полная версия

полная версияHeath's Modern Language Series: Mariucha

20. Sor Simona, drama en tres actos y cuatro cuadros. Madrid, Teatro Infanta Isabel, Dec. 1, 1915. Received with applause, but soon withdrawn.

The action takes place during the last Carlist war (1875) in Aragonese villages. Sister Simona is a runaway nun, thought slightly demented, who devotes herself to nursing the wounded of the war. She attempts to save the life of a young Alfonsist spy by declaring him her own son. This serves only to destroy her reputation for saintliness, and the situation is suddenly saved by an offer to exchange prisoners.

It will be seen that there is, properly speaking, no plot, and the ending is full of improbabilities. Once more Galdós, with characteristic persistence, has used the justifiable lie, which failed so signally in Los condenados. The work is saved by its poetic atmosphere and by the spiritual central figure. Charity is not to be imprisoned in convents; it is as free as the divine breath that moves the planets. God is reached by good works; the only fatherland worth fighting for is humanity; the only king, mankind. These are the teachings of Sor Simona. Her name is to be connected with Simon Peter, the cornerstone of the Church of Christ.

21. El tacaño Salomón, comedia en dos actos. Madrid, Teatro Lara, Feb. 2, 1916. (Sub-title, Sperate miseri.)

The scene is the modest home of a Madrid engraver who earns good wages, but is victimized by all who appeal to him for help. Stingy Salomón is sent him by a wealthy brother in Buenos Aires to assist his want if he will reform and acquire thrift. The engraver proves incorrigible, but, through his brother's death, receives the money nevertheless.

The play is of the same type as Celia en los infiernos, but is less interesting and even more improbable. In a way it is a complement to Pedro Minio, which taught the beauties of an open and generous life, while El tacaño Salomón appears to preach thrift. But the author has hard work to become enthusiastic over that virtue, and at the close quite lets it slip away from him. Both Celia and the present play are the work of a man who has despaired of accomplishing any good in society by logical and practical means, and resorts to the illusions of a child dreaming of a fairy godmother.

22. Santa Juana de Castilla, tragicomedia en tres actos. Madrid, Teatro de la Princesa, May 8, 1918.

A picture of the old age and death of Juana la Loca, the daughter of the Catholic Kings, and widow of Philip the Handsome. The Queen's mad passion for Philip is barely mentioned, her figure is idealized, and she is made a symbol of humility, self-effacement, and love for the humble. Closely guarded by a harsh agent of her son Charles V, she escapes for a day to a country village, where she talks in a friendly way with the peasants, discussing their problems with a simplicity which conceals much wisdom. To those who wish to use her name as a standard to restore the power of the common people, she insists that she desires nothing but darkness and silence in which to end her days. She had been suspected of heresy, because she read Erasmus, but the Jesuit Francisco de Borja, a man of saintly life, is with her at her death, and bears witness that her faith is untainted and that she will receive in the bosom of God the reward for her many sufferings.

As far back as 1907 Galdós was deeply interested in the life of this wretched Queen: "No hay drama más intenso que el lento agonizar de aquella infeliz viuda, cuya psicología es un profundo y tentador enigma. ¿Quién lo descifrará?"14 In his interpretation of her last moments, Galdós has made the figure of the Queen vaguely symbolic of present-day Spain, like Laura of Alma y vida. But she embodies still more the soul of the aged author, blind, feeble, living in silence and obscurity, absorbed in contemplation of approaching death.

The construction of the play is flawless, of diaphanous simplicity, the dialog is pure and brief, the characters are delicately outlined in a few sure touches. "A mournful, somber triptych," says Luis Brun of its three acts, "the central panel of which is lit by a ray of light." An atmosphere of serene melancholy broods over this admirable drama, fitting close to the career of a well-poised spirit.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

No definitive critical study has yet been made of any side of Galdós' work. The following list, by no means complete, does not include general histories of Spanish literature, encyclopedia articles or reviews in contemporary periodicals of first performances. The best of the last-named are those by Gómez de Baquero in España moderna. Criticisms dealing only with the novels of Galdós are not cited here.

