Полная версия

The Duchess

The Duchess

GEORGIANA:

DUCHESS OF DEVONSHIRE

AMANDA FOREMAN

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Introduction

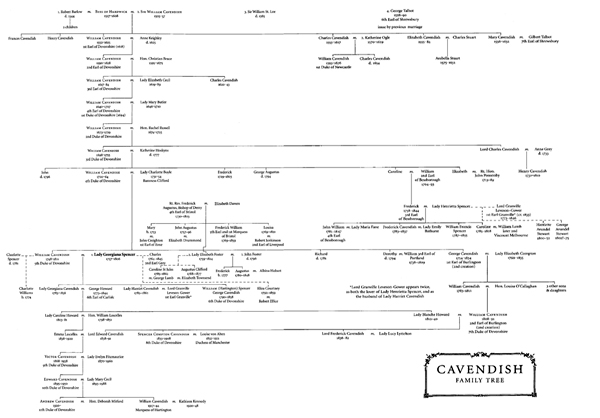

Family Trees

Part One: Débutante

1 Debutante: 1757–1774

2 Fashion’s Favourite: 1774–1776

3 The Vortex of Dissipation: 1776–1778

4 A Popular Patriot: 1778–1781

5 Introduction to Politics: 1780–1782

Part Two: Politics

6 The Cuckoo Bird: 1782–1783

7 An Unstable Coalition: 1783

8 A Birth and a Death: 1783–1784

9 The Westminster Election: 1784

10 Opposition: 1784–1786

11 Queen Bess: 1787

12 Ménage à Trois: 1788

13 The Regency Crisis: 1788–1789

Part Three: Exile

14 The Approaching Storm: 1789–1790

15 Exposure: 1790–1791

16 Exile: 1791–1793

17 Return: 1794–1796

18 Interlude: 1796

19 Isolation: 1796–1799

Part Four: Georgiana Redux

20 Georgiana Redux: 1800–1801

21 Peace: 1801–1802

22 Power Struggles: 1802–1803

23 The Doyenne of the Whig Party: 1803–1804

24 ‘The Ministry of All the Talents’: 1804–1806

Epilogue

Select Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Notes

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

Biographers are notorious for falling in love with their subjects. It is the literary equivalent of the ‘Stockholm Syndrome’, the phenomenon which leads hostages to feel sympathetic towards their captors. The biographer is, in a sense, a willing hostage, held captive for so long that he becomes hopelessly enthralled.

There are obvious, intellectual motives which drive a writer to spend years, and sometimes decades, researching the life of a person long vanished, but they often mask a less clear although equally powerful compulsion. Most biographers identify with their subjects. It can be unconscious and no more substantial than a shadow flitting across the page. At other times identification plays so central a role that the work becomes part autobiography as, famously, in Richard Holmes’s Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer (1995).

In either case, once he commits himself to the task, the writer embarks on a journey that has no obvious route for a destination that is only partly known. He immerses himself in his subject’s life. The recorded impressions of contemporaries are read and re-read; letters, diaries, hastily scribbled notes, even discarded fragments are scrutinized for clues; and yet the truth remains maddeningly elusive. The subject’s own self-deception, mistaken recollections, and the hidden motives of witnesses conspire to make a complete picture impossible to assemble. Finally, it is intuition and a sympathy with the past which supply the last missing pieces. It is no wonder that biographers often confess to dreaming about their subjects. I remember the first time Georgiana appeared to me: I dreamt I switched on the radio and heard her reciting one of her poems. That was the closest she ever came to me; in later dreams she was always a vanishing figure, present but beyond my reach.

Such profound bonds have obvious dangers, not least in the disruption they can inflict upon a biographer’s life. Sometimes the work suffers; its integrity becomes jeopardised when, without realising it, a biographer mistakes his own feelings for the subject’s, ascribing characteristics that did not exist and motives that were never there. In his life of Charles James Fox, the Victorian historian George Trevelyan insisted that Fox held to a strict code of morality regarding the sexual conquest of aristocratic women; he only seduced courtesans. Trevelyan, perhaps, had such a code, but Fox did not. There is ample evidence to suggest that the Whig politician had several affairs with married women of quality, including Mrs Crewe and possibly Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. Her first biographer, Iris Palmer, was similarly wishful in her description of Georgiana as a ‘simple woman’ without ambition except in her desire to help others. Palmer also claimed, in the face of contrary evidence, that Georgiana was only unfaithful to her husband with one man, Charles Grey. Both biographers illustrate how easy it is to fall prey to the temptation to suppress or ignore unwelcome evidence.

Fortunately, the emotional distance required to construct a narrative from an incoherent collection of facts and suppositions provides a powerful counterbalance. By deciding which pieces of the puzzle are the most significant – not always an easy task – and thereby asserting their own interpretation, the biographer achieves a measure of separation. The demands of writing, of style, pace and clarity, also force a writer to be more objective. Numerous decisions have to be made about conflicting evidence, or where to place the correct emphasis between certain events. Having previously dominated the biographer’s waking and sleeping life, the subject gradually diminishes until he or she is contained on the page.

I discovered Georgiana in 1993, while researching a doctoral dissertation on English attitudes to race and colour in the late eighteenth century. I was reading a biography of Charles Grey, later Earl Grey, by E. A. Smith, and came across one of her letters. I was already familiar with Georgiana’s career as a political hostess and as the duchess who once campaigned for Charles James Fox, but I had never read any of her writing, and knew little of her character. I was struck by her voice, it was so strong, so clear, honest and open, that she made everything I subsequently read seem dull by comparison. I lost interest in my doctorate, and after six months I had read just one book on eighteenth-century racial attitudes. Whenever I did go to the library it was to look for biographies of Georgiana.

There have been three previous biographies about her, all of them remarkably similar. Iris Palmer’s The Face without a Frown, written in 1944, was a novelization of Georgiana’s early life. It made no claim to be a historical biography, although Palmer did quote from Georgiana’s letters. The other two, The Two Duchesses, by Arthur Calder-Marshall (1978), and Georgiana, by Brian Masters (1981), also concentrated on her early life. Both Calder-Marshall and Masters were probably influenced by the edited selection of Georgiana’s letters, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, published by the Earl of Bessborough in 1955. (It was only much later that I discovered the extent of Lord Bessborough’s editing for myself.) None of the books, not even the Bessborough edition of her letters, portrayed the Georgiana whose voice I felt I had heard. Eventually I realized I would never be satisfied until I had followed the trail to its source. Oxford accepted my explanation and graciously allowed me to start again and begin a new D.Phil, on Georgiana’s life and times. A short while later I decided to write her biography in addition to the doctorate.

As Georgiana’s letters are scattered around the country, I planned to be on the road for eighteen months and set off in the summer of 1994, having finally passed my driving test on the seventh attempt. My fears about starting a new project were subsumed by the act of driving on the motorway for the first time. I began my search at Chatsworth in Derbyshire, Georgiana’s home during her married life. Its archives, hidden away inside a subterranean labyrinth of corridors, contain over 1,000 of her letters. They revealed so much of her daily life that it seemed as though I were watching a play from the corner of the stage. The impression of being an invisible, perhaps even an uninvited, spectator remained with me throughout my research.

The ‘Stockholm Syndrome’ came upon me suddenly, and I was caught even before I noticed it happening. One day in the Public Record Office at Kew, while reading a vicious letter from one of Georgiana’s rivals, I found myself becoming furious on her behalf. This was the beginning of my obsession with Georgiana, fuelled by frustration at the empty spaces in the Chatsworth archives where someone had either destroyed her letters or censored them with black ink. It only began to wane after I had filled in the missing days and months in Georgiana’s life from other sources: the archives at Castle Howard, private collections, the British Library, and libraries and record offices all over Britain.

By the time I had consigned Georgiana to the page a different picture of her had emerged. Previous accounts portrayed her as a charismatic but flighty woman; I see her as courageous and vulnerable. Georgiana indeed suffered from the instability which often accompanies intelligent and sensitive characters. She was thrust into public life at the age of sixteen, unprepared for the pressures that quickly followed and unsupported in a cold and loveless marriage. Though most of her contemporaries adored her because she seemed so natural and vibrant, only a few knew how tormented she was by self-doubt and loneliness. Georgiana was not content to lead the fashionable set nor merely to host soirées for the Whig party, instead she became an adept political campaigner and negotiator, respected by the Whigs and feared by her adversaries. She was the first woman to conduct a modern electoral campaign, going out into the streets to persuade ordinary people to vote for the Whigs. She took advantage of the country’s rapidly expanding newspaper trade to increase the popularity of the Whig party and succeeded in turning herself into a national celebrity. Georgiana was a patron of the arts, a novelist and writer, an amateur scientist and a musician. It was her tragedy that these successes were overshadowed by private and public misfortune. Ambitious for herself and her party, Georgiana was continually frustrated by restrictions imposed on eighteenth-century women. She was also a woman who needed to be loved, but the two people whom she loved most – Charles Grey and the Duke of Devonshire’s mistress Lady Elizabeth Foster – proved incapable of reciprocating her feelings in full measure. Georgiana’s unhappiness expressed itself destructively in her addiction to gambling, her early eating disorders, and her deliberate courting of risk. Her battle to overcome her problems was an achievement equal to the triumphs she enjoyed in her public life.

Georgiana’s relationships with men and women cannot be categorized by twentieth-century divisions between what is strictly heterosexual and homosexual. Nor did she think about the rights of women or entertain the same notions of equality that characterize modern feminism. It would be foolish to separate Georgiana from her era and call her a woman before her time; she was distinctly of her time. Yet her successful entry into the male-dominated world of politics, her relationship with the press, her struggle with addiction, and her determination to forge her own identity make her equally relevant to the lives of contemporary women. In writing this book, I hope that her voice is heard once more, by a new generation.

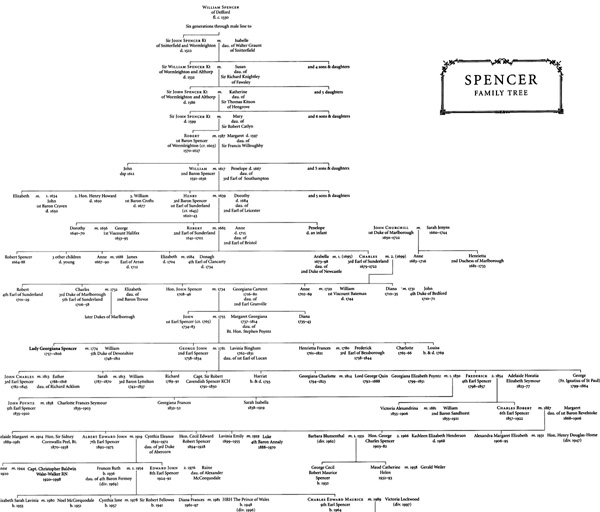

Family Trees

1Débutante1757–1774

‘I KNOW I was handsome … and have always been fashionable, but I do assure you,’ Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, wrote to her daughter at the end of her life, ‘our negligence and ommissions have been forgiven and we have been loved, more from our being free from airs than from any other circumstance.*1 Lacking airs was only part of her charm. She had always fascinated people. According to the retired French diplomat Louis Dutens, who wrote a memoir of English society in the 1780s and 1790s, ‘When she appeared, every eye was turned towards her; when absent, she was the subject of universal conversation.’2 Georgiana was not classically pretty, but she was tall, arresting, sexually attractive and extremely stylish. Indeed, the newspapers dubbed her the ‘Empress of Fashion’.

The famous Gainsborough portrait of Georgiana succeeds in capturing something of the enigmatic charm which her contemporaries found so compelling. However, it is not an accurate depiction of her features: her eyes were heavier, her mouth larger. Georgiana’s son Hart (short for Marquess of Hartington) insisted that no artist ever succeeded in painting a true representation of his mother. Her character was too full of contradictions, the spirit which animated her thoughts too quick to be caught in a single expression.

Georgiana Spencer was born at Althorp, outside Northampton, on 7 June 1757, the eldest child of the Earl and Countess Spencer.† She was a precocious and affectionate baby and the birth of her brother George, a year later, failed to diminish Lady Spencer’s infatuation with her daughter. Georgiana would always have first place in her heart, she confessed: ‘I will own I feel so partial to my Dear little Gee, that I think I never shall love another so well.’3 The arrival of a second daughter, Harriet, in 1761 did not alter Lady Spencer’s feelings. Writing soon after the birth, she dismissed Georgiana’s sister as a ‘little ugly girl’ with ‘no beauty to brag of but an abundance of fine brown hair’. The special bond between Georgiana and her mother endured throughout her childhood and beyond. They loved each other with a rare intensity. ‘You are my best and dearest friend,’ Georgiana told her when she was seventeen. ‘You have my heart and may do what you will with it.’4

