полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 57, No. 356, June, 1845

1

His fondness for books was absolutely insatiable; he was supplied with all the new publications as fast as they appeared; and he would devote the last money in his purse to this purpose. His extravagance in this article of expense he excused by comparing himself to the glazier, whose trade renders it necessary for him to purchase a diamond, an article which a rich man will frequently abstain from buying.

2

The last hours of Púshkin have been minutely and eloquently described by the most distinguished of his friends and brother poets, Jukóvskii, in a letter addressed to Púshkin's father. As this letter contains one of the most touching and beautiful pictures of a great man's death-bed, and as it does equal honour to the author and its subject, we append a translation of it. It is undoubtedly one of the most singular documents in the whole range of literature.—T. B. S.

3

In case we should have done injustice to the poetical inspiration of the Dame Lebrun, we give the originals—

"Tu captives tous les suffrages,Tes talens sont chéris des dieux;Puisse ton nom, dans tous les ages,S'immortaliser avec eux!D'Apollon reçois cette lyre,Pour chanter au sacré vallon;Dans tes mains même on pourra dire,C'est toujours cette d'Apollon!"4

"Que les dieux te courronnent;Moi, je n'ai qu'un verger;Mais le cœur assaisonneLes presens des bergers.Si des fruits de PomoneTu devenais friand,Je te promets, à chaque automne,De t'en offrir autant."5

See Tingry's Painter's and Varnisher's Guide. 1803.

6

Take two pounds two ounces and a half of borax, and one pound of acetate of lead, dissolve each in at least a pint of hot water, mix together the two solutions, and allow the precipitate to subside. Pour off the supernatant liquor as soon as it is clear, add some fresh water (rain water is preferable) to the precipitate, and agitate. Then pour the precipitate, whilst it is distributed throughout this last addition of water, upon a filter of white blotting paper, and when the water has passed through the filter, add more water. These fresh additions of water must be repeated three or four times, merely for the purpose of washing away all traces of the liquor which was retained by the first precipitate, and which was formed by the first admixture of the two solutions. The precipitate, when well washed, is to be placed in a Hessian crucible, and exposed to a red heat for half an hour. A clear glass will be formed; which must be reduced to a very fine powder.

7

"As the very peculiar property which a saturated solution of borax possesses, of uniting so readily with oil in any proportions, has never yet been noticed by chemical writers, I experimented with its constituents, boracic acid and soda, separately, with a view to determine whether the results were to be attributed to the acid, to the alkaline base, or to the particular salt formed by their union.

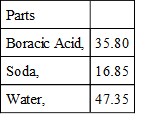

"One hundred parts of borax may be said to consist of:—

Consequently, 24 fluid ounces of water, holding in solution 1 ounce (avoirdupois) of borax, will contain about 4.16 per cent of borax, or 0.702 per cent of soda only.

"I first tried the effect of a saturated aqueous solution of boracic acid with linseed oil. They would not unite. I then prepared some caustic soda by boiling a solution of carbonate of soda with quicklime, decanting the clear caustic liquor, evaporating in a silver crucible, re-dissolving in alcohol, and then distilling the spirit, and heating the residual pure soda to redness. Even in this state, soda contains 23 per cent of water, and only 77 per cent of pure anhydrous soda.

"Ten grains of this soda were dissolved in 1000 grains of distilled water. But as 10 grains of this soda contained only 7.7 grains of anhydrous soda, the 1000 grains of water would contain just 0.770 per cent of soda—a quantity that differs very little from that contained in the saturated aqueous solution of borax.

"Seven measures of the soda solution were added to four measures of linseed oil. This mixture differed so little in appearance, that it might have been mistaken by any casual observer as identical with that produced by a similar proportion of the solution of borax. It had, however, a more soapy odour; and a considerable separation of its constituent parts occurred almost immediately after agitation. This separation increased for many days. The lower liquid was of a foxy brown colour, and, after a week's repose, it amounted to 38 parts out of 59. The upper 21 parts were white and saponaceous. I tried other proportions of soda solutions with oil, but none resembled the results obtained from solutions of borax with oil.

"Fancying that solutions of the bi-carbonate of soda might be more analogous to those of the bi-borate of soda in their effects upon oil, than solutions of caustic soda, I tried many mixtures of solutions of the bi-carbonate with oil; but they were all dissimilar, in appearance, odour, and properties, from like mixtures prepared with the bi-borate of soda."—Letter from C. Thornton Coathupe, Esq., on Vehicles for Pigments. Published in the Art Union of February 1832.

