Полная версия

I Still Dream

It’s time for a new mixtape. I take a blank cassette, one of the few that’s not been used yet. I don’t want ghosting, where you can hear the sound of what was on the tape before sneaking through, like a reminder in the gaps between the songs; or worse, underneath it all, in the quiet parts. I’m going to ask Shawn for his address and send him it. He deserves a fresh one: a C90, forty-five minutes a side. The perfect length. I unwrap the plastic from it, and pull open the case. Everything is ritual. There’s nothing better than a clean inlay card. I pick my cassette brand because it has the best ones. Sony, always. Always. Maxell if you can’t get Sony, but the Sony ones, there’s enough space to write ten song names on each side, even though I only usually go to eight or nine. The songs have to fill the full hour and a half. No random cutting off, no breaks or pauses. That makes getting the track list perfect a bit of an act of clinical perfection. Sometimes, somebody from school will make me a tape, and they’ll be so amateurish. You’ll get to the end of side A – usually struggling through iffy taste, at best – and you’ll hear the start of a song you know is going to cut off because there just isn’t enough time to finish it, like I’ve got a sixth sense of song length. Then, you flip their tape over, and either they’ve repeated that song, because they think they have to, or they just give me the second half of it, which is next to useless. And there’s no art to their tapes. You have to pick the song at the end of a side carefully. Because the tape is thinner, or weaker, or something, and it distorts there, so you need to go quieter with it. Don’t pick something that will distort. You need to structure it like a proper album as well. Nobody ends on a single.

Track one: Radiohead. I think there’s a Radiohead on every tape I’ve ever made. Hard to pick the right song, though. It needs to be something rare enough that it’s not obvious, but not so weird it sounds freakish. The first song is the most important choice you’ll make. Most important apart from the last one, that is.

I listen to their songs, to the first few moments of every song. Settle on the one I’m going to use – a B-side, but it was also on the soundtrack to Romeo & Juliet, which isn’t me dropping a message, but then also it kind of is. I sync the tapes up, and I press play on one, record on the other. Let them go, let the sound flow across while I listen to it. I picture it, for a second: not as data being copied over, but as those sound waves. Copying the intent, the emotions, the performances. An act of creation.

Track two is even harder. This is where you can lose your listener; where you need to pin them to their headphones. This is where you play the single.

I go for an old song. Something with meaning. My fingers flick through the cassettes, rest on my Kate Bush tape. My dad recorded this for me, from his vinyl. It’s still got the crackle, this tiny skip at the end. I put on my favourite song from it – I still dream, the first line goes – and that’s the one. I still dream of Organon.

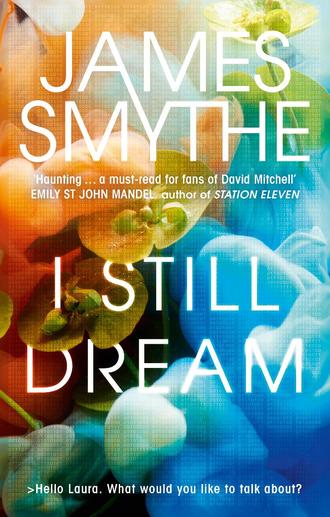

I named my imaginary friend after the song. I dreamed of him, and then there he was. So when I was looking for a name for my bit of software, it seemed to be the only logical choice. I told myself I’d change it, but I never did. It stuck.

The screen changes to a blank space; slightly off-white, like a very, very light grey. It’s calming, which is what I was going for. In the middle of the off-white there’s a text box, just sort of floating there. Some words fade into it: the ones I’ve programmed the software to start with every time.

> Hello Laura. What would you like to talk about?

So I do what I’ve done every night of my life for the last six months: I tell my computer what I’ve done today, what’s happened and what I’ve felt. Everything, because that’s what the point of Organon is. Somewhere to log my memories, to keep them all recorded. To get my thoughts out, and to see them there. And kind of poke them, as well.

Then, when I’ve told it about school and Shawn’s emails and the BT bill and my parents shutting me off from the Internet, Organon asks me questions.

> How does getting an email from Shawn make you feel?

> Don’t you think your mother is only trying to help?

> Why do you hurt yourself?

