полная версия

полная версияHarper's New Monthly Magazine, Vol. 3, July, 1851

The host saw his triumph. "Now for another dance!" said he, gayly; and he was about to offer his hand to Mrs. M'Catchley, when Sir Compton Delaval, seizing it, and giving it a hearty shake, cried, "You have not yet danced with my eldest daughter; so, if you won't ask her, why, I must offer her to you as your partner. Here—Sarah."

Miss Sarah Delaval, who was five feet eight, and as stately as she was tall, bowed her head graciously; and Mr. Avenel, before he knew where he was, found her leaning on his arm. But as he passed into the next division of the tent, he had to run the gauntlet of all the gentlemen who thronged round to shake hands with him. Their warm English hearts could not be satisfied till they had so repaired the sin of their previous haughtiness and mockery. Richard Avenel might then have safely introduced his sister—gown, kerchief, thick shoes and all—to the crowd; but he had no such thought. He thanked heaven devoutly that she was safely under lock and key.

It was not till the third dance that he could secure Mrs. M'Catchley's hand, and then it was twilight. The carriages were at the door, but no one yet thought of going. People were really enjoying themselves. Mr. Avenel had had time, in the interim, to mature all his plans for completing and consummating that triumph which his tact and pluck had drawn from his momentary disgrace. Excited as he was with wine and suppressed passion, he had yet the sense to feel that, when all the halo that now surrounded him had evaporated, and Mrs. M'Catchley was redelivered up to the Pompleys, whom he felt to be the last persons his interest could desire for her advisers—the thought of his low relations would return with calm reflection. Now was the time. The iron was hot—now was the time to strike it, and forge the enduring chain.

As he led Mrs. M'Catchley after the dance, into the lawn, he therefore said tenderly—

"How shall I thank you for the favor you have done me?"

"Oh!" said Mrs. M'Catchley, warmly, "it was no favor—and I am so glad"—She stopped.

"You're not ashamed of me, then, in spite of what has happened?"

"Ashamed of you! Why, I should be so proud of you, if I were—"

"Finish the sentence, and say—'your wife!'—there it is out. My dear madam, I am rich, as you know; I love you very heartily. With your help, I think I can make a figure in a larger world than this; and that whatever my father, my grandson at least will be—But it is time enough to speak of him. What say you?—you turn away. I'll not tease you—it is not my way. I said before, ay or no; and your kindness so emboldens me that I say it again—ay or no?"

"But you take me so unawares—so—so—Lord, my dear Mr. Avenel; you are so hasty—I—I—." And the widow actually blushed, and was genuinely bashful.

"Those horrid Pompleys!" thought Richard, as he saw the Colonel bustling up with Mrs. M'Catchley's cloak on his arm.

"I press for your answer," continued the suitor, speaking very fast. "I shall leave this place to-morrow, if you will not give it."

"Leave this place—leave me?"

"Then you will be mine?"

"Ah, Mr. Avenel!" said the widow, languidly, leaving her hand in his; "who can resist you?"

Up came Colonel Pompley; Richard took the shawl: "No hurry for that now, Colonel—Mrs. M'Catchley feels already at home here."

Ten minutes afterward Richard Avenel so contrived that it was known by the whole company that their host was accepted by the Honorable Mrs. M'Catchley. And every one said, "He is a very clever man, and a very good fellow," except the Pompleys—and the Pompleys were frantic. Mr. Richard Avenel had forced his way into the aristocracy of the country. The husband of an Honorable—connected with peers!

"He will stand for our city—Vulgarian!" cried the Colonel.

"And his wife will walk out before me," cried the Colonel's lady—"nasty woman!" And she burst into tears.

The guests were gone; and Richard had now leisure to consider what course to pursue with regard to his sister and her son.

His victory over his guests had in much softened his heart toward his relations; but he still felt bitterly aggrieved at Mrs. Fairfield's unseasonable intrusion, and his pride was greatly chafed by the boldness of Leonard. He had no idea of any man whom he had served, or meant to serve, having a will of his own—having a single thought in opposition to his pleasure. He began, too, to feel that words had passed between him and Leonard which could not be well forgotten by either, and would render their close connection less pleasant than heretofore. He, the great Richard Avenel, beg pardon of Mrs. Fairfield, the washerwoman! No; she and Leonard must beg his. "That must be the first step," said Richard Avenel; "and I suppose they have come to their senses." With what expectation, he unlocked the door of his parlor, and found himself in complete solitude. The moon, lately risen, shone full into the room, and lit up every corner. He stared round, bewildered—the birds had flown. "Did they go through the key-hole?" said Mr. Avenel. "Ha! I see—the window is open!" The window reached to the ground. Mr. Avenel, in his excitement, had forgotten that easy mode of egress.

