полная версия

полная версияThe Reckoning

Being an officer, the poor, heavy-witted folk looked to me for the counsel and wisdom my inexperience lacked. All I could do for them was to arrange their retreat to the tavern at the first signal of danger, and to urge that the women and children sleep there at night. My advice was only partly followed. As the golden October days passed, with no fresh alarm from the Sacandaga, their apathetic fatalism turned to a timid confidence that their homes and lands might yet be spared.

Wemple sold his buckwheat on promise of pay in paper dollars, and we milled it and barreled it, and made a deposit in Klein's sugar-bush.

Distant neighbors came a-horseback to the mill with news from neighbors, still more distant, that Sir John had retreated northward from the Sacandaga, toward Edward; that the Tories threatened Ballston; that Indians had been seen near Galway; that the garrison at Schenectady had been warned to take the field against St. Leger; that on Champlain General Haldimand had gathered a great fleet, and his maneuvers were a mystery to the scouts watching him. But no rumors were carried to us concerning Ross and Butler, except that strange vessels had been seen leaving Bucks Island.

The tension, the wearing anxiety, and harrowing chagrin that I had been left here forgotten, waxed to a fever that drove me all day restlessly from field to field, from house to barn, and back to the tavern, to sit watching the road for sign of a messenger to set me free of this dreary, hopeless place.

And on one bright, cold morning in late October, when to keep warm one must seek the sunny lee of the tavern, I sat brooding, watching the crimson maple-leaves falling from the forest in showers. Frost had come, silvering the stiffened earth, and patches of it still lingered in shady places. Oaks were brown, elms yellow; birches had shed their leaves; and already the forest stretched bluish and misty, set with flecks of scarlet maple and the darker patches of the pine.

On that early morning, just after sunrise, I sensed a hint of snow in the wind that blew out of the purple north; and the premonition sickened me, for it meant the campaign ended.

In an ugly and sullen mood I sat glowering at the blackened weeds cut by the frost, when, hearing the sound of horses' feet on the hill, I rose and stood on tiptoe to see who might be coming at such a pace.

People ran out to the rear to look; nearer and nearer came the dull, battering gallop, then a rider rushed into view, leaning far forward, waving his arm; and a far cry sounded: "Express, ho! News for Captain Renault!"

An express! I sprang to the edge of the road as the horse thundered by; and the red-faced rider, plastered with mud, twisted in his saddle and hurled a packet at me, shouting: "Butler is in the Valley! Turn out! Turn out!" sweeping past in a whirlwind of dust and flying stones.

As I caught up the packet from the grass Farris ran out and fired his musket, then set the conch-horn to his mouth and sent a long-drawn, melancholy warning booming through the forest.

"Close up those shutters!" I said, "and fill the water-casks!"

Men came running from barn and mill, shouting for the women and children; men ran to the hill to look for signs of the enemy, to drive in cattle, to close and latch the doors of their wretched dwellings, as though bolt and bar could keep out the red fury now at last unloosened.

I saw a woman, to whose ragged skirts three children clung, toiling across a stump-field, staggering under a flour-sack full of humble household goods. One of the babies carried a gray kitten clasped to her breast.

Pell-mell into the tavern they hurried, white-faced, panting, pushing their terrified children into dark corners and under tables.

"Tell that woman to let her cow go!" I shouted, as a frightened heifer dashed up the road, followed by its owner, jerked almost off her feet by the tether-rope. Old Wemple seized the distracted woman by the shoulder and dragged her back to the tavern, she weeping and turning her head at every step.

In the midst of this howling hubbub I ripped open my despatches and read:

"Johnstown,October 25, 1781."Capt. Renault:

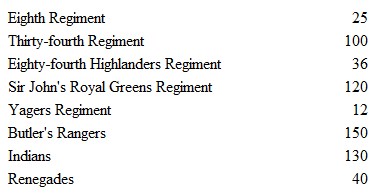

"Sir—Pursuant to urgent orders this instant arrived by express from Col. Willett at Fort Rensselaer, I have the honor to inform you that Major Ross and Capt. Walter Butler have unexpectedly struck the Valley at Warren's Bush with the following forces:

With bat-horses, baggage-wagons, and camp-trains, including forces amounting to a thousand rifles.

"What portion of the invading army this flying column may represent is at present unknown to me.

