Полная версия

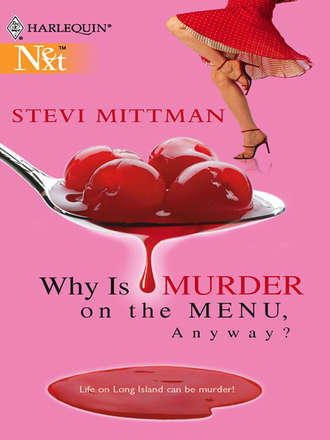

Why Is Murder On The Menu, Anyway?

“Well,” Drew says, “you might ask your friend tonight if he isn’t interested. I’m pretty certain he knew him.”

Howard is stunning in his navy sports jacket and his khaki shirt, which he wears open at the collar so that he is not overly formal, but still well-dressed. The man truly knows how to put himself together. He looks out of place in the parking lot that serves both the strip of stores and restaurants on Park Avenue in Rockville Centre and the local Long Island Railroad station. Spring is in the air, and there is just the slightest warm breeze, promising the summer to come. My skirt with the sequins scattered over the flowers catches the breeze and propels me toward Madison on Park, where Howard says that Madison wants to talk to me.

The restaurant is dim—usually a sign that they are hiding worn carpeting, frayed linens and a chipping paint job, but, maybe because of the soft music playing in the background, the place still manages to pull off a romantic air.

It’s warm, in that homey sort of way where you get the sense that people come here fairly often, but only as the default choice. Despite its reputation, it doesn’t look to me like the kind of place you’d celebrate a new job (unless you’re me and the job is redecorating the place), or that you’d take your boss if you wanted to impress him. It’s upscale, but just barely hanging on by a thread. It’s comfortable, sort of.

In fact, that’s what’s wrong with it. It’s not anything enough.

It’s one of those places you agree on when he doesn’t feel like Chinese and you don’t feel like Italian, and Thai sounds too exotic and a hamburger too ordinary. Judging from the diners, it’s nobody’s first choice, but everyone can agree on it.

Madison, her right index finger heavily bandaged, greets us at the door as though we are long-lost relatives from the old country. She is what my mother would call “on.” I think it has to do with being in her element.

“What a fiasco,” she says and laughs a tinny laugh. “Well, at least the publicity hasn’t hurt us any.” She shepherds us through the half-empty restaurant to a spot against the back wall. It’s apparent to me that Madison on Park can’t live on its six-year-old Zagat rating much longer.

A waiter appears and pulls the table out for me. I slide into the banquette while Howard takes the seat facing me and asks Madison how Nick is taking last night’s disappointment.

She says they’ll surely never forget it and looks down at her bandages. She leans into the table and says quietly, “If it didn’t hurt so damn much, I’d cut off another one just to keep the sympathy diners coming in.”

Howard looks just as appalled as I feel, and Madison seems to sense her mistake. She once again laughs her tinny laugh to signal she was only joking and then disappears toward the kitchen.

I pick up my menu, open it and am surprised by the offerings. The choices are exotic. The prices are through the roof. I’m thrilled because I now have a bead on what the restaurant needs. Forget homey. Forget comfortable. You don’t pay these kinds of prices just for the food, you pay them for atmosphere.

And if there’s one thing I know how to create, it’s ambience.

I close my eyes, imagining this place with chandeliers rather than high hats, fabric walls rather than paneling, a fabulous window treatment. When I open them, I catch the faintest glimpse of someone through the window, just now walking out of view. Though I didn’t see his face, I’d know that leather jacket anywhere. So when Howard asks me if there is anything I see that I want, I nearly choke on my water. When I can catch my breath I tell him, as I always do, to order for both of us.

Howard orders the inzimino, which he tells me is calamari, spinach, chickpeas and nero d’avola served on a crouton. I don’t have a clue what nero d’avola is, but I say, “and for me?” which tells him I’d only eat his choice at gunpoint, and even then I might not. He suggests the foie gras and braised duck terrine, and I give him my please take pity on me look. He orders me a tricolor salad and then goes on to order three different entrées of which he requests petit portions for us to share and taste. Like I would really touch a braised pork shank with pepperoncini and wild mushrooms over a ragout of root vegetables.

