полная версия

полная версияHarper's New Monthly Magazine, Vol. 3, July, 1851

"For cutting off our trade with all parts of the world;

"For imposing taxes on us without our consent;

"For depriving us, in many cases, of the benefits of trial by jury;

"For transporting us beyond seas to be tried for pretended offenses:

"For abolishing the free system of English laws in a neighboring province, establishing therein an arbitrary government, and enlarging its boundaries, so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these colonies;

"For taking away our charters, abolishing our most valuable laws, and altering, fundamentally, the forms of our governments;

"For suspending our own legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

"He has abdicated government here by declaring us out of his protection and waging war against us.

"He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

"He is at this time transporting large armies of foreign mercenaries to complete the works of death, desolation, and tyranny, already begun, with circumstances of cruelty and perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the head of a civilized nation.

"He has constrained our fellow-citizens, taken captive on the high seas, to bear arms against their country, to become the executioners of their friends and brethren, or to fall themselves by their hands.

"He has excited domestic insurrections among us, and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers the merciless Indian savages, whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions.

"In every stage of these oppressions, we have petitioned for redress in the most humble terms. Our repeated petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

"Nor have we been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them, from time to time, of attempts, by their legislature, to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them, by the ties of our common kindred, to disavow these usurpations, which would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They, too, have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity which denounces our separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, enemies in war, in peace friends.

"We, therefore, the representatives of the United States of America, in general Congress assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the World for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the name, and by the authority of the good people of these colonies, solemnly publish and declare that these united colonies are, and of right ought to be free and independent states; that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British crown, and that all political connection between them and the state of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved; and that, as free and independent states, they have full power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce, and to do all other acts and things which independent states may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor."

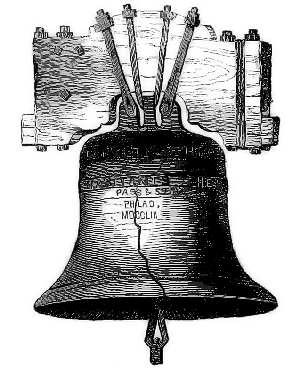

LIBERTY BELL.

It was almost two o'clock in the afternoon when the final decision was announced by Secretary Thomson, to the assembled Congress in Independence Hall. It was a moment of solemn interest; and when the secretary sat down, a deep silence pervaded that august assembly. Tradition says that it was first broken by Dr. Franklin, who remarked, "Gentlemen, we must now all hang together, or we shall surely hang separately." Thousands of anxious citizens had gathered in the streets of Philadelphia, for it was known that the final vote would be taken on that day. From the hour when Congress convened in the morning, the old bell-man had been in the steeple. He had placed a boy at the door below, to give him notice when the announcement should be made. As hour succeeded hour, the graybeard shook his head, and said, "They will never do it! they will never do it!" Suddenly a loud shout came up from below, and there stood the little blue-eyed boy clapping his hands, and shouting, "Ring! Ring!" Grasping the iron tongue of the old bell, backward and forward he hurled it a hundred times, its loud voice proclaiming "Liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof."2 The excited multitude in the streets responded with loud acclamations, and with cannon peals, bonfires, and illuminations, the patriots held a glorious carnival that night in the quiet city of Penn.

