Полная версия

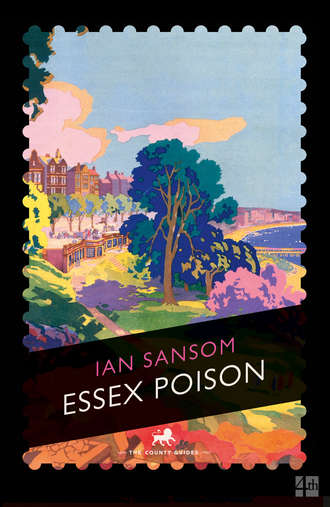

Essex Poison

As we made our way down Becontree Avenue I was struck first of all not by the buildings but by the extraordinary sight of what seemed like never-ending rows of privet hedges leading off in every direction, all short and trimmed at regulation waist height and which made it look as though the actual buildings of Becontree were some kind of a weird garden planted in behind the hedges, almost as an afterthought, square, overgrown red brick flowers and shrubs. The Becontree hedges, perhaps more than anything else, sum up that dream of another England that Morley so admired and cherished, a perfect, planted petit-bourgeois green and pleasant land.

‘Ghastly,’ said Miriam.

A brightened, whitened East End

It was certainly strange – like a brightened, whitened East End, as though having been boil-washed and run through the mangle. There were tramways and cheap cars and uniform shopfronts all with identical awnings. There were long monotonous rows of houses, each with a handkerchief patch of garden out front, all equivalent in size and shape, except for those few homes set further back from the road around miniature greens, and odd corner sites that had young trees planted, and fresh, ugly churches. It all looked terribly clean and also rather Dutch; something to do with the pitch of the roofs, perhaps, and also the fact that everywhere one looked there were men and women on bicycles, furiously pedalling, as if the life of the nation itself depended on the men and women of Essex getting to work on time. And yet somehow, for all it looked longingly towards Europe for its architectural inspiration, it also seemed inevitably and undeniably American: the wide streets clearly built not for boulevardiers and bicycles but for cars and trucks and lorries, and the low-rise buildings not the stuff of the Low Countries but rather of the New World, the only ornament and interest the advertising hoardings that glued the streets together with Parkinson’s Biscuits, Eno’s Fruit Salts, Lavvo and Pumphrey’s Lemon Curd. We pulled over beneath a sign for Bile Beans, in a spot designated by another sign for ‘PARKING’, in front of a shop called Clifford’s, at the corner of Becontree Avenue and Valence Avenue. A convoy of lorries piled high with sand and gravel came thundering past, spraying fine dust and diesel fumes in their wake.

‘What on earth is this place?’ asked Miriam.

‘This,’ I said, ‘is the modern world. I’ll maybe get a few photographs,’ I said, ‘and then we can be on our way.’

‘Well, if this is the modern world, Sefton,’ said Miriam, ‘I want no part of it.’ Which of course is what made Miriam so thoroughly modern.

As I was carefully framing a shot for Morley, featuring the dusty boulevards of Becontree, and while Miriam sat smiling regally at the passers-by ogling both her and the Lagonda – not an everyday sight in south Essex, either of them – a man came sauntering proprietorially along the pavement towards us. His hat was pulled down tight on his head, his hands deep in the pockets of his double-breasted overcoat, and he had the kind of bullying walk that suggested he was prepared to pick a fight with anyone, at any time, and preferably now. It was Willy Mann, Mr Klein’s business agent and fixer. The last time I’d seen him was just the night before, when he was all shiny and naked in the Turkish baths: now, thank goodness, he was cooled off and dressed, though no less menacing.

‘Well, well,’ said Willy. He was the very definition of shifty, with a habit of moving and shrugging inside his clothes, as though avoiding a punch, or calculating his next blow. ‘Sefton, again.’ He nodded towards my cuts and bruises. ‘Trouble?’

‘Hello, Willy,’ I said. ‘Sorry, I didn’t recognise you with your clothes on.’

‘A joke, presumably?’