1. BIOGRAPHYLeopoldo Alas (Clarín), "Galdós" in Obras completas, tomo I, Madrid, 1912.

L. Antón del Olmet and A. García Carraffa, Galdós, Madrid, 1912. [Contains the most information.]

"El Bachiller Corchuelo" (González Fiol), "Benito Pérez Galdós," in Por esos mundos, vol. 20 (1910, I), 791-807; and vol. 21 (1910, II), 27-56. [Important.]

William Henry Bishop, in Warner's Library of the World's Best Literature, vol. XI, pp. 6153-63.

"El Caballero Audaz" (José María Carretero), Lo que sé por mí, 1ª serie, Madrid, 1915, pp. 1-11.

E. Díez-Canedo, "La Vida del Maestro," in El Sol, Jan. 4, 1920.

Archer M. Huntington, "Pérez Galdós in the Spanish Academy," in The Bookman, V (1897), pp. 220-22.

Rafael de Mesa, Don Benito Pérez Galdós, Madrid, 1920.

Emilia Pardo Bazán, "El Estudio de Galdós en Madrid," in Nuevo teatro crítico, agosto de 1891, pp. 65-74. (Obras completas, vol. 44.)

B. Pérez Galdós, "Memorias de un desmemoriado," in La esfera, vol. III, 1916 (especially the first two instalments).

B. Pérez Galdós, Prólogo to J. M. Salaverría, Vieja España, Madrid, 1907.

Camille Pitollet, "Comment vit le patriarche des lettres espagnoles," in Revue de l'enseignement des langues vivantes, Feb. 1918 (vol. XXXV).

Camille Pitollet, "Le monument Pérez Galdós à Madrid," in Revue de l'enseignement des langues vivantes, Feb. 1919 (vol. XXXVI).

Luis Ruiz Contreras, Memorias de un desmemoriado, Madrid, 1916, pp. 10, 65-72.

2. CRITICISMJ. M. Aicardo, De literatura contemporánea, Madrid, 1905, pp. 316-50. [A Catholic point of view.]

Leopoldo Alas (Clarín), Galdós, Madrid, 1912. [Already a classic.]

Leopoldo Alas (Clarín), Palique, Madrid, 1893.

Rafael Altamira, De historia y arte (estudios críticos), Madrid, 1898, pp. 275-314.

Rafael Altamira, Psicología y literatura, Madrid, 1905, pp. 155-56 and 192-98.

Andrenio (Gómez de Baquero), Novelas y novelistas, Madrid, 1918, pp. 11-112.

Anonymous, "Benito Pérez Galdós," in The Drama, May, 1911, pp. 1-11 (vol. I).

Azorín, "Don Benito Pérez Galdós," in Blanco y negro, no. 1260 (July 11, 1915).

Azorín, Lecturas españolas, Madrid, 1912, pp. 171-76.

R. E. Bassett, in Modern Language Notes, XIX (1904), pp. 15-17.

Luis Bello, Ensayos e imaginaciones sobre Madrid, Madrid, 1919, pp. 95-129.

Christian Brinton, "Galdós in English," in The Critic, vol. 45 (1904), pp. 449-50.

Manuel Bueno, Teatro español contemporáneo, Madrid, 1909, pp. 77-107.

Barrett H. Clark, The Continental Drama of To-day, New York, 1915, pp. 228-32.

Barrett H. Clark, in Preface to Masterpieces of Modern Spanish Drama, New York, 1917.

José Díaz, Electra, Barcelona, 1901.

Havelock Ellis, "Electra and the progressive movement in Spain," in The Critic, vol. 39 (1901), pp. 213-217.

Havelock Ellis, "The Spirit of Present-day Spain," in The Atlantic Monthly, vol. 98 (1906), pp. 757-65.