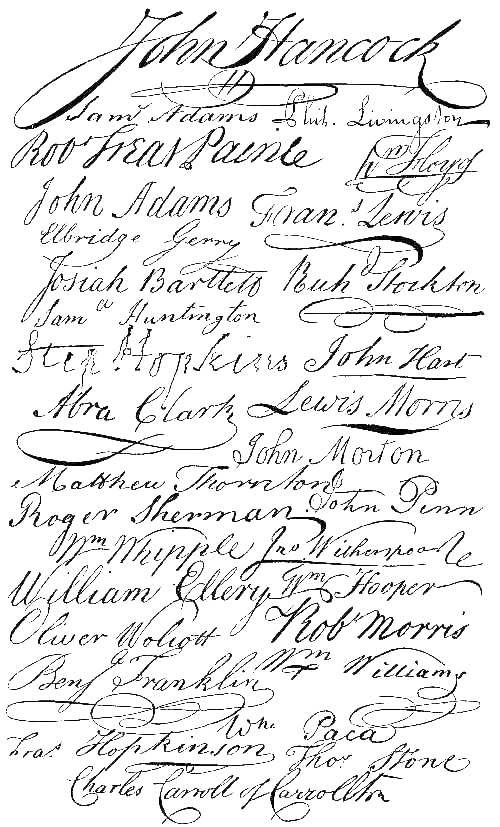

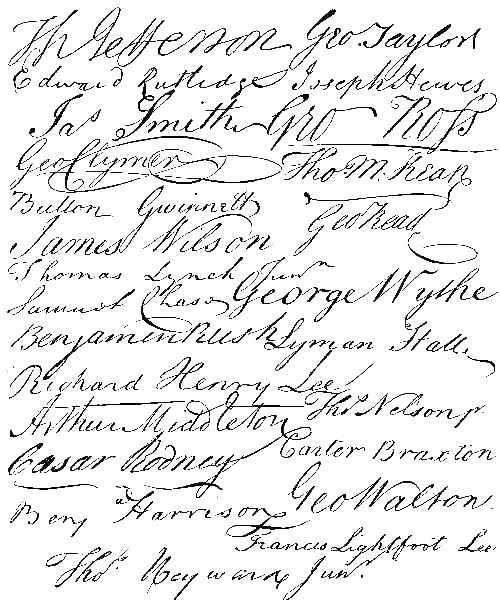

The Declaration of Independence was signed by John Hancock, the President of Congress, only, on the day of its adoption, and thus it went forth to the world. Congress ordered it to be entered at length upon the journals; it was also ordered to be engrossed upon parchment for the delegates to sign it. This last act was performed on the second day of August ensuing, by the fifty-four delegates then present. Thomas M'Kean, of Delaware, and Dr. Thornton, of New Hampshire, subsequently signed it, making the whole number fifty-six. Upon the next two pages are their names, copied from the original parchment, which is carefully preserved in a glass case, in the rooms of the National Institute, Washington City. It is our pride and righteous boast, and it should be the pride and boast of mankind, that not one of those patriots who signed that manifesto ever fell from the high moral elevation which he then held: of all that band, not one, by word or act, tarnished his fair fame.

The great Declaration was every where applauded; and, in the camp, in cities, villages, churches, and popular assemblies, it was greeted with every demonstration of joy. Washington received it at head-quarters, in New York, on the ninth of July, and caused it to be read aloud at six o'clock that evening at the head of each brigade. It was heard with attention, and welcomed with loud huzzas by the troops. The people echoed the acclaim, and on the same evening they pulled down the leaden statue of the king, which was erected in the Bowling-Green, at the foot of Broadway, in 1770, broke it in pieces, and consigned the materials to the bullet-moulds.

SIGNATURES ON THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE.

At noon, on the seventeenth of July, Colonel Crafts read the Declaration to a vast assemblage gathered in and around Faneuil Hall, in Boston, and when the last paragraph fell from his lips, a loud huzza shook the old "Cradle of Liberty." It was echoed by the crowd without, and soon the batteries on Fort Hill, Dorchester, Nantasket, Long Island, the Castle, and the neighboring heights of Charlestown, Cambridge, and Roxbury boomed forth their cannon acclamations in thirteen rounds. A banquet followed, and bonfires and illuminations made glad the city of the Puritans.

SIGNATURES ON THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE.

On the eighth, John Nixon read it from the Walnut-street front of the State House, in Philadelphia, to a great concourse of people gathered from the city and the surrounding country. When the reading was finished, the king's arms over the seat of Justice in the courtroom, was torn down and burnt in the street; and at evening bonfires were lighted, the city was illuminated, and it was not until a thunder-storm at midnight compelled the people to retire, that the sounds of gladness were hushed. Newport, Providence, Hartford, Baltimore, Annapolis, Williamsburg, Charleston, Savannah, and other towns near the seaboard, made similar demonstrations, and loyalty to the king, hitherto open-mouthed, was silent and abashed.

