полная версия

полная версияTam o' the Scoots

"Maybe they're trying out some new stunt," said Blackie. "Probably it is a plan of defense—a sort of divisional training—I'll send a report to G. H. Q. I don't like this concentration of circuses in our neighborhood."

Now a "circus" is a strong squadron of German airplanes attached to no particular army, but employed on those sectors where its activities will be of most value at a critical time; and its appearance is invariably a cause for rejoicing among all red-blooded adventurers.

Two days after Blackie had made his report, von Bissing's World-Renowned Circus was giving a performance, and on this occasion was under royal and imperial patronage.

For, drawn up by the side of the snowy road, some miles in the rear of the line were six big motor-cars, and on a high bank near to the road was a small group of staff officers muffled from chin to heels in long gray overcoats, clumsily belted at the waist.

Aloof from the group was a man of medium height, stoutly built and worn of face, whose expression was one of eager impatience. The face, caricatured a hundred thousand times, was hawklike, the eyes bright and searching, the chin out-thrust. He had a nervous trick of jerking his head sideways as though he were everlastingly suffering from a crick in the neck.

Now and again he raised his glasses to watch the leader as he controlled the evolutions of the twenty-five airplanes which constituted the "circus."

It was a sight well worth watching.

First in a great V, like a flock of wild geese, the squadron swept across the sky, every machine in its station. Then, at a signal from the leader, the V broke into three diamond-shaped formations, with the leader at the apex of the triangle which the three flights formed. Another signal and the circus broke into momentary confusion, to reform with much banking and wheeling into a straight line—again with the leader ahead. Backward and forward swept the line; changed direction and wheeled until the machines formed a perfect circle in the sky.

"Splendid!" barked the man with the jerking head.

An officer, who stood a few paces to his rear, stepped up smartly, saluted, and came rigidly to attention.

"Splendid!" said the other again. "You will tell Captain Baron von Bissing that I am pleased and that I intend bestowing upon him the Order Pour la Mérite. His arrangements for my protection at Lille and Douai and Menin were perfect."

"Majesty," said the officer, "your message shall be delivered."

The sightseer swept the heavens again. "I presume that the other machine is posted as a sentinel," he said. "That is a most excellent idea—it is flying at an enormous height. Who is the pilot?"

The officer turned and beckoned one of the group behind him. "His Majesty wishes to know who is the pilot of the sentinel machine?" he asked.

The officer addressed raised his face to the heavens with a little frown.

"The other machine, general?" he repeated. "There is no other machine."

He focused his glasses on the tiniest black spot in the skies. Long and seriously he viewed the lonely watcher, then:

"General," he said hastily, "it is advisable that his Majesty should go."

"Huh?"

"I can not distinguish the machine, but it looks suspicious."

"Whoom! Whoom!"

A field away, two great brown geysers of earth leaped up into the air and two deafening explosions set the bare branches of the trees swaying.

Down the bank scrambled the distinguished party and in a few seconds the cars were streaking homeward.

The circus was now climbing desperately, but the watcher on high had a big margin of safety.

"Whoom!"

Just to the rear of the last staff car fell the bomb, blowing a great hole in the paved road and scattering stones and débris over a wide area.

The cars fled onward, skidding at every turn of the road, and the bombs followed or preceded them, or else flung up the earth to left or right.

"That's the tenth and the last, thank God!" said the sweating aide-de-camp. "Heaven and thunder! what an almost catastrophe!"

In the amazing spaces of the air, a lean face, pinched and blue with the cold, peered over the fuselage and watched the antlike procession of pin-point dots moving slowly along the snowy road.

"That's ma last!" he said, and picking up an aerial torpedo from between his feet, he dropped it over the side.

It struck the last car, which dissolved noisily into dust and splinters, while the force of the explosion overturned the car ahead.

"A bonnie shot," said Tam o' the Scoots complacently, and banked over as he turned for home. He shot a glance at the climbing circus and judged that there was no permanent advantage to be secured from an engagement. Nevertheless he loosed a drum of ammunition at the highest machine and grinned when he saw two rips appear in the wing of his machine.

By the time he passed over the German line all the Archies in the world were blazing at him, but Tam was at an almost record height—the height where men go dizzy and sick and suffer from internal bleeding. Over the German front-line trenches he dipped steeply down, but such had been his altitude that he was still ten thousand feet high when he leveled out above his aerodrome.