8

We are greatly multiplying artists, by "the promise to the ear," and by our Art-Unions; whether we are like to have such returns to the Commissioners of the Income-tax as those we have quoted, as a consequence of our forced and hot-bed encouragement, remains to be seen. Lord Brougham objects to the railroad mania, on account of the beggary to be induced when the employment they give rise to is over. When the ferment of patronage shall again have settled down to a selection of a few favourites, may we not entertain somewhat similar fears?

9

Some readers may be apt to suppose, from all English experience, that the word exorcise means properly banishment to the shades. Not so. Citation from the shades, or sometimes the torturing coercion of mystic adjurations, is more truly the primary sense.

10

"Laughter from the fields of ocean."—Many readers will recall, though at the moment of writing my own thoughts did not recall, the well-known passage in the Prometheus—

——ωονλιων τε κυματωνΑνηζιθμον Ϛελασμα"Oh multitudinous laughter of the ocean billows!" It is not clear whether Æschylus contemplated the laughter as addressing the ear or the eye.

11

This, it may be said, requires a corresponding duration of experience; but, as an argument for this mysterious power lurking in our nature, I may remind the reader of one phenomenon open to the notice of every body, viz. the tendency of very aged persons to throw back and concentrate the light of their memory upon scenes of early childhood, as to which they recall many traces that had faded even to themselves in middle life, whilst they often forget altogether the whole intermediate stages of their experience. This shows that naturally, and without violent agencies, the human brain is by tendency a palimpsest.

12

"Glimmering."—As I have never allowed myself to covet any man's ox nor his ass, nor any thing that is his, still less would it become a philosopher to covet other people's images, or metaphors. Here, therefore, I restore to Mr Wordsworth this fine image of the revolving wheel, and the glimmering spokes, as applied by him to the flying successions of day and night. I borrowed it for one moment in order to point my own sentence; which being done, the reader is witness that I now pay it back instantly by a note made for that sole purpose. On the same principle I often borrow their seals from young ladies—when closing my letters. Because there is sure to be some tender sentiment upon them about "memory," or "hope," or "roses," or "reunion:" and my correspondent must be a sad brute who is not touched by the eloquence of the seal, even if his taste is so bad that he remains deaf to mine.

13

This, the reader will be aware, applies chiefly to the cotton and tobacco States of North America; but not to them only: on which account I have not scrupled to figure the sun, which looks down upon slavery, as tropical—no matter if strictly within the tropics, or simply so near to them as to produce a similar climate.

14

"Sublime Goddesses."—The word σεμνος is usually rendered venerable in dictionaries; not a very flattering epithet for females. But by weighing a number of passages in which the word is used pointedly, I am disposed to think that it comes nearest to our idea of the sublime; as near as a Greek word could come.

15

The reader, who wishes at all to understand the course of these Confessions, ought not to pass over this dream-legend. There is no great wonder that a vision, which occupied my waking thoughts in those years, should re-appear in my dreams. It was in fact a legend recurring in sleep, most of which I had myself silently written or sculptured in my daylight reveries. But its importance to the present Confessions is this—that it rehearses or prefigures their course. This first part belongs to Madonna. The third belongs to the "Mater Suspiriorum," and will be entitled The Pariah Worlds. The fourth, which terminates the work, belongs to the "Mater Tenebrarum," and will be entitled The Kingdom of Darkness. As to the second, it is an interpolation requisite to the effect of the others; and will be explained in its proper place.

16

"Spectre of the Brocken."—This very striking phenomenon has been continually described by writers, both German and English, for the last fifty years. Many readers, however, will not have met with these descriptions: and on their account I add a few words in explanation; referring them for the best scientific comment on the case to Sir David Brewster's "Natural Magic." The spectre takes the shape of a human figure, or, if the visitors are more than one, then the spectres multiply; they arrange themselves on the blue ground of the sky, or the dark ground of any clouds that may be in the right quarter, or perhaps they are strongly relieved against a curtain of rock, at a distance of some miles, and always exhibiting gigantic proportions. At first, from the distance and the colossal size, every spectator supposes the appearance to be quite independent of himself. But very soon he is surprised to observe his own motions and gestures mimicked; and wakens to the conviction that the phantom is but a dilated reflection of himself. This Titan amongst the apparitions of earth is exceedingly capricious, vanishing abruptly for reasons best known to himself, and more coy in coming forward than the Lady Echo of Ovid. One reason why he is seen so seldom must be ascribed to the concurrence of conditions under which only the phenomenon can be manifested: the sun must be near to the horizon, (which of itself implies a time of day inconvenient to a person starting from a station as distant as Elbingerode;) the spectator must have his back to the sun; and the air must contain some vapour—but partially distributed. Coleridge ascended the Brocken on the Whitsunday of 1799, with a party of English students from Goettingen, but failed to see the phantom; afterwards in England (and under the same three conditions) he saw a much rarer phenomenon, which he described in the following eight lines. I give them from a corrected copy: (the apostrophe in the beginning must be understood as addressed to an ideal conception):—