I remember going to have casual-sit-down-cup-of-tea-and-a-chats – that’s what Mum called them, because she didn’t want to admit that we were in therapy – with this woman, in the months after my dad went missing. She lived near the park, only a few streets away from home, and every time I saw her she made me a mug of hot chocolate, even when it was sweltering outside, and we went and sat in her conservatory and talked about how I was feeling. Back then, I thought she was just a nice lady who was taking an interest. I didn’t understand what she was actually doing. How much it made a difference, or how much it felt like it did. And that’s what Organon is. That’s what it does. It doesn’t judge you. It just asks questions, and you give it answers. It won’t tell you if you’re right or wrong. I remember the woman – I can’t remember her name, but I can smell the chocolate, taste the nutty biscuits that felt like they were almost so full of health-food stuff they might be good for me – saying, How does that make you feel? But not telling me how it should. There wasn’t a wrong answer. That’s Organon, kind of. Almost. But then, sometimes, it tries to help you see what you’re talking about. If you’ve got a lot to say, it’ll dig deeper. If you use a lot of key phrases, it’ll work out what’s important, and keep nudging in that direction. That’s what I want it to be able to do, in the end. Somebody – something – you can just spill to, get everything out, and hopefully get something back. Maybe it’ll help you work out who you are. If it can understand you, it can do that, I suppose.

I hope.

Thing is, the therapist would forget. You’d tell her something, and sometimes you’d have to tell her again. And it was obvious that it wasn’t her helping me; it was me helping myself, after a while. I was seven years old, and even I could tell that. That’s where Organon improves on things, or can. The real beauty of a computer – where they’re better than us, even – is that it’ll remember something for ever, if you want it to.

TUESDAY

Tuesdays are almost the worst, because they never contain any surprises. Monday, you’ve had the weekend for things to change. Tuesdays, all you’ve got is the drabness of a Monday night separating you from the stasis of the day before. Wake up to the stupid DJ on the radio, playing songs I like and talking over them, or songs that I don’t like and I can’t understand why he’s playing them. On Tuesdays, both Mum and Paul start work slightly too early to drive me to school, so I walk in. I stop on the way to get a croissant from the stand in the shopping centre. Or, sometimes, if I’m late, I get a Double Decker from the Londis. Double maths to start, then after break it’s double art, then lunch, and then our whole year’s afternoon is given over to the brilliant ambiguity of something called Reading Time, which basically means either getting homework done, or finding somewhere quiet in school and dicking about until a teacher walks in on you and tells you to stop.

It sucked hard, until I found out the Computer Lab was empty. There are no classes in here after lunch, which feels less like luck than fate: giving me somewhere that I actually want to go, where nobody else will be. Sometimes there will be some people working on geography coursework or something, but usually I’m alone. Or maybe one of the Michaels will be in there, but if they are, they’re playing Civilization, and they don’t pay any attention to what I’m up to.

Mr Ryan is there, as well. He used to be a software designer. He started off working for IBM in America, then a few other companies. You can still hear the American in his accent, sometimes. When he says, Sure. That’s a dead giveaway. Shore, shore. And, amazingly, he’d heard of my dad. He showed me an article about him in a book one time: ‘Daniel Bow, programming our intelligent future!’

Mr Ryan was the first person I ever told about Organon. He sat there, nodding away – that’s a real teacher tactic, to sit and nod; and sometimes, to do this cat’s cradle thing with the hands, under the chin – and then he rubbed his beard and stretched open his mouth, as if he was yawning. That’s when he offered to help me with the coding, if I needed it. He’s not as good as some of the coders I’ve found on the Internet, but it’s useful, having somebody to show my work to.

He’s sitting behind his desk when I walk in. A few Year 9 girls are here doing a project, laughing at something on the screen. There’s a photograph of a cat, and they’re drawing over it with the painting software. Giving it eyebrows. Mr Ryan rolls his eyes at them, and that makes me smile. It’s good. He acts like I’m a proper human, even though I’m into this stuff. Some teachers are funny about it, when you tell them that you want to work with computers. Shouldn’t you be outside and doing something more productive, all that stuff. Yeah: because running’s a job.

‘You going to show me where you’re up to with her?’ He calls Organon her. I’ve always assumed it’s an It. Seems a bit weird to think of it as a boy or a girl. ‘Show me what she’s got?’ I plug the zip drive into the back of the main computer, and start copying the file over. The little bar creeps along.

‘I didn’t get much done last week,’ I say. ‘Too much homework.’