"Well," said he, throwing himself into his easy chair, "I suppose I shall soon hear from them; they'll be wanting my money fast enough, I fancy." His eye caught sight of a letter, unsealed, lying on the table. He opened it, and saw bank-notes to the amount of £50—the widow's forty-five country notes, and a new note, Bank of England, that he had lately given to Leonard. With the money were these lines, written in Leonard's bold, clear writing, though a word or two here and there showed that the hand had trembled—

"I thank you for all you have done to one whom you regarded as the object of charity. My mother and I forgive what has passed. I depart with her. You bade me make my choice, and I have made it. Leonard Fairfield."

The paper dropped from Richard's hand, and he remained mute and remorseful for a moment. He soon felt, however, that he had no help for it but working himself up into a rage. "Of all people in the world," cried Richard, stamping his foot on the floor, "there are none so disagreeable, insolent, and ungrateful as poor relations. I wash my hands of them."

(TO BE CONTINUED.)Monthly Record of Current Events

POLITICAL AND GENERAL NEWS

UNITED STATES

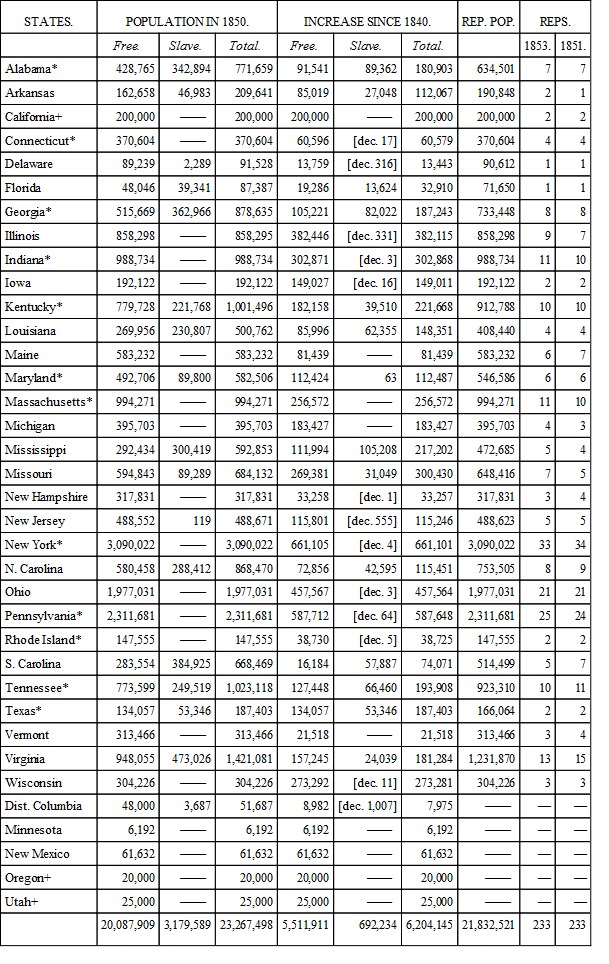

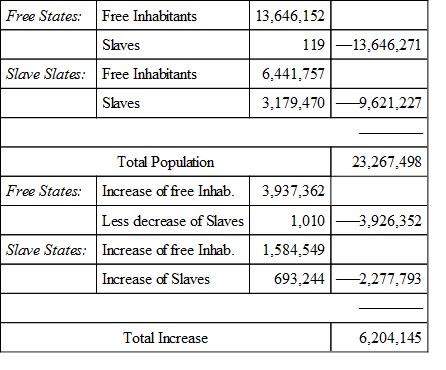

From the abstract of the Seventh Census of the United States, and from the returns of the previous decennial periods, we compile the following table and statements, setting forth the principal features of the increase of the population of the country. The manner of apportioning the Congressional representation was fixed by an Act passed May 23, 1850. From and after March 3, 1853, the House of Representatives, unless otherwise ordained by Congress, is to consist of 233 members. The apportionment is made by adding to the number of free persons three-fifths of the number of slaves: the representative population, thus found, divided by 233, gives the ratio of apportionment: the representative population of each State, divided by this ratio, shows the number of Representatives to which the State is entitled. To the aggregate thus obtained is added a number sufficient to make up the whole number of 233 members; this additional number is apportioned among the States having the largest fractions. It is, however, provided by the Constitution that each State shall be entitled to at least one Representative. The representative population being 21,832,521, the ratio of representation is 93,702. The States which have a Representative for a fraction of the ratio are indicated in the table by a *. Those whose population is estimated are designated by a +.

