полная версия

полная версияNotes and Queries, Number 76, April 12, 1851

"Thus far ye narrative of Lindsey himself; but something further is to be remembered to complete & confirm ye story.

"When Mr. Thorowgood saw his friend Lindsey come into his yard, his horse and himself just tired, in a sort of amaze he said, 'How, now, Colonel; we hear there is like to be a battle shortly. What! fled from your colours?' 'A battle!' said ye other; 'yes, there has bin a battle, and I am sure ye King is beaten. If ever I strike a stroke for Cromwell again, may I perish eternally, for I am sure he has made a league with ye Devil, and he will have him in due time.' Then, desiring his protection from Cromwell's inquisitors, he went in & related ye whole story, and all the circumstances, concluding with these remarkable words, That Cromwell w'd certainly die that day seven year that the battle was fought.

"The strangeness of his relation caused Mr. Thorowgood to order his son John, then about 12 years of age, to write it in full length in his common place book, & to take it from Lindsey's own mouth. This common place book, and likewise ye same story writen in other books, I am sure is still preserv'd in ye family of ye Thorowgoods: But how far Lindsey is to be believed, & how far ye story is to be accounted incredible, is left to ye reader's faith and judgment, & not to any determination of our own."

Replies to Minor Queries

Gig Hill (Vol. iii., p. 222.).—Perhaps your correspondent is mistaken in saying that "there is no indication of anything in the land to warrant the name." At least, the very fact of its being a hill is suspicious. If I could venture to affront you with a pun, I should say, that it seems to me very natural that the top of a hill should look like a gig. Mercy on us! do words wear out so fast? Why, I have not reached three-score, and did not I "whip my gig" when I was an "infant"?—not an infant born in a remote province, sucking in archaism with my mother's milk, playing with heirloom toys, and calling them by obsolete names, but a smart little cockney, born and bred in the parish of St. Andrew, Holborn, where, no doubt, there were gig-whipping brats plenty. In the crowded state of your columns, you would not thank me for enlarging on the top-hic, or I should really feel disposed to enter into a dissertation on the nature and characteristic differences of whipping-tops, humming-tops, peg-tops, and gigs. As to the latter, it certainly occurs to me, now that the question is raised, that I have not seen such a thing for a long time; though I fancy gigs lying in the shop-windows, as they did at a period when I was more likely to observe them; and if they have become so far forgotten, it may be worth while, for the sake of Shakspeare, to say that they were generally (as far as I remember always) made of horn; and therefore, when Holofernes says "Go, whip thy gig" (which means just the same as Mr. Oldbuck's "Sew your sampler, monkey!"), Moth replies, "Lend me your horn to make one, and I will whip about your infamy circum circa; a gig of a cuckold's horn!" It is enough to add that the gig was made of the tip of the horn, and looked, while spinning, like an inverted extinguisher. It was hollow, but my impression is that there was sometimes lead at the bottom of the inside. Even with the ballast, it was a ticklish, volatile, kickety thing, much more difficult to set up and to keep up than the sober whipping-top, and bearing somewhat the same relation to one in bulk and motion, that a ship's gig may do to herself, or a gig on land to a coach. As to Gig Hill, however, unless it has a conical top, some other explanation must be sought.

N. B.[C., E. H., and numerous other correspondents, have also kindly replied to this Query.]

Epigram against Burke (Vol. iii., P. 243.).—

"Oft have I heard that ne'er on Irish ground,A poisonous reptile ever yet was found;Nature, though slow, will yet complete her work,She has saved her venom to create a Burke."The author of these lines was Warren Hastings himself; his private secretary (Mr. Evans) sat by his side during the trial, and saw him write the above. My authority is a niece of Mr. Evans, who formed one of her uncle's family at the period of the trial.