From every inhabited hill and valley, town and hamlet of the old thirteen States, arose the melodies of Freedom, awakened by this great act of the people's proxies; and thousands of hearts in Europe, beating strongly with hopes for the future, were deeply impressed and comforted. Bold men caught the symphony, and prolonged its glad harmony, even beyond the Alps and the Apennines, until it wooed sleeping slaves from their slumbers in the shadows of despotism forth into the clear light, panoplied in the armor of absolute right and justice. France was aroused, and turning in its bed of submission like the giant beneath old Ætna, to look for light and liberty, an earthquake shock ensued which shook thrones, crumbled feudal altars whereon equality was daily sacrificed, and so rent the vail of the temple of despotism, that the people saw plainly the fetters and instruments of unholy rule, huge and terrible, within the inner court. They pulled down royalty, overturned distinctions, and gave the first impulse to the civil and social revolutions which have since spread from that focus, to purify the political atmosphere of Europe. Back to our glorious manifesto the struggling nations look; and when they wish to arraign their tyrants, that indictment is their text and guide. Its specific charges against the ruler of Great Britain, of course have no relevancy in other cases, but the great truths set forth in the Declaration are immutable. Always appropriate as a basis of governmental theory and practice, at all times and in all places, they can not fail to receive the hearty concurrence of the wise and good in all lands, and under all circumstances. They were early appreciated by the philosophers and statesmen of Europe, and that appreciation augments with the flight of years.

"With what grandeur, with what enthusiasm, should I not speak of those generous men who erected this grand edifice by their patience, their wisdom, and their courage!" wrote the Abbé Raynal, in 1781, when descanting upon our Declaration. "Hancock, Franklin, and the two Adamses, were the greatest actors in this affecting scene: but they were not the only ones. Posterity shall know them all. Their honored names shall be transmitted to it by a happier pen than mine. Brass and marble shall show them to remotest ages. In beholding them shall the friend of freedom feel his heart palpitate with joy; feel his eyes float in delicious tears. Under the bust of one of them has been written: he wrested thunder from heaven, and the sceptre from tyrants.3 Of the last words of this eulogy shall all of them partake. Heroic country, my advanced age permits me not to visit thee. Never shall I see myself among the respectable personages of thy Areopagus; never shall I be present at the deliberations of thy Congress. I shall die without seeing the retreat of toleration, of manners, of laws, of virtue, and of freedom. My ashes shall not be covered by a free and holy earth: but I shall have desired it; and my last breath shall bear to heaven an ejaculation for thy prosperity."

"I ask," exclaimed Mirabeau, in the tribune of the National Assembly of France, "if the powers who have formed alliances with the States have dared to read that manifesto, or to interrogate their consciences after the perusal? I ask whether there be at this day one government in Europe—the Helvetic and Batavian confederations, and the British isles excepted, which, judged after the principles of the Declaration of Congress on the fourth of July 1776, is not divested of its rights?" And Napoleon, afterward alluding to the same scene, said, "The finger of God was there!"

The fourth of July, marked by an event so momentous, is properly our great National Anniversary. For three-quarters of a century it has been commemorated by orations, firing of cannon, ringing of bells, military parades, fireworks, squibs, and bonfires; and, alas! too often the day has been desecrated by bacchanalian revels. The deep feelings which stirred the spirits of those who participated in the scenes of the Revolution, on the recurrence of the anniversary, warm not the hearts of their children. With them the Declaration of Independence was a great, and ever-present reality; with us it is only a glorious abstract idea. We are in the midst of the fruition of their faith and earnest aspirations; and, surrounded by the noon-tide radiance of the blessings which have resulted from that act, we can not appreciate the glory of the morning star of our destiny as a nation. Let us henceforth aim to be less superficial in our views of the National Anniversary. Let orators cease grandiloquent displays of bombastic rhetoric, "full of sound and fury, signifying nothing," and discourse with the sober earnestness of true philosophy upon the antecedents—the remote springs—of that event, every where visible in the history of the world; and by expatiating upon the principles set forth in our manifesto, and their salutary effect upon the well-being of mankind, give practical force to their vitality. Huzzas are not arguments for thinking men; and now, when thought is every where busy in the formation of omnipotent opinion, the American should cast off the garb of national pride, and with the cosmopolitan spirit of a true missionary of Freedom, point to the eternal bond of Union which binds our sovereign States together, and explain the character of its strength and vigor. Placed by the side of the principles involved in our struggle for Independence, the men and their councils, battles, sieges, and victories, wane into comparative insignificance. They are but the nerves and muscles, the sinews and the blood of the being we apotheosize—the mere aids of the mighty brain, the seat of the controlling spirit of the whole. Let us always revere those essential aids, and cherish them in our heart of hearts, but worship only the puissant Spirit on our National Anniversary.