He descended in wide circles, his machine canted all the time at an angle of forty-five degrees and lighted gently on the even surface of the field a quarter of an hour after he had crossed the line.

He descended to the ground stiff and numb, and Bertram walked across from his own machine to make inquiries.

"Parky, Tam?"

"It's no' so parky, Mr. Bertram, sir-r," replied Tam cautiously.

"Rot, Tam!" said that youthful officer. "Why, your nose is blue!"

"Aweel," admitted Tam. "But that's no' cold, that's—will ye look at ma altitude record?"

The young man climbed into the fuselage, looked and gasped.

"Dear lad!" he said, "have you been to heaven?"

"Verra near, sir-r," said Tam gravely; "another ten gallons o' essence an' A'd 'a' made it. A've been that high that A' could see the sun risin' to-morrow!"

He started to walk off to his quarters but stopped and turned back. "Don't go near MacBissing's caircus," he warned; "he's feelin' sore."

Tam made a verbal report to Blackie, and Blackie got on to Headquarters by 'phone.

"Tam seems to have had an adventure, sir," he said, when he had induced H. Q. exchange to connect him with his general and gave the lurid details.

"It might be Hindenburg," said the general thoughtfully. "He's on the Western Front somewhere—that may explain the appearance of the circuses—or it may have been a corps general showing off the circus to a few trippers from Berlin—they are always running Reichstag members and pressmen round this front. Get Tam to make a report—his own report, not one you have edited." Blackie heard him chuckle. "I showed the last one to the army commander and he was tickled to death—hurry it along, I'm dying to see it."

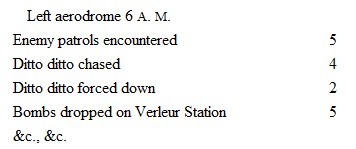

If there is one task which an airman dislikes more than any other, it is report-writing. Tam was no exception, and his written accounts of the day's work were models of briefness.

In the days of his extreme youth he had been engaged in labor which did not call for the clerical qualities, and roughly his written "reports" were modeled on the "time sheets" he was wont to render in that far-off period, when he dwelt in lodgings at Govan, and worked at McArdle's Shipbuilding Yard.

Thus:

Fortunately Tam possessed a romantic and a poetical soul, and there were rare occasions when he would offer a lyrical account of his adventures containing more color and detail. As, for example, his account of his fight with Lieutenant Prince Zwartz-Hamelyn:

"Oh, wad some power the giftie gi'e usTae see oursel's as ithers see us."Thus spake a high an' princely HunAs he fired at Tam wi' his Maxim gun.Thinkin', na doot, that bonnie ladWas lookin', if no' feelin', bad.But Tam he stalled his wee machineAn' straffit young Zwartz-Hamelyn.It was Blackie who harnessed Tam's genius for description to the pencil of a stenographer, and thereafter, when a long report was needed by Headquarters, there would appear at Tam's quarters one Corporal Alexander Brown, Blackie's secretary, and an amiable cockney who wrote mystic characters in a notebook with great rapidity.

"Is it ye, Alec?" said Tam, suspending his ablutions to open the door of his "bunk." "Come away in, man. Is it a report ye want? Sit down on the bed an' help yeersel' to the seegairs. Ye'll find the whisky in the decanter."

Corporal Brown sat on the bed because he knew it was there. He dived into his pocket and produced a notebook, a pencil and a cigaret, because he knew they had existence, too. He did not attempt to search for the cigars and the whisky because he had been fooled before, and had on two separate occasions searched the bunk for these delicacies under the unsmiling eyes of Tam and aided by Tam's advice, only to find in the end that Tam was as anxious to discover such treasures as the baffled corporal himself.

"We will noo proceed with the thrillin' serial," said Tam, spreading his towel on the window-ledge and rolling down his shirt-sleeves. "Are ye ready, Alec?"

"'Arf a mo', Sergeant—have you got a match?"

"Man, ye're a cadger of the most appallin' descreeption," said Tam severely. "A'm lookin' for'ard to the day when it'll be a coort-martial offense to ask yeer superior officer for matches—here's one. Don't strike it till ye give me one of yeer common cigarets."

The corporal produced a packet.

"A'll ask ye as a favor not to let the men know A've descended to this low an' vulgar habit," said Tam. "A'll take two or three as curiosities—A'd like to show the officers the kind o' poison the lower classes smoke—"

"Here! Leave me a couple!" said the alarmed non-commissioned officer as Tam's skilful fingers half emptied the box.

