полная версия

полная версияRollo in Geneva

Rollo asked the concierge what they were.

"Ah," said he, "those are models of a favorite horse and a favorite lamb that belonged to Monsieur Necker. When they died he was very sorry; and he had these models of them made, to perpetuate the memory of them."

After this, in other rooms, the party were shown the table at which Madame de Stael sat in writing Corinne, and the inkstand that she used; and when they went down stairs, the concierge showed them into a large hall, which was situated directly below the rooms they had been visiting, where he said Madame de Stael used to have her dramas performed from time to time before an audience of friends and visitors from the neighborhood.

At length the concierge conducted the party to the door where they had come in. There Mr. Holiday, after giving him a franc, thanked him for his politeness, and bade him good bye. The party took a little walk in the garden, and then returned to the carriage and rode away.

The bodies of Monsieur Necker and of his daughter lie buried in a little grove of trees near the house. The party saw the grove, but visitors are not allowed to go to the graves.

On leaving the chateau, the carriage turned off from the lake, and took a road that led back more into the interior.

"What are we going to see next, father?" said Rollo.

"We are going to see the house where the famous philosopher, Voltaire, lived," replied Mr. Holiday; "though on the way we are going to see a fountain and cascade."

"Is there any thing very remarkable about the fountain?" asked Rollo.

"I don't know," said Mr. Holiday; "only it is mentioned in the guide books as worth being visited."

So the carriage drove on through a very beautiful country, with fields, and gardens, and country seats, and ancient chateaux bordering the way. From time to time, Rollo, on looking back, obtained splendid views of the lake behind him, and of the gently-sloping and highly-cultivated shore on the opposite side, with the snowy range of the Alps beyond, shining in the sun.

At length they arrived at a village, and stopped before an inn. The postilion said that they were to stop there with the carriage, and go to the fountain on foot.

"I will call some one to show you the way," said he.

So he went to one of the houses across the street, and called a woman of the village, and she said that she would go to the school and call her boy.

"But it is a pity," said Mr. Holiday, "to take the boy away from his school."

"O, no," said the woman; "that is nothing at all."

So she ran along the street of the village until she came to the school house, and presently she returned with the boy. He had a book in his hand. Rollo looked at the book, and found that it was a grammar. The covers of it were worn, and the leaves tumbled, and the beginning and end of it were filled with names scribbled on the blank pages, and rude drawings, which made it look exactly like the school books of idle boys, as Rollo had often seen them in America.

Rollo gave back the book to the boy, and the boy gave it to his mother, and then he began walking along the road, to show the party the way to the fountain.

He led them out of the village, and along the pleasant road, until at length they came to a place where there was an open gateway, through which they could see the beautiful grounds of a large country house, which appeared like a hotel. There were ladies and gentlemen walking about the grounds, along the margin of a large stream of water, or sitting in groups under the trees.

"What place is that?" said Rollo to the boy.

"It is a place of baths," said the boy.

Rollo wished to go in there and see the grounds; but the boy walked on, and so Rollo followed him. After a time the guide turned off into a field, and there took a path which led down toward a wood, where they could hear water running. When they came into the wood they saw the water. It was a large stream, large enough for a mill stream, and it ran foaming and tumbling down over its rocky bed in a very picturesque manner.

The walk led along the bank of the stream, under the trees. It was a wide and very pleasant walk, and was well gravelled. Here and there there were little seats, too, at pretty places formed by the windings of the glen.

After walking along a little way, and not coming to any thing more, Mrs. Holiday began to be tired.

"I wonder," said she, "if there is any thing remarkable to see at the end of this path."

"I'll ask the boy," said Rollo.

"Boy," he added, speaking to the little guide, "what is there to see up here?"

"It is this," said the boy, pointing to the brook.

"Isn't there any thing else besides this stream?" asked Rollo.

"No," said the boy.

"He says there is not any thing else," said Rollo to his mother; "and so I don't believe it is worth while to go any farther. We have seen this brook enough, and you will get very tired."

Mrs. Holiday sat down upon a green bench that happened to be near, at a turn of the stream, in order to take time to consider the question.

Mr. Holiday sat down beside her.

"We will wait here, Rollo, while you go on with the boy, and see what you can find. I think there must be something or other remarkable, for they would not make so good a path as this to lead to nothing at all. You may go on with the boy, and see what it comes to, and then you can come back and tell us."

Rollo liked this plan very much, and so he and the boy walked on.

In about five minutes Mr. Holiday heard Rollo calling to him.

"Fa-ther! FA-THER!" said he.

"Well," said Mr. Holiday, "I hear."

"Come up here," said Rollo, calling out again. "It is a very curious place indeed."

So Mr. and Mrs. Holiday rose, and after following the path a short distance farther through the wood, they came to where Rollo was. They found, to their astonishment, that there the brook which they had been following so long came to a sudden end, or rather to a sudden beginning; for the whole volume of water that composed it was seen here to come boiling up out of the ground in a sort of shallow basin, which was formed on the hill side at the head of the glen.

The place was very secluded, but it was very beautiful. It was shaded with trees, which overhung the paths, and the basin, and the various channels of water which flowed from it and around it. The water boiled up very copiously from between the stones that had been set up to form the margin of the basin, and also among the sands which formed the bottom of it. The walk was conducted all around this singular fountain; and it passed across the outlet, where the stream flowed away from it, over a neat little stone dike, which formed the edge of the basin on the lower side.

Rollo led the way to the middle of this dike, and his father and mother followed. They stood there for some time, looking down into the basin to see the water boil up from between the stones and among the sands.

"This is a very curious place indeed," said Mrs. Holiday.

"It certainly is," said Mr. Holiday.

"Well, father," said Rollo, after gazing for some time into the bubbling and boiling fountain, "where does all this water come from? What makes it come up out of the ground?"

"Why, the truth is," said Mr. Holiday, "though it seems to come up, it really comes down.

"Do you see all this mountain up here?" he added. So saying he pointed to the land which seemed to rise to a great height above the head of the glen.

"Yes, sir," said Rollo.

"Well, this mountain," continued Mr. Holiday, "is full of water. All mountains are full of water, for it rains on the summits and sides of them almost continually, and this keeps them always full. Generally this water drains off down into the valleys, through the beds of sand and gravel that lie in the heart of the mountain, and so is not particularly observed. Sometimes it breaks out in small springs, at various places on the mountain sides; and sometimes the shape of the rocks and openings in the mountain are such as to collect a great quantity of it in one place, where it breaks out into the open ground altogether, as it does here. There are a great many such fountains in Switzerland."

"Are there any larger than this?" asked Rollo.

"Yes," said Mr. Holiday, "ten times as large. Sometimes the water forms quite a little river almost immediately after it comes out of the ground."

"I should like to see them," said Rollo.

"Very likely you will see some of them," said his father.

"But then, father," said Rollo, "if this water all comes from the rain, I should think that when it stops raining on the mountain above, then or soon afterwards the water would stop boiling up here."

"No," said his father; "the mountain is so large, and the immense beds of sand, gravel, and rock which it contains hold so much water, that before all that has fallen in one rain has time to get drained away, another rain comes, and so there is a perpetual supply, especially for such fountains as come from channels that reach far into the mountain."

After rambling about this spot for some time, the party returned down the path; but instead of going back into the road again by the way they came, the boy led them through a gate into the grounds of the hotel which they had seen in coming.

The grounds were very beautiful, being shaded with trees, and full of walks; and the stream which came down the glen spread itself out in various directions all over them, filling a great number of channels and basins which had been opened here and there, and were seen in every direction among the trees and foliage. The water flowed very swiftly along from one of these basins to another, sometimes in a continuous torrent, and sometimes by a series of cascades and waterfalls; and in the bottoms of all the little ponds the water was seen boiling up in the clean gray sand, just as it had done in the fountain up the glen.

