You looked beautiful in your new skirt. The Medicis probably felt like this about Michelangelo. Who are we to judge?’

‘You are,’ she said. ‘You were on the committee, weren’t you?’

‘Darling,’ I explained patiently. ‘Sonic sculpture is the thing. You’re trying to fight a battle the public lost thirty years ago.’

We drove back to my office in a thin silence. Carol was annoyed because she had been forced to sit beside me on the platform when the audience began to heckle my speech at the unveiling, but even so the morning had been disastrous on every count. What might be perfectly acceptable at Expo 75 or the Venice Biennale was all too obviously passé at Vermilion Sands.

When we had decided to commission a sonic sculpture for the square in the centre of Vermilion Sands, Raymond Mayo and I had agreed that we should patronize a local artist. There were dozens of professional sculptors in Vermilion Sands, but only three had deigned to present themselves before the committee. The first two we saw were large, bearded men with enormous fists and impossible schemes – one for a hundred-foot-high vibrating aluminium pylon, and the other for a vast booming family group that involved over fifteen tons of basalt mounted on a megalithic step-pyramid. Each had taken an hour to be argued out of the committee room.

The third was a woman: Lorraine Drexel. This elegant and autocratic creature in a cartwheel hat, with her eyes like black orchids, was a sometime model and intimate of Giacometti and John Cage. Wearing a blue crêpe de Chine dress ornamented with lace serpents and other art nouveau emblems, she sat before us like some fugitive Salome from the world of Aubrey Beardsley. Her immense eyes regarded us with an almost hypnotic calm, as if she had discovered that very moment some unique quality in these two amiable dilettantes of the Fine Arts Committee.

She had lived in Vermilion Sands for only three months, arriving via Berlin, Calcutta and the Chicago New Arts Centre. Most of her sculpture to date had been scored for various Tantric and Hindu hymns, and I remembered her brief affair with a world-famous pop-singer, later killed in a car crash, who had been an enthusiastic devotee of the sitar. At the time, however, we had given no thought to the whining quarter-tones of this infernal instrument, so grating on the Western ear. She had shown us an album of her sculptures, interesting chromium constructions that compared favourably with the run of illustrations in the latest art magazines. Within half an hour we had drawn up a contract.

I saw the statue for the first time that afternoon thirty seconds before I started my speech to the specially selected assembly of Vermilion Sands notables. Why none of us had bothered to look at it beforehand I fail to understand. The title printed on the invitation cards – ‘Sound and Quantum: Generative Synthesis 3’ – had seemed a little odd, and the general shape of the shrouded statue even more suspicious. I was expecting a stylized human figure but the structure under the acoustic drapes had the proportions of a medium-sized radar aerial. However, Lorraine Drexel sat beside me on the stand, her bland eyes surveying the crowd below. A dream-like smile gave her the look of a tamed Mona Lisa.

What we saw after Raymond Mayo pulled the tape I tried not to think about. With its pedestal the statue was twelve feet high. Three spindly metal legs, ornamented with spikes and crosspieces, reached up from the plinth to a triangular apex. Clamped on to this was a jagged structure that at first sight seemed to be an old Buick radiator grille. It had been bent into a rough U five feet across, and the two arms jutted out horizontally, a single row of sonic cores, each about a foot long, poking up like the teeth of an enormous comb. Welded on apparently at random all over the statue were twenty or thirty filigree vanes.

That was all. The whole structure of scratched chromium had a blighted look like a derelict antenna. Startled a little by the first shrill whoops emitted by the statue, I began my speech and was about halfway through when I noticed that Lorraine Drexel had left her seat beside me. People in the audience were beginning to stand up and cover their ears, shouting to Raymond to replace the acoustic drape. A hat sailed through the air over my head and landed neatly on one of the sonic cores. The statue was now giving out an intermittent high-pitched whine, a sitar-like caterwauling that seemed to pull apart the sutures of my skull. Responding to the boos and protests, it suddenly began to whoop erratically, the horn-like sounds confusing the traffic on the far side of the square.