‘But you got some?’

‘A little bit.’ I don’t say: Oh my God so much and I don’t want to tell you how much but in order to achieve it I nearly broke myself. Almost every night I get three hours or so in, when the rest of the house has gone to bed. I’m averaging six hours’ sleep. I think it’s enough. Apparently, Churchill only slept for five hours a night, and he ran a country. He fought a war, and what am I doing? I’m coding a therapist and rushing through my homework.

‘What say we open her up, look at her code?’

‘I suppose,’ I say. He likes to see how I built the software. He always says how out of touch he is, how the languages have moved along since his day. I don’t tell him that I learned all of this from books that used to be my dad’s, so they’re aeons old anyway. Probably the ones that Mr Ryan used, back in the day. He doesn’t get to see the databases, though. None of the stuff I’ve written into Organon, the things it’s given me advice on. They’re on the computer at home. I don’t let those out of the house.

‘So, where are we?’ I like Mr Ryan, but he says we like Organon’s the combined effort of our ideas. He’s helped me, and I’ll thank him if I ever manage to do anything with this, but Organon is mine. ‘Is she learning?’

‘It’s asking more questions. I’ve changed the parameters about when it can ask you stuff, interrupt, things like that.’

‘But you’re programming the words in?’

‘Obviously,’ I say. We had an argument, a few weeks after I first showed him Organon. He told me it wasn’t an actual artificial intelligence, and I told him he was wrong. Because it is: it understands what questions to ask, and when to ask them; when it’s gone too far, and when it’s not gone far enough. All the work I’ve done, it’s about understanding. Trying to make it understand when it can help, and how it can help. I explained that to Mr Ryan, and he said, But that’s not an AI. An AI can play chess, or it’ll launch nukes or something. He smiled then, but I didn’t think it was very funny. I had to explain that everything is artificial intelligence, really. Every bit of software. He didn’t understand, though, because Organon doesn’t do the things he expects. I didn’t say: Well, that’s how long it’s been since you’ve worked in software, then; and how little you actually understand. The week after that, I caught him reading Ray Kurzweil.

We haven’t had that discussion again since.

‘This thing’s amazing.’ He sits down, nudges me slightly to one side. He points his fingers – bitten-down fingernails, and I bite my fingernails, but not like this, these are right down to the quick, horrible stubby things digging into the flesh – at the code. ‘This is where you put the questions in?’

‘Yeah,’ I say, and he breathes in, nods along a few times. Puts his fingers up to his lips, like he’s making the shape of a gun, the barrel at his mouth. He’s got something to ask, and I know I’m not going to like it, because he’s nervous, but I can’t stop him.

‘Listen, I’ve been thinking. How I might actually be of, you know, real help. To you; to Organon. In the real world, software goes through beta testers.’ He pronounces it bayder. ‘So, you get people to use it, to work with it. Let it do its thing, and you get to use the results. That’s how you can make it better, you know? I’m thinking that it could be useful to you.’ He wants me to give Organon over to him. Shit, shit. I don’t know what to say. He’s a teacher. He’s a teacher, and he knows about this stuff, but I want to say no. I want to. ‘So,’ he says, and I wonder: can he tell that I’m not happy about this? Because I’m trying to make my body tell that to him as much as I can. ‘So why not let me take her home. Let me try her out, as she’s meant to be tried. It’ll be useful, because I’ll get to see what she’s really capable of, and you’ll give her a chance to stretch her legs.’

All I can think is, there’s something really icky about him talking about it as a her.

‘I don’t know,’ I say. I don’t say: I don’t want you to, and I don’t need you to. My elbow, the scar there, itches. I can feel it scabbing over; the skin trying to heal, trying to grow back as something like what it used to be. Something like itself.

‘I think you’ll really benefit from it. I might try something that you haven’t expected, find a bug you didn’t know about. And it’ll be so much easier for me to write you a recommendation when you’re doing your UCAS forms, if I know exactly what you’re capable of.’ There it is. The bribe. It’s hard to get onto programming courses if you don’t have experience, and he’s worked in computers. His support on my application would probably help. ‘Besides which, I might get some benefit from talking to her! That’s the point of Organon, right? Real world experience, Laura.’ I don’t know what he’d want to talk to it about. There are rumours about him, but there are rumours about every teacher. And his aren’t nearly as nasty as some about the other members of staff. Some of them, the rumours never end, and they escalate. But Mr Ryan seems like he’s pretty together. But then, he’s not married, and he is pretty old. Mum’s age, I think. Flecks of grey in his beard. ‘Listen, it’s your project, Laura. You do what you want. But sometimes we can’t see the wood for the trees, and we need somebody who might be able to give us a pair of binoculars and an axe.’