‘Don’t encourage him,’ said Miriam, lighting a cigarette.

‘Hello, hello,’ said Willy, removing his hat and going to shake Miriam’s hand. ‘You’re not with him, surely, a fine young lady like yourself?’

Fortunately Miriam was accustomed to compliments from men far more accomplished than Willy and was more than ready with a put-down.

‘“With him” in the strict sense of being accompanied by him, sir, yes.’ She paused and took a long thoughtful drag on her cigarette, effectively establishing her dominance over the conversation, over the cigarette, and of course over Willy. ‘But certainly not “with him” in the broader sense of having, possessing and thus, crudely and colloquially speaking, being in a relationship “with him”, if that’s what you’re asking, certainly not, no.’ She took another long draw on her cigarette and raised an eyebrow at Willy. ‘So it rather depends in what sense you were using the term, doesn’t it?’

‘Goodness me. Lively one,’ said Willy to me. ‘Not her who roughed you up, was it?’

‘I haven’t laid a finger on him,’ said Miriam.

‘More’s the pity, eh?’ said Willy, nudging me.

Miriam gave a furious little growl at this and flashed her ruby-red fingernails at Willy, cigarette aloft, one of her more alarming gestures, suggesting a panther – or some blonde equivalent thereof – about to pounce. ‘I suppose you’d better introduce me to your witty little friend here, Sefton,’ she said wearily to me. ‘Since you are “with” me, though only in the strict and obvious sense.’

‘Yes, of course,’ I said. ‘This is Willy Mann, Miriam. Willy, this is Miriam Morley.’

‘Very pleased to make your acquaintance,’ said Willy, with, I thought, rather too much feeling in his ‘very’: Miriam tended to have an instant mesmerising effect on men. I recall there being one or two chaps in fact who proposed marriage within an hour of meeting her. I hoped Willy wasn’t going to embarrass himself.

‘And where do you boys know each other from?’ asked Miriam.

‘Sefton and I—’

‘Have a lot of mutual friends,’ I interrupted.

‘I didn’t know you had any friends,’ said Miriam, blowing smoke, as she liked to, as though in an aside.

‘Sefton always likes to play his cards close to his chest,’ said Willy. ‘I didn’t have you down as a man to be driving a Lagonda, for example.’

‘I think you’ll note that I’m driving the Lagonda, actually,’ said Miriam, from the driver’s seat. ‘Sefton is my passenger.’

‘Indeed,’ said Willy. ‘All the more remarkable, Sefton.’

‘Anyway,’ I said, ‘what are you doing up around these parts, Willy?’

‘I might have asked you the same thing, old chap. Not your usual stomping ground, is it?’

‘Not exactly,’ said Miriam, on my behalf. ‘But here we are. And why are you here, Willy?’

‘Mr Klein has business interests up here,’ said Willy.

‘Ah, yes,’ I said, vaguely remembering what Willy had explained to me the night before.

‘And who is this Mr Klein when he’s at home?’ asked Miriam.

‘He’s a businessman,’ said Willy. ‘Good friend of ours.’

‘And what would be Mr Klein’s business in Becontree, of all places, if you don’t mind my asking?’ Miriam was cursed with her father’s curiosity.

‘Do you have half an hour?’ asked Willy.

‘No,’ I said.

‘It rather depends,’ said Miriam.

‘I thought perhaps I might show you something,’ said Willy.

‘Did you now?’ said Miriam. ‘And I wonder what that might be?’

She had a habit sometimes, I noticed, when she was talking to men, of moving her cigarette between her fingers very slightly and very carefully. She was doing it now – a subtle and expressive gesture.

‘You’ll have to trust me to find out,’ said Willy.

‘Hmm. What do you think, Sefton? Should we trust Willy here to show us something? Or should we not?’ And she again moved the cigarette ever so slightly between her fingers. She had us both in the palm of her hand.

CHAPTER 7

THIS IS ENGLAND

AS SO OFTEN, with so many people, and so many things, what Willy actually had to show us was something of an anticlimax. What he had to show us was a building site on Klein’s new development on the edge of Becontree. He was shouting facts and figures at us, vainly trying to impress Miriam, as lorries went thundering past.