While he orders, I watch Drew Scoones pantomiming outside the window. The best I can tell, he’s asking me to go ahead and ask Howard something. I shake my head. Howard catches me, shifts around in his seat so that he can see out the window, and asks what I’m looking at since Drew is no longer in view.

I tell him the window treatment is dreadful. He turns back to me. Drew comes back into view. Howard turns for another look. Drew manages to disappear again.

If Drew wants to know what Howard knows, he can ask him himself. What does he think? That Howard is a murderer? As far as I know, Howard’s never done an illegal thing in his life—if you don’t count the turn he made against the light the night that Drew followed us and pulled him over to give him a ticket.

And that was entrapment.

And Howard is not duplicitous—except maybe the whole trolling thing on JDate when we were first going out. But I don’t count that since he thought he was flirting with me and not with my mother, who’d registered me without my knowledge or participation.

So what if he knew the Health Department Inspector? He’s a food critic. Shouldn’t he know the man who makes sure he isn’t going to get food poisoning doing his job?

“So, Teddi, about The Steak-Out…” he starts. “I wanted to ask you—” But Nick comes over, his chef’s hat askew, and interrupts him.

“Howard’s girl,” he says, nodding at me and grabbing up my hand to shake it. “Good to meet you again. Madison see you yet?” he asks, but he doesn’t wait for an answer. Instead he asks Howard if he can talk to him alone for a minute, apologizing to me as he asks.

Howard, looking horrified, says, “No,” really weirdly. Like just “no,” without any “sorry,” or “something wrong?” or anything. I remind myself that another of my New Year’s resolutions was to stop seeing perfectly ordinary things as suspicious. Just because Drew Scoones put a bug in my ear (or wherever he put it) is no reason to let my imagination run away with me.

“I have to powder my nose, anyway,” I say, putting my napkin beside my plate and coming to a stand.

Nick apologizes again and says he only needs a minute while Howard reaches out his hand to stop me from leaving the table. Drew is still watching, now from across the street, and I can just see relating this to him and listening to him guess that Howard’s credit card was refused.

I pat Howard’s hand and get up from the table. The layouts of most restaurants fall into two categories. Cheaper, funkier ones often have their restroom toward the side or front of the place. The ones that want to appear classier, more exclusive, have them in the back, near the kitchen, because they aren’t afraid of what a patron might see. The layout of Madison on Park and The Steak-Out are nearly identical—loos near the kitchen, only the placement of the Male/Female rooms are reversed.

Which explains why I am frozen in my tracks in front of the restroom doors, feeling slightly nauseated and just a trifle dizzy.

“Are you all right?” I hear someone say, and turn to find Madison standing beside me. “You look kind of green, dear.”

I assure her I’m fine, but my hand just won’t reach out and grasp the doorknob. I feel sweat break out on my upper lip.

“Shall I get Howard?” she asks, seemingly caught between leaving me to possibly fall down in a dead faint and wanting someone else to deal with it.

I explain about The Steak-Out and being the one to open the men’s room door and find the body.

“Oh, you poor thing,” she coos over me solicitously. Or, should I say, salaciously. She, like everyone else, no doubt wants the gory details. “So sad about Joe. Who would do a thing like that? In a men’s room, no less. Leave it to a man, right? I swear, it’s the sort of thing you see on television. A regular mob hit, or made to look like one, I’d say. So sad.”

“So you knew him?” I ask, wishing I could pull my antennae in. None of my business. None of my business.

Still…

“Don’t tell Nick,” she says, lowering her voice dramatically. “Especially now. But this was before I even knew Nick, anyway. Joe and I…we were kind of an item for a while. Not that anyone knew. We kept it hush-hush. I mean, a restaurateur and the health inspector. It could be misinterpreted.”

“You owned this restaurant before you knew Nick?” I ask.

“Not this one,” she says. “Another restaurant. In Boston, in fact. Nothing like this one. And I was just a chef, anyway. I’m embarrassed to even tell you the name.”

She can tell me who she slept with, but not where she used to cook. Howard always tells me that chefs take their knives to bed. Now I believe him.

My cell phone rings. It’s the theme from Home Alone, which means one of my kids is calling from home. I apologize to Madison, who didn’t even appear to notice, and I take the call. It’s Jesse, who tells me that his father wants to borrow my car. Only he doesn’t call him “my father.” He calls him “your ex-husband.”

Rio gets on the phone. Before he gets past “How ya doing?” I tell him he cannot borrow my car.

“You really get a kick out of busting my balls, don’t you? In front of our kids, too. You don’t even wanna know what I need it for?” he says like it’s an accusation.

I tell him I don’t. “Unless one of my children is bleeding on the floor and you need to take him or her to the hospital, you can’t borrow the car.”

“It’s something like that,” he says. “And I only need it for a couple of days.”

I ask him what he means by it’s something like that.

He says one of his kids needs to go the hospital.

“I’ll be right there,” I tell him, signaling to Madison that I’m sorry, waving to Howard that we’ve got to leave. He’s deep in conversation with Nick and I decide I can get home faster with Drew and his siren. I should never have left the kids alone. I am a terrible mother. I should be arrested for child abuse.

Only, then who’d raise my kids?

I dash out of the restaurant like a maniac, searching for Drew, while I try to get a straight answer out of Rio.

I should know better.

“Who is hurt?” I demand. Drew appears from nowhere.

“What’s happening?” he demands.

The kids, I mouth. “Rio, I swear to God I will kill you if you don’t tell me, this instant, who is hurt and how they are hurt.”

Drew hustles me toward his car.

“Nobody’s hurt,” Rio says. “I didn’t say anyone was hurt. Did I say anyone was hurt?”

I put up my hand to stop Drew, who looks pretty pale for a man who sees dead people on a daily basis. “If no one is hurt, why are you taking my kids to the hospital?”

“I didn’t say your kids,” Rio says. His voice changes like he’s cupping the phone. “I said mine.”

“What? My kids aren’t your kids?” I ask before I realize what he’s saying.

“I’m gonna be a father again,” he says. I lean against Drew’s car. My legs have turned to gummi worms. Relief? Jealousy? Drew leans into me the better to hear Rio’s news. “The kids are gonna have a new little sister, sometime in the next couple a days.”

“Put Jesse on the phone,” I tell Mr. High Sperm Count while Drew laughs at me and Howard comes charging toward us.

“Mom?” Jesse says, and my heart goes out to this middle child of mine who is always caught in the middle.

“Listen to me, Jesse,” I say as evenly as I can. “Go into my office. In my desk, in that little drawer behind the door that opens for the printer, is some money. Give your father fifty dollars and tell him to use it for a cab to take Marion to the hospital when the time comes. Do not, I repeat, do not, give him the keys to my car.”

Jesse asks if I’m sure he should give him the money and I tell him softly that we do not take out our anger at his dad on a pregnant lady and her new baby. Hell, how else is he going to learn to be a good man? A mensch? Surely not from his father.

When I hang up, the men at my side seem to have nothing to say.

“My ex is going to be a father again,” I say, trying to sound breezy about the whole thing. “What does that make me?”

“Mad?” Howard asks.

“Even crazier than usual?” Drew suggests.

“I mean, Marion is my kids’ stepmother, or will be if Rio ever bothers to marry her. But we’re already divorced, so what would his baby be to me?”

“A thorn in your side?” Howard says.

“A pain in the ass?” Drew suggests.

“I’m glad you two are so thoroughly enjoying yourselves. Too bad it’s at my expense.”

Both men stand around with their hands in their pockets as if they don’t want to touch this situation literally or figuratively.

Finally, Howard asks Drew what he’s doing here. Drew claims that he was hungry, saying that even cops eat, and somehow the three of us wind up back in Madison on Park like we’re the best of friends.

Nick comes by to tell us to order freely. Everything is on the house. He brings a bottle of wine, which Howard tries to decline as too generous, but Nick insists.

Drew, making some Everyman statement, orders a beer.

With some difficulty, Madison pulls up a chair and all of us reach to help her a moment too late. She waves away our belated attempts as if to say “It’s nothing,” and declines the offer to join us in any wine, our gazes connecting as she does. Then, as if brushing the moment aside, she asks me what I think of the decor.

I try to find something nice to say and mention the romantic air. Drew looks amused.

“You can be honest,” she says. “God knows, they’re always saying honesty is the best policy.”

“So, what kind of name is Madison, anyway?” Drew asks. I don’t know if he is somehow implying that the woman hasn’t come by the name honestly, or just making conversation. I never can tell exactly what Drew is up to, which is how I wound up in his bed in the first place.

