Полная версия

The Jesus Papers: Exposing the Greatest Cover-up in History

He took them to an antique dealer in Bethlehem, who began peddling them to various parties he thought might be interested. Even so, there is something of a mystery over the full number of scrolls found. Seven were produced and eventually sold to academic institutions, but it seems that several others were found and perhaps held back or passed into the hands of other dealers or private collectors. And at least one found its way to Damascus and, for a brief period, into the hands of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency.

At that time, the station chief of the CIA in Damascus was Middle Eastern expert Miles Copeland. He related to me that one day a “sly Egyptian merchant” came to the door of his building and offered him a rolled-up ancient text of the type we now know as a Dead Sea Scroll. They were, of course, unknown then, and Copeland was unsure if such battered documents were valuable or even in any way interesting. He certainly could not read Aramaic or Hebrew, but he knew that the head of the CIA in the Middle East, Kermit Roosevelt, who was based in Beirut, was an expert in these ancient languages and would probably be able to read it. He took the scroll onto the roof of the building in Damascus and, with the wind blowing pieces of it into the streets below, unrolled it and photographed it. He took, he said, about thirty frames, and even this was not enough to record the entire text, so we can assume that the text was quite substantial. He sent the photographs off to the CIA station in Beirut.13 And there they vanished. Searches of CIA holdings under the provisions of the U.S. Freedom of Information Act have failed to find them. Copeland recalls that he heard the text concerned Daniel—but he did not know whether it proved to be a standard text of the Old Testament book or a pesher, that is, a commentary on certain key passages from an Old Testament text, like the commentary appearing on several of the other scrolls found in the same cave. Somewhere out there in the clandestine antique underworld, this valuable text undoubtedly still remains.

The Dead Sea Scrolls that have been studied give us for the first time direct insight into this large and widespread group we’ve been contemplating here—this group who detested foreign domination, who were single-mindedly concerned with the purity of the high priest—and king—and who were totally dedicated to the observance of Jewish law. In fact, one of the many titles by which they referred to themselves was Oseh ha-Torah—the Doers of the Law.

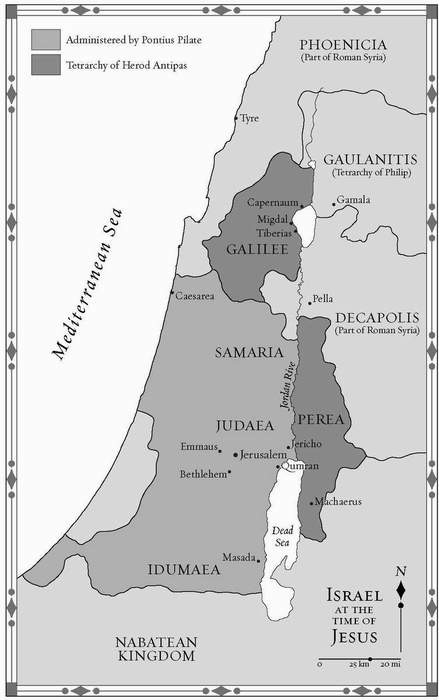

The Dead Sea Scrolls, it appears, provide original documents from the Zealots. For it was from their community that they emerged. What is also interesting is that, according to the archaeological evidence, Qumran, the site where many of the documents were found and where, at first sight, a Zealot center seems to have been established, was deserted during the time of Herod the Great, who had a palace just a few miles away in Jericho—the same palace that was burned down by “Zealots” after his death. It was thereafter that the occupation of Qumran began.14

The Dead Sea Scrolls were written directly by those who used them, and unusually for religious documents, they remain untouched by later editors or revisionists. What they tell us we can believe. And what they tell us is very interesting indeed. For one thing, they reveal a deep hatred of foreign domination that verges on the pathological, a hatred clearly fueled by a desire for revenge following many years of slaughter, exploitation, and disdain for the Jewish religion by an enemy they term the Kittim—this may be generic, but in the first century A.D. it clearly referred to the Romans. The War Scroll proclaims:

They shall act in accordance with all this rule on this day, when they are positioned opposite the camp of the Kittim. Afterwards, the priest will blow for them the trumpets…and the gates of battle shall open…The priests shall blow…for the attack. When they are at the side of the Kittim line, at throwing distance, each man will take up his weapons of war. The six priests shall blow the trumpets of slaughter with a shrill, staccato note to direct the battle. And the levites and all the throng with ram’s horns shall blow the battle call with a deafening noise. And when the sound goes out, they shall set their hand to finish off the severely wounded of the Kittim.15

So dreamed the Zealots, who loathed and detested the Romans: they would sooner die than serve the Kittim. They lived only for the day when a messiah would emerge from the Jewish people and lead them in a victorious war against the Romans and their puppet kings and high priests, erasing them from the face of the earth so that once again there might be a pure line of high priests and kings of the Line of David in Israel. In fact, they waited for two messiahs: the high priest and the king. The Rule of the Community, for example, speaks of the future “Messiahs of Aaron and Israel.”16 The Messiah of Aaron refers to the high priest; the Messiah of Israel denotes a king of the Line of David. Further scrolls mention the same figures. Provocatively, from our perspective, some scrolls, such as the Damascus Document, bring these two together and speak of one messiah, a “Messiah of Aaron and Israel.”17 They are revealing a figure who is both high priest and king of Israel.

All these texts make much of the necessity for the line of kings and high priests to be “pure,” that is, of the correct lineage. The Temple Scroll states: “From among your brothers you shall set over yourself a king; you shall not set a foreign man who is not your brother over yourself.”18

Both king and high priest were anointed and were thus a meshiha, a messiah. In fact, from as early as the second century B.C. the term “messiah” was used to name a legitimate king of Israel, one of the royal Line of David, who was expected to appear and to rule.19 This expectation was not, therefore, unique to the Zealots but ran as a strong undercurrent to the Old Testament and the Jewish faith of the second Temple period. It is more prevalent than one might think: it has been pointed out that “the Old Testament books were so edited that they emerge collectively as a messianic document.”20

The point is, of course, that the Jewish population of Judaea, at least, was expecting a messiah of the Line of David to appear. And with the hardships and horrors of the reign of Herod and the later Roman prefects, the time seemed to have come. The time for the messiah’s appearance had arrived, and that is why we needn’t be surprised when we discover that the rebel Zealot movement of Judas of Galilee and Zadok the Pharisee was, at its heart, messianic.21

Who then did they have in mind as the messiah?

The Dead Sea Scrolls provide a context for understanding the role of Jesus and the political machinations that would have featured behind his birth, marriage, and active role in this Zealot aspiration for victory. According to the Gospels, through his father, Jesus was of the Line of David; through his mother, he was of the line of Aaron the high priest (Matthew 1:1, 16; Luke 1:5, 36; 2:4). We suddenly get an understanding of his importance to the Zealot cause when we realize that because of his lineage he was heir to both lines. He was a “double” messiah; having inherited both the royal and priestly lines, he was a “Messiah of Aaron and Israel,” a figure, as we have seen, who was clearly noted in the Dead Sea Scrolls. And it would appear that he was widely seen as such. We can take as an expression of this fact Pilate’s supposedly ironic sign placed at the foot of the cross: This is Jesus the king of the Jews (Matthew 27, 37).22

As high priest and king—as Messiah of the Children of Israel (in Hebrew, bani mashiach)—Jesus would have been expected to lead the Zealots to victory. He would have been expected to oppose the Romans at every step and to hold tightly to the concepts of ritual purity that were so important to the Zealots. As the Zealot leader, he had a religious and political role to perform, and as it happens, there was a recognized way for him to perform it: the Old Testament prophet Zechariah had spoken of the arrival in Jerusalem of the king on a donkey (Zechariah 9:9-10). Jesus felt it necessary to fulfill this and other prophecies in order to gain public acceptance; indeed, the prophecy of Zechariah is quoted in the New Testament account of Matthew (21:5). So Jesus entered Jerusalem on a donkey. The point was not lost on the crowds who greeted his arrival: “Hosanna to the son of David,” they cried as they placed branches of trees and cloaks on the road for him to ride over in spontaneous gestures of acclaim.

