полная версия

полная версияHarper's New Monthly Magazine, Vol. 3, July, 1851

West paused abruptly, for the singular expression of the young lady's features filled him with astonishment.

"You do not know, then—" she began.

"Know what?"

"That I—am a—a natural child!" she completed, with, a crimson blush, turning away her head as she spoke, and covering her face with her hands—"that I am without fortune or relations; that my father died intestate; that the heir-at-law, who lives abroad, and without whose permission nothing can be done—moreover, who is said to be a heartless spendthrift—will take all my father leaves; that I have but one more week given me to vacate this house by the landlord; in short, that I must work if I would not starve: that, in a word, I am a beggar!" And the poor girl sobbed convulsively; while Bernard West, on whom this speech acted as some terrible hurricane upon the trees of a tropical forest, tearing up, as it were, by the roots, all the terrible stoicism of his nature, and rousing hopes and dreams which he had long banished to the deepest and most hopeless abysses of his soul; while Bernard, we repeat, ventured to take her hand in his own, and calm her painful agitation by such suggestions as immediately occurred to his mind.

"In the first place," he said, "my dear Miss Brace, I come to repay to you your father's generous gift."

"It belongs to his legal heirs. I can not receive it with honor," said the money-lender's daughter, firmly.

"Not so," replied West, gravely: "it was a free gift to me. I repay it by a natural, not a legal obligation;" and he laid the two twenty-pound notes upon the table. "Next," he resumed, "I have to pay a debt of gratitude. I owe my life to your father. Thus in a manner I have become his adopted son. Thus," he continued impetuously, "I have a right to say to you, regard me as a brother; share the produce of my labor; render me happy in the thought that I am serving the child of my benefactor! To disdain my gratitude would be a cruel insult."

"I can not disdain it!" exclaimed the daughter of the usurer with a sudden impulse of that sublime confidence which a noble and generous soul can alone inspire. "Yes—I accept your assistance!"

The face of Bernard brightened up, as if by an electric agent. But how were the two children of sorrow confounded by the discovery that they were no longer alone, and that their conversation had been overheard by an utter stranger, who, leaning against the wall at the further end of the room, near the door, appeared to survey them with an utter indifference to the propriety of such behavior!

He was a man of between forty and fifty years; a great beard and mustache concealed the lower part of a swarthy but handsome countenance of rare dignity and severity of outline. His dress was utterly un-English. A vast mantle, with a hood, fell nearly to the ground, and he wore huge courier's boots, which were still splashed, as if from a journey. His great dark eyes rested with an expression of royal benevolence upon the two young people, toward whom he had advanced with a courteous inclination, that, as if magnetically, repressed Bernard's first indignant impulse.

"I am the heir-at-law," he said, in a mild voice, as if he had been announcing a most agreeable piece of intelligence.

"Then, sir," said Bernard, "I trust—"

"Trust absolutely!" interrupted quickly the foreign-looking heir. "My children, do you know who I am? No? I will tell you. I am a monster, who in his youth preferred beauty to ambition, and glory to gold. For ten years after attaining manhood I struggled on, an outcast from my family, in poverty and humiliation, without friends, and often without bread. At the end of five more years I was a great man, and those who had neglected, and starved, and scorned me, came to bow down and worship. But the beauty I had adored was dust, and the fire of youthful hope quenched in the bitter waters of science. For ten years since I have wandered over the earth. I am rich; I may say my wealth is boundless; for I have but to shake a few fancies from this brain, to trace a few ciphers with this hand, and they become gold at my command. Yet, mark my words, my children! One look of love is, in my esteem, worth more than all the applause of an age, or all the wealth of an empire!" The dark stranger paused for an instant, as if in meditation, then abruptly continued: "I take your inheritance, fair child!—I rob the orphan and the fatherless!"—and the smile of disdainful pride which followed these words said more than whole piles of parchment renunciations as to his intention.