Anyway, she explains that she was born on Madison Avenue to Yugoslavian immigrants. I want to say, “So there.”

I tell her the restaurant has good bones, but the colors are off, and so much more could be done for the place with very little expense. And then I tell her that I would be happy to do the work at cost since the restaurant would be a great showcase for my talents. I tell her that Bobbie and I are still establishing our credentials and that it would be worth it to us to give her a great deal.

“A win-win situation,” Howard calls it while Drew indicates that his phone is vibrating and that he has to go.

“Ask them about Joe Greco,” he whispers in my ear as he gets up to leave. I glare at him while he shakes hands with Howard and takes Madison’s uninjured left hand. “You take care now,” he tells her as she rises along with him and sees him out, greeting new diners at the door.

“So what did Nick want to talk to you about, anyway?” I ask Howard while he waxes on about braised remembrance farm greens, whatever they are.

“Wanted to tell me about the health inspector being murdered,” Howard says. “I told him I already knew from you.”

“Why did he want to tell you about Joe Greco?” I ask. Howard doesn’t ask me if that was the man’s name.

He just says that Nick always treats him like he’s “in the business,” what with him being a food critic and all and that I shouldn’t go reading anything into it, the way I always do. “It’s not like he had anything to do with it,” he adds.

“Fine,” I say, dropping it in favor of talking about decorating Madison on Park.

“Can you really keep the cost down?” he asks me. This from a man who is having caviar-encrusted salmon on the house.

“It doesn’t look like they’re hurting,” I tell him, imagining Scalamandré silks on the window with layer upon layer of passementerie.

Howard looks around the room. “Appearances,” he says, “can be deceiving.”

CHAPTER 4

Design Tip of the Day

“Family photos can personalize your space, but they have their place. Limit your office to two or three, and save your rogues’ gallery for a hallway or small wall where they can be studied in relation to one another and serve to reveal how you came to be who you are.”

—TipsFromTeddi.com

I hit “post” and the tip appears on my Web site. Unfortunately, the two photos that are supposed to accompany it disappear. If only it were that easy to dispose of a couple of the people in my life. And their baby-to-be.

Family, even ex-family, sure can make your life interesting. For example, there’s my mother, who certainly makes life…interesting.

And I wish Bobbie would stop laughing about what that mother of mine did, because she’s spitting soda on my kitchen counter and my laptop, and because what happened at my parents’ house is not really funny. But you be the judge. I stopped by my parents’ house to check on my mother—you know, see how she was doing after finding Joe Greco and all. She answered the door and told me that my father was “washing his hands.”

While I hit computer keys in an attempt to find what happened to the pictures of my bathroom wall and Bobbie’s husband, Mike’s, credenza, which are supposed to illustrate my point about family photos, Bobbie tells me she thinks that so far my story is “the first normal thing you’ve ever told me happened in your mom’s house.”

Of course, since it’s my mother’s house, it doesn’t stay normal for long. My father took forever, and it turned out he wasn’t in the bathroom, but in the kitchen, really washing his hands.

Bobbie whines that I already told her this part. She’s holding up earrings to her ears and checking out her reflection in the glass of my kitchen cabinets, seeking my opinion, which she will ultimately ignore. “Tell me again how your mother told him she bought him the ring.”

“And that he shouldn’t let me see it because I’m so poor and I’ll think she’s being extravagant?” I ask, copying and pasting the pictures back where they belong and indicating the dangly earrings over the studs while I tell the story. “It’s so totally my mother. So I tell my dad that she didn’t buy it, she stole it from a dead man. Which doesn’t help get the ring off his finger and now he’s desperate to get it off like it’s cursed or something. Only the harder he tries, the tighter it gets.”

“Windex,” Bobbie says in that matter-of-fact, doesn’t-everyone-know-this way she has. “They use it in jewelry shops when you can’t get the diamonds off your hand.” I tell her we could have used her at my mom’s house.

“Instead, we had to go to the emergency room because his finger was swelling up,” I tell her. “Four hours later, after my mother has made up half a dozen cock-and-bull stories for every nurse and physician in the hospital about how the ring was smuggled into the country by her Russian ancestors, he’s handing me the ring.”

“And he wasn’t furious with her?” Bobbie asks. I tell her we’ve all learned that there isn’t any point in being mad at my mother. It doesn’t bother her in the slightest and it just drives us insane.

