полная версия

полная версияNotes and Queries, Number 206, October 8, 1853

Various

Notes and Queries, Number 206, October 8, 1853 / A Medium of Inter-communication for Literary Men, Artists, Antiquaries, Genealogists, etc

Notes

NOTES ON NEWSPAPERS: "THE TIMES," DAILY PRESS, ETC

A newspaper, rightly conducted, is a potent power in promoting the well-being of universal man. It is also a highly moral power—for it quickens mind everywhere, and puts in force those principles which tend to lessen human woe, and to exalt and dignify our common humanity. The daily press, for the most part, aims to correct error—whether senatorial, theological, or legal. It pleads in earnest tones for the removal of public wrong, and watches with a keen eye the rise and fall of great interests. It teaches with commanding power, and makes its influence felt in the palace of the monarch, as well as through all classes of the community. It helps on, in the path of honorable ambition, the virtuous and the good. It never hesitates or falters, however formidable the foe. It never crouches, however injurious to itself the free and undisguised utterance of some truths may be. It is outspoken. When the nation requires them, it is bold and fearless in propounding great changes, though they may clash with the expectations of a powerful class. It heeds the reverses to which a nation is subjected, and turns them to good account. It does not abuse its power, and is never menaced. It is unshackled, and therefore has a native growth. It looks on the movements of the wide world calmly, deliberately, and intelligently. We believe the independency of the daily press can never be bribed, or its patronage won by unlawful means. Its mission is noble, and the presiding sentiment of the varied intellect employed upon it is "the greatest good to the greatest number." It never ceases in its operations. It is a perpetual thing: always the same in many of its aspects, and yet always new. It is untiring in its efforts, and unimpeded in its career. We look for it every day with an unwavering confidence, with an almost absolute certainty. Power and freshness are its principal characteristics; and with these it combines a healthy tone, a fearless courage, and an invincible determination. That it has its imperfections, we do not deny—and what agency is without them? It is not free from error, and no estate of the realm can be. The purity of the public press will be increased as Christianity advances. There is no nation in the world which can boast of a press so moral, and so just, as the daily newspaper press of Great Britain. The victories it achieves are seen and felt by all: and when compared with the newspaper press of other countries, it has superior claims to our admiration and regard.

Taking The Times as the highest type of that class of newspapers which we denominate the daily press, these remarks will more particularly apply. The history of such a paper, and its wonderful career, is not sufficiently known, and its great commercial and intellectual power not adequately estimated. The extinction of such a journal (could we suppose such a thing,) would be a public calamity. Its vast influence is felt throughout the civilised world; and we believe that influence, generally speaking, is on the side of right, and for the promotion of the common weal. It is strange that such an organ of public sentiment should have been charged with the moral turpitude of receiving bribes. That it should destroy its reputation, darken its fair fame, and undermine the very foundation of its prosperity, by a course so degrading, we find it impossible to believe. We feel assured it is far removed from everything of the kind: that its course is marked by great honesty of purpose, and its exalted aim will never allow it to stoop to anything so beneath the dignity of its character, and so repugnant to every sense of rectitude and propriety. It is no presumption to assert that, under such overt influences, it remains unmoved and immovable; and to reiterate a remark made in the former part of this article, "its independency can never be bribed, or its patronage won by unlawful means." Looking at it in its colossal strength, and with its omnipotent power (for truth is omnipotent), it may be classed, without any impropriety, among the wonders of the world.

Allow me to give to the readers of "N. & Q." the following facts in connexion with The Times, and on the subject of newspapers generally. They are deserving of a place in your valuable journal. There were sold of The Times on Nov. 19, 1852, containing an account of the Duke of Wellington's funeral, 70,000 copies: these were worked off at the rate of from 10,000 to 12,000 an hour. The Times of Jan. 10, 1806, with an account of the funeral of Lord Nelson, is a small paper compared with The Times of the present day. Its size is nineteen inches by thirteen: having about eighty advertisements, and occupying, with woodcuts of the coffin and funeral car, a space of fifteen inches by nine. Nearly fifty years have elapsed since then, and now the same paper frequently publishes a double supplement, which, with the paper itself, contains the large number of about 1,700 advertisements.1 54,000 copies of The Times were sold when the Royal Exchange was opened by the Queen; 44,500 at the close of Rush's trial. 1828, the circulation of The Times was under 7,000 a day; now its average circulation is about 42,000 a day, or 12,000,000 annually.2 The gross proceeds of The Times, in 1828, was about 45,000l. a year: and, from an article which appeared twelve months ago in its columns, it now enjoys a gross income equal to that of a flourishing German principality.