"The militia call is out; expresses are riding the county to warn every post, settlement, and blockhouse; Colonel Willett, with part of the garrison at Fort Rensselaer, is marching on Fort Hunter to join his forces with your Rangers, picking up the scouts on his way, and expects to strike Butler at the ford below Tribes Hill.

"You will gather from this, sir, that Johnstown is gravely menaced, and no garrison left except a few militia. Indeed, our situation must shortly be deplorable if Colonel Willett does not deliver battle at the ford.

"Therefore, if you can start at once and pick up a post of your riflemen at Broadalbin Bush, it may help us to hold the jail here until some aid arrives from Colonel Willett.

"The town is panic-stricken. All last night the people stood on the lawn by Johnson Hall and watched the red glare in the sky where the enemy were burning the Valley. Massacre, the torch, and hatchet seem already at our thresholds. However, the event remains with God. I shall hold the jail to the last.

"Your ob't serv't,

"Rowley, Major Com'nd'g."For one dreadful moment every drop of blood seemed to leave my body. I sank into a chair, staring into the sunshine, seeing nothing. Then the pale face of Elsin Grey took shape before me, gazing at me sorrowfully; and I sprang up, shuddering, and looking about me. What in God's name was I to do? Go to her and leave these women and babies?—leave these dull-witted men to defend themselves? Why not? Every nerve in me tightened with terror at her danger, every heart-beat responded passionately to the appeal. Yet how could I go, with these white-faced women watching me in helpless confidence; with these frightened children gathering around me, looking up into my face, reaching trustfully for my clenched hands?

In an agony of indecision I turned to the door and gazed down the road, an instant only, then leaped back and slammed the great oaken portal, shooting the bars.

Destiny had decided; Fate had cut the knot!

"Every man to a loop!" I called out steadily. "Wemple, take your sons to the east room; Klein, you and Farris and Klock take the west and south; Warren, look out for the west. They may try to fire the wooden water-leader. Mrs. Farris, see that the tubs of water are ready; and you, Mrs. Warren, take the women and children to the cellar and be ready to dip up buckets of water from the cistern."

Silence; a trample on the stairs as the men ran to their posts; not a cry, not a whimper from the children.

I climbed the stairs, and lying at full length beside the loop, cocked my rifle, and peered out. Almost instantly I saw a man dodge into Klein's house too quickly for me to fire. Presently the interior of the house reddened behind the windows; a thin haze of smoke appeared as by magic, hanging like a curtain above the roof. Then, with a crackling roar that came plainly to my ears, the barn behind the house was buried in flame, seeming almost to blow up in one huge puff of bluish-white smoke.

I heard Wemple's ancient firelock explode, followed by the crack of his sons' rifles, and I saw an Indian running across the pasture.

Klein's house was now curtained with blackish smoke; Wemple's, too, had begun to burn, the roof all tufted with clear little flames, that seemed to give out no smoke in the sunshine. An Indian darted across the door-yard, and leaped into the road, but at the stunning report of Warren's rifle he stopped, dropping his gun, and slowly sank, face downward, in the dust.

Then I heard the barking scalp-yelp break out, and a storm of bullets struck the tavern, leaving along the forest's edge a low wall of brown vapor, which lingered as though glued to the herbage; and through it, red as candle-flames in fog, the spirting flicker of the rifles played, and the old tavern rang with leaden hail. Suddenly the fusillade ceased. Far away I heard a ranger's whistle calling, calling persistently.

Wemple's barn was now burning fiercely; the mill, too, had caught fire, and an ominous ruddy glare behind Warren's windows brightened and brightened.

Behind me, and on either side of me, the frenzied farmers were firing, maddened by the sight of the destruction, until I was obliged to run among the men and shake them, warning them to spare their powder until there was something besides the forest to shoot at. The interior of the tavern was thick with powder-smoke. I heard people coughing all around me.

And now, out of rifle-range, I caught my first good view of the marauders passing along the red stubble-fields north of Warren's barn—some hundred Indians and Tories, marching in columns of fours, rifles atrail, south by east. To my astonishment, instead of facing, they swung around us on a dog-trot, still out of range, pressing steadily forward across the rising ground. Then suddenly I comprehended. They cared nothing for Oswaya when there was prime killing and plunder a-plenty to be had in the Valley. They were headed for Johnstown, where the vultures were already gathering.

Old Wemple had run down-stairs and flung open the door to watch them. I followed, rifle in hand, and we sped hotfoot across the stump-lot and out upon the hill. Surely enough, there they were in the distance, hastening away to the southward at a long, swinging lope, like a pack of timber-wolves jogging to a kill.

