Полная версия

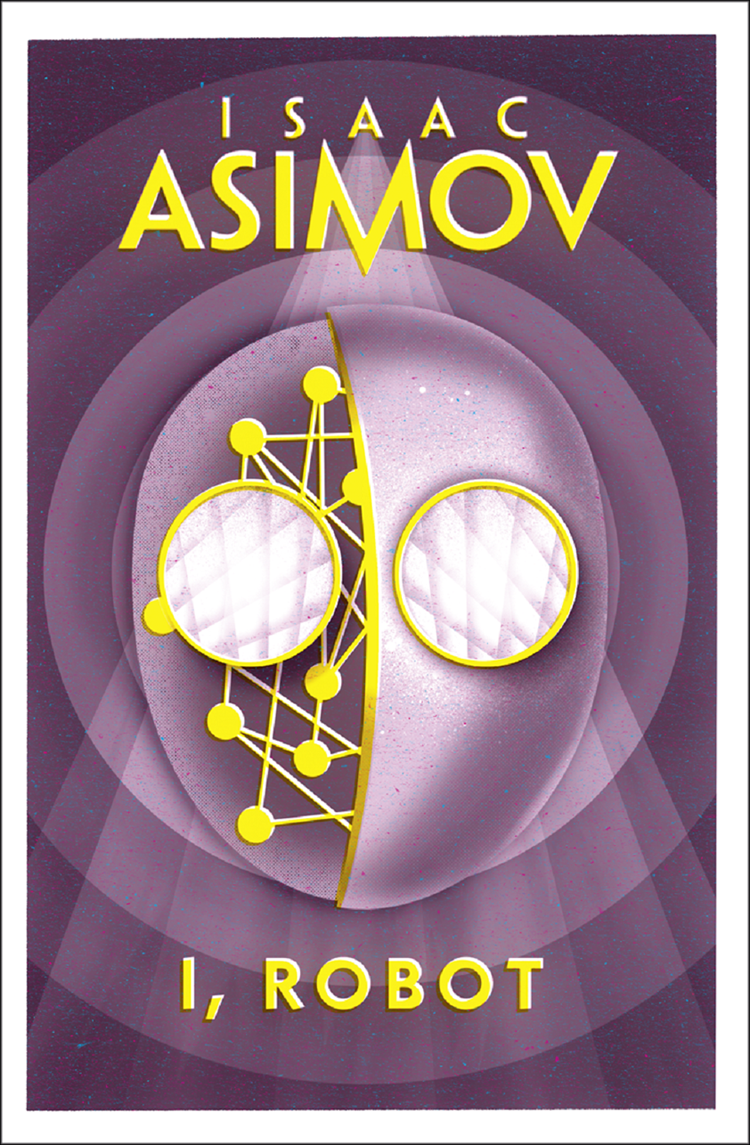

I, Robot

Copyright

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Dobson Books Ltd 1967

Copyright © Isaac Asimov 1950, 1977

Cover design and illustration by Mike Topping © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Isaac Asimov asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008279554

Ebook Edition © March 2018 ISBN: 9780007369355

Version: 2018-04-17

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

1. Robbie

2. Runaround

3. Reason

4. Catch That Rabbit

5. Liar!

6. Little Lost Robot

7. Escape!

8. Evidence

9. The Evitable Conflict

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

The Three Laws of Robotics

1 – A robot may not injure a human being, or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2 – A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3 – A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Handbook of Robotics, 56th Edition, 2058 A.D.

Introduction

I looked at my notes and I didn’t like them. I’d spent three days at US Robots and might as well have spent them at home with the Encyclopedia Tellurica.

Susan Calvin had been born in the year 1982, they said, which made her seventy-five now. Everyone knew that. Appropriately enough, US Robots and Mechanical Men, Inc. was seventy-five also, since it had been in the year of Dr Calvin’s birth that Lawrence Robertson had first taken out incorporation papers for what eventually became the strangest industrial giant in man’s history. Well, everyone knew that, too.

At the age of twenty, Susan Calvin had been part of the particular Psycho-Math seminar at which Dr Alfred Lanning of US Robots had demonstrated the first mobile robot to be equipped with a voice. It was a large, clumsy unbeautiful robot, smelling of machine-oil and destined for the projected mines on Mercury. —But it could speak and make sense.