A. Gassier, Théâtre espagnol, Paris, 1898, pp. 308-13.

J. Geddes, Jr., Introduction to edition of Marianela, New York, 1903.

Georges Lenormand, "A propos de l'Electra de D. Benito Pérez Galdós," in Revue hispanique, VIII (1901), pp. 567-73.

J. León Pagano, Al través de la España literaria, Barcelona, 1904, II, 77-112.

Eduardo de Lustonó, "El primer drama de Galdós," in Nuestro tiempo, 1902, I, pp. 155-65.

E. Martinenche, "El Abuelo," in Revue latine, IV, 419-28.

E. Martinenche, "Le théâtre de M. Pérez Galdós," in Revue des deux mondes, 5me période, vol. 32, pp. 815-50 (1906). [This is, as far as it goes, by far the best study yet made of Galdós' drama. It appeared in a Spanish translation in España moderna, no. 210, pp. 118-58.]

Antonio Maura, Necrología de D. Benito Pérez Galdós, discurso pronunciado en la Real Academia Española. Madrid, 1920. [Contains as appendix a useful Catálogo sincrónico of Galdós' works, compiled by Cotarelo.]

M. Menéndez y Pelayo, "Discurso leído ante la Real Academia Española en la recepción pública del 7 de febrero de 1897" (reprinted in his Estudios de crítica literaria, 5ª serie).

Luis Morote, Teatro y novela, Madrid, 1906, pp. 59-75, 259-70.

E. Pardo Bazán, "Realidad," in Obras completas, vol. VI, 197-239. [A splendid interpretation written in 1892.]

R. D. Perés, "Casandra," in Cultura española, 1906, pp. 135-38.

Ramón Pérez de Ayala, Las máscaras, Madrid, 1917, pp. 17-102. [By a fervent admirer.]

J. Pérez de Guzmán, "Electra en América," in La Ilustración española y americana, 1901, II, pp. 230-31.

Ricardo Rojas, El Alma española, Valencia, n.d., pp. 87-106.

Boris de Tannenberg, "B. Pérez Galdós," in Bulletin hispanique, II (1900), pp. 340-50.

C. A. Turrell, Introduction to Contemporary Spanish Dramatists, Boston, 1919, pp. 10-12.

F. Vézinet, Les maîtres du roman espagnol contemporain, Paris, 1907, pp. 41-128.

R. W. Waldeck, "Benito Pérez Galdós, Novelist, Dramatist and Reformer," in The Critic, vol. 45 (1904), pp. 447-49.

Elizabeth Wallace, "The Spanish Drama of To-day," in The Atlantic Monthly, vol. 102 (1908), pp. 357-66.

José Yxart, El arte escénico en España, I, Barcelona, 1894, 309 to end, passim. [Objective and historical.]