"Be silent!" said Tam, "ye're interruptin' ma train o' thochts—what did A' say last?"

"You said nothing yet," replied the corporal, rescuing his depleted store.

"Here it begins," said Tam, and started:

"At ten o'clock in the forenoon o' a clear but wintry day, a solitary airman micht hae been seen wingin' his lane way ameedst the solitude o' the achin' skies."

"'Achin' skies'?" queried the stenographer dubiously.

"It's poetry," said Tam. "A' got it oot o' a bit by Roodyard Kiplin', the Burns o' England, an' don't interrupt.

"He seemed ower young for sich an adventure—"

"How old are you, Sergeant, if I may ask the question?" demanded the amanuensis.

"Ye may not ask, but A'll tell you—A'm seventy-four come Michaelmas, an' A've never looked into the bricht ees o' a lassie since A' lost me wee Jean, who flit wi' a colonel o' dragoons, in the year the battle of Balaklava was fought—will ye shut yeer face whilst A'm dictatin'?"

"Sorry," murmured the corporal and poised his pencil.

"Suddenly, as the wee hero was guidin' his 'bus through the maze o' cloods, a strange sicht met his ees. It was the caircus of MacBissing! They were evolutin' by numbers, performin' their Great Feat of Balancin' an' Barebacked Ridin', Aerial Trapeze an' Tight-rope Walkin', Loopin' the Loop by the death-defyin' Brothers Fritz, together with many laughable an' amusin' interludes by Whimsical Walker, the Laird o' Laughter, the whole concludin' with a Graund Patriotic Procession entitled Deutschland ower All—or Nearly All."

"I ain't seen a circus for years," said the corporal with a sigh. "Lord! I used to love them girls in short skirts—"

"Restrain yeer amorous thochts, Alec," warned Tam, "an' fix yeer mind on leeterature. To proceed:

"'Can it be,' says our hero, 'can it be that Mr. MacBissing is doin' his stunts at ten-thairty o' the clock in the cauld morn, for sheer love o' his seenister profession? No,' says A'—says our young hero—'no,' says he, 'he has a distinguished audience as like as not.'

"Speerin' ower the side an' fixin' his expensive glasses on the groon, he espied sax motor-cars—"

The door was flung open and Blackie came in hurriedly. "Tam—get up," he said briefly. "All the damn circuses are out on a strafe—and we're It—von Bissing, von Rheinhoff, and von Wentzl. They're coming straight here and I think they're out for blood."

The history of that great aerial combat has been graphically told by the special correspondents. Von Bissing's formation—dead out of luck that day—was broken up by Archie fire and forced back, von Wentzl was engaged by the Fifty-ninth Squadron (providentially up in strength for a strafe of their own) and turned back, but the von Rheinhoff group reached its objective before the machines were more than five thousand feet from the ground and there was some wild bombing.

Von Rheinhoff might have unloaded his bombs and got away, but he showed deplorable judgment. To insure an absolutely successful outcome to the attack he ordered his machines to descend. Before he could recover altitude the swift little scouts were up and into the formation. The air crackled with the sound of Lewis-gun fire, machines reeled and staggered like drunken men, Tam's fighting Morane dipped and dived, climbed and swerved in a wild bacchanalian dance. Airplanes, British and German alike, fell flaming to the earth before the second in command of the enemy squadron signaled, "Retire."

A mile away a battery of A-A guns waited, its commander's eyes glued to a telescope.

"They're breaking off—stand by! Range 4300 yards—deflection—There they go! Commence firing."

A dozen batteries were waiting the signal. The air was filled with the shriek of speeding shells, the skies were mottled with patches of smoke, white and brown, where the charges burst.

Von Rheinhoff's battered squadron rode raggedly to safety.

"Got him—whoop!" yelled a thousand voices, as from one machine there came a scatter of pieces as a high-explosive shell burst under the wing, and the soaring bird collapsed and came trembling, slowly, head-over-heels to the ground.

Von Rheinhoff, that redoubtable man, was half conscious when they pulled him out of the burnt and bloody wreck.

He looked round sleepily at the group about him and asked in the voice of a very tired man:

"Which—of—you—fellows—bombed—our Kaiser?"

Tam leant forward, his face blazing with excitement.

