Полная версия

Flaming Sussex

‘No, no, Sefton. That was ages ago.’

‘That was about two weeks ago.’

‘Anyway. It was dreadfully dreary. They expected me to write about such terrible frivolities.’

‘Really?’

‘Yes, really.’

‘Such as?’

‘Accordion pleats or bishop’s sleeves or whatever other silly thing is in fashion.’

‘But I thought you were interested in fashion.’

‘Of course I am, Sefton, but I’m not interested in writing about it. People who write about fashion seem to me about as dull as people who write about medieval patristics.’ Thus spoke her father’s daughter. ‘People could go around in bustles and jodhpurs for all I care, Sefton – and I really don’t care.’

For someone who really didn’t care we seemed to spend much of our time packing and unpacking her clothes trunks.

‘Anyway, you know me, Sefton.’

‘I do?’

‘I have a taste for much stronger stuff, Sefton.’ Which was certainly true. ‘No. I’m now a contributing editor for Axis.’

‘Axis?’ I said. ‘Something to do with mechanics? Geometry?’

‘It’s an art magazine, silly. You must have heard of it.’

‘I can’t say I have, Miriam, no.’

‘Axis? Really?’

‘No.’

‘A Quarterly Review of Contemporary “Abstract” Painting and Sculpture?’

‘Oh,’ I said, ‘that Axis.’

From the teetering pile on the table she plucked the latest issue of the magazine, which I flicked through while she went to finish her packing.

‘That’ll be an education for you,’ she said, as she disappeared into her bedroom.

It certainly was. Most of the articles were entirely – one might almost say immaculately – unreadable, as if written from a strange place where the English language had been entirely reinvented solely to bamboozle and confuse. One contributor, for example, described some blobby sort of a painting as ‘rampageous and eczematous’; another described an artist whose work consisted entirely of everyday household objects hung on washing lines as having ‘traversed the farthest realms of the aesthetic to reinvent the very idea of objecthood’; Miriam’s article was perhaps marginally less preposterous than the rest, though equally vexatious. She described some artist’s series of abstract sketches as a work of ‘profound autofiction’: to me the work looked like a series of a child’s drawings of black and white squares and triangles balancing on colourful balls.

Miriam’s restless pursuit of knowledge of all kinds was of course quite admirable, her hunger for new experiences rivalling only her father’s great lust for learning. Having endured a privileged, if rather peculiar upbringing and education at some of the country’s best schools, and courtesy of one of the country’s best minds, Miriam often expressed to me her wish that she had gone to Cambridge or to Oxford to study PPE (which, to my shame, I usually referred to as GGG, or ‘Ghastly Girls’ Greats’, an easy alternative to Classics). ‘All these women who go to Lady Margaret Hall do make one feel terribly inadequate, Sefton.’ During our work together on The County Guides, Miriam slowly but surely reinvented herself, becoming more and more an autodidact in the manner of her father: she went to fewer tennis parties with girls called Diana and Camilla, took up the saxophone and the uilleann pipes, added Arabic and Mandarin Chinese to her many languages, and ranged widely in her reading, from Freud in German to Céline in French. She was naturally formidable: over time she became utterly extraordinary. It was sometimes difficult to see how anyone could possibly keep up with her.

When I occasionally asked why she had taken up with this unsuitable man or other, she would simply say, ‘Because everyone else is so boring, Sefton.’ Boredom was her bête noire. It could get her into terrible trouble. Her most recent boyfriend was a man so daring and adventurous that he had joined Britannia Youth, the neo-fascist group that specialised in sending impressionable young British schoolboys to Nazi rallies in Germany.

‘Roderick was just such fun!’ she said.

Roderick had lasted about two weeks.

‘Right,’ she said, barrelling out of her bedroom carrying a large handbag.

‘Crocodile?’ I nodded towards the bag.

‘Alligator, actually, Sefton. Can’t you tell? Are you ready?’

‘I am. Is that all you’re taking?’ I was confused. Miriam did not travel light. Part of the challenge of travelling with Miriam and Morley was travelling with Miriam’s clothes: for even the shortest journey she would pack Chinese robes, leopard-skin hats and kid leather gloves.

‘Yes.’

‘That’s it?’

‘The rest is already in the Lagonda, Sefton. László gave me a hand last night. Do you know László?’

‘I don’t think I do, no.’

‘You must know László.’