“Anyway, now I’m the one who’s got to get rid of the thing,” I say, pushing Joe Greco’s diamond pinky ring across the kitchen counter toward Bobbie with one finger while I peruse the questions posted on my site—in the hopes that I can answer one of them. I’m amazed that people out there are actually seeking my advice. Especially when Bobbie opts for the diamond studs instead of the longer earrings.

“Sell it,” Bobbie says, flicking the ring back toward me as I settle on the question of how to remove blood stains from draperies. “You could use the money.”

I remind her it isn’t mine to sell and type in a question of my own. I hate to ask, but how does one get blood on the draperies in the first place? I know the right thing to do is to just turn it over to the police, but my mother’s had enough trouble with them, and then again, Drew is already calling it my murder. I push the ring back toward her and it dances off the counter onto the floor and caroms off the baseboard.

“But it would give you a good excuse to see him again,” Bobbie says while I stoop to pick it up off the floor.

I tell her that I’m afraid that is precisely how it will look. Like I took the ring so that I could “produce evidence” and get involved with him on a case again.

Frankly, if that didn’t seem so embarrassingly obvious, I’d consider it.

“And maybe it’s some family heirloom or something,” I say, though it looks like a pretty generic Zales sort of thing.

“Okay then, Miss Goody Two-Shoes, give it back to the dead guy, why don’t you?” Bobbie says as if she doesn’t care much one way or the other, while I type The best way to deal with blood stains on draperies is to take them to the dry cleaners and let a professional do it. However, if you are sure they are washable, you could try an enzyme presoak and then wash as usual. Good luck!

“Give it back? How?” I ask her, closing down Windows and shutting off the computer. “Put it in an envelope and mail it to heaven?”

“I don’t know,” Bobbie says. “Why don’t you just take it to his funeral and ask him if he still wants it.”

I don’t know what else there is to do but that. “Right. We have to give it back to him at the funeral.”

Bobbie chokes on her soda. “We?”

I tell her that if I’m going to put the ring on a dead man’s finger, the least she can do is come along as moral support.

She says she’ll bring bail money in her enormous new Michael Kors bag.

Four days later the police release the body and Bobbie and I traipse into Queens for Joe Greco’s funeral. Bobbie insists that I drive because she hates Queens Boulevard. “It’s city driving,” she claims. Somewhere in the Secret Handbook of Long Island Rules it explains when the Borough of Queens is the City (like when you have to drive through it) and when it’s not (like when you want to buy nice things—is there a Bloomingdale’s in Flushing, Queens? A Nordstrom’s in Astoria, Queens?).

In my purse, which sits on the floor of my Toyota by Bobbie’s feet, is Joe’s ring. Having had his ring for several days now, I’m on a first-name basis with Joe. Which is closer than I am to my mother, who isn’t talking to me because I’ve taken her booty. I keep telling her that the word has a different meaning these days, but since she isn’t talking to me she isn’t hearing me, either.

I know this whole thing is a mistake. But sometimes, even when you know something is going to go badly, there’s nothing to do but go ahead with it, so, despite all the misgivings, I join the line of cars waiting to turn into the parking lot at the Anthony Verderame Funeral Home in Flushing.

In front of me is a black Mercedes like Howard’s, only bigger. In front of that is a black Cadillac Esplanade. Behind me is a black sports car with a silver jaguar lunging for the tail of my dented red Toyota RAV4. Every other car appears to be a black Lincoln Town Car.

Bobbie and I exchange glances that question whether we could be any more conspicuous. The line crawls, and if our car is a tip-off that we don’t belong here, the preponderance of men in black suits with dark glasses heading for the funeral steps really cinches it.

“We should not do this,” Bobbie says emphatically. “This is a mistake.”

The line of cars turning into the lot has multiplied into two lanes and we are part of the inner one, next to the curb. We couldn’t leave if we wanted to. Which, despite the looks we are getting from the mourners, I don’t.

“At least we shouldn’t park here, so that we can make a quick getaway,” Bobbie says, and she has a point. Of course, there isn’t one available spot on the street as far as the eye can see.

I tell her she is worried about nothing. I don’t tell her that my heart is pounding so hard I can hardly breathe around it, that I am drenched from my armpits right down to my waist. I also don’t tell her that I still haven’t come up with a plan beyond getting in the door.