‘Okay,’ I say. My elbow kills when I say it, and when he smiles, this beaming thing, bigger than I’ve ever seen from him before.

‘You won’t regret it,’ he tells me. ‘Seriously, a bit of time with her, little play with her code—’ He must see my face then, because he changes his words straight away. ‘I can write some notes for you, give you some suggestions for what you do moving forward. That’s it.’

‘Thanks,’ I say. He shifts back in his chair, leaving the keyboard free for me, and I open up Organon. The white room, the fade in of the text box.

> What would you like to talk about?

‘If you think of any questions I can get it to ask?’

‘I will absolutely tell you,’ he replies.

‘Just give me ten minutes with it,’ I say. ‘I need to set it up to work on your computer.’

‘Sure,’ he replies. He smiles, and then walks over to the Year 9s, and he asks them about the pictures they’re drawing on. He keeps glancing over, so I’m quick. I have to be quick. I open the code, and I write in a homing device. It’ll email me bug reports. I make it so you have to be on the Internet to even run Organon, and then I save everything. ‘All done?’ Mr Ryan asks. I nod. All done.

The main home computer, the one that my mum uses, is ancient. You can’t even plug the modem into it, that’s how old it is; and her printer is this ridiculous dot-matrix thing that takes about ten minutes to print a page, that screams like there’s something trapped inside it as it pukes up its pages. But she won’t get rid of it. She’s used to it, she says. It was my dad’s, way back. She doesn’t have much of his stuff around, just a few boxes in the loft; and there aren’t any pictures of him on display or anything. The computer is it.

I’ve got a photograph of me sitting on his lap in front of it, that he took the day before he left. He held the camera himself and took it, stretching his arm out to capture us both. He looks sad, and I look oblivious. The last picture I have of him. My hands are on the keyboard, and there’s a flag up on the screen, horrible colours, like the Union Jack, but beaten-up and bruised to purples and greens. We’re both smiling. That’s the picture where, if anybody ever sees it, they tell me that I look a bit like him; something in the eyes, they say. And I always think: Well, his eyes look so sad in that, so what does that say about me?

Mum does all her work on this ancient piece of software that he built for her way back when, this word processor that’s years behind what you can do in Microsoft Word. The computer doesn’t even run Windows. And now it won’t even turn on. She’s been moaning about it for weeks. I reckon, I do this now, fix it for her, that might get me some bonus Internet time. A little bit of leniency.

I press the power button. Nothing happens. I unplug it and wait twenty seconds. There’s memory in there attached to a tiny little battery, and you have to wait for that to wipe itself sometimes before it’ll work. Then I plug it in, try again. Nothing.

Only, it’s not actually nothing. When I get close to unplug it again, before opening it up, I notice that there’s this weird hum coming from it. Like, this scratching, almost. Probably the hard drive trying to start. I don’t even know what a hard drive from the 1980s looks like. I reach around the back to find the stupid twiddly fussy knobs that take far too long to undo, and which don’t seem to want to turn, they’ve been stuck in place that long. I get them all out, but the case seems like it’s jammed.

I spin the computer around, to check that I got them all, get a better view. Sometimes there’s one of them hidden, just out of reach. And there is, sure enough, right through the manufacturer’s label. The name of the company who put this together, handwritten in neat blue ink on a yellowing white sticker. Bow, it says. The company my father used to work for, or run, or whatever. His father’s company, my grandfather’s company. Makes sense this would be one that they built.

The back of the box falls off, then, flips down, and I can see inside it. It’s so, so dusty. Too much to blow it away, but I have to try. Breathe in, puff out this stupid fake-sounding breath into the box. The fan doesn’t even turn, so I reach in, just with my fingertips, and pull the dust out in clumps. The inside of this thing is crazy. I’ve built my own PC now – the one that I used to create Organon, that’s mine, parts ordered from a website I saw in a magazine, paid for with money that Mum and Paul gave me for my fifteenth birthday – but it looks nothing like this. Everything in here is massive and clumsy and crammed in. The cables are worn and frayed. I try to see better, to get the rest of the case off, but it’s stuck hard.