We believe we are correct when we assert, that there were sold of the Illustrated London News, with a narrative of the Duke's funeral (a double number), 400,000 copies. One newsman is said to have taken 1000 quires double number, or 2000 quires single number: making 27,000 double papers, or 54,000 single papers (twenty-seven papers being the number to a quire), and for which he must have paid 1075l3. It is a remarkable fact, that Manchester, with a population of 400,000, has but three newspapers; Liverpool, with 367,000, eleven; Glasgow, with 390,000, sixteen; Dublin, with but 200,000, no less than twenty-two. The largest paper ever known was published some years ago by Brother Jonathan, and called the Boston Notion. The head letters stand two inches high; the sheet measures five feet ten inches by four feet one inch, being about twenty-four square feet; it is a double sheet, with ten columns in each page; making in all eighty columns, containing 1,000,000 letters, and sold for 3½d. In the good old times, one of the earliest provincial newspapers in the southern part of the kingdom was printed by a man named Mogridge, who used to insert the intelligence from Yorkshire under the head "Foreign News."

It is curious to search a file of old newspapers. It is seldom we have the opportunity of doing so, because we rarely preserve them in consecutive order. It is easy to keep them, and would repay the trouble, and their value would increase as years rolled on. Such reading would be very interesting, and more so than we can at all imagine. It is a history of every day, and a record of a people's sayings and doings. It throws us back on the past, and makes forgotten times live again. Some of the early volumes of The Times newspaper, for instance, would be a curiosity in their way. We should read them with special interest, as reflecting the character of the age in which they appeared, and as belonging to a series exercising a mighty influence in moulding and guiding the commercial and political opinions of this great nation. The preservation of a newspaper, if it be but a weekly one, will become a source of instruction and amusement to our descendants in generations to come.

H. M. Bealby.North Brixton.

"IN QUIETNESS AND CONFIDENCE SHALL BE YOUR STRENGTH."

There is an old house in the "Dom Platz," at Frankfort, in which Luther lived for some years. A bust of him in relief is let into the outer wall; it is a grim-looking ungainly effigy, coarsely coloured, and of very small pretensions as a work of art; but evidently of a date not much later than the time of the great Iconoclast. Round the figure, the following words are deeply cut: "In silentio et in spe, erit fortitudo vestra." Can any of your readers tell me whether any particular circumstance of Luther's life led him to adopt this motto, or otherwise identified it with his name; or whether the text was merely selected by some admirer after his death, to garnish this memorial?

In either case it is not uninteresting to notice, that this passage of Scripture has been employed more than any other as the watchword of that religious movement in the English Church which we are accustomed to associate with Oxford and the year 1833. It forms the motto on the title-page of the Christian Year; it has been very conspicuous in the writings of many eminent defenders of the same school of theology, and it is thus alluded to by Dr. Pusey in the preface to that celebrated sermon on the Eucharist, for which he received the University censure:

"Since I can now speak in no other manner, I may in this way utter one word to the young, to whom I have heretofore spoken from a more solemn place; I would remind them how almost prophetically, sixteen years ago, in the volume which was the unknown dawn and harbinger of the re-awakening of deeper truth, this was given as the watchword to those who should love the truth, 'In quietness and confidence shall be your strength.' There have been manifold tokens that patience is the one great grace which God is now calling forth in our church," &c.

I will not here inquire which of the two great religious revolutions I have mentioned has been more truly characterised by the spirit of this beautiful and striking text, but perhaps some of your readers will agree with me in thinking that the coincidence is at least a note-worthy one; and not the less so, because it was probably undesigned.