‘You see, apart from the construction,’ he yelled, ‘there’s all the haulage and the materials themselves. So in the average house you’ve got perhaps forty thousand bricks, plus your lime and sand and cement, and then there’s your plaster and roofing tiles, fireplaces and what have you. Which is about a hundred and fifty tonnes worth per house, which has all got to be hauled to site somehow – plus your excavations. So you’re looking at quite a job.’

‘And quite a profit,’ said Miriam.

‘Exactly,’ said Willy.

‘So Mr Klein builds the houses, he provides the materials, and he provides the means by which the materials are transported? Is that right?’ said Miriam.

‘That’s right.’

‘Quite a business model.’

‘I didn’t know he was into haulage as well,’ I said.

‘Indeed he is, Sefton,’ said Willy, as a lorry nudged its way slowly through the building site towards us.

‘Quite the all-rounder, your Mr Klein,’ said Miriam.

‘You could say that. He was rather hoping in fact that Sefton here might be able to assist us with one or two of our current projects.’

‘Sefton!?’ Miriam laughed.

‘Yes.’

‘Assisting your Mr Klein?’

‘Yes.’

‘Has he met him?’

‘Thank you for that vote of encouragement, Miriam,’ I said.

‘Well anyway, he’s too late, isn’t he, your chap,’ said Miriam. ‘Sefton’s already in steady employment – working for me.’

‘And I’m sure you work him pretty hard,’ said Willy.

‘You have no idea,’ said Miriam.

I wondered how much Mr Klein might be paying.

The lorry was now reversing its way perilously close to the Lagonda.

‘There we are,’ said Willy. ‘That’s what I like to see. Another lorryload down from the quarries.’ And as if on cue, the lorry upended its vast load of sand, close enough to the Lagonda to coat it in a fine pale yellow mist.

‘Little bit close for comfort,’ said Willy. ‘Sorry about that.’

‘Lovely lorry,’ said Miriam, taking no notice of Willy: she never really cared about the things that other people cared about. I thought for a moment she’d said ‘lovely lolly’.

‘A Thornycroft Trusty,’ she continued. ‘The lorry.’

‘How on earth do you …’ began Willy. ‘This is quite a girl you have here, Sefton.’

Miriam was quite a girl, but she certainly wouldn’t thank Willy for telling her so.

‘Father’s a great admirer of Thornycrofts,’ she said. ‘He has a little Handy that he runs on the estate.’

‘Really?’ I said.

‘Who’s your father?’ asked Willy. ‘Not that it’s any of my business.’

‘Swanton Morley,’ said Miriam. ‘Not that it’s any of your business.’

‘The People’s Professor?’

‘The very man.’

‘Good stock then,’ said Willy, as if appraising a prize cow. ‘I am impressed by your choice, Sefton.’

‘Might I refer you to my earlier answer about being “with” Sefton only in the strict sense of being accompanied by him, sir. He has no more “chosen” me than he has chosen the weather. I am an entirely separate entity.’

‘An entirely separate and unpredictable entity,’ I added.

‘Thank you, Sefton,’ said Miriam. ‘I’ll take that as a compliment.’

‘Anyway,’ said Willy, interrupting Miriam’s teasing, ‘this is the finished article.’ He pointed to a large plain, pebble-dashed building to our left. It looked rather … municipal.

‘It’s certainly spacious,’ said Miriam.

‘It’s maisonettes, actually,’ said Willy.

‘Oh,’ said Miriam. ‘I thought you meant the whole building.’

‘No, no! That’s a dozen flats there, miss,’ said Willy.

‘How continental,’ said Miriam.

‘They’re very well appointed inside,’ said Willy.

‘I’m sure they are.’

‘Perhaps we’ll make a house call, shall we?’ said Willy. ‘See it for ourselves? Come on.’

‘We should really be getting on, Willy,’ I said.