"Say that again, sir-r," he said.

Von Rheinhoff looked at him through half-opened eyes. "Tam—eh?" he whispered. "You—nearly put an empire—in mourning."

Tam drew a long breath, then turned away. "Nearly!" he said bitterly. "Did A' no' tell ye, Captain Blackie, sir-r, that ma luck was oot?"

CHAPTER VIII

A QUESTION OF RANK

Tam stood in the doorway of Squadron Headquarters and saluted.

"Come in, Sergeant Mactavish," said Blackie, and Tam's heart went down into his boots.

To be called by his surname was a happening which had only one significance. There was trouble of sorts, and Tam hated trouble.

"There are some facts which General Headquarters have asked me to verify—your age is twenty-seven?"

"Yes, sir-r."

"You hold the military medal, the French Médaille Militaire, the Russian medal of St. George and the French Croix de Guerre?"

"Oh, aye, Captain Blackie, sir-r, but A've no' worn 'em yet."

"You were created King's Corporal for an act of valor on January 17, 1915?" Blackie went on, consulting a paper.

"Yes, sir-r."

Blackie nodded. "That's all, Sergeant," he said, and as Tam saluted and turned, "oh, by-the-way, Sergeant—we had a brass ha—I mean a staff officer here the other day and he reported rather unfavorably upon a practise of yours—er—ours. It was a question of discipline—you know it is not usual for a non-commissioned officer to be on such friendly terms with—er—officers. And I think he saw you in the anteroom of the mess. So I told him something which was not at the time exactly true."

Tam nodded gravely.

For the first time since he had been a soldier he had a horrid feeling of chagrin, of disappointment, of something that rebuffed and hurt.

"A' see, sir-r," he said, "'tis no' ma wish to put mesel' forward, an' if A've been a wee bit free wi' the young laddies there was no disrespect in it. A' know ma place an' A'm no' ashamed o' it. There's a shipyard on the Clyde that's got ma name on its books as a fitter—that's ma job an' A'm proud o' it. If ye're thinkin', Captain Blackie, sir-r, that ma heid got big—"

"No, no, Tam," said Blackie hastily, "I'm just telling you—so that you'll understand things when they happen."

Tam saluted and walked away.

He passed Brandspeth and Walker-Giddons and responded to their flippant greetings with as stiff a salute as he was capable of offering. They stared after him in amazement.

"What's the matter with Tam?" they demanded simultaneously, one of the other.

Tam reached his room, closed and locked the door and sat down to unravel a confused situation.

He had grown up with the squadron and had insensibly drifted into a relationship which had no counterpart in any other branch of the service. He was "Tam," unique and indefinable. He had few intimates of his own rank, and little association with his juniors. The mechanics treated him as being in a class apart and respected him since the day when, to the prejudice of good order and military discipline, he had followed a homesick boy who had deserted, found him and hammered him until nostalgia would have been a welcome relief. All deserters are shot, and the youth having at first decided that death was preferable to a repetition of the thrashing he had received, changed his mind and was tearfully grateful.

Sitting on his bed, his head between his hands, pondering this remarkable change which had come to the attitude of his officers and friends, Tam was sensible (to his astonishment) of the extraordinary development his mentality had undergone. He had come to the army resentfully, a rabid socialist with a keen contempt for "the upper classes" which he had never concealed. The upper classes were people who wore high white collars, turned up the ends of their trousers and affected a monocle. They spoke a kind of drawling English and said, "By gad, dear old top—what perfectly beastly weathah!"

They did no work and lived on the sweat of labor. They patronized the workman or ignored his existence, and only came to Scotland to shoot and fish—whereon they assumed (with gillies and keepers of all kinds) the national dress which Scotsmen never wear.

That was the old conception, and Tam almost gasped as he realized how far he had traveled from his ancient faith. For all these boys he knew were of that class—most of them had an exaggerated accent and said, "By gad!"—but somehow he understood them and could see, beneath the externals, the fine and lovable qualities that were theirs. He had been taken into this strange and pleasant community and had felt—he did not exactly know what he had felt. All he did know was that a brass-hatted angel with red tabs on its collar stood at the gate of a little paradise of comradeship, and forbade further knowledge of its pleasant places.

He pursed his lips and got to his feet, sick with a sense of his loss. He was of the people, apart. He was a Clydeside worker and they were the quality. He told himself this and knew that he lied—he and they stood on grounds of equality; they were men doing men's work and risking their lives one for the other.