N. M.Engraved Portrait (Vol. iii., p. 209.).—This is the portrait of Samuel Clarke, the ejected minister of Bennet Fink, London. I have three impressions of this engraving now before me. Two of these are in an illustrated Granger, and are in different states, the earlier one having no shading in the background. The third copy is prefixed to—

"A Collection of the Lives of Ten Eminent Divines, Famous in their Generations for Learning, Prudence, Piety, and painfuless in the work of the Ministry, &c. By Sa. Clarke, Preacher of the Gospel in St. Bennet Fink, London, 1662." 4to.

Very likely the same plate had been previously used for some other of Clarke's numerous publications. At the end of the verses beneath the portrait, my copies have "P.V.A.M. fecit," which, I suppose, are the initials of Peter Vinke.

John I. Dredge.A full and interesting account of this worthy divine is given in Granger, vol. v. p. 73.; and the quatrain will be found annexed to a brief account of the same portrait in Ames's English Heads, p. 43.

J. F. Y.Salgado's Slaughter-house (Vol. ii., p. 358.).—Your correspondent asks, Who was Salgado? and his question has not yet, I believe, been answered. James Salgado, whose name does not appear in any biographical dictionary, though it deserves to do, and whose pieces are unnoticed in Peck's Catalogue, though they should certainly not have been omitted, was a Spanish priest, who renounced the Roman Catholic belief, and was imprisoned by the Inquisition, and after undergoing many sufferings made his escape to England in the latter part of the reign of Charles II. His history is contained in An Account of his Life and Sufferings, in a 4to. tract in my possession, entitled, A Confession of Faith of James Salgado, a Spaniard, and sometimes a Priest in the Church of Rome, London, 1681, 4to. Watt and Lowndes both notice some of his pieces, but their lists are very imperfect, and do not comprise the tract, of which your correspondent gives the title, and which is also in my possession, and several others which I have noted in my copy of my Confession, but which it is perhaps unnecessary to enumerate here.

James Crossley.Mathew's (not Matthew's) Mediterranean Passage (Vol. iii., p. 240.).—I have a copy of this work, and shall have pleasure in forwarding it to Mercurii for perusal, if he will address a note to me, which the publisher of "Notes and Queries" will forward.

Nibor.Oxford, March 29. 1851.

The Mitre and the "Cloven Tongues" (Vol. iii., p. 146.).—My attention has just been directed to the remark of your correspondent L. M. M. R., who adduces the miracle of the "cloven tongues as of fire" as having supplied the form of the mitre.

This is an old explanation; but your correspondent does not appear to be aware that "cloven" has been rejected by high classical authority, as not being a correct interpretation of the word διαμεριζόμεναι. The exact translation is, "And tongues as of fire appeared, being distributed to them." The same verb is used in the passage, "They parted my garments among them,"—parted or distributed—the exact equivalent.

It appears to me that the translators have here made an extraordinary blunder. They have, I think, mistaken διαμηρίζω for διαμερίζω. For the peculiar meaning of the former verb I beg to refer those who have not observed it, to Liddell and Scott's Lexicon. The substitution of a letter here (η for ε) would give to the Scripture term a significance, which, though analogous to that of the current translation, is immeasurably distant from the exact interpretation.

Hughes Frazer Halle.Chudleigh, March 24. 1851.

Slums (Vol. iii., p. 224.).—This word is, I take it, an Americanism, being an abbreviation of settlements.

The back settlements and back slums are used synonymously.

D. Q."God's Acre" (Vol. ii., p. 56.).—On looking back to some of your old numbers I find W. H. K. has never been answered with regard to the above application of the term to churchyards. Longfellow (Liverpool edition, 1850, p. 36.) commences one of his poems thus:

"I like that ancient Saxon phrase, which callsThe burial-ground God's Acre. It is just;It consecrates each grave within its walls,And breathes a benison o'er the sleeping dust."Whether this may be any help to W. H. K., I know not, but I cannot refrain from the Query—What is the Saxon phrase alluded to?

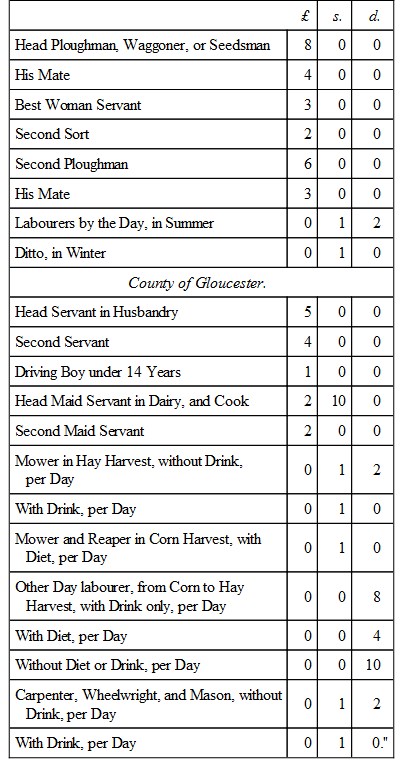

W. H. P.Wages in the last Century (Vol. iii., p. 143.).—I have a note on this subject which is at A. A.'s service, extracted from the Gentleman's Magazine for May 1732, vol. ii p. 771.:—

"Wages (Yearly) appointed by the Justices, A.D. 1732, to be taken by the Servants in the County of Kent.

I send the note as I have it in my commonplace book; but I should think that the periodical from which the above is extracted, contains much that would suit A. A.'s purpose.

E. S. Taylor.Martham, Norfolk.

Tradesmen's Signs (Vol. iii., p. 224.).—The projecting signs over tradesmen's shop-doors were removed under the London Paving Act, 6 Geo. III. c. 26. s. 17. In the Percy History of London, i. 179., the act is erroneously said to have been passed in 1762. From Malcolm's Anecdotes of London, pp. 468, 469., it seems that the clause in question was inserted in the act in consequence of inquiries by a committee appointed by the Court of Common Council in 1764. Mr. Peter Cunningham, in the "London Occurrences" prefixed to his Handbook for London, says: "1766. The house-signs of London taken down."

No doubt the existing Metropolitan Paving Acts contain clauses which will prevent tradesmen from again putting up projecting signs.

C. H. Cooper.Cambridge.

Standfast's Cordial Comforts, &c. (Vol. iii., p. 143.).—Abhba will find in a catalogue of curious books published by G. Bumstead, 205. High Holborn, an early edition of Standfast. It is described thus:

"Standfast (R.), A Little Handful of Cordial Comforts, and a Caveat against Seducers; with the Blind Man's Meditations, and a Dialogue Between a Blind Man and Death, 12mo. 1684."

This may assist Abhba in his researches.

Z.St. Pancras (Vol. ii., p. 496.).—Your correspondent Mr. Yeowell asks where C. J. Smith's collection of MSS., cuttings and prints, &c. relating to the parish of St. Pancras, are deposited? It is in the library of Richard Percival, Esq., 9. Highbury Park, Islington.

Can any of your readers give an account of St. Pancras? He was martyred May 12, 304.

R.[Has our correspondent looked at the Calendar of the Anglican Church, lately published by Parker of Oxford? A brief notice of St. Pancras will be found on p. 274. of that useful little work.]

Lines on "Woman's Will" (Vol. i., p. 247.).—Although somewhat late in the day, I send you the following paragraph from the Examiner of May 31, 1829:

"Woman's Will.—The following lines (says a correspondent of the Brighton Herald) were copied from the pillar erected on the Mount in the Dane-John Field, formerly called the Dungeon Field, Canterbury:

'Where is the man who has the power and skillTo stem the torrents of a woman's will?For if she will, she will, you may depend on't,And if she won't, she won't so there's an end on't."'H. C.Workington.

Scandal against Queen Elizabeth (Vol. ii., p. 393.; Vol. iii., p. 11.).—In Hubback on the Evidence of Succession, p. 253, after some remarks on the word "natural," not of itself in former times denoting illegitimacy, this passage occurs:

"But as early as the time of Elizabeth the word natural, standing alone, had acquired something of its present meaning. The Parliament, in debating upon the act establishing the title to the crown in the Queen's issue, thought it proper to alter the words 'issue lawfully begotten,' into 'natural-born issue,' conceiving the latter to be a more delicate phrase. But this created a suspicion among the people, that the Queen's favourite, Leicester, intended after her death to set up some bastard of his own, pretending it was born of her, and bred up privately."—Duke of Buckingham On Treasons, cited Amos's Fortescue, p. 154.

J. H. L.Coggeshall Job (Vol. iii., p. 167.).—Does J. C. allude to the tradition that the Coggeshall people placed hurdles in the stream to turn the river, and chained up the wheelbarrow when the mad dog bit it?

J. H. L.Whale caught at Greenwich before the Death of Cromwell (Vol. iii., p. 207.).—B. B. wishes a record of the capture of a whale at Greenwich, immediately previous to Cromwell's death. I take leave to inform him that, in a tract entitled A Catalogue of natural Rarities, with great Industry, Cost and thirty Years' Travel in foreign Countries collected, by Robert Hubert, alias Forges, Gent., and sworn Servant to his Majesty. And Dayly to be seen at the Place called the Musick House, at the Miter, near the West End of St. Paul's Church, 1664, there is the following item:—

"The vein of the tongue of that whale that was taken up at Greenwich, a little before Cromwell's death."

W. Pinkerton.Ham.

Fronte Capillatâ, &c. (Vol. iii., pp. 8. 43. 124.).—The following lines from Tasso's Amore Fuggitivo contain the same figure as the Latin quoted above:

"Crespe hà le chiome e d'oro,E in quella guisa appunto,Che Fortuna si pingeHa lunghi e folti in sulla fronte i crini;Ma nuda hà poi la testaAgli opposti confini."Robert Snow.The lines quoted by your correspondent are from Peacock's "Headlong Hall," and are imitated from Machiavelli's "Capitolo dell' Occasione." The whole air stands thus; the second stanza differing slightly from the version given by Mr. Burt. The lines are very pretty, at least in my opinion.

"LOVE AND OPPORTUNITY"Oh! who art thou, so swiftly flying?My name is Love, the child replied;Swifter I pass than south-winds sighing,Or streams through summer vales that glide.And who art thou, his flight pursuing?'Tis cold Neglect whom now you see:The little god you there are viewing,Will die, if once he's touched by me."Oh! who art thou so fast proceeding,Ne'er glancing back thine eyes of flame?Mark'd but by few, through earth I'm speeding,And Opportunity's my name.What form is that which scowls beside thee?Repentance is the form you see:Learn then, the fate may yet betide thee.She seizes them who seize not me."W. R. M.John Sanderson, or the Cushion-dance (Vol. ii., p. 517.).—Though I am unable to answer your correspondent Mac's inquiry as to the antiquity of this dance, it may interest him as well as others of the readers of "Notes and Queries" to know, that when Walpole made up his mind to abandon his Excise bill (which met with a still fiercer opposition out of doors than in the House of Commons), he signified his intention to a party of his adherents at the supper-table, by quoting the first line of the accompanying song:—

"This dance it will no further go!"7This, at least, shows the popularity of this dance in the reign of George II.

H. C.Workington.

George Steevens and William Stevens (Vol. iii, p. 230.).—The late Sir J. A. Park wrote Memoirs of William Stevens, the Treasurer of Queen Anne's Bounty, and the biographer of Jones of Nayland. As little resemblance must have existed between this gentleman and "the Puck of commentators," George Steevens, as between the two Harveys:

"The one invented Sauce for FishThe other Meditations."J. H. M.Memoirs of Stevens by the late Sir James Allan Park have been published, and are well worth reading; but this Stevens was not George Steevens, the Shakespearian commentator, but William, Treasurer of Queen Anne's Bounty, one of the most meek and humble minded of men.