‘Nonsense,’ said Miriam. ‘Bit of colour for the book, eh, Sefton? Some photographs? Also, some material for my new column.’

‘You’re not a journalist, are you?’ asked Willy, suddenly alarmed.

‘No, no, silly!’ said Miriam. ‘I just write about my life for a woman’s magazine.’

‘Talents that know no end,’ said Willy, who was clearly smitten, as so many before and after were smitten.

We picked our way amid piles of sand and gravel and pallets containing bricks and long white wooden A-frames and beams and trusses and Willy rapped officiously on the door of one of the ground-floor maisonettes in the pebble-dashed building. A climbing rose had been rather forlornly planted by the door, nailed and tied with string to some sort of frame made from scavenged wood.

A woman answered almost immediately, wearing a pinny and a sharp expression. Willy explained that he was a representative of the firm that was building the maisonettes and wanted to show some visitors round.

‘Good!’ said the woman.

‘Excellent,’ said Willy.

‘I’ve been waiting for you.’

‘So,’ continued Willy, walking straight past her into the narrow hallway, indicating for us to follow. There was just room for the four of us to stand shoulder to shoulder.

‘I’ve written to you three times,’ said the woman. ‘And I’ve spoken to your foreman goodness knows how many. Where have you been?’

‘As you can see,’ said Willy, opening a narrow door to a tiny bathroom to the right. ‘All the houses come with indoor sanitary facilities.’

‘Well, well,’ said Miriam. ‘How marvellous.’

‘It doesn’t flush,’ said the woman. ‘It’s not worked for months. We’re having to slop it out.’

‘Oh dear,’ said Miriam.

‘Have you brought your tools?’ continued the woman. ‘Are you going to fix it now?’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Willy. ‘I represent the builders rather than the landlords, madam, I’m afraid,’ said Willy. ‘I thought I explained.’

‘We need this fixed,’ said the woman.

‘And I’m sure it will be fixed,’ said Willy. ‘If you don’t mind?’ He leaned past the woman and tapped a wall. ‘Solid brick construction throughout, as you can hear.’ The wall gave a hollow echo in response. ‘Homes for heroes!’

‘It’s all partition,’ said the woman. ‘No insulation. Walls are like paper. Look, the other problem is this damp in the bedroom. There’s mushrooms growing in here!’ She started to walk into the room leading directly off the hall, but Willy turned right instead and we followed into what was the one and only reception room, just big enough for a tiny square table on a rag rug on the lino floor, and an old iron fold-up bed concertinaed under the window. ‘And a fireplace in every room,’ continued Willy, gesturing towards the tiny brown-tiled hearth.

‘Gives no heat,’ said the woman. ‘We all have to sleep in here together in the winter, for the warmth.’

‘You’ve got electric lights, I see,’ said Miriam, gesturing at the bare bulb dangling over the table.

‘Doesn’t work half the time.’

‘Kitchen,’ said Willy, gesturing towards a room leading off the reception room, which accommodated a Baby Belling, a sink, a few shelves, and nothing else.

‘Kitchenette,’ said the woman.

‘A few chromium fittings and it’d be the equal of anything on Park Lane!’ said Willy.

‘What’s he talking about?’ said the woman.

‘And so concludes our tour,’ said Willy, beating a hasty retreat to the front door.

The woman grabbed at Miriam’s arm as we caught up with Willy in the hall. ‘You’re not thinking of renting one of these, are you?’ she asked her.

‘No,’ said Miriam.

‘Good. Because my advice is don’t. These places are worse than the tenements.’

‘Surely not,’ said Miriam.

‘Teething troubles,’ said Willy. ‘Only to be expected. Rome wasn’t built in a day, eh?’

‘We’ve been here a year,’ said the woman.

‘Well, thank you, madam, for showing us round,’ said Willy.

‘Yes,’ said Miriam. ‘It’s really been an education.’

‘Bit of a whistlestop, I’m afraid,’ said Willy, striding away from the building as fast as he could, and lighting a cigarette. ‘But gives you an idea, I hope.’ He stood at a distance and admired the building. ‘What do you think?’