The Free Colored population, included in the above, numbers 419,173; of whom 184,882 are in the Free States, and 234,291 in the Slave States. Maryland has the highest number, 73,943. They have increased during the last ten years only 32,880, or 7.84 per cent. At the six previous enumerations respectively, there were returned 40,370, 35,946, 27,505, 18,148, 3553, and 1129 slaves from the Free States. The published abstract of the recent census shows only 119, all in New Jersey. The population, and the increase since 1840, are made up of the following elements; the total population of the territories not included in the census of 1840 being considered as increase:

At the last apportionment, the House of Representatives consisted of 223 members, of whom 135 were from the Free States, and 88 from the Slave States; a Free State majority of 47. By the next apportionment there will be 233 members, of whom 144 will be from the Free States, and 89 from the Slave States; a Free State majority of 55: being an increase of 8 above that at the previous apportionment.

The projected invasion of Cuba has entirely miscarried. The bands of adventurers who had been collected at various points have dispersed, none of them having succeeded in getting away from the United States. At Jacksonville, Florida, where some hundreds were at different times congregated, many were indebted to charity for the means of returning to their homes. A number of persons have been arrested on charge of participation in the proposed expedition.

After the celebration of the opening of the New York and Erie Railroad, noticed in our Record of last month, President Fillmore returned to Washington by way of Rochester, Albany, New York, and Philadelphia. He reached the seat of Government on the 24th of May, after an absence of twelve days. Mr. Webster remained behind for a few days, and delivered, at Buffalo, Syracuse, and Albany, a series of elaborate speeches, setting forth his views of the state of public affairs, and explaining and vindicating his course and principles. He expressed his entire and hearty concurrence in all the prominent measures adopted by the Administration. The question, as far as related to the North, was not one of Union or Disunion; but whether the Constitution should be so administered that all the members of the Confederacy could remain within it. He disclaimed, most emphatically all idea of concession; the South should not have a hair's-breadth of concession from him; but he would maintain, to the utmost of his power, and in the face of all danger, the rights, under the Constitution, of the South as well as of the North; "and God forsake me and my children, if I ever be found to falter in one or the other." He gave a sketch of the historical relations of slavery to the Constitution; and insisted that the meaning and intent of the clause providing for the return of fugitives from labor, was so plain and evident, that not an attorney could be found who could raise a doubt about it. It was assumed in many quarters, that if a colored man comes to the North, he comes as a freeman; but, according to the Constitution, if he comes as a fugitive from service or labor, he is not a freeman, and must be delivered up, upon claim of those who are entitled to his services. There was not a man who held office under the General or State Government who was not bound by solemn oath to support and carry out this clause of the Constitution. Mr. W. asserted most emphatically, that he was and ever had been opposed to the admission of new slave territory into the Union, believing that it was beyond the power and against the provisions of the Constitution. He would never consent that there should be one foot of slave-territory beyond what the old Thirteen States had at the time of the formation of the Union. He was not in Congress at the time of the acquisition of Louisiana and Florida. But when the project of the annexation of Texas was about to be brought forward, he had gone out of his way, in a speech at New York, in 1837, to denounce, in advance the annexation of Texas as slave territory to the United States. He then expressed the opinion that the people of the United States would not, and ought not to consent to bring this territory into the Union. But he had proved a false prophet. The State of New York consented to it, and the vote of her Senators decided the question. In Congress, before the final consummation of the deed, he fought against the measure, and he would not now, before the country or the world, consent to be numbered among those who introduced new slave power into the Union. He disliked the Mexican war, and disliked the peace still more, because it brought in new territories. The rush of Northern men to California made it of necessity a Free State. As to New Mexico and Utah, he saw that the existence of slavery there was impossible; and as the South thought that the application of the Wilmot Proviso was irritating and disrespectful, he voted against it; for he was not disposed to give offense without cause. Mr. W. discussed at length the question of the Texas boundary, and proclaimed it as his solemn belief that unless it had been settled by Congress, a civil war would have ensued. The other great question, in 1850, was that of the Fugitive Slave Law. Under the provisions of the Constitution a law for the delivery of fugitives had been passed in 1793, by general consent. It answered its purpose till 1841 or 1842, when the States began to make enactments in opposition to it. Mr. W. was in favor of a proper law; he had, indeed, proposed a different one; he was of the opinion that a trial by jury might be had. But the law of 1850, passed, and he would undertake to say, that it was more favorable to the fugitive than that of 1793; since it placed the matter within the jurisdiction of a higher tribunal. Mr. W. denounced in the severest terms those who counseled resistance to the law; and defended his own course in advocating the Compromise measures. He felt that he had a duty to perform to exert every power to keep the country together, and if the fate of John Rogers had been presented to him, if he had heard the thorns crackling, by the blessing of Almighty God, he would have gone on and discharged the duty which he thought his country called upon him to perform.