Miriam was always amazed when it turned out that I didn’t know anyone she knew – because of course she knew everyone who counted. I did not, however, to my knowledge, know anyone named László.

‘Bruno?’

‘No.’ As far as I was aware my life was both László- and Bruno-free.

‘Serge?’

Ditto.

‘Anyway, lovely chaps. They got the Lagonda all packed up for me. Now, what do you think?’ She gestured towards a brooch she was wearing.

‘It’s very pretty.’

‘Pretty, Sefton?’

‘Very pretty.’

‘Very pretty? For goodness sake, man, it’s a nineteenth-century Tiffany orchid brooch with diamond-edged petals.’

‘Yes, I thought so. And very pretty.’

‘It was a gift from a friend, actually.’

‘Very good.’ Miriam was forever receiving gifts from friends, always men – and always jewellery, though once there was the gift of a De Dion Bouton car, which for a moment rivalled the Lagonda in her affections. The men came and went but the gifts remained.

‘Do you know, Sefton,’ she told me on more than one occasion, ‘the perfect condition for a woman is either to be engaged, or to be widowed.’

We were about to leave the apartment, Miriam equipped with bag and key in hand.

‘Oh, I almost forgot.’ She dashed back into her bedroom and reappeared moments later carrying what looked like a small furry blanket clutched to her chest.

‘What is that?’

‘It’s a Bedlington, Sefton.’

‘A Whatlington?’

‘A Bedlington. A Bedlington Terrier.’

‘A dog?’

‘Yes, of course a dog.’

‘Oh, Miriam.’

‘What do you mean, “Oh, Miriam”?’

‘A dog, Miriam.’

‘I like dogs, Sefton.’

‘You didn’t get it at Club Row?’

‘I certainly did,’ said Miriam, offended. ‘There was a chap as I was leaving the market who was packing up for home and he had this little thing all on his own and—’

‘From Club Row? You’ll be lucky if he lasts a week,’ I said.

‘Sefton!’ She covered the dog’s ears. ‘Don’t talk like that around Pablo.’

‘Pablo?’

‘Picasso, yes.’

‘You’ve named your dog after the artist.’

‘Yes. Why shouldn’t I?’

A dog that looked less like Picasso it would be hard to imagine: he was a dog that looked like a Picasso. Everything about him was wonky, or wrong: rather than a dog, he resembled a lamb, except he was a lamb with a bluish, velvety sort of coat, a high arched back, a narrow but bulbous head, a tail that tapered to a point, and ears that hung down to what looked like two little white pom-poms. He had a mild, bewildered expression on his face and was without a doubt one of the most peculiar-looking creatures I’d ever seen. Miriam obviously adored him.

‘Take these,’ she said, thrusting a brown paper bag into my hands. ‘The chap threw in a bag of arrowroot biscuits.’

‘Marvellous,’ I said.

‘Now. Pablo has left a little present in the bedroom.’

‘Oh no.’ So this was the source of the smell.

‘And I just wondered if you’d be a darling and tidy it up, while I run down to the car? There’re some old newspapers in there that should do the job.’

‘Miriam!’

‘Thank you, darling! See you in a min!’

Pablo’s gift duly disposed of, I made my way down to the Lagonda, which was parked at the back of the building.

Miriam had donned her leather driving gloves.

‘Are we not waiting for your father?’ I asked.

‘Oh no, no, no,’ said Miriam. ‘Sorry, I should have said. We’re meeting him down in Brighton.’

‘Right.’

‘Come on, Sefton. In you pop. No time to lose!’

With Miriam driving, I was left in the passenger seat with the Bedlington, who instantly – quite understandably – became unsettled as Miriam started up the engine and gunned down towards Camden Town. I held on tight to the poor pooch and did my best to calm him: in return, he relieved himself over my trousers.

Damp and headachy, heading out of London, I listened as Miriam recapped for me some of the things her father wanted us to see in Sussex, including Arundel Castle – ‘The archetypal English castle, Sefton, according to Father. Norman and Early English, Gothic and Gothic Revival, Victorian and Modern, absolutely unmatched’ – and many other high points, including Beddingham, Seaford, Alfriston and Litlington, all places I’d never heard of and had absolutely no desire to visit.

‘Do you know Elgar?’ asked Miriam, somewhere around Crawley.

I admitted that I did know Elgar, forgetting, as so often, that for Miriam knowing someone of renown meant actually knowing them, rather than knowing of them.