Susan said nothing at that seminar; took no part in the hectic discussion period that followed. She was a frosty girl, plain and colorless, who protected herself against a world she disliked by a mask-like expression and hypertrophy of intellect. But as she watched and listened, she felt the stirrings of a cold enthusiasm.

She obtained her bachelor’s degree at Columbia in 2003 and began graduate work in cybernetics.

All that had been done in the mid-twentieth century on ‘calculating machines’ had been upset by Robertson and his positronic brain-paths. The miles of relays and photocells had given way to the spongy globe of plantinumiridium about the size of a human brain.

She learned to calculate the parameters necessary to fix the possible variables within the ‘positronic brain’, to construct ‘brains’ on paper such that the responses to given stimuli could be accurately predicted.

In 2008, she obtained her Ph.D. and joined United States Robots as a ‘Robopsychologist’, becoming the first great practitioner of a new science. Lawrence Robertson was still president of the corporation; Alfred Lanning had become director of research.

For fifty years, she watched the direction of human progress change – and leap ahead.

Now she was retiring – as much as she ever could. At least, she was allowing someone else’s name to be inset upon the door of her old office.

That, essentially, was what I had. I had a long list of her published papers, of the patents in her name; I had the chronological details of her promotions— In short I had her professional ‘vita’ in full detail.

But that wasn’t what I wanted.

I needed more than that for my feature articles for Interplanetary Press. Much more.

I told her so.

‘Dr Calvin,’ I said, as lushly as possible, ‘in the mind of the public you and US Robots are identical. Your retirement will end an era and—’

‘You want the human-interest angle?’ She didn’t smile at me. I don’t think she ever smiles. But her eyes were sharp, though not angry. I felt her glance slide through me and out my occiput and I knew that I was uncommonly transparent to her; that everybody was.

But I said, ‘That’s right.’

‘Human interest out of Robots? A contradiction.’

‘No, doctor. Out of you.’

‘Well, I’ve been called a robot myself. Surely, they’ve told you I’m not human.’

They had, but there was no point in saying so.

She got up from her chair. She wasn’t tall and she looked frail. I followed her to the window and we looked out.

The offices and factories of US Robots were a small city; spaced and planned. It was flattened out like an aerial photograph.

‘When I first came here,’ she said, ‘I had a little room in a building right about there where the fire-house is now.’ She pointed. ‘It was torn down before you were born. I shared the room with three others. I had half a desk. We built our robots all in one building. Output – three a week. Now look at us.’

‘Fifty years,’ I hackneyed, ‘is a long time.’

‘Not when you’re looking back at them,’ she said. ‘You wonder how they vanished so quickly.’

She went back to her desk and sat down. She didn’t need expression on her face to look sad, somehow.

‘How old are you?’ she wanted to know.

‘Thirty-two,’ I said.

‘Then you don’t remember a world without robots. There was a time when humanity faced the universe alone and without a friend. Now he has creatures to help him; stronger creatures than himself, more faithful, more useful, and absolutely devoted to him. Mankind is no longer alone. Have you ever thought of it that way?’

‘I’m afraid I haven’t. May I quote you?’

‘You may. To you, a robot is a robot. Gears and metal, electricity and positrons. —Mind and iron! Human-made! If necessary, human-destroyed! But you haven’t worked with them, so you don’t know them. They’re a cleaner, better breed than we are.’

I tried to nudge her gently with words, ‘We’d like to hear some of the things you could tell us; get your views on robots. The Interplanetary Press reaches the entire Solar System. Potential audience is three billion, Dr Calvin. They ought to know what you could tell them on robots.’

It wasn’t necessary to nudge. She didn’t hear me, but she was moving in the right direction.

‘They might have known from the start. We sold robots for Earth-use then – before my time it was, even. Of course, that was when robots could not talk. Afterward, they became more human and opposition began. The labor unions, of course, naturally opposed robot competition for human jobs, and various segments of religious opinion had their superstitious objections. It was all quite ridiculous and quite useless. And yet there it was.’

I was taking it down verbatim on my pocket-recorder, trying not to show the knuckle-motions of my hand. If you practice a bit, you can get to the point where you can record accurately without taking the little gadget out of your pocket.