Jesus had deliberately chosen his path. And he had been recognized as the king of the Line of David by the crowds of Jerusalem. The die was cast. Or so it seemed.

This deliberate acting out of Old Testament prophecy and its implications were discussed by Hugh Schonfield in his book The Passover Plot, which was first published in 1965; reissued many times since, it sold over six million copies in eighteen languages.23 It was a best-seller by anybody’s standards, and yet is today almost forgotten. Recent books do not even mention Schonfield’s work.

The matters he raised are certainly controversial but important; the custodians of the orthodox story are constantly trying to keep these alternative ideas out lest they shake the paradigm, lest they cause us to change our attitude toward the Gospels, the figure of Jesus, and the history of the times. Such lessons as Schonfield’s need to be repeated, generation after generation, until eventually they are supported by a weight of data so substantial that the paradigm has no alternative but to flip, causing us to approach our history from a very different perspective.

So many factors in Jesus’s life—the Zealot revolt, his birth to parents who were descendants of the Line of David and the Line of Aaron, respectively, the Zealot members of his immediate entourage, his deliberate entry into Jerusalem as king—should certainly have ensured Jesus’s place in history as the leader of the Jewish nation. But they didn’t. So what went wrong?

4 The Son of the Star

Simply put, the Zealot cause failed, utterly and disastrously. It was probably inevitable since, at its heart, it opposed the domination of the Romans, who were the greatest military power the Mediterranean world knew at the time. Although the natural course of the Zealot movement led it to oppose this domination openly and with all the force it could muster, it could never have won. That much was clear to all who looked even a little ahead.

It was evident that there were more Romans than Jews, and Roman power was centered upon an army of disciplined and well-trained professional soldiers who were not averse to feats of creative brutality if the situation demanded it—or if the soldier at hand just happened to feel like it. All this force was backed up by a widespread and formidable command of logistics supported by wellmaintained roads and ships, all of which were integrated into a structure that ensured troops and supplies were delivered in strength and on time.

Since the open emergence of the Zealot opposition in A.D. 6, a series of rulers—Roman governors and Jewish high priests alike—had managed, one way or another, to keep a kind of stability in Judaea.

JUDAEA, JESUS, AND CHRISTIANITY

Before 4 B.C. Birth of Jesus, according to Matthew’s Gospel (2:1). 4 B.C. Death of Herod the Great. A.D. 6 Birth of Jesus, according to Luke’s Gospel (2:1-7). Census of Quirinius, Governor of Syria. A.D. 27-28 Baptism of Jesus (traditional date) in the fifteenth year of the reign of Emperor Tiberius (Luke 3:1-23). A.D. 30 Crucifixion of Jesus, according to Catholic scholarship. c. A.D. 35 Following the marriage of Herod Antipas and Herodias in c. A.D. 34, John the Baptist is executed, following the evidence in Josephus. A.D. 36 Passover—crucifixion of Jesus, according to Matthew’s timetable. A.D. 36-37 Conversion of Paul on the road to Damascus. c. A.D. 44 Execution of James, the brother of Jesus. A.D. 50-52 Paul in Corinth. Writes his first letter (to the Thessalonians). A.D. 61 Paul in Rome under house arrest. c. A.D. 65 Paul supposedly executed. A.D. 66-73 War in Judaea. The Roman army under Vespasian invades Judaea. c. A.D. 55-120 Life of Tacitus, Roman historian and senator, who mentions Christ. c. A.D. 61-c. 114 Life of Pliny the Younger, who mentions Christ. c. A.D. 115 Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch, quotes from letters of Paul. c. A.D. 117-138 Suetonius, Roman historian, mentions “Chrestus.” c. A.D. 125 Earliest known example of a Christian gospel, John 18: 31-33, Rylands Papyrus, found in Egypt. c. A.D. 200 Oldest known fragment of Paul’s letters, Chester Beatty Papyrus, found in Egypt. c. A.D. 200 Oldest virtually complete gospel (John’s), Bodmer Papyrus, found in Egypt. A.D. 325 Council of Nicaea is convened by the Roman emperor Constantine. The divinity of Jesus is made official dogma by a vote of 217 to 3. A.D. 393-397 Council of Hippo, formalizing the New Testament, is finalized at Council of Carthage.THE FIRST CENTURY