MARIUCHA

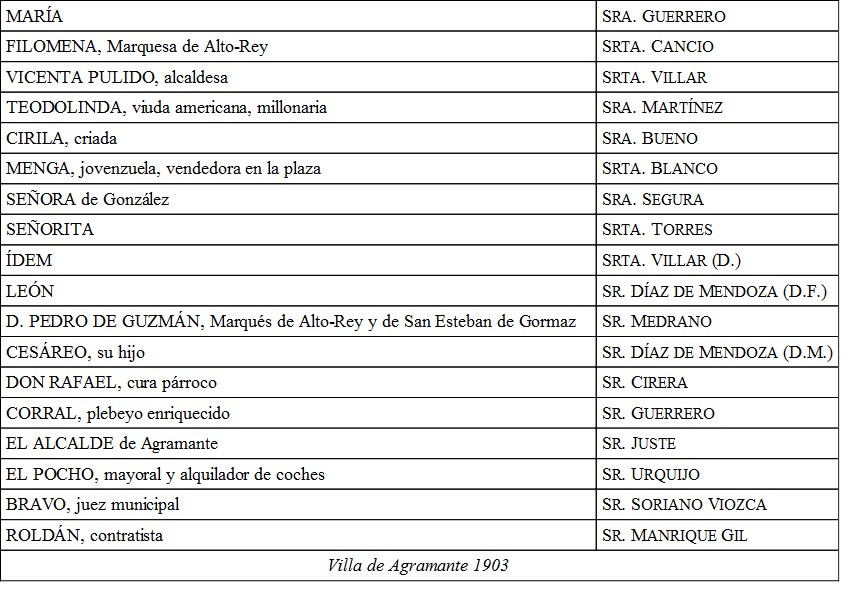

PERSONAJES

MARIUCHA

ACTO PRIMERO

Sala en el palacio de Alto-Rey. El soberbio artesonado es el único vestigio de la antigua magnificencia. Las paredes desnudas; el mueblaje moderno, poco elegante; algunas piezas, ordinarias. Puerta al fondo y a la derecha. A la izquierda, ventana o balcón. Cerca de éste una mesa de escribir. A la derecha, sillón de respeto, sillas. Es de día.

Escena Primera

Cirila, arreglando y limpiando los muebles; Corral, El Pocho, que entran por el fondo. Corral viste con afectación y mal gusto, ostentando brillantes gordos en la pechera, cadena de reloj muy llamativa y sortijas con piedras de valor.

Pocho. ¿Dan su permiso?

Cirila. Adelante.

Corral. ¿No han vuelto de misa los señores?

Cirila. No tardarán. (Displicente.) ¡Vaya, otra vez aquí estos moscones!

Pocho. Otra vez, y cien más, hasta que…

Corral. Perdone la señora Cirila, yo no vengo a cobrar.

Cirila. Viene a fisgonear, que es peor, y a meter sus narices en las interioridades de la casa…10

Corral. Ea, no despotrique, señora.

Cirila. (Aparte.) ¡Farsante!

Pocho. Yo no hago papeles. Vengo por el aquél de mi propio derecho. (Saca un papel y lo muestra.) El Sr. D. Pedro de Guzmán, Marqués de Alto-Rey y de San Esteban de Gormaz, es en deber a Francisco Muela, apodado El Pocho, la cantidad de…

Cirila. Basta.

Pocho. Por cuatro servicios de coche…

Cirila. ¡Agobiar al señor por tal porquería!…

Corral. Ya cobrarás, Pocho. (Dando largas.) Ten paciencia…

Pocho. ¡Paciencia!… que es como decir hambre.

Cirila. (Incomodada, señalándoles la puerta.) Hagan el favor… Tengo que hacer…

Pocho. Yo espero al señor.

Corral. Dos preguntas no más, señora Cirila, y perdone. Aún no hace un mes que estos señores Marqueses vinieron acá de Madrid huyendo de la quema. ¿Es cierto que se encuentran ya en situación tan precaria que…?

Cirila. Para nadie es un secreto que los que ayer fueron poderosos hoy no lo son.

Corral. Sí: ya saben hasta los perros de la calle que la casa de Alto-Rey es casa concluida. Hace más de veinte años que viene cayendo, cayendo, y por fin… (Con afectada pena.) ¡Las volteretas que de este mundo loco!… En la villa se dice que los señores Marqueses han llegado a carecer hasta de lo más preciso para la manutención.

Pocho. Y que se ven y se desean para poner un puchero.

Cirila. ¡Eh… habladurías!

Corral. (Queriendo internarse por la derecha.) Déjeme, déjeme ir a la cocina a ver qué es lo que guisan…

Cirila. (Deteniéndole.) Alto ahí… ¡Qué desvergüenza!

Pocho. ¡Si ni tan siquiera tendrán lumbre!

Corral. Hay que ver…

Pocho. (Por Cirila.) ¡Cómo les tapa la miseria! Ésta no les abandona en la desgracia.

Corral. Eso es nobleza.

Cirila. Gratitud. Les quiero…

Corral. Particularmente a la señorita María.