‘Absolutely ghastly,’ said Miriam. She was never shy of stating her opinions.

‘Can I offer you a cigarette?’ Willy asked Miriam.

‘I have my own, thank you.’ Which she did not.

‘It’s not for the likes of you, of course,’ said Willy, his eyes fixed on Miriam. I’d seen it before: men often became drawn into argument with Miriam, mistaking the argument for a kind of flirtation. I often made the same mistake myself.

‘Not for the likes of anyone, I wouldn’t have thought,’ said Miriam.

‘People need houses,’ said Willy.

‘People need homes more than they need houses,’ said Miriam, ‘and I’m afraid I find it difficult to see how your buildings could ever be regarded as homes.’

‘Matter of taste, perhaps?’ said Willy.

‘Nothing to do with taste,’ said Miriam. ‘And everything to do with quality – and intention.’

Willy took another couple of quick, excited drags on his cigarette and then ground it out underfoot. ‘With all due respect, miss, I hardly think you’re an expert in housing.’

‘With all due respect, sir, I hardly think you and your Mr Klein are experts either, on the evidence of these buildings.’

Willy laughed.

‘Hardly a laughing matter, is it?’ said Miriam. ‘Jerry-building? I’m sure there must be rules and regulations about this sort of thing, aren’t there?’

‘There are indeed, miss. And we know exactly what we’re doing, thank you.’

‘Yes,’ said Miriam. ‘I’m sure you know exactly what you’re doing. That’s hardly reassuring though, is it? Have you by chance visited the Karl-Marx-Hof municipal buildings in Vienna?’

‘I can’t say I have,’ said Willy.

‘Well, I have. Father and I visited, for some article he was writing. And I have to say, I thought they were a fine example of how to provide housing for the masses.’

‘I don’t know how they do things in Vienna, miss. But this is England.’

‘And might we English not expect housing of a similar standard to the Austrian?’ said Miriam.

‘Anyway,’ said Willy, realising that he wasn’t going to get anywhere with Miriam, but playing a final gambit. ‘Perhaps I can take you for dinner sometime and we could discuss it further?’

‘I don’t think so,’ said Miriam. ‘I doubt we’d have anything to talk about beyond your blatant buccaneering, sir. We should really get on, shouldn’t we, Sefton?’

‘Yes,’ I agreed.

Willy looked crushed – and determined. I’d seen the look before. There was not a man who didn’t think he was a match for Miriam, and who wasn’t.

‘Well, just remember Mr Klein’s offer, Sefton,’ he said to me. ‘Give it some thought, won’t you?’

‘I certainly will, Willy,’ I said.

‘He certainly won’t, Willy,’ said Miriam.

I was glad to get out of Becontree.

CHAPTER 8

THE DAGENHAM GIRL PIPERS

I CAN ONLY DESCRIBE THE SCENE that we eventually came upon in Colchester as ‘strange’. (Morley, I should say, did not like the word ‘strange’. He regarded it as lacking in specificity, ‘a terrible failing in a word’ – see Morley’s Vocabulary Builder: Words to Use and Words to Avoid (1932) – as if it were somehow its own fault.)

Morley’s ambitious itinerary for our trip up through Essex suggested that after Becontree we were supposed to visit Epping Forest (‘Poor John Clare!’ read his scribbled notes. ‘Mad as a hatter!’), Romford’s famous brewery, Tiptree for the jam, the villages around Saffron Walden (‘Cromwell’s headquarters – the heart of Radical Essex!’), the Marconi works in Chelmsford (‘Inventive Essex!’), before finally heading to Colchester for the Oyster Feast. But after our tour with Willy Mann of the jerry-built houses of Becontree we were forced to cut short our peregrinations and to press on directly to Colchester to make it in time for the Oyster Feast. Miriam, needless to say, drove like a maniac. I shan’t even attempt to describe the Essex countryside: it all looked perfectly pleasantly blurred.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.