By contrast, Georgiana – like her sister and brother – was always a little frightened of her father. He was not violent, but his explosive temper inspired awe and sometimes terror. ‘I believe he was a man of generous and amiable disposition,’ wrote his grandson, who never knew him. But his character had been spoiled, partly by almost continual ill-health and partly by his ‘having been placed at too early a period of his life in the possession of what then appeared to him inexhaustible wealth’. Georgiana’s father was only eleven when his own father died of alcoholism, leaving behind an estate worth £750,000 – roughly equivalent to £45 million today.* It was one of the largest fortunes in England and included 100,000 acres in twenty-seven different counties, five substantial residences, and a sumptuous collection of plate, jewels and old master paintings. Lord Spencer had an income of £700 a week in an era when a gentleman could live off £300 a year.

Georgiana’s earliest memories were of travelling between the five houses. She learnt to associate the change in seasons with her family’s move to a different location. During the ‘season’, when society took up residence ‘in town’ and parliament was in session, they lived in a draughty, old-fashioned house in Grosvenor Street. In the summer, when the stench of the cesspool next to the house and the clouds of dust generated by passing traffic became unbearable, they took refuge at Wimbledon Park, a Palladian villa on the outskirts of London. In the autumn they went north to their hunting lodge in Pytchley outside Kettering, and in the winter months, from November to March, they stayed at Althorp, the country seat of the Spencers for over 300 years.

When the diarist John Evelyn visited Althorp in the seventeenth century he described the H-shaped building as almost palatial, ‘a noble pile … such as may become a great prince’.5 He particularly admired the great saloon, which had been the courtyard of the house until one of Georgiana’s ancestors covered it over with a glass roof. To Lord and Lady Spencer it was the ballroom; to the children it was an indoor playground. On rainy days they would take turns to slide down the famous ten-foot-wide staircase or run around the first-floor gallery playing tag. From the top of the stairs, dominating the hall, a full-length portrait of Robert, first Baron Spencer (created 1603), gazed down at his descendants whose lesser portraits lined the ground floor.*

Georgiana was seven when the family moved their London residence to the newly built Spencer House in St James’s, overlooking Green Park. The length of time and sums involved in the building – almost £50,000 over seven years – reflected Lord Spencer’s determination to create a house worthy of his growing collection of classical antiquities. The travel writer and economist Arthur Young was among the first people to view the house when Lord Spencer opened it to the public. ‘I know not in England a more beautiful piece of architecture,’ he wrote, ‘superior to any house I have seen … The hangings, carpets, glasses, sofas, chairs, tables, slabs, everything, are not only astonishingly beautiful, but contain a vast variety.’6 Everything, from the elaborate classical façade to the lavishly decorated interior, so much admired by Arthur Young, reflected Lord Spencer’s taste. He was a noted connoisseur and passionate collector of rare books and Italian art. Each time he went abroad he returned with a cargo of paintings and statues for the house. His favourite room, the Painted Room, as it has always been called, was the first complete neo-classical interior in Europe.

The Spencers entertained constantly and were generous patrons. Spencer House was often used for plays and concerts and Georgiana grew up in an extraordinarily sophisticated milieu of writers, politicians and artists. After dinner the guests would sometimes be entertained by a soliloquy delivered by the actor David Garrick or a reading by the writer Laurence Sterne, who dedicated a section of Tristram Shandy to the Spencers. The house had been built not to attract artists, however, but to consolidate the political prestige and influence of the family. The urban palaces of the nobility encircled Westminster like satellite courts. They were deliberately designed to combine informal politics with a formal social life. A ball might fill the vast public rooms one night, a secret political meeting the next. Many a career began with a witty remark made in a drawing room; many a government policy emerged out of discussions over dinner. Jobs were discreetly sought, positions gained, and promises of support obtained in return. This was the age of the Whig oligarchy, when a handful of great landowning families sat in the cabinet, and owned or had a controlling interest in more than half the country’s electoral boroughs. Land conferred wealth, wealth conferred power, and power, in eighteenth-century terms, meant access to patronage, from lucrative government sinecures down to the local parish office worth £20 per annum.