‘Take the case of Robbie,’ she said. ‘I never knew him. He was dismantled the year before I joined the company – hopelessly out-of-date. But I saw the little girl in the museum—’

She stopped, but I didn’t say anything. I let her eyes mist up and her mind travel back. She had lots of time to cover.

‘I heard about it later, and when they called us blasphemers and demon-creators, I always thought of him. Robbie was a non-vocal robot. He couldn’t speak. He was made and sold in 1996. Those were the days before extreme specialization, so he was sold as a nursemaid—’

‘As a what?’

‘As a nursemaid—’

1

Robbie

‘Ninety-eight – ninety-nine – one hundred.’ Gloria withdrew her chubby little forearm from before her eyes and stood for a moment, wrinkling her nose and blinking in the sunlight. Then, trying to watch in all directions at once, she withdrew a few cautious steps from the tree against which she had been leaning.

She craned her neck to investigate the possibilities of a clump of bushes to the right and then withdrew farther to obtain a better angle for viewing its dark recesses. The quiet was profound except for the incessant buzzing of insects and the occasional chirrup of some hardy bird, braving the midday sun.

Gloria pouted, ‘I bet he went inside the house, and I’ve told him a million times that that’s not fair.’

With tiny lips pressed together tightly and a severe frown crinkling her forehead, she moved determinedly toward the two-story building up past the driveway.

Too late she heard the rustling sound behind her, followed by the distinctive and rhythmic clump-clump of Robbie’s metal feet. She whirled about to see her triumphing companion emerge from hiding and make for the home-tree at full speed.

Gloria shrieked in dismay. ‘Wait, Robbie! That wasn’t fair, Robbie! You promised you wouldn’t run until I found you.’ Her little feet could make no headway at all against Robbie’s giant strides. Then, within ten feet of the goal, Robbie’s pace slowed suddenly to the merest of crawls, and Gloria, with one final burst of wild speed, dashed pantingly past him to touch the welcome bark of home-tree first.

Gleefully, she turned on the faithful Robbie, and with the basest of ingratitude, rewarded him for his sacrifice by taunting him cruelly for a lack of running ability.

‘Robbie can’t run!’ she shouted at the top of her eight-year-old voice. ‘I can beat him any day. I can beat him any day.’ She chanted the words in a shrill rhythm.

Robbie didn’t answer, of course – not in words. He pantomimed running, instead, inching away until Gloria found herself running after him as he dodged her narrowly, forcing her to veer in helpless circles, little arms outstretched and fanning at the air.

‘Robbie,’ she squealed, ‘stand still!’ —And the laughter was forced out of her in breathless jerks.

—Until he turned suddenly and caught her up, whirling her round, so that for her the world fell away for a moment with a blue emptiness beneath, and green trees stretching hungrily downward towards the void. Then she was down in the grass again, leaning against Robbie’s leg and still holding a hard, metal finger.

After a while, her breath returned. She pushed uselessly at her disheveled hair in vague imitation of one of her mother’s gestures and twisted to see if her dress were torn.

She slapped her hand against Robbie’s torso, ‘Bad boy! I’ll spank you!’

And Robbie cowered, holding his hands over his face so that she had to add, ‘No, I won’t, Robbie. I won’t spank you. But anyway, it’s my turn to hide now because you’ve got longer legs and you promised not to run till I found you.’

Robbie nodded his head – a small parallelepiped with rounded edges and corners attached to a similar but much larger parallelepiped that served as torso by means of a short, flexible stalk – and obediently faced the tree. A thin, metal film descended over his glowing eyes and from within his body came a steady, resonant ticking.

‘Don’t peek now – and don’t skip any numbers,’ warned Gloria, and scurried for cover.

With unvarying regularity, seconds were ticked off, and at the hundredth, up went the eyelids, and the glowing red of Robbie’s eyes swept the prospect. They rested for a moment on a bit of colorful gingham that protruded from behind a boulder. He advanced a few steps and convinced himself that it was Gloria who squatted behind it.

Slowly, remaining always between Gloria and home-tree, he advanced on the hiding place, and when Gloria was plainly in sight and could no longer even theorize to herself that she was not seen, he extended one arm toward her, slapping the other against his leg so that it rang again. Gloria emerged sulkily.

‘You peeked!’ she exclaimed, with gross unfairness. ‘Besides I’m tired of playing hide-and-seek. I want a ride.’

