полная версия

полная версияNotes and Queries, Number 79, May 3, 1851

Various

Notes and Queries, Number 79, May 3, 1851 / A Medium of Inter-communication for Literary Men, Artists, Antiquaries, Genealogists, etc

Notes

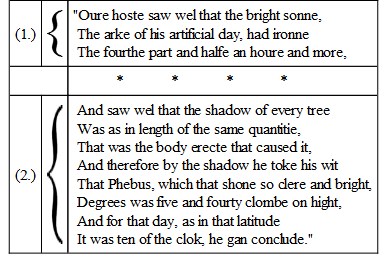

ILLUSTRATIONS OF CHAUCER NO. V

The Arke of Artificial Day.

Before proceeding, to point out the indelible marks by which Chaucer has, as it were, stereotyped the true date of the journey to Canterbury, I shall clear away another stumbling-block, still more insurmountable to Tyrwhitt than his first difficulty of the "halfe cours" in Aries, viz. the seeming inconsistency in statements (1.) and (2.) in the following lines of the prologue to the Man of Lawe's tale:—

The difficulty will be best explained in Tyrwhitt's own words:—

"Unfortunately, however, this description, though seemingly intended to be so accurate, will neither enable us to conclude with the MSS. that it was 'ten of the clock,' nor to fix upon any other hour; as the two circumstances just mentioned are not found to coincide in any part of the 28th, or of any other day of April, in this climate."—Introductory Discourse, § xiv.

In a foot-note, Tyrwhitt further enters into a calculation to show that, on the 28th of April, the fourth part of the day and half an hour and more (even with the liberal allowance of a quarter of an hour to the indefinite phrase 'and more') would have been completed by nine o'clock A.M. at the latest, and therefore at least an hour too soon for coincidence with (2.).

Now one would think that Tyrwhitt, when he found his author relating facts, "seemingly intended to be so accurate," would have endeavoured to discover whether there might not be some hidden meaning in them, the explaining of which might make that consistent, which, at first, was apparently the reverse.

Had he investigated with such a spirit, he must have discovered that the expression "arke of the artificial day" could not, in this instance, receive its obvious and usual meaning, of the horary duration from sunrise to sunset—

And for this simple reason: That such a meaning would presuppose a knowledge of the hour—of the very thing in request—and which was about to be discovered by "our hoste," who "toke his wit" from the sun's altitude for the purpose! But he knew already that the fourth part of the day IN TIME had elapsed, he must necessarily have also known what that time was, without the necessity of calculating it!

Now, Chaucer, whose choice of expression on scientific subjects is often singularly exact, says, "Our hoste saw that the sonne," &c.; he must therefore have been referring to some visible situation: because, afterwards, when the time of day has been obtained from calculation, the phrase changes to "gan conclude" that it was ten of the clock.

It seems, therefore, certain that, even setting aside the question of consistency between (1.) and (2.), we must, upon other grounds, assume that Chaucer had some meaning in the expression "arke of the artificial day," different from what must be admitted to be its obvious and received signification.

To what other ark, then, could he have been alluding, if not to the horary diurnal ark?

I think, to the Azimuthal Arch of the Horizon included between the point of sunrise and that of sunset!

The situation of any point in that arch is called its bearing; it is estimated by reference to the points of the compass; it is therefore visually ascertainable: and it requires no previous knowledge of the hour in order to determine when the sun has completed the fourth, or any other, portion of it.

Here, then, is primâ facie probability established in favour of this interpretation. And if, upon examination, we find that it also clears away the discrepancy between (1.) and (2.), probability becomes certainty.

Assuming, upon evidence which I shall hereafter explain, that the sun's declination, on the day of the journey, was 13° 26' North, or thirteen degrees and half,—the sun's bearing at rising, in the neighbourhood of London, would be E.N.E., at setting W.N.W.; the whole included arch, 224°; and the time at which the sun would complete one-fourth, or have the bearing, S.E. by E., would be about 20 minutes past nine A.M.,—thus leaving 40 minutes to represent Chaucer's "halfe an hour and more!"

A very remarkable approximation—which converts a statement apparently contradictory, into a strong confirmation of the deduction to be obtained from the other physical facts grouped together by Chaucer with such extraordinary skill!

On the other hand, it is impossible to deny that the "hoste's" subsequent admonition to the pilgrims to make the best use of their time, warning them that "the fourthe partie of this day is gon," seems again to favour the idea that it is the day's actual horary duration that is alluded to.