Involuntarily the orphan and Bernard seized each a hand of the mysterious man beside them, who, silently drawing the two hands together, and uniting them in his own, said, gently, "Love one another as you will, my young friends, yet spare at times a kind thought for the old wandering poet! Not a word! I understand you, though you do not understand yourselves. It is as easy to tell a fortune as to give it."

And was the prophecy realized? asks a curious reader. But no answer is needed; for if the prophecy were false, why record it? And, pray, who was the stranger, after all? Too curious reader!—it is one thing to tell stories, and another to commit breaches of confidence.

A FRENCHMAN IN LONDON

BY JULES DE PREMARYONE of the principal causes of surprise to me in walking along the streets of London, has been to see myself all at once become a curious animal. I did not think that I had any of the qualities necessary for such a thing, being neither humpbacked nor clubfooted, neither a giant nor a dwarf. Thus, when on the day of my arrival I went along Regent-street, and heard the exclamations and laughter of the crowd on seeing me, I examined myself from head to foot, to ascertain the cause of the unhoped-for success which I obtained in England. I even felt all up my back, thinking that perhaps some facetious boy might have transformed me into a walking placard. There was nothing, however; but I had mustaches and a foreign air! A foreign air! That is one of the little miseries on which you do not count, oh, simple and inexperienced travelers!

At home you may have the dignity and nobleness of the Cid—you may be another Talma: but pass the Channel—show yourself to the English, and in spite of yourself you will become as comic as Arnal. Arnal! do I say? why, he would not make them laugh so much as you do; and they would consider our inimitable comedians, Levassor and Hoffmann, as serious personages. Do not be angry. They would only laugh the more. In this respect the English are wanting in good taste and indulgence. Their astonishment is silly and their mockery puerile. The sight of a pair of mustaches makes them roar with laughter, and they are in an ecstasy of fun at the sight of a rather broad-brimmed hat. A people must be very much bored to seize such occasions of amusing themselves. However, all the travers, like all the qualities of the English, arise from the national spirit carried to exaggeration. They consider themselves the beau ideal of human kind. Their stiffness of bearing, their pale faces, their hair, their whiskers cut into the shape of mutton chops, the excessive height of their shirt collars, and the inelegant cut of their coats—all that makes them as proud as Trafalgar and Waterloo.

In our theatres we laugh at them as they laugh at us; and on that score we are quits. But in our great towns they are much better and more seriously received than we Frenchmen are in England.

At Paris nowadays nobody laughs at an Englishman; but at London every body laughs at a Frenchman. We do not make this remark from any feeling of ill-will; in fact, we think that to cause a smile on the thin and pinched-up lips of old England is not a small triumph for our beards and mustaches. After all, too, the astonishment which the Englishman manifests at the sight of a newly disembarked Frenchman (an astonishment which appears singular when we call to mind the frequent communications between the two nations), is less inexplicable than may be thought. Geographically speaking, France and England touch each other; morally, they are at an immeasurable distance. Nothing is done at Calais as at Dover, nothing at London as at Paris. There is as much difference between the two races as between white and black. In France, the Englishman conforms willingly to our customs, and quickly adopts our manner of acting; but in England we are like a stain on a harmonious picture.

Our fashion of sauntering along the streets, smiling at the pretty girls we meet, looking at the shops, or stopping to chat with a friend, fills the English with stupefaction. They always walk straight before them like mad dogs. In conversation there is the same difference. In England, it is always solemn. Left alone after dinner, the men adopt a subject of conversation, which never varies during all the rest of the evening. Each one is allowed to develop his argument without interruption. Perhaps he is not understood, but he is listened to. When he has ended, it becomes the turn of another, who is heard with the same respect. The thing resembles a quiet sitting of the parliament. But in France, conversation is a veritable mêlée; it is the contrary excess. A subject is left and taken up twenty times, amidst joyous and unforeseen interruptions. We throw words at each other's heads without doing ourselves any harm; smart sallies break forth, and bons mots roll under the table. In short, the Englishman reflects before speaking; the Frenchman speaks first and reflects afterward—if he has time. The Frenchman converses, the Englishman talks: and it is the same with respect to pleasure. Place a Frenchman, who feels ennui, by the side of an Englishman who amuses himself, and it will be the former who will have the gayest air. From love the Englishman only demands its brutal joys; whereas the Frenchman pays court to a woman. The Englishman, at table, drinks to repletion; the Frenchman never exceeds intoxication.