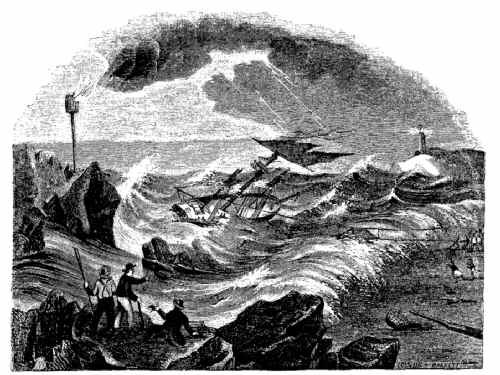

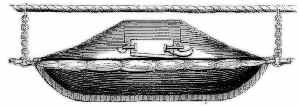

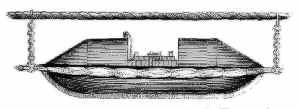

THE LIFE-CAR.

SOME ACCOUNT OF FRANCIS'S LIFE-BOATS AND LIFE-CARS

BY JACOB ABBOTTTHE engraving at the head of this article represents the operation of transporting the officers and crew of a wrecked vessel to the shore, by means of one of the Life-Cars invented by Mr. Joseph Francis for this purpose. A considerable appropriation was made recently by Congress, to establish stations along the coast of New Jersey and Long Island—as well as on other parts of the Atlantic seaboard—at which all the apparatus necessary for the service of these cars, and of boats, in cases where boats can be used, may be kept. These stations are maintained by the government, with the aid and co-operation of the Humane Society—a benevolent association the object of which is to provide means for rescuing and saving persons in danger of drowning—and also of the New York Board of Underwriters, a body, which, as its name imports, represents the principal Marine Insurance Companies—associations having a strong pecuniary interest in the saving of cargoes of merchandize, and other property, endangered in a shipwreck. These three parties, the Government, the Humane Society, and the Board of Underwriters, combine their efforts to establish and sustain these stations; though we can not here stop to explain the details of the arrangement by which this co-operation is effected, as we must proceed to consider the more immediate subject of this article, which is the apparatus and the machinery itself, by which the lives and property are saved. In respect to the stations, however, we will say that it awakens very strong and very peculiar emotions in the mind, to visit one of them on some lonely and desolate coast, remote from human dwellings, and to observe the arrangements and preparations that have been made in them, all quietly awaiting the dreadful emergency which is to call them into action. The traveler stands for example on the southern shore of the island of Nantucket, and after looking off over the boundless ocean which stretches in that direction without limit or shore for thousands of miles, and upon the surf rolling in incessantly on the beach, whose smooth expanse is dotted here and there with the skeleton remains of ships that were lost in former storms, and are now half buried in the sand, he sees, at length, a hut, standing upon the shore just above the reach of the water—the only human structure to be seen. He enters the hut. The surf boat is there, resting upon its rollers, all ready to be launched, and with its oars and all its furniture and appliances complete, and ready for the sea. The fireplace is there, with the wood laid, and matches ready for the kindling. Supplies of food and clothing are also at hand—and a compass: and on a placard, conspicuously posted, are the words,

Shipwrecked mariners reaching this hut, in fog or snow, will find the town of Nantucket two miles distant, due west.

It is impossible to contemplate such a spectacle as this, without a feeling of strong emotion—and a new and deeper interest in the superior excellency and nobleness of efforts made by man for saving life, and diminishing suffering, in comparison with the deeds of havoc and destruction which have been so much gloried in, in ages that are past. The Life-Boat rests in its retreat, not like a ferocious beast of prey, crouching in its covert to seize and destroy its hapless victims, but like an angel of mercy, reposing upon her wings, and watching for danger, that she may spring forth, on the first warning, to rescue and save.

The Life-Car is a sort of boat, formed of copper or iron, and closed over, above, by a convex deck with a sort of door or hatchway through it, by which the passengers to be conveyed in it to the shore, are admitted. The car will hold from four to five persons. When these passengers are put in, the door, or rather cover, is shut down and bolted to its place; and the car is then drawn to the land, suspended by rings from a hawser which has previously been stretched from the ship to the shore.