Joshua G. Fitch.BINDERS OF THE VOLUMES IN THE HARLEIAN LIBRARY

In Dr. Dibdin's Bibliographical Decameron, 1817, vol. ii. p. 503., he thus introduces the subject:

"The commencement of the eighteenth century saw the rise and progress of the rival libraries of Harley and Sunderland. What a field, therefore, was here for the display of the bibliopegistic art! Harley usually preferred red morocco, with a broad border of gold, and the fore-edges of the leaves without colour or gilt. Generally speaking, the Harleian volumes are most respectably bound; but they have little variety, and the style of art which they generally exhibit rather belongs to works of devotion."

In a note on the above passage, Dibdin adds:

"I have often consulted my bibliomaniacal friends respecting the name of the binder or binders of the Harleian Library. Had Bagford or Wanley the chief direction? I suspect the latter."

If Dr. Dibdin and his "bibliomaniacal friends" had not preferred the easy labour of looking at printed title-pages to the rather more laborious task of examining manuscripts, they might readily have solved the Query thus raised by referring to Wanley's Autograph Diary, preserved in the Lansdowne Collection, Nos. 771, 772, which proves that the binders employed by Lord Oxford were Christopher Chapman of Duck Lane, and Thomas Elliot. Very many entries occur between January 1719-20 and May 1726, relative to the binding both of manuscripts and books in morocco and calf; and it appears, in regard to the former material, that it was supplied by Lord Oxford himself. Some of these entries will show the jealous care exercised by honest Humphrey Wanley over the charge committed to him.

"25th January, 1719-20. This day having inspected Mr. Elliot's bill, I found him exceedingly dear in all the work of Morocco, Turkey, and Russia leather, besides that of velvet.

"28th January, –. Mr. Elliot the bookbinder came, to whom I produced the observations I made upon his last bill, showing him that (without catching at every little matter) my Lord might have had the same work done as well and cheaper, by above 31l. He said that he could have saved above eight pounds in the fine books, and yet they should have looked well. That he now cannot do them so cheap as he rated them at; that no man can do so well as himself, or near the rates I set against his. But, upon the whole, said he would write to my Lord upon the subject.

"13th July, 1721. Mr. Elliot having clothed the CODEX AVREVS in my Lord's Morocco leather, took the same from hence this day, in order to work upon it with his best tools; which, he says, he can do with much more convenience at his house than here.

"19th January, 1721-22. Mr. Chapman came, and received three books for present binding. And upon his request I delivered (by order) six Morocco skins to be used in my Lord's service. He desires to have them at a cheap price, and to bind as before. I say that my Lord will not turn leather-seller, and therefore he must bring hither his proposals for binding with my Lord's Morocco skins; otherwise his Lordship will appoint some other binder to do so.

"17th September, 1725. Mr. Elliot brought the parcel I last delivered unto him, but took one back to amend a blunder in the lettering. He said that he has used my Lord's doe-skin upon six books, and that they may serve instead of calf; only the grain is coarser, like that of sheep, and this skin was tanned too much.

"23rd December, 1725. Mr. Chapman came, but I gave him no work; chiding him for being so slow in my Lord's former business, which he had frequently postponed, that he might serve the booksellers the sooner."

μ.FRENCH VERSE

In the Diary of T. Moore I lately read, with some surprise, the following passages:

"Attended watchfully to her [Mdlle Duchesnois] recitative, and find that in nine verses out of ten 'A cobbler there was, and he lived in a stall' is the tune of the French heroics."—April 24, 1821.

"Two lines I met in Athalie; how else than according to the 'Cobbler there was,' &c., can they be repeated?

'N'a pour servir sa cause et venger ses injures,Ni le cœur assez droit, ni les mains assez pures.'"—May 30, 1821.Now, if this be the mode of reading these lines, I confess all my ideas are erroneous with respect to French poetry. I have always considered that though hemistichs and occasionally whole lines occur in it, which bear a resemblance to the Spanish Versos de Arte Mayor, the anapæstic measure of "A Cobbler" is quite foreign to it. I may, however, be mistaken; and it is in the hope of eliciting information on the subject that I send these few remarks to "N. & Q." Should it appear that I am not wrong, I will on a future occasion endeavour to develop my ideas of the French rhythm; a subject that I cannot recollect to have seen treated in a satisfactory manner in any French work.