Tam whistled a dreary little tune, took down his cap and walked over to the workshops. There was a motorcycle which Brandspeth told him he could use, and after a moment's hesitation, Tam wheeled the machine to the yard. Then he remembered that he was in his working tunic, and since it was his intention to utilize this day's leave in visiting a town at the rear of the lines, he decided to return to his bunk and change into his "best."

He opened his box—but his best tunic was missing.

"Weel, weel!" said Tam, puzzled, and summoned his batman with a shrill whistle.

"To tell you the truth, Sergeant," said the man, "Mr. Walker-Giddons and the other young officers came over for it three days ago. They got me to give it to 'em and made me promise I wouldn't say anything about it."

Tam smiled quietly.

"All right, Angus," he nodded and went back to his cycle. He did not know the joke, but it was one which would probably come to an untimely end, in view of the disciplinary measures which headquarters were taking. This incident meant another little pang, but the freshness of the morning and the exhilaration of the ride—for motorcycling has thrills which aviation does not know—helped banish all thoughts of an unpleasant morning.

He reached his destination, made a few purchases, drank an agreeable cup of coffee and discovered that he had exhausted all the joys which the town held. He had intended amusing himself through the day and returning at night, but, even before the restaurants began to fill for lunch he was bored and irritable, and strapping his purchases to the back of the cycle he mounted the machine and began his homeward journey.

It was in the little village St. Anton (in reality a suburb of the town) that he met Adventure—Adventure so novel, so bewildering, that he felt that he had been singled out by fate for such an experience as had never before fallen to mortal man.

He met a girl. He met her violently, for she was speeding along a road behind the wheel of a small motor ambulance and it happened that the road in question ran at right angles to that which Tam was following.

Both saw the danger a few seconds before the collision occurred; both applied fierce brakes, but, nevertheless, Tam found himself on his hands and knees at the feet of the lady-driver, having taken a purler almost into her lap, despite the printed warning attached to this portion of the ambulance:

Driver and Orderlies Only"Oh, I do hope you aren't hurt," said the girl anxiously.

Tam picked himself up, dusted his hands and his knees and surveyed her severely.

She was rather small of stature and very pretty. A shrapnel helmet was set at a rakish angle over her golden-brown hair, and she wore the uniform of a Red Cross driver.

"It was my fault," she went on. "This is only a secondary road and yours is the main—I should have slowed but I guess I was thinking of things. I often do that."

She was obviously American and Tam's slow smile was free of malice.

"It's fine to think of things," he said, "especially when y're drivin' an ambulance—but it's a hairse ye ought to be drivin', Mistress, if ye want to gie yeer thochts a good airin'."

"I'm really sorry," said the girl penitently. "I'm afraid your cycle is smashed."

"Don't let it worry ye," said Tam calmly. "It's no' ma bike anyway; it belongs to one of the hatefu' governin' classes, an' A've nothin' to do but mak' guid the damage."

"Oh," said the girl blankly, then she suddenly went red.

"Of course," she began awkwardly, "as I was responsible—I can well afford—"

She halted lamely and Tam's eyes twinkled. "Maybe ye're the niece of Andrew Carnegie an' ye've had yeer monthly library allowance," he said gravely, "an' maybe ye could spare a few thousand dollars or cents—A've no' got the exact coinage in ma mind—to help a wee feller buy a new whizzer-wheel. A' take it kindly, but guid money makes bad frien's."

"I didn't intend offering you money," she said hurriedly, flushing deeper than ever, "let me pull the car up to the side of the road."

Tam examined his own battered machine in the meantime. The front wheel had buckled, but this was easily remedied, and by the time the girl had brought her car to rest in a field he had repaired all the important damage.

"I was going to stop somewhere about here for lunch," she said, producing a basket from under the seat; "in fact, I was thinking of lunch when—when—"

"A' nose-dived on to ye," said Tam, preparing to depart. "Weel, A'll be gettin' along. There's nothing A' can do for ye?"

"You can stay and lunch with me."

"A've haid ma dinner," said Tam hastily.

"What did you have?" she demanded.

"Roast beef an' rice pudding," said Tam glibly.

"I don't believe you—anyway I guess it won't hurt you to watch me eat."

Tam noticed that she took it for granted that he was lying, for she served him with a portion of her simple meal, and he accepted the situation without protest.