4 B.C. Death of King Herod. A.D. 6 Zealot uprising, led by Judas of Galilee. A.D. 26 Pontius Pilate appointed prefect of Judaea (until A.D. 36). A.D. 36 Pontius Pilate recalled to Rome and exiled. A.D. 38 Anti-Jewish riots and killings in Alexandria are encouraged by the prefect Flaccus. A.D. 39 Herod Antipas exiled to the French Pyrenees. c. A.D. 44 James, the brother of Jesus, is executed. A.D. 46-48 Tiberius Alexander is prefect of Judaea. A.D. 64 Burning of Rome under Nero. Arrest of Christians. A.D. 66 Jewish general in Roman army, Tiberius Alexander, is prefect of Egypt. Sends in his troops to put down revolt in Alexandria. Several thousand Jews are killed. A.D. 66-73 War in Judaea. Roman army under Vespasian invades through Galilee. A.D. 67 Josephus, a Jewish military leader in Galilee, defects to the Roman side following a defeat. Writes Jewish histories (The Jewish War, A.D. 77-78; The Antiquities of the Jews, c. 94) while living in the imperial palace in Rome. A.D. 69 Vespasian is proclaimed emperor. Places his son Titus in charge of the army. Titus appoints Tiberius Alexander his chief of staff. A.D. 70 The Temple in Jerusalem is destroyed. Afterwards, Vespasian seeks out and executes all members of the royal Line of David. Jerusalem is renamed Aelia Capitolina, and all Jews are for bidden to enter the city. The Romans allow the Pharisee Johanan ben Zakkai to establish a religious school and the Sanhedrin at Jabneh, giving rise to rabbinical Judaism. (The school and the Sanhedrin will survive there until A.D. 132) A.D. 73 Masada is destroyed, and 960 Zealots commit suicide rather than be captured. Jewish temple of Onias in Egypt is closed.Both sides needed peace and the wealth that arose from it—conflict never plants seeds or grows crops, and idle land never produces food or money for the farmers, nor taxes for the rulers—and Rome relied upon Judaea for the forty talents it produced each year for the Roman treasury (the approximate equivalent of 3,750 pounds of silver).1 Through careful political husbandry, this unstable balance had lasted for half of the century. And then suddenly it all fell to pieces.

A group of anti-Roman priests in the Temple in Jerusalem decided to stop non-Jews from giving offerings. This cessation of the customary daily sacrifices performed for Caesar and for Rome in the Temple was a direct and abrupt challenge to the emperor. There was no turning back. The Zealots and the anti-Roman priests had led their people across the threshold of the doorway to hell. As Josephus reports, war against Rome was inevitable because of this act. The Zealots, in their misplaced ambition, thought that they would recover control of their nation, but so great was their loss that all such hope was to vanish for nearly two thousand years.

Fighting first erupted in A.D. 66 in the coastal city of Caesarea. Attempts to calm the situation were futile in the face of the frustration and hatred that had fueled the attacks. The Zealots had been waiting for this day, and now they had it. For them, tomorrow had finally come. Thousands were killed: Zealots took the fortress of Masada on the Dead Sea; others took over the lower city of Jerusalem and the Temple, burning down the palace of King Agrippa and that of the high priest. They also burned the official records office.