There were walks every where along the banks of these streams, and little bridges leading across them. There were seats, too, and bowers, and a great many other pretty places. At one spot under a tree was a large white swan, or rather a sculptured image of one, sitting on a marble stone, and pouring out a constant stream of clear cold water from his mouth. Underneath, on a little marble slab, was a tumbler, placed there to enable people to take a drink. Rollo stopped to take a drink; but instead of using the tumbler, he caught the water in a drinking cup which he had bought in Scotland, and which he always carried in his pocket.

After rambling about these grounds for some time, the party went back through the yard of the hotel to the village. There they dismissed the boy. Mr. Holiday gave him half a franc for guiding them. Then they got into their carriage again, and rode on.

In about an hour they came to a little village named Ferney, near which was the chateau that was formerly the residence of the celebrated philosopher Voltaire. The carriage stopped under some ancient trees, and Mr. and Mrs. Holiday and Rollo got out and walked up an avenue. At the head of the avenue they came to a gate which led into the grounds of the chateau.

There was a bell cord hanging by this gate, and a placard up, requesting visitors to ring the bell, and not to enter the grounds until the domestic should come to guide them.

"Shall I ring, father?" said Rollo.

"Yes," said Mr. Holiday; "ring away."

So Rollo pulled the bell rope, and very soon a domestic came. He received the company very politely, and invited them to follow him.

Mr. and Mrs. Holiday and Rollo accordingly followed him into the yard. The domestic led them round to the front of the house, which was turned away from the road. The front faced a beautiful lawn, ornamented with walks and trees. In one place there was a table under the trees, with seats around it, as if the family were accustomed sometimes to take their tea there. From this lawn there was a beautiful view of the lake and of the mountains beyond.

The domestic led them into the house, and showed them the two rooms in it which contained most of the memorials of Voltaire. The most remarkable of these memorials was a marble monument which stood on one side of the room, and which Rollo said looked like an ornamental stove, that contained Voltaire's heart. His body was buried in Paris, but his heart was deposited in this sepulchral urn.

Besides this there were a number of pictures in the room, which had been placed there by Voltaire. Some of them had been given to him by the emperors and kings that he had been acquainted with.

Rollo, however, did not take much interest in any of these things. The singular appearance of the room and of the furniture interested him in some degree by its novelty, but in other respects he was very little amused by what he saw. He was glad when the visit to the house was over, and he came out again upon the lawn.

From the lawn there was a very splendid view. There was a broad and very fertile slope of land extending for several miles down to the shore of the lake. Beyond it was seen the blue expanse of the water, and still farther another magnificent slope of fertile and richly-cultivated land, which extended back beyond the lake to the foot of the mountains. A lofty range of snow-clad summits rose in the distance, the towering summit of Mont Blanc reposing like a monarch in the midst of them.

There was a curious covered walk along on one side of this lawn. It was a walk covered with foliage. It was walled in on the sides, too, as well as covered above with the foliage. Two hedges had been planted, one on each side; and as they had grown, the leaves and branches had been trimmed off straight and smooth like a wall. Then the tops had been trained to meet overhead, and the foliage had been trimmed square and flat on the upper side, and in an arch on the under side. So dense was the growth of the leaves and branches that the whole alley was closely and completely enclosed, so that it would not have been possible to look out of it at all, had it not been that a row of square openings like windows had been made on the side towards the lake. Any one could look out and view the scenery through these openings as he walked along.

Voltaire used to compose his works in this alley, it was said. He would walk up and down, and dictate as he walked to his amanuensis, who sat near at hand with pen and ink to write down the philosopher's words.

After this the domestic conducted the party through a wood, and showed them a tree which Voltaire had planted. It was now a tree of great size, and apparently far advanced in age.

Rollo took very little interest in this tree, and even his father and mother did not appear to pay much attention to it. It seemed, however, that other visitors had not felt the same indifference to it, for those who had come to see it had picked off and cut off so many pieces of bark to carry away as relics that the tree, on one side had become entirely excoriated, and there was danger that in the end the poor sufferer from these depredations would be killed. In order to protect it, therefore, from any further injury, the proprietor had surrounded it with a little circular paling, so that now nobody could come near enough to touch the tree.