"And art thou nothing? Such thou art as whenThe woodman winding westward up the glenAt wintry dawn, when o'er the sheep-track's mazeThe viewless snow-mist weaves a glist'ning haze,Sees full before him, gliding without tread,An image with a glory round its head:This shade he worships for its golden hues,And makes (not knowing) that which he pursues."17

"On Whitsunday."—It is singular, and perhaps owing to the temperature and weather likely to prevail in that early part of summer, that more appearances of the spectre have been witnessed on Whitsunday than on any other day.

18

"The sorcerer's flower," and "the sorcerer's altar."—These are names still clinging to the anemone of the Brocken, and to an altar-shaped fragment of granite near one of the summits; and it is not doubted that they both connect themselves through links of ancient tradition with the gloomy realities of Paganism, when the whole Hartz and the Brocken formed for a very long time the last asylum to a ferocious but perishing idolatry.

19

"The sorcerer's flower," and "the sorcerer's altar."—These are names still clinging to the anemone of the Brocken, and to an altar-shaped fragment of granite near one of the summits; and it is not doubted that they both connect themselves through links of ancient tradition with the gloomy realities of Paganism, when the whole Hartz and the Brocken formed for a very long time the last asylum to a ferocious but perishing idolatry.

20

"Hailstone choruses."—I need not tell any lover of Handel that his oratorio of "Israel in Egypt" contains a chorus familiarly known by this name. The words are—"And he gave them hailstones for rain; fire, mingled with the hail, ran along upon the ground."

21

History of Rome. By Thomas Arnold, D.D. London: 1843. Vol. 3.

22

Hannibal was born in the year 247 before Christ, or 2092 before this time.

23

Virtus from vir—exercitus from exerceo.

24

Arnold, iii. 89.

25

Ibid. iii. 486, note.

26

Livy, xxi. 33.

27

Polybius, iii. 52.

28

Ibid. iii. 54.

29

"The way on every side was utterly impassable, through an accident of a peculiar kind, which is peculiar to the Alps. The snows of the former years having remained unmelted upon the mountains, were now covered over by that which had fallen in the present autumn, and when the soldiers feet went through the latter they fell, and slid down with great violence."—Polybius, iii. 54. This shows the place was within the circle of perpetual snow; whereas that on the Little St Bernard is much below it, and far beneath any avalanches.

30

Polybius, iii. 54.

31

Arnold, iii. 64, 65

32

See Arnold's Rome, Blackwood's Magazine, July 1837.

33

In his beautiful Ode to Melancholy; originally published in Blackwood's Magazine.

34

See his Plea of the Midsummer Fairies, a poem perfectly unrivalled for the intimate sense of nature, tender fancy, and pathetic playfulness displayed in it.

35

"Pity it was to hear the Elfins' wailRise up in concert from their mingled dread,Pity it was to see them all so paleGaze on the grass as for a dying bed.But Puck was seated on a spider's threadThat hung between two branches of a brier,And 'gan to swing and gambol, heels o'er head,Like any Southwark tumbler on a wire,For him no present grief could long inspire."Plea of the Midsummer Fairies.36

Witness the terror of Aram after his victim lies dead before him—(we quote from memory.)

"Nothing but lifeless flesh and boneThat could not do me ill!And yet I fear'd him all the moreFor lying there so still;There was a manhood in his lookThat murder could not kill."Dream of Eugene Aram.37

"For Guilt was my grim chamberlainWho lighted me to bed,And drew my midnight curtains roundWith fingers bloody red."Dream of Eugene Aram.38

See his impressive poem on The Elm-Tree. It appeared, a couple of years back, in The New Monthly Magazine.

39

"Before I lived to sigh,Thou wert in Avon, and a thousand rills,Beautiful Orb! and so, whene'er I lieTrodden, thou wilt be gazing from thy hills.Blest be thy loving light, where'er it spills,And blessed be thy face, O Mother Mild!" Ode to the Moon, published likewise in Blackwood, 1829.