"He was inferior to none in profound knowledge, and steady practice of the doctrines and discipline of the Church of England; austere to himself alone, charitable and indulgent towards others, he attracted the young by the cheerfulness of his temper, and the old by the sanctity of his life."

Miss Bockett should not confound such a holy character with George Steevens.

E. H.Memoirs of George Steevens, Esq., F.R.S. and F.S.A. (Vol. iii., p. 119.).—In answer to A. Z. it may be stated that a brief memoir of Mr. Steevens was given in Nichols's Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century, Vol. ii. p. 680.; further anecdotes, and some of his letters, in vol. v. of Nichols's Literary Illustrations; and further letters (his correspondence with Dr. Percy, Bishop of Dromore), in vol. vii. of the latter work; besides many incidental notices, which will be found by reference to the indexes. On the last occasion a copy of his portrait by Dance, was attached; and in vol. v. of the Literary Illustrations is an engraving of his monument by Flaxman, in Poplar Chapel.

N.Tradescant (Vol. iii., p. 119.).—At what period the elder Tradescant came into England is not with certainty known, but it is supposed to have been about the end of Queen Elizabeth's reign, or the beginning of that of James I. He obtained the title of Royal Gardener circa 1629.

It may not be superfluous to mention (on the authority of Allen's History of Lambeth, p. 142.) that formerly the three following lines were on the monument in Lambeth churchyard, until its reparation by public subscription in 1773, when they were left out:

"This monument was erected at the charge of Hester Tradescant, the relict of John Tradescant, late deceased, who was buried the 25th of April, 1662."

Alfred W. H.Kennington.

Origin of Harlequins (Vol. iii., p. 165.).—Your correspondent and querist E. L. N. wishes for an account of the Origin of Harlequins. I beg to refer E. L. N. to an account of the Hellequines, or "La Mesnie Hellequin," given by M. Paul Paris, in his work on the Manuscripts François de la Bib. du Roi, vol. i. p. 322. M. Paris says:

"On donnoit ce nom (Hellequines) à des espèces de feux follets ou génies plutôt malfaisants que favorables, et plutôt moqueurs que malfaisants.... L'origine de la tradition de la Mesnie Hellequin se perd dans l'obscurité des temps. On l'entendoit surtout bruire dans les environs de la ville d'Arles.... J'ignore la première origine de cette locution; mais ce qui me semble incontestable, c'est qu'on confondit facilement la Mesnie Hellequin avec celle 'de la Mort,' famille bariolée de rouge et de noir, et dont le manteau de cérémonie devoit être un grand pan de toile ou linceul. Déjà le lecteur a devancé la conséquence qu'il faut tirer de tout cela; la Mesnie Hellequin, partie nécessaire des cortéges effrayants ou grotesques dans le moyen-âge, est devenue insensiblement, sous la main des arrangeurs, notre famille d'Arlequin. Le costume bariolé d'Arlequin n'est rien autre que le fantastique costume du représentant de la Mort.... Et, si ce que je viens de dire est fondé, on ne répètera plus après Ménage (Gilles), que le mot Arlequin fut pris d'abord, sur la fin du XVI siècle, par un certain bouffon italien que le Président Harlay avoit accueilli. Il est certain que le mot Arlequin se trouve très-anciennement dans un grand nombre de mystères.

"'Numquid me velis,' ecrivoit Jean Raulin, mort en 1514, 'antiquam illam familiam Harlequini, revocare, ut videatur mortuus inter mundanæ curiæ nebulas et caligines equitare?'"