Rollo was glad when the visit to this place was ended; so he ran on before his father and mother in going out, and was on his seat by the side of the postilion long before they came to the carriage.

Ferney, though so near to Geneva, is within the confines of France, and the carriage passed the line between the two countries in going home. There was a little custom house and two or three armed policemen at the frontier; but the party of travellers were not molested, and so in due time they arrived safely home.

Chapter VII.

The Junction of the Arve

One evening, when Rollo was walking with his father and mother on one of the bridges which led over the river, they stopped at a place where two boys were fishing, and looked down over the railing into the water. The water was quite deep, but they could see the stones on the bottom of it almost as distinctly as if they had been looking only through the air.

"How very clear the water is!" said Mrs. Holiday; "and what a beautiful tinge it has! What is the reason of it?"

"I don't know what the reason is of the blue tinge," said Mr. Holiday; "but the cause of its being so clear is, that it flows out of this great lake, where it has been lying so long that it has had time to settle perfectly.

"There is a great difference in the streams of Switzerland," continued Mr. Holiday. "Some are exceedingly clear, and some are exceedingly turbid. There are two ways by which the turbid waters become purified. One is, by being filtered through the sands under ground; and the other is, by 'settling', as we call it, in the lakes. The water of the fountain that we saw on our way to Ferney was beautifully clear, and it was made so by filtration in the sand, in coming down through the heart of the mountain. This water, on the other hand, is made clear by its impurities subsiding in the lake."

"And it comes in muddy at the other end," said Rollo.

"Not muddy, exactly," rejoined Mr. Holiday, "but very turbid. The turbidness of it is not mud precisely. It comes from the grinding up of rocks by the slow march of the glaciers over and among them. Thus all the streams that come from glaciers are very turbid; and so long as the waters flow on in an uninterrupted stream they continue turbid; but when they form a lake, the particles of stone subside, and the water comes out at the lower end of the lake perfectly clear."

"And then continues clear till it gets to the ocean, I suppose," said Mrs. Holiday.

"Yes," replied Mr. Holiday, "unless some other turbid stream, which has no lake to settle itself in, falls into it and pollutes it again.

"That is the case with this river. It is very clear and beautiful here, where it comes out of the lake, but the Arve comes in a mile or two below Geneva, and brings an immense volume of turbid water. This makes the whole river turbid again after the waters of the two rivers have flowed long enough together to get well mixed, and then it continues turbid all the way to the sea. There is no other lake to settle it.

"I am told," said Mr. Holiday, "that the coming in of the turbid torrent of the Arve into the clear blue waters of the Rhone is a very pretty spectacle, and I should like very much to see it; but it is rather too far to go."

"O, no, father," said Rollo; "let us go."

"How far is it?" asked Mrs. Holiday.

"About a mile, I should think, by the map," said Mr. Holiday; "but there seems to be no carriage road to the place. If there had been a carriage road I should have taken you there; for I should like very well to have you see the place."

"But, father, we can walk there very easily," said Rollo. "There is a nice path along the bank of the river. I saw it the other day, when I was down below the bridge."

"Well," said Mrs. Holiday, "I should like to go very much, if we could go in the morning or in the evening, when it is cool. Is the walk shady, Rollo?"

"Yes, mother, it is shady in the morning. There is a high hedge all along on one side of the path, and that keeps the sun off in the morning. In the evening the sun comes round to the other side."

"Then we will go in the morning," said Mrs. Holiday. "Let us get up early to-morrow morning, and go before breakfast."

Mrs. Holiday was really desirous of seeing this famous junction of the Rhone and the Arve; but her chief interest in making the excursion arose from her sympathy with Rollo, and from observing how much he wished to go. It is always so with a mother. When her children are kind and attentive to her, and obedient to her wishes, she always desires most strongly to do what will most gratify them.

The plan was arranged according to Mrs. Holiday's proposal, and the next morning the party set out at half past six o'clock. Rollo led the way.