This can be only hypothetically accounted for by observing that in this, as in many other instances, Chaucer seems to delight in a sort of disguised phraseology; as though to veil his true meaning, and designedly to create scientific puzzles to exercise the knowledge and discernment of his readers.

A. E. B.Leeds, April 14. 1851.

FOREIGN ENGLISH—GUIDE TO AMSTERDAM

I doubt not many of your readers will have been as much amused as myself with the choice specimens of Foreign English enshrined in your pages. When at Amsterdam, some years since, I purchased a Guide to that city, which I regard as a considerable literary curiosity in the same line. It was published at Amsterdam, by E. Maascamp, in 1829, and contains from beginning to end a series of broken English, professing all the while to be written by an Englishman.

It commences with the following "Advertisement:"

"The city of Amsterdam—remarkable as being one of the chief metropoles of Europe, and as being in many respects the general market of whole the universe; justly celebrated for—its large interior canals, on both of their sides enlivened and sheltered by ranges of large, thick, and beautiful trees, and presenting, on large broad and neatly kept, most regularly pav'd quays, long chains of sumptuous habitations, or rather palaces of the principal and weathy merchants; moreover remarkable by its Museum for the objects of the fine arts, &c., its numberless public edifices adapted either to the cultivation of arts, or to the exertions of trade, or to establishments charitable purposes, or of temples of all manners of divine worship—the city of Amsterdam, we say," &c. It is dated "This 15the of Juin, 1829."

In page 14. the author gives us an account of his habits, &c.:—

"I live in Amsterdam since some considerable time I drink no strong liquors, nor do I smoke tobacco and with all this—I have not been attacked by those agues and fevers wh frequently reign here from the month of Juin to the end of the autumn: and twenty foreigners whom I know, do follow the same system, and are still as healthy as I myself; while I have seen a great many of natives taking their drams and smoking their pipes ad libitem, and moreover chawing tobacco in a quite disgusting manner, who," &c.

An Amsterdam Sunday, p. 42.:

"On sundays and holydays the shops and warehouses, and, intra muros, those of public entertainment are close: the devotees go to church, and sanctify the sabbath. Others go to walk outside the towngates: after their walk, they hasten to fine public-play-gardens, where wine, thea, &c. is sold. Neither the mobility remains idle at these entertainments. Every one invites his damsel, and joyously they enter play-gardens of a little less brilliancy than the former. There, at the crying sound of an instrument that rents the ear, accompanied by the delightful handle-organs and the rustic triangle, their tributes are paid to Terpsichore; every where a similitude of talents: the dancing outdoes not the musician."

Description of the Assize Court:

"The forefront has a noble and sublime aspect, and is particularly characteristical to what it ought to represent. It is built in a division of three fronts in the corinthic order: each of them consists in four raizing columns, resting upon a general basement, from the one end of the forefront to the other, and supporting a cornish, equally running all over the face; upon this cornish rests a balustrad, like the other pieces altogether of Bremen-hardstone. The middle front, serving for the chief entrance, is adorned with the provincial arms, sculpted by Mr. Gabriel, &c.... Every where a sublime plan, and exact execution is exhibited here, and the whole tends as much to the architects, who are the undertakers of it, as they have earned great praizes by building anew the burnt Lutheran church."

I will not trespass on your space by any further extracts; but these will suffice to show that my book is sui generis, and worth commemoration.

C. W. B.SEVEN CHILDREN AT A BIRTH THREE TIMES FOLLOWING

Your correspondent N. D.'s papers (Vol. ii., p. 459., and Vol. iii., p. 64) have reminded me of another remarkable instance of fecundity related by the well-known civil engineer Jan Adriaensz. Leeg-Water, in his Kleyne Chronycke, printed at Amsterdam in 1654:

"Some years since," says he, p. 31., "I was at Wormer, at an inn near the town-hall: the landlady, whose name was Frankjen, told me of the Burgomaster of Hoorn, who in the spring went over the (Zuyder?) sea to buy oxen, and going into a certain house he found seven little children sitting by the fire, each with a porringer in its hand, and eating rice-milk, or pap, with a spoon; on which the Burgomaster said 'Mother, you are very kind to your neighbours, since they leave their children to your care.' 'No,' said the woman, they are all my own children, which I had at one birth; and if you will wait a moment, I will show you more that will surprise you.' She then fetched seven other children a birth older: so she had fourteen children at two births. Then the woman said to the Burgomaster, 'I am now enceinte, and I think in the same way as before: if you come here next year, call upon me again.' And so, the next year, when the Burgomaster went over the sea, he called upon the woman and the woman had again brought forth seven children at a birth. Thus the woman had at three births twenty-one children."