‘Marvellous, isn’t he? Father and I have spent many happy hours with Elgar at Brinkwells in Fittleworth. He has marvellous views to Chanctonbury Ring. When did you visit?’

I had not visited. I had no desire to visit.

It had been a long day.

And I had no idea when we eventually reached Brighton that it was going to be an even longer night.

The Bedlington

A Late Night Sort of Town

CHAPTER 9

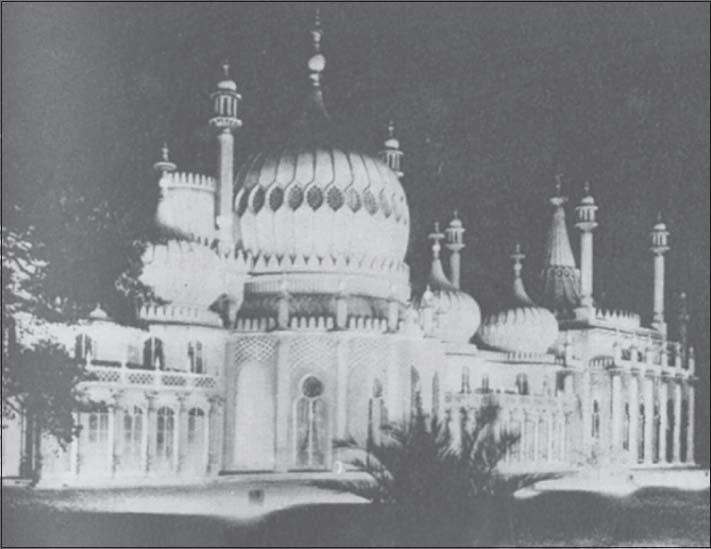

DUE TO CIRCUMSTANCES partly within my control (poor map-reading) and partly without (slow-moving vehicles; cattle being driven along the road on the way to an abattoir; a family apparently moving house using a large cart, upon which they had balanced a dog in a kennel, some rabbits in a hutch, a canary in a cage, a goldfish in a bowl, some hens in a chicken house, a garden shed, bags of logs and several sacks of coal), we arrived rather late in Brighton. Fortunately for us, Brighton was and is, and with any luck will always be, the kind of town that stays up to welcome late-arriving visitors. Cruising into town on a chilly autumn evening around 10 p.m. – by which time most, if not all English towns and villages have long since shut up shop, pulled the curtains tight and retired safely to bed till morning – on the streets of Brighton there were still dog-walkers, cyclists, courting couples and children out playing. According to Morley in The County Guides: Sussex, ‘Eastbourne stands aloof, Hastings is of the people, but Brighton alone has a continental character.’ The place certainly had a character continental that evening, as if it were an English town holidaying late in the season somewhere in the south of France. And as it turned out, the evening became more and more continental as it wore on.

Molly Harper, Morley’s American adventuress, was giving a recital at the Theatre Royal, or, rather, had been giving a recital at the Theatre Royal. The performance was almost over by the time we arrived, which was a cause for great celebration on Miriam’s part.

‘Thank goodness for that, Sefton,’ she said. ‘I have absolutely no desire to hear the American Oval sing. It’s bad enough having to hear her talk. Come on, let’s find a quick drink, and then we shall go and rescue Father from her carmine clutches.’

We parked conveniently outside the theatre and persuaded – or, rather, Miriam persuaded – an usher to serve us in the bar, where we happily sat alone drinking gin cocktails until the audience departed, whereupon we made our way backstage and soon found Molly’s dressing room by following the tinkling sound of laughter.

‘Enter!’ came the cry, as Miriam knocked briskly on the door.

The first thing I noticed on entering was the large presentation basket of fruit – Fortnum’s, naturally – and numerous exquisite bouquets of flowers, which were most certainly not in season and therefore most certainly wildly expensive. Set among this extraordinary colourful display, like a life-size mascot Pierrot, was Molly Harper herself.

It has to be said that Miriam’s description of Molly was not entirely inaccurate: she did indeed have eyes that looked like they might winkle you out; she did indeed have rather ludicrous eyebrows, suggesting a look of constant surprise verging on astonishment; and she did, in that American fashion, appear in every way to be a slightly inflated version of herself. She had a ready laugh, for example, that to English ears rang rather hollow, and she was seemingly equipped with endlessly bubbling reserves of the kind of enthusiasm that is entirely alien to the slow and long-cooled Brit. Her entire manner and appearance – her eyebrows, her hair, her enthusiasm, her vivid painted nails – struck one as being rather more suitable for the stage than for any average everyday activities. Larger than life, she was also rather larger than her tight, billowing black and white evening gown naturally allowed. With her white arm-length buttoned gloves, her perpetual look of astonishment, and her raven-black soignée hair, she had all the appearance of a rather sinister, pampered silken panda.