Ironically, there was one condition attached to Lord Spencer’s inheritance: although he could sit in parliament he could not embark on a political career.* He retained great influence because he could use his wealth to support the government, but his political ambitions were thwarted. As a result he had no challenges to draw him out, and little experience of applying himself. He led a life dedicated to pleasure and, in time, the surfeit of ease took its toll. Lord Spencer became diffident and withdrawn. The indefatigable diarist Lady Mary Coke, a distant relation, once heard him speak in parliament and thought ‘as much as could be heard was very pretty, but he was extremely frightened and spoke very low’.7 The Duke of Newcastle awarded him an earldom in 1765 in recognition of his consistent loyalty. But Lord Spencer’s elevation to the peerage failed to prevent him from becoming more self-absorbed with each passing year. His friend Viscount Palmerston reflected sadly: ‘He seems to be a man whose value few people know. The bright side of his character appears in private and the dark side in public … it is only those who live in intimacy with him who know that he has an understanding and a heart that might do credit to any man.’8

Lady Spencer knew her husband could be generous and sensitive. Margaret Georgiana Poyntz, known as Georgiana, met John Spencer in 1754 when she was seventeen, and immediately fell in love with him. ‘I will own it,’ she confided to a friend, ‘and never deny it that I do love Spencer above all men upon Earth.’9 He was a handsome man then, with deep-set eyes and thin lips which curled in a cupid’s bow. His daughter inherited from him her unusual height and russet-coloured hair. When Lady Spencer first knew him he loved to parade in the flamboyant fashions of the French aristocracy. At one masquerade he made a striking figure in a blue and gold suit with white leather shoes topped with blue and gold roses.10

Georgiana’s mother had delicate cheekbones, auburn hair and deep brown eyes which looked almost black against her pale complexion. The fashion for arranging the hair away from the face suited her perfectly. It helped to disguise the fact that her eyes bulged slightly, a feature which she passed on to Georgiana. She was intelligent, exceptionally well read and, unusually for women of her day, she could read and write Greek as well as French and Italian. A portrait painted by Pompeo Batoni in 1764 shows her surrounded by her interests: in one hand she holds a sheaf of music – she was a keen amateur composer – near the other lies a guitar; there are books on the table and in the background the ruins of ancient Rome, referring to her love of all things classical. ‘She has so decided a character,’ remarked Lord Bristol, ‘that nothing can warp it.’11

Her father, Stephen Poyntz, had died when she was thirteen, leaving the family in comfortable but not rich circumstances. He had risen from humble origins – his father was an upholsterer – by making the best of an engaging manner and a brilliant mind. He began his career as a tutor to the children of Viscount Townshend and ended it a Privy Councillor to King George II. Accordingly, he brought up his children to be little courtiers like himself: charming, discreet and socially adept in all situations. Vice was tolerated so long as it was hidden. ‘I have known the Poyntzes in the nursery,’ Lord Lansdowne remarked contemptuously, ‘the Bible on the table, the cards in the drawer.’

‘Never was such a lover,’ remarked the prolific diarist and chronicler of her times Mrs Delany, who watched young John Spencer ardently court Miss Poyntz during the spring and summer of 1754. The following year, in late spring, the two families, the Poyntzes and the Spencers, made a week-long excursion to Wimbledon Park. There was no doubt in anyone’s mind about the outcome and yet Spencer was in an agony of anticipation throughout the visit. At the last moment, with the carriages waiting to leave, he drew her aside and blushingly produced a diamond and ruby ring. Inside the gold band, in tiny letters, were the words: ‘MON COEUR EST TOUT À TOI. GARDE LE BI EN POUR MOI.’*

The first years of their married life were happy. The Duke of Queensberry, known as ‘Old Q’, declared that the Spencers were ‘really the happiest people I ever saw in the marriage system’. They delighted in each other’s company and were affectionate in public as well as in private. In middle age, Lady Spencer proudly told David Garrick, ‘I verily believe that we have neither of us for one instant repented our lot from that time to this.’12 They had ‘modern’ attitudes both in their taste and in their attitude to social mores. Their daughter Harriet recorded an occasion when Lord Spencer took her to see some mummified corpses in a church crypt because ‘it is foolish and superstitious to be afraid of seeing dead bodies’.13 Another time he ‘bid us observe how much persecution encreased [the] zeal for the religion [of the sect] so oppressed, which he said was a lesson against oppression, and for toleration’.14