Bishop Tegnér, the poet of Sweden, seems also to have differed in opinion with Moore respecting the rhythm of French poetry, for he compares it to the dancing of a deaf man, who forms his steps accurate, but who does not keep time. Both are alike mistaken, in my opinion; and their error arises from their judging French poetry by rules that are foreign to it. The rhythm of French verse is peculiar, and differs from that of any other language.

Thos. Keightley.A SPANISH PLAY-BILL

Though not much a frequenter of theatres of late, I was recently induced, by the flourishing public announcements, to go to Drury Lane Theatre; with the chance, but scarcely in the hope, of seeing what I never yet have seen, a perfect Othello. Alas! echo still answers never yet. But yours are not the pages for dramatic criticism.

As my bill lay before me, I could not help thinking what an execrably bad taste our modern managers show in the extravagant and ridiculous announcement of the splendour of the star you come to contemplate! If Mr. Brooke have great merit, he needs not all this sound of trumpets; if he have it not, he is only rendered the more contemptible by it. I have some of the play-bills of John Kemble's last performances before me, and there is none of this fustian: the fact, the performance, and the name are simply announced. If our taste improves in some respects, it does not in this; it is a retrogression—a royal theatre sinking back into the booth of a fair. Shakspeare's and Byron's texts have been converted into the showman's explanations of panoramas: to what vile uses they may be next applied, there is no guessing. Poor Shakspeare! how I have pitied him, and you too, Mr. Editor, as I have seen him for so many months undergoing the operation of the teazle in "N. & Q.!" I hope there will be soon an end of this "skimble stuff," "signifying nothing."

But my observation upon the Drury Lane play-bill reminded me of one I have in my common-place book; and, as a correspondent and reader of "N. & Q.," I think it my duty to send it:

A Spanish Play-bill, exhibited at Seville, 1762"To the Sovereign of Heaven—to the Mother of the Eternal World—to the Polar Star of Spain—to the Comforter of all Spain—to the faithful Protectress of the Spanish Nation—to the Honour and Glory of the Most Holy Virgin Mary—for her benefit, and for the Propagation of her Worship—the company of Comedians will this day give a representation of the Comic Piece called—

NanineThe celebrated Italian will also dance the Fandango, and the Theatre will be respectably illuminated."

William Robson.Stockwell.

SHAKSPEARE CORRESPONDENCE

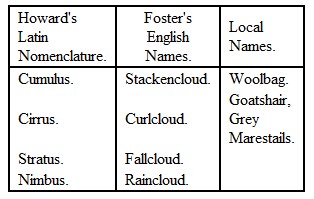

The Meteorology of Shakspeare.—A treatise might be written on meteorology, and might be illustrated entirely by passages taken from the writings of "the world's greatest poet." "N. & Q." may not be the fitting medium for a lengthened treatise, but it is the most proper depository of a few loose Notes on the subject. Those who study Shakspeare should, to understand him, thoroughly study Nature at the same time: but to our meteorology. Recent observers have classified clouds as under:

There are composite forms of cloud, varieties of the above, which need not be noticed here. The Cumulus is the parent cloud, and produces every other form of cloud known, or which can exist. Mountain ranges and currents of air of unequal temperatures may produce visible vapour, but not true cloud.

Cumulus. This cloud is always formed at "the dew point." The vapour of the lower atmosphere, at this elevation, is condensed, or rendered visible. In fog the dew point is at the surface of the earth; in summer it may be several thousands of feet above. The Cumulus cloud forms from below. The invisible vapour of the lower atmosphere is condensed, parts with its thousand degrees of latent heat, which rush upwards, forcing the vapour into the vast hemispherical heaps of snowy, glittering clouds, which, seen in midday, appear huge mountains of clouds; the "cloud-land" of the poet, floating in liquid air. The Cumulus cloud is ever changing in form. Cumulating from a level base, the top is mounting higher and higher, until the excessive moisture is precipitated in heavy rain, hail, or thunder showers.