What Miriam had not mentioned in her description, however, was that Molly looked very much like an older, fuller version of … Miriam.

Swanton Morley of course looked precisely as he always did: he was someone whose success had been achieved entirely by dint of his own efforts and by unchanging daily habits and rituals, which meant that there was little about him that ever seemed to alter. Photographs of him aged thirty resembled exactly photographs of him aged forty and fifty – not so much Dorian Gray as an immovable and immutable Easter Island statue. He always wore exactly the same clothes, or at least exactly the same sort of clothes, a uniform that he had chosen as a young man and which he had stuck with ever since, the Morley Style: the sober-coloured suits in finest tweed or worsted, the tightly buttoned waistcoat with its additional notebook and pencil pockets, the sharply cuffed trousers, the tailoring always stiff, conservative and redolent of an earlier age. His tailor was a man in Norwich, a Mr Barton Bendish, who kept premises in an arcade near the city’s market and whom Morley had known since childhood. Mr Bendish was, according to Morley, the equal of any tailor on Savile Row and a man capable of transforming even the stoutest and dowdiest John Bull into a super-sleek Sydney Greenstreet. He often suggested to me that he could provide me with an introduction to Mr Bendish, who would happily provide me with outfits similar to Morley’s own, an offer I always refused since at the time I cultivated a studiedly carefree appearance that was quite in contrast to Morley’s rather more sober-suited image. Though how I wish now that I had a Barton Bendish of my own. The only sartorial eccentricity Morley ever allowed himself were his brown brogue boots, always highly polished, and his bow ties, many of them patterned to resemble fine Scottish knitwear. This evening, at the Theatre Royal, he looked as well-tended as ever, in a three-piece light grey suit, with a red and white polka-dot bow tie – not merely smart, I thought, but actually elegant, as if the mere presence of a woman like Molly were slowly turning his tweed to silk.

Unchanging in appearance he may have been, but Morley was of course entirely unpredictable in conversation – and this evening was no exception.

‘Billy Button buttoned his bright brown boots,’ he was saying as we entered. ‘Good evening, Miriam. Good evening, Sefton.’

Molly beckoned us into the dressing room.

‘Billy Button buttoned his bright brown boots,’ she repeated, after Morley. ‘Your father is teaching me some English tongue-twisters, Miriam.’

‘Is he now?’ said Miriam.

‘Betty Blue was beating butter,’ said Morley.

‘Betty Blue was beating butter,’ repeated Molly.

‘Miriam?’ said Morley, nodding towards her. ‘Betty …’

‘I am not practising tongue-twisters, thank you, Father. It’s far too late in the evening.’

‘Never too late for tongue-twisting,’ said Morley.

‘Gig-whip, gig-whip, gig-whip, gig-whip,’ said Molly.

‘Oh yes, that’s one of our favourites,’ said Morley. ‘Gig-whip, gig-whip, gig-whip, gig-whip. Sefton?’

‘Gig-whip, gig-whip, whip-wig, wig-gip …’ I gave up.

‘Not as easy as it sounds, is it?’ said Morley.

‘Indeed,’ I agreed.

‘We’ve not met, have we?’ asked Molly, breaking off from her tongue-twisting but remaining seated among the flowers and fruit and extending her hand.

‘No. I’m Stephen Sefton,’ I said, leaning forward, not entirely sure whether to kiss her hand, shake it, or kneel before her and receive a blessing.

‘Ah, yes, Swanton has told me so much about you,’ said Molly. No one called Morley Swanton.

We shook hands.

‘All of it good, I hope,’ I said.

‘Hardly any of it good,’ Molly said with a laugh. ‘And all the better for that. Can I offer you a drink?’ She indicated some unopened bottles – champagne, wine, lemonade – on the dressing room table.

I looked at Miriam out of the corner of my eye. She gave a sharp, vigorous shake of her head.

‘I won’t, thank you,’ I said. ‘It’s been a long day. Miriam and I have just motored down from London. We should probably retire.’

‘You are clearly as self-disciplined as your famously abstemious employer,’ said Molly.

‘Perhaps not quite,’ I said.