A difference equally striking exists between the females of the two countries. I do not now speak of the beauty of the type of the one, or the elegance and good taste of the others; but I will notice one or two great contrasts. In France a young girl is reserved, is timid, and, as it were, hidden under the shade of the family: but the married woman has every liberty, and many husbands can tell you that she does not always use it with extreme moderation! In England you are surprised at the confident bearing of young girls, and the chaste reserve of married women. The former not only willingly listen to gallant compliments, but even excite them; while the latter, by the simple propriety of their bearing, impose on the boldest.

The boldness of young girls in England was explained to me, by the great emigration of young men—in other words, by the scarcity of husbands. The French girl who wants a husband is ordinarily rather disdainful; the English girl is by no means difficult.

A Frenchwoman walks negligently leaning on our arm, and we regulate our steps by the timidity and uncertainty of hers; the Englishwoman walks with the head erect, and takes large strides like a soldier charging. An accident made me acquainted with the secret of the strange way of walking which Englishwomen have. I was lately on a visit to the family of a merchant, whose three daughters are receiving a costly education. The French master, the drawing master, and the music master, had each given his lesson, when I saw a sergeant of the Grenadiers of the Guard arrive. He went into the garden, and was followed by the young ladies.

"Ah! mon Dieu!" I cried to the father; "these young ladies are surely not going to learn the military exercise!"

"No," said he, with a smile.

"What, then, has this professor in a red coat come for?"

"He is the master of grace!"

"What! that grenadier who is as long as the column in Trafalgar-square?"

"Yes, or rather he is the walking master."

I looked out of the window and saw the three young ladies drawn up and immovable as soldiers, and presently they began to march to the step of the grenadier. They formed a charming platoon, and trod the military step with a precision worthy of admiration. I asked for an explanation of such a strange thing.

"We, in England," said my host, "understand better the duty of women than you Frenchmen do. We can not regulate our manner of walking on that of a being subjected to us. Our dignity forbids it. It is the woman's duty to follow us; consequently she must walk as we do—we can't walk as she does."

"Ma foi!" said I, "I must admit that in progress you are decidedly our masters. In France the law, it is true, commands the wife to follow her husband; but it does not, I confess, say that she must do so at the rate of quick march!"

The contrasts between the two countries are in truth inexhaustible. Indeed I defy the most patient observer to find any point of resemblance between them. In France, houses are gay in appearance; in London, with the exception of some streets in the centre, such as Regent-street or Oxford-street, they are as dark and dismal as prisons. Our windows open from the left to the right; windows in England open from top to bottom. At Paris, to ring or knock too loud is vulgar and ill-bred; at London, if you don't execute a tattoo with the knocker or a symphony with the bell, you are considered a poor wretch, and are left an hour at the door. Our hack cabs take their stand on one side of the street; in England they occupy the middle. Our coachmen get up in front of their vehicles; in England they go behind. In Paris Englishmen are charming; at home they are—Englishmen. One thing astonishes me greatly—that the English don't walk on their hands, since we walk on our feet.

I do not know from experience the Scottish hospitality which M. Scribe has lauded in one of his vaudevilles. But I know what to think of that of the county of Middlesex capital—London. Here I can assure you it is never given, but always sold. London is the town of closed doors. You feel yourself more a foreigner here than in any other country. On strolling along the spacious squares and magnificent streets in which civilization displays all its marvels, you seek in vain for some fissure by which to introduce yourself into English society, which is thickly steeped in individualism. With letters of recommendation, if of high authority, you may, it is true, gain access to a family of the middle class; and, once received, you will be well treated. But what conditions you must fulfill to gain that! You must lead a life like that of the cloister, and sacrifice all your dearest habits. The Englishman, though he invented the word eccentric, does not tolerate eccentricity in a foreigner. And, on the whole, the bourgeoise hospitality is not worth the sacrifices it costs.