"What I should like best," said Rollo, turning round so as to face his father and mother, and walking backward, "would be to take a boat, and shoot down the river under these bridges."

"Ah," said his father, "that would not do. The current is too swift. At any rate, if you were to go down you would never get the boat back again. The water runs like a mill race.

"Indeed, it is a mill race," continued Mr. Holiday. "Don't you see the mill wheels projecting into the stream, here and there? They are carried by the natural force of the current."

After passing by the buildings of the town, Rollo led the way over a narrow wooden bridge, which passed across the old moat of the town. The remains of a monstrous bastion were to be seen beyond it.

"This is a part of the old fortifications," said Rollo. "They are cutting them all to pieces now with roads and bridges leading in and out the town."

After going beyond these embankments, Rollo led the way to a path which lay along the river side. Very soon the path began to be a very pleasant one indeed. Mrs. Holiday was delighted with it. It was close to the margin of the water, and only a very few inches above the level of it. The current was very swift, and the water was so blue, and clear, and beautiful, that it was a continual pleasure to look down into it, and to watch the little waves and ripples that curled, and twirled, and dashed against the shore.

There was a row of willows between the paths and the water, or rather in the margin of the water, for the path was so near to the stream that there was scarcely room for the willows on the land. On the other side of the path there was a close hedge, which formed the boundary of a region of fields, meadows, and gardens. Here and there were gates leading through this hedge; and the party, as they walked along, could look through the openings and see the peasant girls coming out to their work from the houses. The whole region, though it was highly cultivated and extremely beautiful, was very flat and level, and was only raised two or three feet above the level of the water.

From each gateway or other opening through the hedge there were paths leading off through the fields and gardens to the houses; and there were steps at the gates leading down to the pathway that lay along the margin of the stream. The people of the houses were accustomed, it seemed, to come down there to get water.

Thus the party walked along, with the rapid current of the river close to their feet on one side, and the high green hedge shutting them in on the other, while the tops of the willow trees spreading over their heads completed the coolness and shadiness of the pathway. Rollo led the way, and his father and mother followed, one by one, for the path was not wide enough for two to walk together.

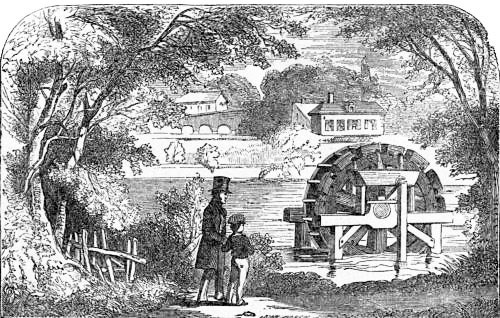

THE WATER WHEEL.

Presently they came to a place where a large water wheel of a very curious construction was seen revolving quite near the shore. They stopped to look at it. They liked to see it revolving; and then besides they wished to examine the construction of it. It was mounted on a frame of timbers that had been set up for it in the water, at a little distance from the shore. The wheel itself was much like the wheel of a steamboat; only, in addition to the ordinary float boards, it had a series of buckets on the edge of it, which took up the water from the stream, as the wheel revolved, and emptied it into a trough above, as they went over. From this trough there was a circular pipe, made very strong, which conveyed the water by a subterranean aqueduct into the field opposite, where it rose into a reservoir by the pressure of the column in the pipe, and was used to irrigate the ground.

Across the river at this place was a beautiful view of fields, vineyards, terraces, and gardens; for on that side the bank was high, and as the sun shone directly upon it, the whole scene presented to view was extremely bright and beautiful.

At one of the gates which opened through the hedge, Rollo stopped to look in. He saw gardens laid out in squares, with corn, and beans, and various garden vegetables growing luxuriantly in them. There were rows of fruit trees, too, bordering the paths, and at a distance were to be seen houses scattered here and there over the plain, the dwellings of the owners of the land. Each house had its little barns and granaries connected with it, the whole group being half concealed by the foliage of the trees and shrubs that had been planted around it.

![Rollo's Philosophy. [Air]](/covers_200/36364270.jpg)