No little interest has been awakened by a legal suit brought by the Methodist Episcopal Church South, to recover a portion of the "Book Fund" belonging to the Methodist Episcopal Church before its division. This fund, arising from the sale of books and publications, and devoted to the benefit of traveling, supernumary, superannuated, and worn-out preachers, their wives, widows, and children, amounted, in 1845, when the division in the Church took place, to about $750,000. It was under the charge of the General Conference, with the restriction that they should appropriate it to no other purpose than that above specified, except by a vote of two-thirds, upon the recommendation of three fourths of the members of the Annual Conferences. In 1844, when it seemed apparent that the diversities of opinion in the Church on the subject of slavery, would render a separation advisable, the General Conference recommended to the Annual Conferences to pass resolutions authorizing it to make proper arrangements as to the Fund; and in anticipation of such authorization, appointed a committee to meet one from the South, to make the necessary arrangements for an equitable division. But the separation, thus amicably proposed, did not take place without great exasperation on both sides. In the Annual Conferences the vote authorizing the division was 2135 out of 3205, lacking 269 of the requisite majority of three-fourths. The Northern Commissioners, therefore, decided that they had no authority to act. The separation was formally effected in 1845. In May, 1848, the General Conference, held at Pittsburgh, authorized the Book Agents in New York and Cincinnati, to submit the matter to arbitration, provided that, upon consultation with eminent counsel, they should be satisfied they had the legal power so to do, when clothed with all the authority the General Conference could confer. If the Agents should find that they had no such legal power, they were authorized, in the event of a suit being instituted by the Southern Church, to submit the claims to a legal arbitration, under the authority of a competent court. And in case no suit should be commenced, the General Conference recommended to the Annual Conferences so to suspend the "restrictive clause" as to authorize a voluntary arbitration. Previous to the commencement of this suit, the Bishops had begun to lay the above recommendation before the Annual Conferences. When, however, in June, 1849, a suit was instituted, this proceeding was suspended. The suit came on, upon the 19th of May, in the United States Circuit Court, before Judges Nelson and Betts. It lasted eight days, four of which were occupied with the arguments of counsel—Messrs. Daniel Lord and Reverdy Johnson for the plaintiffs, and Rufus Choate and Geo. Wood for the defendants. On the part of the South it was claimed:—That the Fund was the property of those who received the benefit of it; of which they could not be deprived without clear proof of a breach of condition:—That there had been no forfeiture by the separation, because the General Conference, in the exercise of its legitimate authority, and for good and sufficient reasons, had assented to that division. They therefore ask that an equitable proportion of the capital, and of the profits of the Concern since 1845, should be awarded to them. On the part of the North it was claimed:—That the Fund was the property of the Methodist Episcopal Church, the beneficiaries receiving the profits of it merely by way of charity:—That the Southern Conferences seceded from and so form, at the present time, no part of the Church; since the General Conference had no power to authorize a separation; and, in fact, did not authorize it, their action being prospective, and accompanied by conditions which had not been complied with. And even had the separation been legitimate, a division of the property could only be claimed in virtue of a special agreement—sanctioned by a competent court; and there was, moreover, if the action of the General Conference was available, a special agreement as to the property in question, in virtue of which the plaintiffs can have no claim upon it. At the close of the arguments, the Court announced that it would not give its decision for some time; and advised the parties, in the mean while, to make an amicable adjustment of the matter; intimating that such an adjustment, if made, would receive the sanction of the Court. The defendants, therefore, made proposals to the plaintiffs to submit the matter to a legal arbitration, under the sanction of the Court; without, however, conceding any thing as to the question before the Court. The plaintiffs, meanwhile, before this offer was communicated to them, made similar overtures to the defendants. There is, therefore, every reason to hope for an amicable adjustment of this vexatious case.

The General Assembly of the New School Presbyterian Church convened at Utica, May 15. Rev. Albert Barnes of Philadelphia was chosen Moderator by a unanimous vote. The chief topic of interest discussed was a plan for the extension of the distinctive principles of the denomination, especially at the West. A few petitions on the subject of Slavery were presented. They were quietly disposed of by re-affirming the conciliatory action of the preceding General Assembly. Hon. J.R. Giddings, of Ohio, who was elected as a delegate, and was expected to agitate this question, was prevented by an accident from being present. The city of Washington was selected as the place for the next meeting.– The General Assembly of the Old School Presbyterian Church met on the 20th of May at St. Louis. Rev. Dr. Humphreys, of Kentucky, was chosen Moderator. The next meeting of the Assembly was appointed to be held at Charleston, upon the assurance of delegates from South Carolina that there was no danger of that city being at that time situated in a foreign country.