I subjoin the original of which the above is a literal translation.

J. S.Woudenberg, April, 1851.

RAMASSHED, MEANING OF THE TERM

In the curious volume recently edited by Sir Henry Ellis for the Camden Society, entitled The Pilgrymage of Syr R. Guylforde, Knyght, a singular term occurs, which may claim a note of explanation. It is found in the following passage:

"Saterdaye to Suse, Noualassa, and to Lyungborugh; and at the sayd Noualassa we toke moyles to stey us vp the mountayne, and toke also marones to kepe vs frome fallynge. And from the hyght of the mounte down to Lyuyngborugh I was ramasshed, whiche is a right strange thinge."—P. 80.

Sir Henry has not bestowed upon us here any of those erudite annotations, which have customarily enhanced the interest of works edited under his care.

Sir Richard Guylforde was on his homeward course from the Holy Places by way of Pavia, where he visited the convent and church which contained the shrine and relics of St. Augustine, as also the tomb of Lionel, Duke of Clarence, second son of Edward III., whose monumental inscription (not to be found in Sandford's Genealogical History) the worthy knight copied.

On the 13th Feb. 1506, Sir Richard approached the ascent of Mont Cenis by the way of S. Ambrogio and Susa. At the village of Novalese, now in ruins, the party took mules, to aid their ascent, and marroni, long-handled mattocks, or pick-axes, to prevent their falling on the dangerous declivities of the snow. The journey was formerly made with frightful expedition by means of a kind of sledge—an expedient termed la ramasse—which enabled the traveller, previously to the construction of that extraordinary road, well known to most readers, to effect in a few minutes a perilous descent of upwards of 6000 feet. The ramasse, as Cotgrave informs us, was—

"A kind of high sled, or wheelbarrow, whereon travellers are carried downe certaine steep and slippery hils in Piemont."

Its simplest form had probably been a kind of fagot of brushwood,—ramazza, or a besom, not much unlike the rapid locomotive of witches, who were called in old times ramassières, from their supposed practice of riding on a ramée, ramasse, or besom. At the present time even, it occasionally occurs that an adventurous traveller crossing the Mont Cenis is tempted to glide down the rapid descent, in preference to the long course of the zigzag road; and remember to have heard at Lauslebourg the tale, doubtless often related, of an eccentric Milord who ascended the heights thrice from that place, a journey of some hours, for the gratification of the repeated excitement caused by a descent on the ramasse in about as many minutes. The cranium of a horse, as it was stated, was the vehicle often preferred for this curious adventure: and the traveller guided or steadied his course by trailing a long staff, a practice for security well known to the Alpine tourist. This may probably have been the use of the "marones" taken by Sir Richard Guyldeford and his party at Novalese.

The terms, to be "ramasshed," is not, as I believe, wholly disused in France. It was brought to the metropolis with the strange amusement known as the Montagne Russe. In the valuable Complément du Dictionnaire de l'Académie, compiled under the direction of Louis Barré, we find the following phrase:

"Se faire ramasser, se dit aujourd'hui, dans une acception particulière, pour, Se faire lancer dans un char, du haut des élévations artificielles qui se trouvent dans les jardins publics."

Such a disport had been known previously to the expedition to Moscow, and the favourite divertisement à la Russe, so much in vogue amongst the Parisians for a few subsequent years. Roquefort informs us that—

"Ramasse étoit le nom d'un jeu que nous avions apporté des Alpes, où il est encore en usage pendant l'hiver, et principalement en temps de neige."