To be shut up in this manner in so dark and gloomy a receptacle, for the purpose of being drawn, perhaps at midnight, through a surf of such terrific violence that no boat can live in it, can not be a very agreeable alternative; but the emergencies in which the use of the life-car is called for, are such as do not admit of hesitation or delay. There is no light within the car, and there are no openings for the admission of air.4 It is subject, too, in its passage to the shore, to the most frightful shocks and concussions from the force of the breakers. The car, as first made, too, was of such a form as required the passengers within it to lie at length, in a recumbent position, which rendered them almost utterly helpless. The form is, however, now changed—the parts toward the ends, where the heads of the passengers would come, when placed in a sitting posture within, being made higher than the middle; and the opening or door is placed in the depressed part, in the centre. This arrangement is found to be much better than the former one, as it greatly facilitates the putting in of the passengers, who always require a greater or less degree of aid, and are often entirely insensible and helpless from the effects of fear, or of exposure to cold and hunger. Besides, by this arrangement those who have any strength remaining can take much more convenient and safer positions within the car, in their progress to the shore, than was possible under the old construction.

The car, as will be seen by the foregoing drawings, is suspended from the hawser by means of short chains attached to the ends of it. These chains terminate in rings above, which rings ride upon the hawser, thus allowing the car to traverse to and fro, from the vessel to the shore. The car is drawn along, in making these passages, by means of lines attached to the two ends of it, one of which passes to the ship and the other to the shore. By means of these lines the empty car is first drawn out to the wreck by the passengers and crew, and then, when loaded, it is drawn back to the land by the people assembled there, as represented in the engraving at the head of this article.

Perhaps the most important and difficult part of the operation of saving the passengers and crew in such cases, is the getting the hawser out in the first instance, so as to form a connection between the ship and the land. In fact, whenever a ship is stranded upon a coast, and people are assembled on the beach to assist the sufferers, the first thing to be done, is always to "get a line ashore." On the success of the attempts made to accomplish this, all the hopes of the sufferers depend. Various methods are resorted to, by the people on board the ship, in order to attain this end, where there are no means at hand on the shore, for effecting it. Perhaps the most common mode is to attach a small line to a cask, or to some other light and bulky substance which the surf can easily throw up upon the shore. The cask, or float, whatever it may be, when attached to the line, is thrown into the water, and after being rolled and tossed, hither and thither, by the tumultuous waves, now advancing, now receding, and now sweeping madly around in endless gyrations, it at length reaches a point where some adventurous wrecker on the beach can seize it, and pull it up upon the land. The line is then drawn in, and a hawser being attached to the outer end of it, by the crew of the ship, the end of the hawser itself is then drawn to the shore.

THE CASK.

This method, however, of making a communication with the shore from a distressed vessel, simple and sure as it may seem in description, proves generally extremely difficult and uncertain in actual practice. Sometimes, and that, too, not unfrequently when the billows are rolling in with most terrific violence upon the shore, the sea will carry nothing whatever to the land. The surges seem to pass under, and so to get beyond whatever objects lie floating upon the water, so that when a cask is thrown over to them, they play beneath it, leaving it where it was, or even drive it out to sea by not carrying it as far forward on their advance, as they bring it back by their recession. Even the lifeless body of the exhausted mariner, who when his strength was gone and he could cling no longer to the rigging, fell into the sea, is not drawn to the beach, but after surging to and fro for a short period about the vessel, it slowly disappears from view among the foam and the breakers toward the offing. In such cases it is useless to attempt to get a line on shore from the ship by means of any aid from the sea. The cask intrusted with the commission of bearing it, is beaten back against the vessel, or is drifted uselessly along the shore, rolling in and out upon the surges, but never approaching near enough to the beach to enable even the most daring adventurer to reach it.

In case of these life-cars, therefore, arrangements are made for sending the hawser out from the shore to the ship. The apparatus by which this is accomplished consists, first, of a piece of ordnance called a mortar, made large enough to throw a shot of about six inches in diameter; secondly, the shot itself, which has a small iron staple set in it; thirdly, a long line, one end of which is to be attached to the staple in the shot, when the shot is thrown; and, fourthly, a rack of a peculiar construction to serve as a reel for winding the line upon. This rack consists of a small square frame, having rows of pegs inserted along the ends and sides of it. The line is wound upon these pegs in such a manner, that as the shot is projected through the air, drawing the line with it, the pegs deliver the line as fast as it is required by the progress of the shot, and that with the least possible friction. Thus the advance of the shot is unimpeded. The mortar from which the shot is fired, is aimed in such a manner as to throw the missile over and beyond the ship, and thus when it falls into the water, the line attached to it comes down across the deck of the ship, and is seized by the passengers and crew.