Cirila. ¡Mi niña del alma! Yo la crié; la he servido desde que vino al mundo. Más que cariño, por ella tengo adoración.

Pocho. Y qué re-bonita, y qué re-maja, y qué re-salerosa es la niña, ¡Cristo con ella! No le faltará un ricacho que la saque de pobre. Anímese, don Faustino… Usted rico, usted el más elegante caballero de nuestra villa… ¡Qué mejor proporción…!

Corral. (Pavoneándose.) Verdaderamente, no es uno saco de paja… De menos nos hizo Dios.

Pocho. Pues si yo fuera don Faustino del Corral, cualquiera me quitaba a mí esa niña, ¡Cristo con todos! Si tuviera yo esos diamantes en la pechera, esa cadena de reloj y esos anillos refulgentes, y lo que hay en casa, ¡Cristo conmigo! los dinerales que diz que tenemos en el Banco, ¿eh?… aguardando colocación…

Corral. No es tanto, Pocho. Algo se ha trabajado y no falta para unas sopas. (A Cirila.) Ahora, la última pregunta si usted no se incomoda.

Cirila. Diga.

Corral. ¿Es cierto que el propietario de este palaciote de Alto-Rey lo cede gratuitamente a los señores Marqueses?

Cirila. Así lo entiendo.

Pocho. ¡Y luego dicen…! ¡Vaya, que estos nobles tronados siempre caen de pie! Vendió el Marqués este caserón hace diez años por un pedazo de pan…

Corral. ¿Hase visto mayor locura? Si hubiera estado yo en Agramante, no se me escapa esa ganguita… Compró la casa el sastre Diego López, que ha sacado ya triple del coste con el producto de las estancias bajas y altas que tiene alquiladas. Y ahora, el hombre puede permitirse un rasgo: cede al Marqués las habitaciones mejores…

Cirila. (Que ha mirado por el fondo.) Los señores vienen.

Corral. (Aparte al Pocho.) Ten comedimiento, Pocho. Hazte cargo de la pobreza…

Pocho. ¿Pues y la mía? ¡Cristo con…! (Corral le manda callar. Se apartan a la izquierda.)

Escena II

Los mismos; Don Pedro, cabizbajo: detiénese en la puerta como esperando a alguien. Conserva en su miseria la nobleza de la figura. El traje, aunque revelando bastante uso, es de corte y telas elegantes. Acude Cirila a recogerle el abrigo y sombrero.

Cirila. ¿Y la señora Marquesa?

Don Pedro. Detrás viene con María y el señor Cura. (Entra despacio, abstraído.) ¿Qué… hay visitas?

Corral. (Oficioso.) Señor Marqués, ¿cómo va ese valor?

Don Pedro. Tirando, amigo, tirando… (Sobresaltado,al ver al Pocho.) ¡Otra vez este maldito Pocho!

Cirila. ¡Desdichado señor!… ¡A lo que ha llegado! (Vase por la derecha.)

Pocho. Vuecencia me dijo que hoy…

Don Pedro. (Con arrebato de cólera, bastón en mano.) Dije a usted que le avisaría…

Pocho. Perdone vuecencia… pero…

Don Pedro. Es mucho molestar… ¡Es grande impertinencia…!

Pocho. Necesidad, señor. Soy un pobre.

Corral. Paciencia, Pocho. Puedes volver…

Don Pedro. Cuando se le avise… Espere… (Se sienta en el sillón.)

Pocho. (Con entereza.) Podré alimentarme de tronchos de berza, de cortezas de chopo; pero no de las buenas palabras de vuecencia. Págueme, o de aquí me voy al Juzgado municipal…

Corral. ¡Pocho…!

Don Pedro. (Variando de tono ante la amenaza.) ¡Qué injusta desconfianza!… Pocho, venga usted aquí. (Llamándole, cariñoso.) Mi buen amigo… (Le toma la mano.) ¿Cómo puede dudar…?

Pocho. No es duda, es pobreza.