The question as to the comparative speed of the British and American Ocean Steamers has been settled for the present. The Pacific, of Collins's line, has made the four shortest passages, three of them consecutive, that have been made across the Atlantic. They were all performed within ten days, which has not been accomplished by any British steamer. The American Ocean Steamers now afloat number 74, with an aggregate tonnage of nearly 90,000. Of these, 9 ships, averaging about 2400 tons, cross the Atlantic; 25 vessels, averaging 1250 tons, ply between ports on the Atlantic and on the Gulf of Mexico; and 40 steamers, averaging 650 tons, are employed on the Pacific.

During the month of May 38,858 immigrants arrived at the port of New York. The arrivals in five months of the present year were 100,571, exceeding by 21,169 those of the corresponding period last year. The English and Irish papers announce the expected departure of increasing numbers of emigrants, of the most desirable class; to make amends for which, the local authorities are emptying the poor-houses upon our shores; it being found cheaper to export than to feed their paupers. This will be done, unless prevented, more extensively this year than ever before.

The Legislature of New York convened in Special Session on the 10th of June. In the House Hon. J.B. Varnum of New York City was chosen Speaker, in place of Mr. Raymond, who is in Europe, and the organization was continued in other respects as before the adjournment. The twelve Senators who resigned in order to prevent the passage of the bill for the Enlargement of the Canals, were, with a single exception, nominated for re-election. The result of the special election was, that of the twelve vacancies, five were filled with advocates, and seven with opponents of the proposed measure; and in one district there was no choice. The Senate therefore stands at present twenty-two in favor, and nine opposed to the bill. The Message of Governor Hunt narrates the events which gave occasion to the Extra Session, and argues in favor of the constitutionality and expediency of the proposed measure for the enlargement of the canals.– An Address has been issued by 56 of the 112 members of the Convention which framed the Constitution of the State, whose names are appended to that document, in which, after examining the provisions of the Constitution, and of the proposed Enlargement Bill, they express it as their opinion that the bill violates the entire spirit and scope of the financial article of the Constitution, and is inconsistent with several of its express provisions.

A large number of Germans who had assembled at Hoboken, opposite to New York, on the 26th of May, to celebrate their customary May-Festival, were attacked by a gang of desperadoes from New York, known as "Short Boys." The Germans repulsed their assailants, and made violent reprisals. In the course of the riot great damage was done to property, and one person lost his life, besides many being severely injured.

The Legislature of Massachusetts closed a very protracted session on the 24th of May. Among the measures passed, was a General Banking Act; a Homestead Exemption Law, with a limit of $500; the Secret Ballot Law, requiring all ballots to be inclosed in envelopes; a law to take the sense of the people whether a Convention shall be called to revise the Constitution of the State; a law changing the composition of the Board of Overseers of Harvard University; the Plurality Act, in accordance with which members of Congress at the second trial, and Presidential electors at the first, are elected by a plurality of votes. At the special election to supply three vacancies in the Congressional representation, Mr. Rantoul, Free-Soil Democrat, and Messrs. Thompson and Goodrich, Whigs, received a plurality, and were elected. Mr. Sumner has addressed to the Legislature a letter, accepting the office of United States Senator. He says that he will maintain the interests of all parts of the country, and oppose every effort to loosen the ties of the Union, as well as "all sectionalism, whether it appear in unconstitutional efforts by the North to carry freedom to the Slave States, or in unconstitutional efforts of the South, aided by Northern allies, to carry the sectional evil of slavery into the Free States; or in whatsoever efforts it may make to extend the sectional dominion of slavery over the United States." He looks upon the Union as the guardian of the repose of the States, and as the model of a future federation among nations; and he does not believe that any part of it can be permanently separated from the rest. Politics, he says, are simply morals applied to public affairs; and his political course shall be determined by those everlasting rules of right and wrong, which are a law alike to individuals and communities. An address from 170 members of the late Legislature has been published, denouncing, in the severest terms, the political combination which resulted in the election of the present Governor and Senator. The Supreme Court have pronounced a unanimous opinion, affirming the constitutionality of the Fugitive Slave law. Several persons charged with aiding in the escape of Shadrach, the fugitive, have been tried; but the jury were unable to agree upon a verdict.