But Robbie was hurt at the unjust accusation, so he seated himself carefully and shook his head ponderously from side to side.

Gloria changed her tone to one of gentle coaxing immediately, ‘Come on, Robbie. I didn’t mean it about the peeking. Give me a ride.’

Robbie was not to be won over so easily, though. He gazed stubbornly at the sky, and shook his head even more emphatically.

‘Please, Robbie, please give me a ride.’ She encircled his neck with rosy arms and hugged tightly. Then, changing moods in a moment, she moved away. ‘If you don’t, I’m going to cry,’ and her face twisted appallingly in preparation.

Hard-hearted Robbie paid scant attention to this dreadful possibility, and shook his head a third time. Gloria found it necessary to play her trump card.

‘If you don’t,’ she exclaimed warmly, ‘I won’t tell you any more stories, that’s all. Not one—’

Robbie gave in immediately and unconditionally before this ultimatum, nodding his head vigorously until the metal of his neck hummed. Carefully, he raised the little girl and place her on his broad, flat shoulders.

Gloria’s threatened tears vanished immediately and she crowed with delight. Robbie’s metal skin, kept at a constant temperature of seventy by the high resistance coils within, felt nice and comfortable, while the beautifully loud sound her heels made as they bumped rhythmically against his chest was enchanting.

‘You’re an air-coaster, Robbie, you’re a big, silver air-coaster. Hold out your arms straight. —You got to, Robbie, if you’re going to be an air-coaster.’

The logic was irrefutable. Robbie’s arms were wings catching the air currents and he was a silver ’coaster.

Gloria twisted the robot’s head and leaned to the right. He banked sharply. Gloria equipped the ’coaster with a motor that went ‘Br-r-r’ and then with weapons that went ‘Powie’ and ‘Sh-sh-shshsh.’ Pirates were giving chase and the ship’s blasters were coming into play. The pirates dropped in a steady rain.

‘Got another one. —Two more!’ she cried.

Then ‘Faster, men,’ Gloria said pompously, ‘we’re running out of ammunition.’ She aimed over her shoulder with undaunted courage and Robbie was a blunt-nosed spaceship zooming through the void at maximum acceleration.

Clear across the field he sped, to the patch of tall grass on the other side, where he stopped with a suddenness that evoked a shriek from his flushed rider, and then tumbled her on to the soft, green carpet.

Gloria gasped and panted, and gave voice to intermittent whispered exclamations of ‘That was nice!’

Robbie waited until she had caught her breath and then pulled gently at a lock of hair.

‘You want something?’ said Gloria, eyes wide in an apparently artless complexity that fooled her huge ‘nursemaid’ not at all. He pulled the curl harder.

‘Oh, I know. You want a story.’

Robbie nodded rapidly.

‘Which one?’

Robbie made a semi-circle in the air with one finger.

The little girl protested, ‘Again? I’ve told you Cinderella a million times. Aren’t you tired of it? —It’s for babies.’

Another semi-circle.

‘Oh, hell,’ Gloria composed herself, ran over the details of the tale in her mind (together with her own elaborations, of which she had several) and began:

‘Are you ready? Well – once upon a time there was a beautiful little girl whose name was Ella. And she had a terribly cruel step-mother and two very ugly and very cruel step-sisters and—’

Gloria was reaching the very climax of the tale – midnight was striking and everything was changing back to the shabby originals lickety-split, while Robbie listened tensely with burning eyes – when the interruption came.

‘Gloria!’

It was the high-pitched sound of a woman who has been calling not once, but several times; and had the nervous tone of one in whom anxiety was beginning to overcome impatience.

‘Mamma’s calling me,’ said Gloria, not quite happily. ‘You’d better carry me back to the house, Robbie.’

Robbie obeyed with alacrity for somehow there was that in him which judged it best to obey Mrs Weston, without as much as a scrap of hesitation. Gloria’s father was rarely home in the daytime except on Sunday – today, for instance – and when he was, he proved a genial and understanding person. Gloria’s mother, however, was a source of uneasiness to Robbie and there was always the impulse to sneak away from her sight.

Mrs Weston caught sight of them the minute they rose above the masking tufts of long grass and retired inside the house to wait.

‘I’ve shouted myself hoarse, Gloria,’ she said, severely. ‘Where were you?’