Don Pedro. (Dolorido, con afectada mansedumbre.) Vaya, vaya, sosiéguese el buen Pocho. (Dándole palmaditasen la mano.) Y no dude que, con el pago, tendrá una buena gratificación… Es muy justo. (Entran por el fondo Filomena y don Rafael.)

Pocho. Yo cedo a vuecencia la propina si hoy mismo…

Don Rafael. ¡Pocho…! (Con un castañeteo de lengua como el que se usa para echar a los perros, le despide señalándole la puerta.)

Pocho. Ya, ya… (Por D. Pedro.) ¡Cristo con él, con su madre y con toda su casta! (Vase rápidamente.)

Escena III

Don Pedro, Corral, Filomena, Don Rafael. La Marquesa de Alto-Rey revela menos que el Marqués, en su traza y vestimenta, la decadencia social. Viste traje negro elegante; mantilla.

Don Pedro. (Inquieto.) ¿Y María?

Don Rafael. En la plaza quedó con las de González.

Filomena. Entretenidita, viendo esos tipos de los pueblos, los pintorescos trajes, la animación del mercado…

Corral. (Saludándola.) Señora Marquesa, tengo el honor…

Filomena. Señor de Corral, mucho gusto… (Se quita la mantilla.)

Don Pedro. (Afectuoso, cogiéndole la mano.) Querido Corral, sea usted indulgente con mi desgracia, la cual no sólo me aflige a mí, sino a los amigos que vienen a verme, pues poco grato ha de serles oír mis lamentos, y ver espectáculos como estas embestidas del Pocho…

Corral. No se hable más de eso.

Don Rafael. Y sobre todo, no se exaspere, Marqués… Tómelo con calma… Ya vendrán días mejores…

Don Pedro. Yo confío en que el Gobierno…

Filomena. Por la Virgen, no me hables de Gobiernos…

Don Pedro. En la Providencia, sí: a eso voy. Quiero decir que Dios inspirará al Gobierno para que…

Don Rafael. (Aprobando.) ¡Mucho!

Don Pedro. También espero auxilio de las personas de nuestra clase. Imposible que permanezcan indiferentes…

Filomena. Bien podrán ser nuestros iguales o el Gobierno instrumentos de que Dios se valga para salvarnos. Pero en Dios está toda mi esperanza.

Don Rafael. Sí, sí: Dios…

Don Pedro. (Muy nervioso se levanta y se pasea por la escena.) ¿Pero a qué espera?

Filomena. Paciencia, Pedro. Para mirar por nosotros, allá quedó nuestro hijo Cesáreo…

Don Pedro. (Exasperado.) ¿Pero qué hace en Madrid Cesáreo, pregunto yo, si no revuelve el mundo por sacarnos de este pantano?

Corral. (Recordando.) Tengo el gusto de anunciar a los señores Marqueses que su hijo D. Cesáreo llegará hoy.

Don Pedro. (Gozoso.) ¡Mi hijo… aquí!

Filomena. (Gozosa.) ¡Cesáreo! ¿Cómo lo sabe usted?

Corral. Por un telegrama que recibió esta mañana el Alcalde.

Don Pedro. Me sorprende mucho.

Filomena. A mí no, sabiendo que está aquí Teodolinda.

Don Pedro. La ricachona americana, la super-mujer, poseedora, según dicen, de un capital de diez millones de pesos… No creo en cuentos de hadas; no creo que existan diez millones de duros, ni que una viuda los posea.

Don Rafael. ¿Ni creerá usted que le ha dado la ventolera de adquirir las propiedades más valiosas de la provincia?

Don Pedro. (Escéptico.) Tampoco… Ni creo que con esa señora, con ese mito, tenga relación el viaje de Cesáreo.

Corral. Que en Madrid fueron novios o cosa tal, se ha dicho en Agramante.

Filomena. Es cierto: en Madrid, el invierno último.

