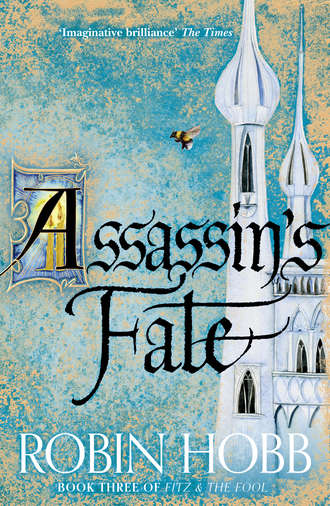

Assassin’s Fate

Полная версия

Assassin’s Fate

Жанр: приключенияфэнтезизарубежные приключениязарубежное фэнтезикниги о приключенияхгероическое фэнтези

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2019

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу