полная версия

полная версияBabylonians and Assyrians, Life and Customs

Occasionally the primitive custom was retained of paying the rent in kind instead of in coin. We even hear of “six overcoats” being taken in lieu of rent. The rent of a house might also take the place of interest upon a loan, and the property be handed over to the creditor as security for a debt. Thus in the second and last year of the reign of Evil-Merodach (560 B.C.), and on the fourth of the month Ab, the following agreement was drawn up at Babylon: “Four manehs of silver belonging to Nadin-akhi, the son of Nur-Ea, the son of Masdukku, received from Sapik-zeri, the son of Merodach-nazir, the son of Liu-Merodach. The house of Sapik-zeri, which is in the street Khuburru, and adjoins the houses of Rimut-Bel, the son of Zeriya, the son of the Egyptian, and of Zeriya, the son of Bel-edheru, shall be handed over as security to Nadin-akhi. No rent shall be paid for it, and no interest demanded for the debt. Sapik-zeri shall have it for three years. He must renew the fences and repair all injuries to the walls. At the end of the three years Sapik-zeri shall repay the money—namely, four manehs—to Nadin-akhi, and the latter shall vacate the house. The rent of the warehouse of the eunuch is included, of which Sapik-zeri enjoys the use. Whatever doors Nadin-akhi may have added to the house during his tenancy he shall take away.” Then come the names of three witnesses, one of them being the brother of the creditor, as well as of the clerk who drew up the document.

A few years later, in the fifth year of Nabonidos (551 B.C.), we find the heir-apparent, Belshazzar, receiving house-property on similar terms. “The house of Nebo-akhi-iddin, the son of Sula, the son of Egibi,” we read, “which adjoins the house of Bel-iddin, the son of Birrut, the son of the life-guardsman, is handed over for three years as security for a loan of 1½ manehs to Nebo-kin-akhi, the agent of Belshazzar, the son of the king, on the following conditions: no rent shall be paid for the house, and no interest paid on the debt. The tenant shall renew the fences and make good all dilapidations. At the end of three years the 1½ manehs shall be paid by Nebo-akhi-iddin to Nebo-kin-akhi, and Nebo-kin-akhi shall vacate the house of Nebo-akhi-iddin. Witnessed by Kab-tiya, the son of Talnea, the son of Egibi; by Sapik-zeri, the son of Nergal-yukin, the son of Sin-karab-seme; by Nebo-zer-ibni, the son of Ardia, and the clerk, Bel-akhi-iqisa, the son of Nebo-balasu-ikbi, at Babylon, the 21st day of Nisam (March) and the fifth year of Nabonidos, King of Babylon.”

This was not the only transaction of the kind in which Belshazzar appears, though it is true that his business was carried on by means of agents. Six years later we have another contract relating to his commercial dealings which has already been quoted above. It illustrates the intensely commercial spirit of the Babylonians, and we may form some idea of the high estimation in which trade was held when we see the eldest son of the reigning King acting as a wool merchant and carrying on business like an ordinary merchant.

An interesting document, drawn up in Babylonia in the eleventh year of Sargon (710 B.C.), shortly after the overthrow of Merodach-Baladan, contains an account of a lawsuit which resulted from the purchase of two “ruined houses” in Dur-ilu, a town on the frontier of Elam. They had been purchased by a certain Nebo-liu for 85 shekels, with the intention of pulling them down and erecting new buildings on the site. In order to pay the purchase money Nebo-liu demanded back from “Bel-usatu, the son of Ipunu,” the sum of 30 shekels which he claimed to have lent him. Bel-usatu at first denied the claim, and the matter was brought into court. There judgment was given in favor of the plaintiff, and the defendant was ordered to pay him 45 shekels, 15, or half the amount claimed, being for “costs.” Thereupon Bel-usatu proposed:

“ ‘Instead of the money, take my houses, which are in the town of Der.’ The title-deeds of these houses, the longer side of which was bounded to the east by the house of Bea, the son of Sulâ, and to the west by the entrance to a field which partly belonged to the property, while the shorter side was bounded to the north by the house of Ittabsi, and to the south by the house of Likimmâ, were signed and sealed by Nebo-usatu, who pledged himself not to retract the deed or make any subsequent claim, and they were then handed over to Nebo-liu.” The troubles of the latter, however, were not yet at an end. “Ilu-rabu-bel-sanât, Sennacherib, and Labasu, the sons of Rakhaz the [priest] of the great god, said to Nebo-liu: ‘Seventy-three shekels of your money you have received from our father. Give us, therefore, 50 shekels and we will deliver to you the house and its garden which belonged to our father.’ The house, which was fit only to be pulled down and rebuilt, along with a grove of forty date-bearing palms, was situated on the bank of the canal of Dûtu in Dur-ilu, its longer side adjoining on the north the house of Edheru, the son of Baniya, the priest of Â, and on the south the canal of Dûtu, while its shorter side was bounded on the east by the house of Nergal-epus, and on the west by the street Mutaqutu. Nebo-liu agreed, and looked out and gave Rakhaz and his sons 50 shekels of silver, together with an overcoat and two shekels by way of a bakshish to bind the bargain, the whole amounting to 52 shekels, paid in full.” The custom of adding a bakshish or “present” to the purchase-money at the conclusion of a bargain is still characteristic of the East. Other examples of it are met with in the Babylonian contracts, and prove how immemorially old it is. Thus in the second year of Darius, when the three sons of a “smith” sold a house near the Gate of Zamama, at Babylon, to the grandson of another “smith,” besides the purchase money for the house, which amounted to 67½ shekels, the buyer gave in addition a bakshish of 2½ shekels (7s. 6d.) as well as “a dress for the lady of the house.” Three shekels were further given as “a present” for sealing the deed. So too, the negotiations for the sale of some land in the second year of Evil-Merodach were accompanied by a bakshish of 5 shekels.

Lawsuits connected with the sale or lease of houses do not seem to have been uncommon. One of the documents which have come down to us from the ancient records of Babylon is a list of “the judges before whom Sapik-zeri, the son of Zirutu, and Baladhu, the son of Nasikatum, the slave of the secretary for the Marshlands,” were called upon to appear in a suit relating to “the house and deed which Zirutu, the father of Sapik-zeri, had sealed and given to Baladhu,” who had afterward handed both of them over to Sapik-zeri. Among the judges we find the governor of the Marshlands, who acted as president, the sub-governor, the mayor of Erech, the priest of Ur, and one of the governors of the district “beyond” the Euphrates. The list is dated the 6th of Nisan or March, in the seventeenth year of Nebuchadnezzar.

The value of land was proportionate to that of house-property. In the early days of Babylonia its value was fixed by the amount of grain that could be grown upon it, and it was accordingly in grain that the owner was paid by the purchaser or lessee. Gradually, however, a metal currency took the place of the grain, and in the later age of Babylonian history even the rent was but rarely paid in kind. We learn from a lawsuit decided in the reign of Samsu-iluna, the son of Khammurabi, that it was customary for an estate to be “paced round” by the rabianum or “magistrates” of the city. The ceremony was equivalent to “beating the bounds” of a parish in modern England, and it is probable that it was performed every year. Such at least is the custom in Egypt, where the limits of a piece of property are measured and fixed annually. The Babylonian document in which the custom is referred to relates to a dispute about a plantation of acacias which grew in the neighborhood of the modern Tel Sifr. The magistrates, before whom it was brought, are described as looking after not only the city but also “the walls and streets,” from which we may gather that municipal commissioners already existed in the Babylonian towns. The plaintiff made oath before them over the copper libation-bowl of the god of Boundaries, which thus took the place of the Bible in an English court of law.

A few years later, in the reign of Ammi-zadok, three men rented a field for three years on terms of partnership, agreeing to give the owner during the first two years 1 gur of grain upon each feddan or acre. The whole of the third harvest was to go to the lessees, and the partners were to divide the crop in equal shares “on the day of the harvest.”

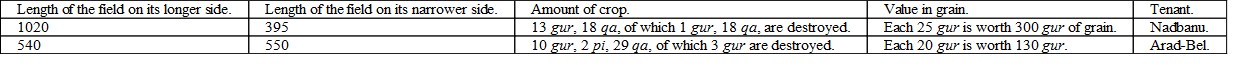

When we come to the twelfth century B.C., however, the maneh and shekel have been substituted for the crops of the field. Thus we hear of 704 shekels and a fraction being paid for a field which was calculated to produce 3 gur of corn, and of 110 shekels being given for another estate which contained a grove of date-palms and on which 2 gur of grain were sown. How much grain could be grown on a piece of land we can gather from the official reports of the cadastral survey. In the sixth year of Cyrus, for example, the following report was drawn up of the “measurement of a corn-field and of the corn in the ear” belonging to a Babylonian taxpayer:

The cadastral survey for purposes of taxation went back to an early period of Babylonian history. It was already at work in the age of Sargon of Akkad. The survey of the district or principality of Lagas (now Tello) which was drawn up in that remote epoch of history is in our hands, and is interesting on account of its reference to a “governor” of the land of the Amorites, or Canaan, who bears the Canaanitish name of Urimelech. The survey states that the district in question contained 39,694 acres, 1,325 sar, as well as 17 large towns and 8 subdivisions.