"Hold the tavern to-night and then strike out for Saratoga with all your people," I said hurriedly. "They're gone, and I mean to follow them."

"Be ye goin', sir?" quavered the old man. He turned to gaze at the blazing settlement below, tears running down his cheeks.

"Oh, Lord! Thy will be done—I guess," he said.

Farris, Warren, and Klock came up on the run. I pointed at the distant forest, into which the column was disappearing.

"Keep the tavern to-night," I said hoarsely; "there may be a skulking scalp-hunter or two prowling about until morning, but they'll be gone by sunrise. Good-by, lads!"

One by one they extended their powder-blackened, labor-torn hands, then turned away in silence toward the conflagration below, to face winter in the wilderness without a roof.

Rifle at trail, teeth set, I descended the hill, dodging among the blackened stumps, and entered the woods on a steady run. I had no need of a path save for comfort in the going, for this region was perfectly familiar to me from the Sacandaga to the Kennyetto, and from Mayfield Creek to the Cayadutta—familiar as Broadway, from the Battery to Vauxhall. No Indian knew it better, nor could journey by short cuts faster than could I. For this was my own country, and I trusted it. The distance was five good miles to the now-abandoned settlement of Broadalbin, or Fonda's Bush, which some still call it, and my road lay south, straight as the bee flies, after I had once crossed the trail of the Oswaya raiders.

I crossed it where I expected to, in a soft and marshy glade, unblackened by the frost, where blue flowers tufted the swale, and a clear spring soaked the moss and trickled into a little stream which, I remembered, was ever swarming with tiny troutlings. Here I found the print of Cayuga and Mohawk moccasins and white man's boots a-plenty; and, for one fierce instant, burned to pick up the raw trail, hanging on their rear to drive one righteous bullet into them when chance gave me an opportunity. But the impulse fled as it came. Sick at heart I pressed forward once more, going at a steady wolf-trot; and so silently, so noiselessly, that twice I routed deer from their hemlock beds, and once came plump on a tree-cat that puffed up into fury and backed off spitting and growling, eyes like green flames, and every hair on end.

Tree after tree I passed, familiar to me in happier years—here an oak from which, a hundred yards due west, one might find sulphur water—there a pine, marking a clean mile from the Kennyetto at its nearest curve, yonder a birch-bordered gulley, haunted of partridge and woodcock—all these I noted, scarcely seeing them at all, and plodded on and on until, far away through the trees, I heard the Kennyetto roaring in its gorge, like the wind at Adriutha.

A stump-field, sadly overgrown with choke-cherry, sumach, and rabbit-brier, warned me that I was within rifle-hail of the Rangers' post at Broadalbin. I swung to the west, then south, then west again, passing the ruins of the little settlement—a charred beam here, an empty cellar there, yonder a broken well-sweep, until I came to the ridge above the swamp, where I must turn east and ford the stream, under the rifles of the post.

There stood the chimney of what had once been my father's house—the new one, "burned by mistake," ere it had been completed.

I gave it one sullen glance; looked around me, saw but heaps of brick, mortar, and ashes, where barns, smoke-houses, granaries, and stables had stood. The cellar of my old home was almost choked with weeds; slender young saplings had already sprouted among the foundation-stones.

Passing the orchard, I saw the trees under which I had played as a child, now all shaggy and unpruned, tufted thick with suckers, and ringed with heaps of small rotting apples, lying in the grass as they had fallen. With a whirring, thunderous roar, a brood of crested grouse rose from the orchard as I ran on, startling me, almost unnerving me. The next moment I was at the shallow water's edge, shouting across at a blockhouse of logs; and a Ranger rose up and waved his furry cap at me, beckoning me to cross, and calling to me by name.

"Is that you, Dave Elerson?" I shouted.

"Yes, sir. Is there bad news?"

"Butler is in the Valley!" I answered, and waded into the cold, brown current, ankle-deep in golden bottom-sands. Breathless, dripping thrums trailing streams of water after me, I toiled up the bank and stood panting, leaning against the log hut.

"Where is the post?" I breathed.

"Out, sir, since last night."

"Which way?" I groaned.

"Johnstown way, Mr. Renault. The Weasel, Tim Murphy, and Nick Stoner was a-smellin' after moccasin-prints on the Mayfield trail. About sunup they made smoke-signals at me that they was movin' Kingsboro way on a raw trail."