‘You must have something,’ she said. ‘Here.’ She got up, took two bottles of what looked like American lemonade, pushed down the marbles in the two bottle tops simultaneously, one in each hand, and thrust them towards us. ‘A little trick I learned back home.’

‘Flexibility of the lips is very important, you see,’ said Morley, who was still on the subject of tongue-twisters.

‘Oh yes, flexibility of the lips is very important, isn’t it, Miriam?’ said Molly.

‘I have no idea,’ said Miriam, rather huffily.

‘Vowels as well as consonants suffer terribly from a lack of good lip movement,’ said Morley. ‘The lips are part of the resonating system, you see, which is what makes each human voice unique.’ His own voice was as rapid as ever and as strange, rattling like a kettle on the range. ‘The lungs and the diaphragm are the bellows, the larynx the vibrator, and this’ – he tapped a finger to his head – ‘the resonator. Molly has a magnificent resonator, Miriam.’

‘I’m sure she has, Father,’ said Miriam, as Morley and Molly started to make a humming sound together.

Miriam huffed.

Even by the high standards of embarrassment I had become accustomed to while working with Morley and Miriam, it was all rather embarrassing. Morley was clearly as fascinated with Molly as she was intent on fascinating him. They had first met, I later discovered, at a meeting of Morley’s so-called Bonhomie Club, a group of friends whom he brought together once a month in London, for the purposes of discussion, playing chess, and listening to music. Molly had been invited by Morley to give a recital, and the two of them had quickly become inseparable.

‘Your father, Miriam!’ said Molly, breaking her gaze and her hum with Morley. ‘He’s incredible. I mean, his life, his experiences. His capacity for hard work! I’m surprised it doesn’t simply sap all the energy out of him!’

‘Oh, I’m sure you’ll find other ways of sapping the energy out of him.’

‘His knowledge!’

‘A little knowledge is a dangerous thing,’ said Miriam.

‘“A little learning is a dangerous thing,”’ corrected Morley.

‘“Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring: There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,”’ said Miriam.

‘“And drinking largely sobers us again,”’ said Morley, completing the quotation. ‘Sefton?’ he asked.

‘Dryden?’ I suggested.

‘Pope!’ said Morley. ‘Essay on Criticism.’

‘Marvellous!’ said Molly, clapping her gloved hands together. ‘You know, you’re all just so … curious.’

‘That’s one word for it,’ said Miriam.

‘I’m terribly curious myself,’ said Molly.

‘Really?’

‘Oh yes. I married my first husband entirely out of curiosity.’

‘Isn’t one supposed to marry for love?’ said Miriam.

‘One is supposed to do a lot of things, my dear,’ said Molly. ‘Do you know the final trio from Der Rosenkavalier?’

‘Not off the top of my head,’ said Miriam. ‘No.’

‘“Hab mir’s gelobt”,’ said Morley.

‘Indeed,’ said Molly. ‘In which the Marschallin gives up her young lover, Octavian, when she realises that he is in love with Sophie.’

Molly closed her eyes for a moment and then quietly began to sketch out the melody with her – admittedly – extraordinary voice, a soft, clear, luminous soprano. Morley closed his eyes and hummed along.

I thought for a moment that Miriam might actually be physically sick, but fortunately we had the Bedlington with us, who made his presence known at this point by attempting to climb up onto Molly’s lap, interrupting the impromptu recital.

‘Well, well, who is this little fellow?’ Molly said, scooping him up.

‘This is Pablo,’ I said.

‘Pablito, surely,’ said Molly, petting him like a baby.

Miriam snorted derisively.

‘I met Picasso at a dance in Madrid some years ago. Did I ever tell you, Swanton?’

‘I don’t think so, my dear,’ said Morley.

‘Yes. I’d been performing – Teatro de la Zarzuela – and there had been a dinner in my honour and we all went dancing in this wonderful little taverna, and Picasso was there and he really was quite a … bull of a man.’

‘The minotaur of modern art,’ said Morley.

‘Exactly!’ said Molly. ‘The minotaur of modern art! How clever!’

Miriam sighed so loudly it sounded like a rushing wind had entered the room: her exasperation, I could tell, was reaching the point of no return and great regret. Thank goodness, there came a knock at the door.

‘Enter!’ cried Molly, though almost before she had uttered the word the door had already opened and a rather ugly bald-headed man with bulgy eyes poked his head around.

‘This is Giacomo,’ said Molly. ‘He’s my manager.’