Another cadastral survey from Lagas, but of the period of Khammurabi, which has recently been published by Dr. Scheil, tells us that the towns on the lower banks of “the canal of Lagas” had to pay the treasury each year 35⅚ shekels of silver according to the assessment of the tax-collector Sin-mustal. One of the towns was that of the Aramean tribe of Pekod. Another is called the town of the Brewers, and another is described as “the Copper-Foundry.” Most of the towns were assessed at half a shekel, though there were some which had to pay a shekel and more. Among the latter was the town of Ninâ, which gave its name to the more famous Nineveh on the Tigris. The surveyor, it should be added, was an important personage in Babylonian society, and the contract tablets of the second Babylonian empire not unfrequently mention him.

Assyria, like Babylonia, has yielded us a good many deeds relating to the sale and lease of houses and landed estate. We can estimate from them the average value of house-property in Nineveh in the time of the second Assyrian empire, when the wealth of the Eastern world was being poured into it and the Assyrian kings were striving to divert the trade of Phœnicia into their own hands. Thus, in 694 B.C., a house with two doors was sold for 3 manehs 20 shekels, and two years subsequently another which adjoined it was purchased for 1 maneh “according to the royal standard.” The contract for the sale is a good example of what an Assyrian deed of sale in such a case was like. “The nail-marks of Sar-ludari, Akhassuru, and Amat-Suhla, the wife of Bel-suri, the official, the son of the priest, and owner of the house which is sold. The house, which is in thorough repair, with its woodwork, doors, and court, situated in the city of Nineveh and adjoining the houses of Mannu-ki-akhi and Ilu-ittiya and the street Sipru, has been negotiated for by Zil-Assur, the Egyptian secretary. He has bought it for 1 maneh of silver according to the royal standard from Sar-ludari, Akhassuru, and Amat-Suhla, the wife of Bel-duri. The money has been paid in full, and the house received as bought. Withdrawal from the contract, lawsuits, and claims are hereby excluded. Whoever hereafter at any time, whether these men or others, shall bring an action and claims against Zil-Assur, shall be fined 10 manehs of silver. Witnessed by Susanqu-khatna-nis, Murmaza the official, Rasuh the sailor, Nebo-dur-uzur the champion, Murmaza the naval captain, Sin-sar-uzur, and Zidqa (Zedekiah). The sixteenth of Sivan during the year of office of Zaza, the governor of Arpad (692 B.C.).” It is noticeable that the first witness has a Syrian name.

One of the characteristics of the Assyrian deeds is that so few of the parties who appear in them are able to write their names. Nail-marks take the place of seals even in the case of persons who hold official positions and who are shown by the contracts to have been men of property. In this respect Assyria offers a striking contrast to Babylonia, where “the nail-mark” seldom makes its appearance. Closely connected with this inability to write is the absence of the seal-cylinder, which was part of the ordinary dress of the Babylonian gentleman. In the Assyrian contracts, on the other hand, it is conspicuous by its absence. The use of it in Assyria was an imitation of Babylonian manners, and was confined for the most part to the scribes and higher official class, who had received a literary education.

Land in Assyria was measured by homers rather than by feddans or acres as in Babylonia. In 674 B.C. an estate of 35 homers, in the town of Sairi, was sold for 5 manehs, any infringement of the contract being punished by a fine of 10 manehs of silver or one of gold, to be paid into the treasury of the temple of Istar. We learn incidentally from this that the value of gold to silver at the time was as one to ten. Five years previously 6 homers of land in another small Assyrian town had been let at an annual rent of 1 maneh of silver “according to the standard of Carchemish.” In the reign of Assur-bani-pal a homer of corn-land was rented for six years for 10 shekels a year. The land was calculated to produce 9 qas of grain, and at the end of the first three years it was stipulated that there should be a rotation of crops. About the same time two fields, enclosing an area of 3⅔ homers, were leased by a certain Rimu-ana-Bel of Beth-Abimelech, whose father's name, Yatanael, shows that he was of Syrian origin. The steward of “the son of a king” took them for six years at an annual rent of 12 shekels. One of the fields contained a well, and yielded 15 qas of grain to each homer. It is stated in the contract that the fields had no mortgage upon them, and that the lessee had a right to the whole of the crop which they produced.