By the above extracts, which I fear you will find too long, harlequinades would seem rather to be derived from the wanton pranks of sprites than the coarse gambols of buffoons; and this derivation would certainly best agree with the accepted character of the modern harlequin.

H. C. C."Predeceased" and "Designed" (Vol. iii., p. 143.).—The former word is used in an active sense by Shakspeare, in his "Rape of Lucrece:"

"If children predecease progenitors,We are their offspring, and they none of ours.""Designed," in the sense of "designated," is employed by Locke:

"'Tis not enough to make a man a subject, to convince him that there is regal power in the world; but there must be ways of designing and knowing the person to whom the regal power of right belongs."

Cowgill."Quadrijugis invectus equis," &c. (Vol. ii., p. 391.).—These lines, in which "veriis" and "antesolat" are, of course, misprints for "variis" and "antevolat," apply with such peculiar exactness to Guido's celebrated Aurora, at the Rospigliosi Palace, that I cannot but think the painting has given rise to the lines. Besides, in the ancient mythology, the Horæ are said to be three in number, daughters of Jupiter and Themis, and one of their offices was harnessing the horses of the Sun. It is unlikely, therefore, that any classic author would mention them as being seven in number.

C. I. R.St. John's Bridge Fair (Vol. iii., p. 88.).—Perhaps in the county of Northampton, and in the city of Peterborough, where a fair, commencing October 2d, is still called "Bridge Fair." The parish church of Peterborough is dedicated to St. John Baptist; but a fair on the saint's day would be too near the other, and probably more ancient fair, which is held on old St. Peter's Day, to whom the cathedral church is dedicated.

Arun.Anticipations of Modern Ideas by Defoe (Vol. iii., pp. 137. 195.).—It is a singular fact, to which I do not remember a reference has hitherto been made, that Defoe, in his Life and Adventures of Captain Singleton, has foreshadowed the discovery by recent travellers of a great inland lake in the South of Africa. He describes his adventurous hero and companions, during their attempt to cross this vast continent from Mozambique to Angola, as having, on the ninth day of their journey, come in "view of a great lake of water."

"The next day," he adds, "which was the tenth from our setting out, we came to the edge of this lake, and happily for us, we came to it at the south point of it, for to the north we could see no end of it; so we passed by it, and travelled three days by the side of it."—Life, Adventures, and Piracies of Captain Singleton, chap. vi.

According to a rough calculation by one of the party, they were, a few days before reaching it, 700 miles from the coast of Mozambique, and 1500 from the Cape of Good Hope. Now Messrs. Murray and Oswell, the enterprising travellers to whom we owe the discovery of this vast South African lake, describe it as being in longitude 24° East, latitude 19° South; a position not very wide apart from that indicated in Defoe's amusing fiction.

T. C. Smith.Lord Howard of Effingham (Vol. iii., p. 244.).—I submit that the passages quoted by your correspondent are not sufficient evidence to lead us to conclude that that nobleman ever was a Protestant. As to the "neglect of reverence to the Holy Sacrament," it is only said that the priests might pretend that as a cause; and it is not to be supposed that an ambassador would so far forget himself as to show any disrespect to the religion of the prince he was sent to. Besides, it is likely that Lord Howard was chosen for the embassy as being a Catholic, and therefore more acceptable to a prince of the same religion.

2nd. Fuller's words only refer to testimony on a disputed fact, on which Catholic evidence the effect quoted by him would have peculiar weight.

3rd. The words to Garnet, who had declared his innocence and abhorrence of the imputed crime, are such as a Catholic would be most likely to use.

4th. The word "our," in the royal instructions, is the word of form, and resembles the editorial "we." In royal instructions to Mr. Shiel at Florence, Mr. Wyse at Naples, or Mr. More O'Ferrall at Malta, her Majesty would use the words "our religion;" would that imply that any or all of those gentlemen were Protestants?

After all, Lord Howard may have conformed to the court religion after the period of the Armada: occasional conformity was frequent at the period.