We must not, however, be angry with the English for being so little communicative with foreigners, since they scarcely communicate among themselves. The extent of distances and the fatigue of serious affairs are the principal causes of this. It is almost only in the evening you can visit them, and in the evening they are overwhelmed with fatigue. Besides this, all the usages of the English show that they are not naturally sociable. The cellular system of taverns, in which every person is confined in a sort of box without a lid; the silent clubs, in which some write while others read the papers, and only interrupt themselves to make a sign of "good evening" with the hand—all that sort of thing constitutes an existence which the French have the irreverence to call selfish.

Among the high aristocracy, hospitality is a great and noble thing; but it is more accessible to the wealthy tallow chandler than to a writer or an artist of genius. In England, with the exception of Dickens and Bulwer, the literary man is less considered than the comedian was in France a century ago. In France, it is admirable to witness the fusion of the aristocracies of family, money, and intelligence. Artists and poets are invited to all the fêtes of high society. As soon as a writer has raised himself somewhat above the vulgar, he perceives that the great ones of this world occupy themselves with him, show him protection and sympathy. But what is a man of intelligence here in London? He is an animal less considered than the lowest coal-dealer in the city. And what is the consequence of this neglect of arts and literature? That England is almost reduced to the necessity of robbing our artists and writers. The theatres in particular pirate from us with unexampled effrontery.

But to return to the want of hospitality of the English to the foreign bards who have come over to sing the marvels of the Great Exhibition. You may meet in London at this moment a dozen literary phantoms who drag the shroud of their ennui and discouragement along Piccadilly. These shadows, when they recognize each other, shake hands and relate their disappointments. They are French journalists. Separated one from the other, and not knowing on what chord of their lyres to celebrate the virtues of a people who laugh in their faces, and who seem to be ignorant of the men whose names are most known and admired at Paris, these French journalists ask each other the same question—"Do you amuse yourself at London?" And they all make the same reply, "I am bored at the rate of twenty shillings a day!" To which they all exclaim in chorus, "That's very dear!"

A year ago, when the Friends of Peace, those generous Utopian dreamers, came to London, they were received at the station by the most celebrated English economists, carried in triumph to the residences prepared for them, taken to visit all that is curious in England—in a word, treated as princes. But then they were the friends of the great Cobden! whereas England cares not a straw for the mob of simple literary men, writers of imagination! She would not even send their confrères to bid them welcome. Let them manage them as they can; let them lodge in bad hotels, and dine ill; let them content themselves with seeing London on the outside, for neither the docks of the Thames nor the museums of the great nobles will be opened to them!

But what matters, after all, that we are at London without any guides but ourselves? My opinion is, that we must put a good face on it, and see the marvels of the monster town in spite of itself.