It was not in Assyria only that plots of ground could be leased and sold in accordance with the provisions of Assyrian law. Conquest had brought landed property into the hands of Assyrians in other parts of the Eastern world, and it could be put up to auction at Nineveh, where the proprietors lived. About 660 B.C., for instance, a considerable estate was thus sold in the oasis of Singara, in the centre of Mesopotamia. It lay within the precincts of the temple of Istar, and contained a grove of 1,000 young palms. It included, moreover, a field of 2 homers planted with terebinths, house-property extending over 6 homers, a house with a corn-field attached to it, and another house which stood in the grove of Yarkhu, the Moon-god. The whole was sold for 4 shekels of silver “according to the standard of Carchemish,” and the penalty for any infringement of the contract was again to be the payment of a maneh of gold (£90) to the treasury of the goddess Istar. When one of the parties to the contract was of Aramean descent, it was usual to add an explanatory docket in Aramaic to the deed of sale. Indeed, this seems to have been sometimes done even where there were no Arameans in the case, so thoroughly had Aramaic become the common language of trade. Thus in the year of Sennacherib's office as eponym (687 B.C.) we hear of the sale of three shops in Nineveh on the part of a certain Dain-kurban, whose name is written in Aramaic letters on the outer envelope of the deed of sale. Thirty shekels were paid for them, and a fine of 10 manehs imposed upon anyone who should attempt to invalidate the sale. The shops seem to have been situated in the Syrian quarter of the city, as we are told that they were opposite the tenement of Nakharau, “the man of Nahor.”

It will have been noticed how frequently it is stated that a “plantation” or grove of palms is attached to the house or field which is rented and sold. In Babylonia, in fact, an estate was not considered complete without its garden, which almost invariably included a clump of palms. The date-palm was the staple of the country. It was almost the only tree which grew there, and it grew in marvellous abundance. Stem, leaves, and fruit were all alike turned to use. The columns and roofing-beams of the temples and houses were made of its stem, which was also employed for bonding the brick walls of the cities. Its fibres were twisted into ropes, its leaves woven into baskets. The fruit it bore was utilized in many ways. Sometimes the dates were eaten fresh, at other times they were dried and exported to foreign lands; out of some of them wine was made, out of others a rich and luscious sugar. It was little wonder that the Babylonian regarded the palm as the best gift that Nature had bestowed upon him. Palm-land necessarily fetched a higher price than corn-land, and we may conclude, from a contract of the third year of Cyrus, that its valuation was seven and one-half times greater.

Trade partnerships were common, and even commercial companies were not unknown. The great banking and money-lending firm which was known in Babylonia under the name of its founder, Egibi, and from which so many of the contract-tablets have been derived, was an example of the latter. It lasted through several generations and seems to have been but little affected by the political revolutions and changes which took place at Babylon. It saw the rise and fall of the empire of Nebuchadnezzar, and flourished quite as much under the Persian as under the native kings.

As far back as the reign of Samsu-iluna we find women entering into partnership with men for business purposes on a footing of absolute equality. A certain Amat-Samas, for instance, a devotee of the Sun-god, did so with two men in order to trade with a maneh of silver which had been borrowed from the treasury of the god. It was stipulated in the deed which was indentured when the partnership was made that in case of disagreement the capital and interest accruing from it were to be divided in equal shares among the three partners.

In the later Babylonian period the contract was drawn up in much the same form, though with a little more detail. In the report of a trial dated the eighth day of Sebat or January, in the eighteenth year of Nebuchadnezzar II., we have the following reference to one that had been made twenty-one years before: “A partnership was entered into between Nebo-yukin-abla and his son Nebo-bel-sunu on the one side and Musezib-Bel on the other, which lasted from the eighteenth year of Nabopolassar, King of Babylon, to the eighteenth year of Nebuchadnezzar. The contract was produced before the judge of the judges. Fifty shekels of silver were adjudged to Nebo-bel-sunu and his father Nebo-yukin-abla. No further agreement or partnership exists between the two parties.… They have ended their contract with one another. All former obligations in their names are rescinded.”