He brought me his tin cup full of rum and water. I drank a small portion of it, then rinsed throat and mouth, still standing.

"Butler and Ross, with a thousand rifles and baggage-wagons, are making for the Tribes Hill ford," I said. "A hundred Cayugas, Mohawks, and Tories burned Oswaya just after sunrise, and are this moment pushing on to Johnstown. We've got to get there before them, Elerson."

"Yes, sir," he said simply, glancing at the flint in his rifle.

"Is there any chance of our picking up the scout?"

"If we don't, it's a dead scout for sure," he returned gravely. "Tim Murphy wasn't lookin' for scalpin' parties from the north."

I handed him his cup, tightened belt and breast-straps, trailed rifle, and struck the trail at a jog; and behind me trotted David Elerson, famed in ballad and story, which he could not read—nor could Tim Murphy, either, for that matter, whose learning lay in things unwritten, and whose eloquence flashed from the steel lips of a rifle that never spoke in vain.

Like ice-chilled wine the sweet, keen mountain air blew in our faces, filtering throat and nostrils as we moved; the rain that the frost had promised was still far away—perhaps not rain at all, but snow.

On we pressed, first breath gone, second breath steady; and only for the sickening foreboding that almost unnerved me when I thought of Elsin, I should not have suffered from the strain.

Somewhere to the west, hastening on parallel to our path, was strung out that pack of raiding bloodhounds; farther south, perhaps at this very instant entering Johnstown, moved the marauders from the north. A groan burst from my dry lips.

Slowing to a walk we began to climb, shoulder to shoulder, ascending the dry bed of a torrent fairly alive with partridges.

"Winter's comin' almighty fast; them birds is a-packin' and a-buddin' already. Down to the Bush I see them peckin' the windfall apples in your old orchard."

I scarcely heard him, but, as he calmly gossiped on, hour after hour, a feeling of dull surprise grew in me that at such a time a man could note and discuss such trifles. Ah, but he had no sweetheart there in the threatened town, menaced by death in its most dreadful shape.

"Are the women in the jail?" I asked, my voice broken by spasmodic breathing as we toiled onward.

"I guess they are, sir—leastways Jack Mount was detailed there to handle the milishy." And, after a pause, gravely and gently: "Is your lady there, sir?"

"Yes—God help her!"

He said nothing; there was nothing of comfort for any man to say. I looked up at the sun.

"It's close to noontide, sir," said Elerson. "We'll make Johnstown within the half-hour. Shall we swing round by the Hall and keep cover, or chance it by the road to Jimmy Burke's?"

"What about the scout?" I asked miserably.

He shook his head, and over his solemn eyes a shadow passed.

"Mayhap," he muttered, "Tim Murphy's luck will hold, sir. He's been fired at by a hundred of their best marksmen; he's been in every bloody scrape, assault, ambush, retreat, 'twixt Edward and Cherry Valley, and never a single bullet-scratch. We may find him in Johnstown yet."

He swerved to the right: "With your leave, Captain Renault, we'll fringe the timber here. Look, sir! Yonder stands the Hall against the sky!"

We were in Johnstown. There, across Sir William's tree-bordered pastures and rolling stubble-fields, stood the baronial hall. Sunlight sparkled on the windows. I saw the lilacs, the bare-limbed locusts, the orchards, still brilliant with scarlet and yellow fruit, the long stone wall and hedge fence, the lawns intensely green.

"It is deserted," I said in a low voice.

"Hark!" breathed Elerson, ear to the wind. After a moment I heard a deadened report from the direction of the village, then another and another; and, spite of the adverse breeze, a quavering, gentle, sustained sound, scarce more than a vibration, that hung persistently in the air.

"By God!" gasped Elerson, "it's the bell at the jail! The enemy are here! Pull foot, sir! Our time has come!"

Down the slope we ran, headed straight for the village. Gunshots now sounded distinctly from the direction of the Court-House; and around us, throughout the whole country, guns popped at intervals, sometimes a single distant report, then a quick succession of shots, like hunters shooting partridges; but we heard as yet no volley-firing.

"Tories and scalpers harrying the outlying farms," breathed Elerson. "Look sharp, sir! We're close to the village, and it's full o' Tories."

Right ahead of us stood a white house; and, as we crossed the hay-field behind it, a man came to the back door, leveled a musket, and deliberately shot at us. Instantly, and before he could spring back, Elerson threw up his rifle and fired, knocking the man headlong through the doorway.