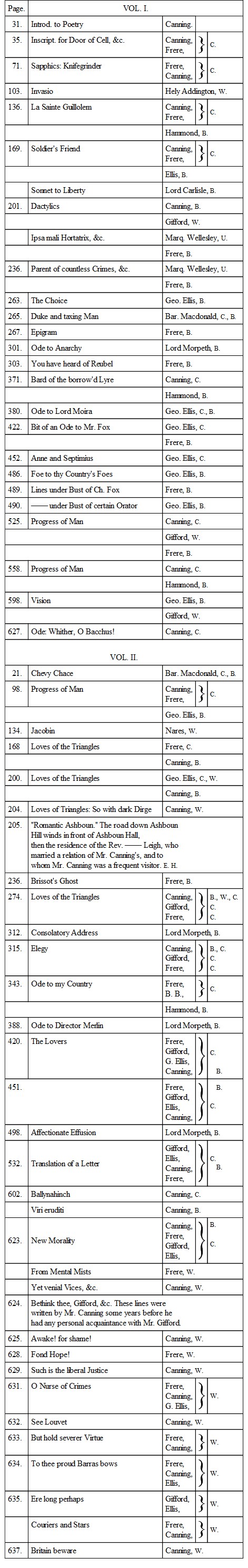

Albert Way.AUTHORS OF THE POETRY OF THE ANTI-JACOBIN

The following notices of the writers of many of the poetical pieces in the Anti-Jacobin may prove interesting to many of your readers. They are derived from the following copies, and each name is authenticated by the initials of the authority upon which each piece is ascribed to particular persons:

C. Canning's own copy of the poetry.

B. Lord Burghersh's copy.

W. Wright the publisher's copy.

U. Information of W. Upcott, amanuensis.

The copy of the Anti-Jacobin to which I refer is the fourth, 1799, 8vo.

Wright, the publisher of the Anti-Jacobin, lived at 169. Piccadilly, and his shop was the general morning resort of the friends of the ministry, as Debrell's was of the oppositionists. About the time when the Anti-Jacobin was contemplated, Owen, who had been the publisher of Burke's pamphlets, failed. The editors of the Anti-Jacobin took his house, paying the rent, taxes, &c., and gave it up to Wright, reserving to themselves the first floor, to which a communication was opened through Wright's house. Being thus enabled to pass to their own rooms through Wright's shop, where their frequent visits did not excite any remarks, they contrived to escape particular observation.

Their meetings were most regular on Sundays, but they not unfrequently met on other days of the week, and in their rooms were chiefly written the poetical portions of the work. What was written was generally left open upon the table, and as others of the party dropped in, hints or suggestions were made; sometimes whole passages were contributed by some of the parties present, and afterwards altered by others, so that it is almost impossible to ascertain the names of the authors. Where, in the above notes, a piece is ascribed to different authors, the conflicting statements may arise from incorrect information, but sometimes they arise from the whole authorship being assigned to one person, when in fact both may have contributed. If we look at the references, vol. ii. pp. 420. 532. 623., we shall see Mr. Canning naming several authors, whereas Lord Burghersh assigns all to one author. Mr. Canning's authority is here more to be relied upon. "New Morality" Mr. Canning assigns generally to the four contributors; Mr. Wright has given some interesting particulars by appropriating to each his peculiar portion.

Gifford was the working editor, and wrote most of the refutations and corrections of the "Lies," "Mistakes," and "Misrepresentations."

The papers on finance were chiefly by Pitt: the first column was frequently for what he might send; but his contributions were uncertain, and generally very late, so that the space reserved for him was sometimes filled up by other matter. He only once met the editors at Wright's.

Upcott, who was at the time assistant in Wright's shop, was employed as amanuensis, to copy out for the printer the various contributions, that the authors' handwriting might not be detected.

Edw. Hawkins.The Anti-Jacobin (Vol. iii., p. 334.).—In a copy of the Poetry of the Anti-Jacobin, now in my possession, occurs this note in the autograph of Mr. James Boswell:—

"These lines [Lines written by Traveller at Czarco-zelo] were written by William PITT—as I learnt from his nephew on the 28th of May 1808, at a dinner held in honour of his memory."

The sirname is in large capital letters; the year is indistinctly written. This is the note which is indicated in the auction-catalogue of the library of Mr. Boswell, No. 2229.

Bolton Corney.Minor Notes

Egg and Arrow Ornament.—Mr. Ruskin, in his Stones of Venice, vol. i. p. 305., says—

"The Greek egg and arrow cornice is a nonsense cornice, very noble in its lines, but utterly absurd in its meaning. Arrows have had nothing to do with eggs (at least since Leda's time), neither are the so-called arrows like arrows, nor the eggs like eggs, nor the honeysuckles like honeysuckles: they are all conventionalized into a monotonous successiveness of nothing—pleasant to the eye, useless to the thought."

The ornament of which Mr. R. thus speaks is indifferently called egg and tongue, egg and dart, as well as egg and arrow. It seems to me that the egg is a complete misnomer, although common to all the designations; and I fancy that the idea of what is so called was originally derived from the full-length shield, and therefore that the ornament should be named the shield and dart, an association more reasonable than is suggested by any of the ordinary appellations. Can any of your correspondents offer any confirmation of this?

B. J.Liverpool, March 31. 1851.

Defoe's Project for purifying the English Language.—Among the many schemes propounded by De Foe, in his Essay upon Projects, published in 1696, there is one which still remains a theory, although eminently practicable, and well worthy of consideration.

He conceived that there might be an academy or society formed for the purpose of correcting, purifying, and establishing the English language, such as had been founded in France under Cardinal Richelieu.

"The work of this society," says Defoe, "should be to encourage polite learning, to polish and refine the English tongue, and advance the so much neglected faculty of correct language; also, to establish purity and propriety of style, and to purge it from all the irregular additions that ignorance and affectation have introduced; and all these innovations of speech, if I may call them such, which some dogmatic writers have the confidence to foster upon their native language, as if their authority were sufficient to make their own fancy legitimate."

Never was such society more needed than in the present day, when you can scarcely take up a newspaper, or a periodical, a new poem, or any modern literary production, without finding some new-coined word, perplexing to the present reader, and a perfect stumbling-block in the way of any future editor.

Some of these words are, I admit, a welcome addition to our common stock, but the greater part of them are mere abortions, having no analogy to any given root.

A society similar to the one proposed by Defoe might soon be established in this country, if a few such efficient authorities as Dr. Kennedy would take the initiative in the movement.

He who should first establish such a society, and bring it to a practicable bearing, would be conferring an inestimable boon on society.

I trust that these hints may serve to arouse the attention of some of the many talented contributors to the "Notes and Queries," and in due season bring forth fruit.

David Stevens.Godalming, April 19. 1851.

Great Fire of London.—Our popular histories of England, generally, contain very indefinite statements respecting the extent of destruction wrought upon the city of London by the Great Fire. I have therefore thought it may be interesting to others, as it has been to myself, to peruse the following, which purports to be "extracted from the Certificates of the Surveyors soon after appointed to survey the Ruins."

"That the fire that began in London upon the second of September, 1666, at one Mr. Farryner's house, a baker in Pudding Lane, between the hours of one and two in the morning, and continued burning until the sixth of that month, did overrun the space of three hundred and seventy-three acres within the walls of the city of London, and sixty-three acres three roods without the walls. There remained seventy-five acres three roods standing within the walls unburnt. Eighty-nine parish churches, besides chappels burnt. Eleven parishes within the walls standing. Houses burnt, Thirteen thousand two hundred.

I copy this from a volume of tracts, printed 1679 to 1681; chiefly "Narratives" of judicial and other proceedings relating to the (so called) "Popish Plots" in the reign of Charles II.

Wm. Franks Mathews.Noble or Workhouse Names—

"The only three noble names in the county were to be found in the great house [workhouse]; mine [Berners] was one, the other two were Devereux and Bohun."—Lavengro, iii. 232.

The above extract reminds me of a list of names of the poor about St. Alban's, which I forwarded some months since, viz. Brax, Brandon, De Amer, De Ayton, Fitzgerald, Fitz John, Gascoigne, Harcourt, Howard, Lacey, Stanley, Ratcliffe.

A. C.Queries

PASSAGES IN THE NEW TESTAMENT ILLUSTRATED FROM DEMOSTHENES

Acts xvii. 21.:

"For all the Athenians and strangers which were there spent their time in nothing else, but either to tell, or to hear some new thing."

Can any of your biblical correspondents inform me in what commentary upon the New Testament the coincidence with the following passages in Demosthenes is noticed, or whether any other source of the historical fact has been recorded? In the translation of Petrus Lagnerius, Franc. 1610 (I have not at hand the entire works), we find these words:

"Nihil est omnium, Athenienses, in præsentiâ nocentius, quam quod vos alienati estis a rebus, et tantisper operam datis, dum audientes sedetis, si quid Novi nuntiatum fuerit" (4. contr. Phil.).

Again:

"Nos vero, dicetur verum, nihil facientes, hic perpetuo sedemus cunctabundi, tum decernentes, tum interrogantes, si quid Novi in foro dicatur."—4 Orat. ad Philipp. Epist.