LONDON SPARROWS

BY CHARLES DICKENSHOW extremely plain—not to say ugly—street-children often are! Their hard life and the characters of their parents, cause it. This child, who is now staring in at the window upon a print of Sir Robert Peel, and flattening his nose against the glass, has a forehead "villainous low," with dark eyes, and short dark hair, and his diminutive face, both in features and expression, is uncommonly like one end of a cocoa-nut. What a sad lot for these children to be left thus—perhaps even turned adrift by their parents, to wander about the streets, and pick up, here and there, a precarious crumb! And now, as I turn round, I see three others, apparently in the same wretched outcast condition—two boys and a girl. The elder boy seems not to care much about it; he has, no doubt, become more accustomed to his lot. He is between twelve and thirteen. His voice is hoarse, cracked, and discordant; perhaps by some street-cry. He has a large projecting nose, red pulpy lips, a long chin, and a long throat, uncovered. No collar—indeed, now, I look again, no shirt! and he wears a greasy jacket and trowsers, both much too small for him; so that his large red hands and wrists swollen with chilblains hang listlessly far below the end of his sleeves; and his long, thin ankles, and large unshapely feet are so far below the end of his trowsers, as to give the appearance of the legs and feet of a bird. He is whistling a sort of jig tune, and beating time with one of his heels. Poor boy!—I dare say he would be very glad to work if he had an opportunity. A girl, of about twelve, stands on one side of him. She is so scantily clad as to be scarcely decent. Her shoulder-blades stick up, she is so meagre, and she shivers with the cold. But I do not like the expression of her face; for, though I pity her eager, hungry look, and evidently bad state of health, I can not help seeing that she has very much the look of a sickly rat. On the other side of the elder boy, stands a younger one—of some ten years of age. He is very pale, and has fair hair, a rueful mouth, rather dropping at the corners, large sad eyes, with very long lashes, and an expression at once timid yet indifferent—innocent and guilty. Guilty?—of what can such a child be guilty? They slowly walk away, all three—perhaps in consequence of my observing them so attentively. They quicken their pace as they turn the corner. Why was I so tardy to relieve them? It would have become me, as a Christian, to have thought of relieving their necessities, even for the night, far better than to have speculated upon their physiognomies as a philosopher. But it is time for me to return home. Sad addition to my experience. My wife waiting tea for—bless my so—where? it can't be? yes, it can—my watch is gone! Slipt down through my pocket—no doubt—there's a hole in it—no—or it fell out while I was stooping to fasten my gaiter button in Pall Mall. Most vexatious. A family watch! Gold chain and seals, too! Well—it can't be helped. In these cases a pinch of snuff often—often—pshaw!—often relieves—relieves one—hillo! have I been relieved of that, also! Perhaps it's in my side pocket, with my purse—purse! why, my purse is gone; I really begin to think I must have been robbed!

CONCERNING THE ECLIPSES IN THE MONTH OF JULY, 1851

BY CHARLES COLBYIN the month of July, 1851, there will occur two eclipses; one of the moon and one of the sun.

The former will occur after midnight, Sunday morning, July 13th; and the latter on the morning of Monday, July 28th.

Unless clouds prevent, both will be visible throughout the United States; and if visible will (the solar eclipse especially) attract general observation.

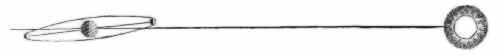

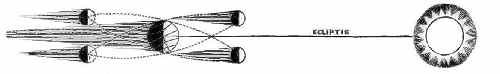

As here represented, there are formed complete shadows, called umbras; and partial shadows, called penumbras.

When an eclipse of the sun occurs, it appears totally eclipsed to those persons who are within the moon's umbra, and partially eclipsed, to those situated within the penumbra.

When an eclipse of the moon occurs, it appears totally eclipsed, if entirely within the earth's umbra, and partially eclipsed, if partially within it.

The length of the moon's umbra is usually greater than the distance of the moon from the earth.

The moon, therefore, crosses the sun's path twice in each revolution.

If, at new moon, it always crossed exactly in that part where the sun is, there would evidently be an eclipse of the sun; and it would recross in the opposite part and pass through the earth's umbra.

But the moon does not always cross the ecliptic where the sun is, nor uniformly in the same part.

Its crossing-place is different at each succeeding revolution.

Since the limits of this article will not allow an extended explanation of the manner of mathematically predicting eclipses, we will apply the foregoing statements in showing that there will occur an eclipse of the sun in July, 1851.

The first diagram on page 240 represents the relative positions of the sun and moon at the time of new moon in June, July, and August, 1851, calculated for Greenwich.

It is probable that there will be but few among the millions who may thus behold these wonderful phenomena who will not understand their causes.

However, an article explaining the manner of predicting these eclipses with diagrams illustrating the path of the moon's shadow in the solar eclipse across the United States and upon the whole earth, may not be acceptable.

Since the earth and moon are solid opaque bodies, they intercept the light passing from the sun through the heavens; or, in other words, they cause the existence of shadows.