Don Pedro. Pero aquello pasó… pura flirtation, galanteo fugaz…

Filomena. ¡Ah!… no sabemos…

Don Pedro. (Malhumorado.) Digo que terminó.

Filomena. Muy pronto lo afirmas.

Don Rafael. (Con cierto misterio.) Yo puedo asegurar que ayer, hablando con Teodolinda…

Don Pedro. (Con súbito interés.) ¿Qué…?

Filomena. (Lo mismo.) ¿Qué…?

Don Rafael. Pues hablando ayer con ese Potosí en figura humana… fue a entregarme una cantidad, y no floja, para los pobres…

Don Pedro. ¿Y qué dijo?

Don Rafael. No sé cómo ni por qué nombramos a los señores Marqueses de Alto-Rey… Se habló de…

Corral. Estaba yo presente. Se habló del desastre de esta noble familia…

Don Rafael. Hizo grandes elogios de Cesáreo, de su inteligencia, de su gallardía…

Corral. Y al fin dijo que no pensaba volver a casarse.

Don Rafael. (Con viveza y enojo.) No: no dijo eso, Corral.

Corral. Don Rafael, mire que estoy bien seguro…

Don Rafael. (Con energía.) No dijo eso, sino todo lo contrario. Y yo me permití aconsejarle… vamos, le indiqué… cuán conveniente le será un sostén… un compañero de la vida que le ayude a llevar la carga de tan desmedidas riquezas.

Don Pedro. (Excitadísimo.) Mi querido Corral, usted, que es la gaceta de Agramante, hágame el favor de enterarse del telegrama recibido por el Alcalde… si es verdad que viene Cesáreo…

Filomena. Y a qué hora…

Corral. Voy al punto.

Don Pedro. Infórmese también de si esa señora…

Corral. Ya saben que alquiló la finca de Lugones, con magnífico parque…

Don Rafael. Y esta noche da una fiesta… al aire libre.

Corral. Lo que llamamos garden party, o garden no sé qué, con baile, buffet, farolitos…

Filomena. Querido Corral, no se entretenga…

Corral. Vuelvo. (Vase presuroso.)

Escena IV

Don Pedro, Filomena, Don Rafael; después Cirila.

Filomena. ¡Qué paso lleva el oficioso señor!

Don Pedro. Muestrario de pedrería falsa…

Don Rafael. Falsa, no: todo lo que lleva al exterior es de ley. El corazón sí que es falso, y la voluntad puro vidrio.

Don Pedro. ¿Tiene dinero este hombre?

Don Rafael. Don Faustino del Corral, o de los Corrales, no se dejará ahorcar por un milloncejo de pesetas.

Filomena. ¡Jesús me valga!

Don Pedro. Hará préstamos en condiciones ventajosas.

Don Rafael. Suele dar dinero al tres por ciento mensual, con garantía hipotecaria.

Don Pedro. Y a retro quizás. El hombre no quiere arriesgarse.

Filomena. ¿Y a los pobres no da?

Don Rafael. ¡Oh! sí: en la suscripción para la Casa de Misericordia figura con una suma mensual.

Filomena. Será considerable.

Don Rafael. Noventa céntimos.

Cirila. (Entrando por el fondo con cartas y periódicos.) El correo. (Dirígese a la mesa de la izquierda, a la que va también don Pedro.)

Filomena. (A la derecha, con don Rafael.) La sordidez, ave rastrera, hace casi siempre sus nidos en las arcas más llenas de caudales.

Don Rafael. Así como la caridad, ave del Cielo, suele acomodarse en las arcas vacías. ¡Triste humanidad!

Filomena. Por eso yo, en mis angustias actuales, me acuerdo de los que aun son más pobres que yo…

Don Rafael. (Elogiando.) ¡Mucho, mucho!

Don Pedro. (A Cirila.) Aguárdate, que algo hay que llevar al correo. (En voz alta, mirando el sobre de una carta.) Filomena, carta de tu madre. (La da a Cirila,que la lleva a su señora.)