I grab the base between both hands, and I shake it.

Something moves. It rockets towards me, right out of the darkness. Up to my fingers, and across my hand, onto my forearm, and I scream, flicking my arms upwards in panic. Whatever it is hits something – the wall, the ceiling, I don’t know – and there’s a thud, then another when it lands on the floor in the far corner of the room. It’s a mouse, thin and brown, a tiny skeleton in patchy fur. I see a breath taken; a chest rise and fall. Stub dashes – as much as a seventeen-year-old cat can dash, more of a hurried wobble – into the room, and seems to sniff the air; but then drops back to fake nonchalance, even though his fur’s prickled; as if his body, muscle memory or something, remembers how the chase is meant to go, but that this mouse really isn’t giving him anything to work with.

‘Get away,’ I say to him, and I make that Psssshhh! noise that my mum makes sometimes. He backs away slowly while I squat down and look at the mouse. ‘Little dude,’ I say, ‘poor little guy. I’m sorry.’ I pick him up, cupping him in my hands. He’s stopped breathing; I wonder if he even was after he landed or if that was just a trick of the light. I go down the stairs, out the kitchen door, and walk carefully to the bottom of the garden. I can see the Tube line through the fence; a Heathrow train just pulling into the station. I put him in the tall grass right by the fence, deep into it. Maybe Stub’ll find him anyway, and do some weird old-cat-eats-his-already-dead-prey thing. Or, maybe the mouse will just decompose. Go back into the ground.

When I get back inside, I go through the house using my sore elbow to open doors and to turn the tap on, so I can wash my hands. When that’s done, I take a shower. I don’t know if mice carry diseases, but I don’t want to risk it. I’m lathered up when there’s a bang. Cars backfiring, and fireworks. That’s what you blame loud noises on in London. Chances are, though, it’s Stub. He keeps falling off things, wobbling around. Last week he went for a wee on the kettle. Paul’s got this look in his eye when he strokes Stub now. None of us are talking about what it means, but we know, we all know.

I go into the hallway, towel wrapped around me. No more bangs, but I can hear a crackling, now. Like feet treading on dead leaves. And there’s a smell, something burning. Fireworks, bonfires. But Guy Fawkes’ night isn’t for a couple of weeks yet.

Another bang: it’s coming from the computer. There are flames sparking from the power supply. Didn’t I turn it off? Did I forget? I’m a total fucking moron. Inside my head, the voice screams: You’re going to be so dead when Mum finds out; when you have to tell her. Oh, that computer you asked me to look at? It exploded because I’m an idiot. I yank the plug from the wall, get water from the bathroom, in the little toothbrush cup, because that’s all I can find, and I run back and pour it over the sparks. The fizzle as the flames go out is so weirdly satisfying; the sound of something terrible happening suddenly gone. Makes me think of my matches. Then there’s smoke, and steam. I don’t even know the difference. I bend down, to peer into the computer. The motherboard is totally blown. The fire looks like it was caused by one of the frayed wires – which, I realise now, were probably nibbled; thanks, Mr Mouse! – and it’s blackened half of the inside, best I can see. I get the screwdriver and reach in. I can save the hard drive, I think. It’s hot inside the box, but I can still manage to undo the screws that hold the drive in. It’s enormous, and I think it’ll just be a casing at first, but then when I manage to drag it out, it’s the hard drive itself. Takes about three or four times the room that mine upstairs does, and this one is so much smaller inside. It’s got 10 megabytes printed on the side, which is insane. I couldn’t even fit Organon onto it if I tried.

I take the drive upstairs and clear a space for it on my desk. Move my joss stick burner, some computer magazines, a few issues of the NME and Select that I’ve been cutting up for the pictures. I’ll need to save Mum’s spreadsheets, I’m sure. God knows if she’ll be able to open them any other way.

Then the door downstairs slams – I recognise the sound this time, so different from the bang when the computer exploded I don’t even know how I confused them – and Mum shouts ‘Hello,’ and I shout it back. I scratch at my elbow, until the scab comes off again, because that’s all I’ve got time to do before she comes up to see me; and I can feel the warmth of the blood inside my jumper when I press on it.