"The impudent son of a slut!" he muttered to himself, coolly reloading. "Count one more Tory in hell, Davy, lad!"

Priming, his restless eyes searched the road-hedge ahead, then, ready once more, we broke into a trot, scrambled through the fence, and started down the road, which had already become a village street. It was fairly swarming with men running and dodging about.

The first thing I saw clearly was a dead woman lying across a horse-block. Then I saw a constable named Hugh McMonts running down the street, chased closely by two Indians and a soldier wearing a green uniform. They caught him as we fired, and murdered him in a doorway with hatchet and gun-stock, spattering everything with the poor wretch's brains.

Our impulsive and useless shots had instantly drawn the fire of three red-coated soldiers; and, as the big bullets whistled around us, Elerson grasped my arm, pulled me back, and darted behind a barn. Through a garden we ran, not stopping to load, through another barnyard, scattering the chickens into frantic flight, then out along a stony way, our ears ringing with the harsh din of the jail bell.

"There's the jail; run for it!" panted Elerson, as we came in sight of the solid stone structure, rising behind its palisades on the high ground.

I sprang across the road and up the slope, battering at the barricaded palings with my rifle-stock, while Elerson ran around the defenses bawling for admittance.

"Hurry, Elerson!" I cried, hammering madly for entrance; "here come the enemy's baggage-wagons up the street!"

"Jack Mount! Jack Mount! Let us in, ye crazy loon!" shouted Elerson.

Somebody began to unbolt the heavy slab gate; it creaked and swung just wide enough for a man to squeeze through. I shoved Elerson inside and followed, pushing into a mob of scared militia and panic-stricken citizens toward a huge buckskinned figure at a stockade loophole on the left.

"Jack Mount!" I called, "where are the women? Are they safe?"

He looked around at me, nodded in a dazed and hesitating manner, then wheeled quick as a flash, and fired through the slit in the logs.

I crawled up to the epaulment and peered down into the dusty street. It was choked with the enemy's baggage-wagons, now thrown into terrible confusion by the shot from Mount's rifle. Horses reared, backed, swerved, swung around, and broke into a terrified gallop; teamsters swore and lashed at their maddened animals, and some batmen, carrying a dead or wounded teamster, flung their limp burden into a wagon, and, seizing the horses' bits, urged them up the hill in a torrent of dust.

I fumbled for my ranger's whistle, set it to my lips, and blew the "Cease firing!"

"Let them alone!" I shouted angrily at Mount. "Have you no better work than to waste powder on a parcel of frightened clodhoppers? Send those militiamen to their posts! Two to a loop, yonder! Lively, lads; and see that you fire at nothing except Indians and soldiers. Jack, come up here!"

The big rifleman mounted the ladder and leaped to the rifle-platform, which quivered beneath his weight.

"I thought I'd best sting them once," he muttered. "Their main force has circled the town westward toward the Hall. Lord, sir, it was a bad surprise they gave us, for we understood that Willett held them at Tribes Hill!"

I caught his arm in a grip of iron, striving to speak, shaking him to silence.

"Where—where is Miss Grey?" I said hoarsely. "You say the women are safe, do you not?"

"Mr. Renault—sir—" he stammered, "I have just arrived at the jail—I have not seen your wife."

My hand fell from his arm; his appalled face whitened.

"Last night, sir," he muttered, "she was at the Hall, watching the flames in the sky where Butler was burning the Valley. I saw her there in a crowd of townsfolk, women, children—the whole town was on the lawn there–"

He wiped his clammy face and moistened his lips; above us, in the wooden tower, the clamor of the bell never ceased.

"She spoke to me, asking for news of you. I—I had no news of you to tell her. Then an officer—Captain Little—fell a-bawling for the Rangers to fall in, and Billy Laird, Jack Shew, Sammons, and me—we had to go. So I fell in, sir; and the last I saw she was standing there and looking at the reddening sky–"

Blindly, almost staggering, I pushed past him, stumbling down the ladder, across the yard, and into the lower corridor of the jail. There were women a-plenty there; some clung to my arm, imploring news; some called out to me, asking for husband or son. I looked blankly into face after face, all strangers; I mounted the stairs, pressing through the trembling throng, searching every whitewashed corridor, every room; then to the cellar, where the frightened children huddled, then out again, breaking into a run, hastening from blockhouse to blockhouse, the iron voice of the bell maddening me!