One of the latest Babylonian deeds of partnership that have come down to us is dated in the fifth year of Xerxes. It begins with the statement that “Bel-edheru, son of Nergal-edheru and Ribâta, son of Kasmani, have entered into partnership with one another, contributing severally toward it 2½ manehs of silver in stamped shekel-pieces and half a maneh of silver, also in stamped shekel-pieces. Whatever profits Ribâta shall make on the capital—namely, the 3 manehs in stamped shekel-pieces—whether in town or country, [he shall divide with] Bel-edheru proportionally to the share of the latter in the business. When the partnership is dissolved he shall repay to Bel-edheru the [2½] manehs contributed by him. Ribâta, son of Kasmani, undertakes all responsibility for the money.” Then come the names of six witnesses.

Money, however, was not the only subject of a deed of partnership. Houses and other property could be bought and sold and traded with in common. Thus we hear of Itti-Merodach-baladh, the grandson of “the Egyptian,” and Merodach-sapik-zeri starting as partners with a capital of 5 manehs of silver and 130 empty barrels, two slaves acting as agents, and on another occasion we find it stipulated that “200 barrels full of good beer, 20 empty barrels, 10 cups and saucers, 90 gur of dates in the storehouse, 15 gur of chickpease (?), and 14 sheep, besides the profits from the shop and whatever else Bel-sunu has accumulated, shall be shared between him” and his partner.

The partners usually contributed in equal parts to the business, and the profits were divided equally among them. Where this was not the case, provision was made for a proportionate distribution of profit and loss. All profits were included, whether made, to use the language of Babylonian law, “in town or country.” The partnership was generally entered into for a fixed term of years, but could be terminated sooner by death or by agreement. One of the partners could be represented by an agent, who was often a slave; in some instances we hear of the wife taking the place of her husband or other relation during his absence from home. Thus in a deed dated in the second year of Nergal-sharezer (559 B.C.) we read: “As long as Pani-Nebo-dhemi, the brother of Ili-qanua, does not return from his travels, Burasu, the wife of Ili-qanua, shall share in the business of Ili-qanua, in the place of Pani-Nebo-dhemi. When Pani-Nebo-dhemi returns she shall leave Ili-qanua and hand over the share to Pani-Nebo-dhemi.” As one of the witnesses to the document is a “minister of the king” who bears the Syrian name of Salammanu, or Solomon the son of Baal-tammuh, it is possible that Pani-Nebo-dhemi was a Syrian merchant whose business obliged him to reside in a foreign country.

That partnerships in Babylonia were originally made for the sake of foreign trade seems probable from the name given to them. This is kharran, which properly means a “road” or “caravan.” The earliest partners in trade would have been the members of a caravan, who clubbed together to travel and traffic in foreign lands and to defend themselves in common from the perils of the journey.

The products of the Babylonian looms must have been among the first objects which were thus sent abroad. We have already described the extensive industry which brought wealth into Babylonia and made it from the earliest ages the centre of the trade in rugs and tapestries, cloths and clothing. A large part of the industrial population of the country must have been employed in the factories and shops where the woven and embroidered fabrics were produced and made ready for sale. Long lists exist giving the names of the various articles of dress which were thus manufactured. The goodly “Babylonish garment” carried off by Achan from the sack of Jericho was but one of the many which found their way each year to the shores of the Mediterranean.

The trades of the dyer and the fuller flourished by the side of that of the cloth-maker. So, too, did the trade of the tanner, leather being much used and finely worked. The shoes of the Babylonian ladies were famous; and the saddles of the horses were made with elaborate care.

The smith, too, occupied an honorable position. In the earlier period of Babylonian history, gold, silver, copper, and bronze were the metals which he manufactured into arms, utensils, and ornaments. At a later date, however, iron also came to be extensively used, though probably not before the sixteenth century B.C. The use of bronze, moreover, does not seem to go back much beyond the age of Sargon of Akkad; at all events, the oldest metal tools and weapons found at Tello are of copper, without any admixture of tin. Most of the copper came from the mines of the Sinaitic Peninsula, though the metal was also found in Cyprus, to which reference appears to be made in the annals of Sargon. The tin was brought from a much greater distance. Indeed, it would seem that the nearest sources for it—at any rate in sufficient quantities for the bronze of the Oriental world—were India and the Malayan Peninsula on the one hand, and the southern extremity of Cornwall on the other. It is not surprising, therefore, that it should have been rare and expensive, and that consequently it was long before copper was superseded by the harder bronze. Means, however, were found for hardening the copper when it was used, and copper tools were employed to cut even the hardest of stones.