The tops of the Cumulus, carried away by the upper equatorial currents, form the Cirrus clouds, which clouds must be frozen vapour, as they are generally from twenty to thirty thousand feet above the level of the sea. The base of the Cumulus is probably never more, in England, than five thousand feet high, rarely this. The Nimbus is the Cumulus shedding its vapour in rain; and the Stratus is the partially exhausted and fading Nimbus.

Poets in all ages have watched the clouds with interest; and Shakspeare has not only correctly described them, but has, in metaphor, used them in some of his sublimest passages. Ariel will "ride on the curled clouds" to Prospero's "strong bidding task" that is, ride on the highest Cirrus cloud, in regions impassable to man. How admirably the raining Cumulus (Nimbus cloud) is described in the same play:

"Trinculo. Here's neither bush4 nor shrub, to bear off any weather at all, and another storm brewing. I hear it sing i' the wind: yond' same black cloud, yond' huge one, looks like a foul5 bumbard that would shed his liquor …

… Yond' same cloud cannot choose but fall by pailfuls."

Hamlet points to a changing Cumulus cloud, when he says to Polonius, "Do you see that cloud, that almost in shape like a camel?"

"Pol. By the mass, and 'tis like a camel, indeed.Ham. Methinks it is like a weasel.Pol. It is back'd like a weasel.Ham. Or like a whale?Pol. Very like a whale."But the finest cloud passage in the whole range of literature is contained in Antony and Cleopatra, painting, as it does, the fallen and wasting state of the emperor (Act IV. Sc. 12.):

"Ant. Eros, thou yet behold'st me?Eros. Ay, noble lord!Ant. Sometime we see a cloud that's dragonish:A vapour, sometime, like a bear, or lion,A tower'd citadel, a pendant rock,A forked mountain, or blue promontoryWith trees upon't, that nod unto the world,And mock our eyes with air. Thou hast seen these signs:They are black vesper's pageants.Eros. Ay, my lord.Ant. That which is now a horse, even with a thought,The rack dislimns; and makes it indistinct,As water is in water.Eros. It does, my lord.Ant. My good knave, Eros, now thy captain isEven such a body: here I am Antony;Yet cannot hold this visible shape, my knave."Those who wish to understand this sublime passage must watch a bank of Cumulus clouds at the western sky on a summer's evening. The tops of the clouds must not be more than five or ten degrees above the apparent horizon. There must also be a clear space upwards, and the sun fairly set to the last stages of twilight. It will then be comprehended as to what is meant by "black vesper's pageants," and Warton and Knight will no more mislead by their note. It is only at "black vespers" that such a pageant can be seen, when the liberated heat of the Cumulus cloud is forcing the vapour into the grand or fantastic shapes indicated to the poet's eye and mind.

How truly does Antony read his own condition in the changing and perishable clouds. Shakspeare names or alludes to the clouds in more than one hundred passages, and the form of cloud is ever correctly indicated. Who does not remember the passages in Romeo and Juliet? Much more might be written on this subject.

Robert Rawlinson.At the Hull meeting of the British Association, Mr. Russell, farmer, Kilwhiss, Fife, read a paper on "The Action of the Winds which veer from the South-west to West, and North-west to North." This he wound up by a reference to Shakspeare, which may be worthy of noting:

"In concluding, I cannot help remarking that this circuit of the wind from SW. by W. to NW. or N., from our insular position, imparts to our climate its fickleness and inconstancy. How often will our brightest sky become suffused by the blackest vapours on the slightest breach of SW. wind, and the clouds will then disappear as speedily as they formed, when the NW. upper current forces their stratum of moist air to rise and mingle with the dryer current above. I do not know who first noticed and recorded this change of the wind from SW. to NW., but the regularity of the phenomenon must teach us that the law which it obeys is part of a grand system, and invites us to trace its action. I do not think it will be out of place to point out the fact that the great English poet seems to have been quite familiar with this feature of our weather, not only in its most striking manifestations in the autumn and winter months, to which he especially refers, but even in its more pleasant aspects of summer. Shakspeare likens the wind in this shifting to an individual who pays his addresses in succession to two fair ones—first he wooes the North, but in courting that frigid beauty a difference takes place, whereupon he turns his back upon her and courts the fair South. You will observe the lines are specially applied to the winter season—