‘I was with Robbie,’ quavered Gloria. ‘I was telling him Cinderella, and I forgot it was dinner-time.’

‘Well, it’s a pity Robbie forgot, too.’ Then, as if that reminded her of the robot’s presence, she whirled upon him. ‘You may go, Robbie. She doesn’t need you now.’ Then, brutally, ‘And don’t come back till I call you.’

Robbie turned to go, but hesitated as Gloria cried out in his defense, ‘Wait, Mamma, you got to let him stay. I didn’t finish Cinderella for him. I said I would tell him Cinderella and I’m not finished.’

‘Gloria!’

‘Honest and truly, Mamma, he’ll stay so quiet, you won’t even know he’s here. He can sit on the chair in the corner, and he won’t say a word – I mean he won’t do anything. Will you, Robbie?’

Robbie, appealed to, nodded his massive head up and down once.

‘Gloria, if you don’t stop this at once, you shan’t see Robbie for a whole week.’

The girl’s eyes fell, ‘All right! But Cinderella is his favorite story and I didn’t finish it. —And he likes it so much.’

The robot left with a disconsolate step and Gloria choked back a sob.

George Weston was comfortable. It was a habit of his to be comfortable on Sunday afternoons. A good, hearty dinner below the hatches; a nice, soft, dilapidated couch on which to sprawl; a copy of the Times; slippered feet and shirtless chest – how could anyone help but be comfortable?

He wasn’t pleased, therefore, when his wife walked in. After ten years of married life, he still was so unutterably foolish as to love her, and there was no question that he was always glad to see her – still Sunday afternoons just after dinner were sacred to him and his idea of solid comfort was to be left in utter solitude for two or three hours. Consequently, he fixed his eye firmly upon the latest reports of the Lefebre–Yoshida expedition to Mars (this one was to take off from Lunar Base and might actually succeed) and pretended she wasn’t there.

Mrs Weston waited patiently for two minutes, then impatiently for two more, and finally broke the silence.

‘George!’

‘Hmpph?’

‘George, I say! Will you put down that paper and look at me?’

The paper rustled to the floor and Weston turned a weary face toward his wife, ‘What is it, dear?’

‘You know what it is, George. It’s Gloria and that terrible machine.’

‘What terrible machine?’

‘Now don’t pretend you don’t know what I’m talking about. It’s that robot Gloria calls Robbie. He doesn’t leave her for a moment.’

‘Well, why should he? He’s not supposed to. And he certainly isn’t a terrible machine. He’s the best darn robot money can buy and I’m damned sure he set me back half a year’s income. He’s worth it, though – darn sight cleverer than half my office staff.’

He made a move to pick up the paper again, but his wife was quicker and snatched it away.

‘You listen to me, George. I won’t have my daughter entrusted to a machine – and I don’t care how clever it is. It has no soul, and no one knows what it may be thinking. A child just isn’t made to be guarded by a thing of metal.’

Weston frowned, ‘When did you decide this? He’s been with Gloria two years now and I haven’t seen you worry till now.’

‘It was different at first. It was a novelty; it took a load off me, and – and it was a fashionable thing to do. But now I don’t know. The neighbors—’

‘Well, what have the neighbors to do with it? Now, look. A robot is infinitely more to be trusted than a human nursemaid. Robbie was constructed for only one purpose really – to be the companion of a little child. His entire “mentality” has been created for the purpose. He just can’t help being faithful and loving and kind. He’s a machine – made so. That’s more than you can say for humans.’

‘But something might go wrong. Some – some—’ Mrs Weston was a bit hazy about the insides of a robot, ‘some little jigger will come loose and the awful thing will go berserk and – and—’ She couldn’t bring herself to complete the quite obvious thought.

‘Nonsense,’ Weston denied, with an involuntary nervous shiver. ‘That’s completely ridiculous. We had a long discussion at the time we bought Robbie about the First Law of Robotics. You know that it is impossible for a robot to harm a human being; that long before enough can go wrong to alter that First Law, a robot would be completely inoperable. It’s a mathematical impossibility. Besides I have an engineer from US Robots here twice a year to give the poor gadget a complete overhaul. Why, there’s no more chance of anything at all going wrong with Robbie than there is of you or I suddenly going looney – considerably less, in fact. Besides, how are you going to take him away from Gloria?’