Leaders emerged from within the Jewish ranks: in Jerusalem the son of the high priest had been in charge. Then Judas of Galilee’s son appeared in Masada and looted the armory before returning to Jerusalem like a king, clothed in royal robes, to take over the palace. The official high priest was murdered.

At first, unprepared for such a catastrophic outpouring of hatred toward them, the Romans were readily beaten. The governor of Syria, Cestius Gallus, marched into Judaea from his capital in Antioch at the head of the Twelfth Legion. After destroying many communities and towns, his army besieged Jerusalem. But he was driven off with very heavy losses, including the commander of the Sixth Legion and a Roman tribune. Cestius himself seems to have escaped only by the speed of his retreat. In the debacle, the Zealots seized a great deal of weapons and money. Despite this show of strength, many prescient Jews fled Judaea, as they knew the situation could only get worse.

Judea and Galilee

And they were right: the Romans withdrew, but only to gather their strength. They were to return with brutality and vengeance. Meanwhile, in the absence of the Roman overlords, the Zealots regrouped too. They elected commanders for the various regions, raised troops, and began to train them in Roman military techniques and formations. The first fighting was to be in Galilee, where Josephus—yet to become the historian and friend of the Romans—was commander of the Zealot forces.

The Roman emperor Nero was outraged by the eruption of revolt in Judaea and ordered a respected army veteran, Vespasian, to take charge of regaining control over the country. Vespasian sent his son, Titus, to Alexandria to get the Fifteenth Legion. Vespasian himself marched down from Syria with the Fifth and Tenth Legions, together with twenty-three cohorts of auxiliaries—around eighteen thousand cavalry and infantry.

Vespasian and Titus met in the Syrian port of Ptolemais (now Akko) and, uniting their forces, moved inland, across the border into Galilee. Josephus was caught in his stronghold, Jotapata (now Yodefat), midway between Haifa and the Sea of Galilee. After a forty-seven-day siege, Galilee fell. Josephus escaped but was soon captured, surrendering to a high-ranking Roman officer, a tribune called Nicanor. Josephus describes him as an old friend and in almost the same breath reveals that he was himself “a priest and a descendent of priests.”2 In other words, Josephus was no Galilean hothead but rather a member of the Jerusalem aristocracy with strong links to the Roman administration.

Immediately after his capture, Josephus was imprisoned by the commander, Vespasian. But Josephus, in an action that clearly revealed his high-level association with the Romans, asked for a private meeting. Vespasian obliged, asking all but Titus and two friends to leave them. One of those two was probably Titus’s military chief of staff, Tiberius Alexander, who was Jewish and a nephew of the famous philosopher Philo of Alexandria.3 Tiberius Alexander had his own reasons for this meeting, which we shall see. What ensued was clearly a bit of well-contrived theater, with Josephus and Tiberius Alexander each playing a prominent part.

“You suppose, sir,” Josephus addressed Vespasian, clearly aware that this was a pivotal moment in his life and that the next few minutes would determine his future, “that in capturing me you have merely secured a prisoner, but I come as a messenger of the greatness that awaits you.” He explained, to give added importance to his words, that he was “sent by God Himself,” and then continued,

You, Vespasian, are Caesar and Emperor…you are master not only of me, Caesar, but of land and sea and all the human race; and I ask to be kept in closer confinement as my penalty if I am taking the name of God in vain.

Of course, with Nero still ruling in Rome, what Josephus was suggesting was high treason. But Vespasian, according to Josephus—and we should remember that he was writing this in Vespasian’s palace in Rome long after these events—was already thinking along these dangerous lines. Vespasian was reportedly skeptical of Josephus’s claims at first—and he should also have been outraged at the treason uttered against his emperor and should have ordered Josephus to be executed immediately. Yet he did not. In his book, Josephus provides a reason: “God was already awakening in him imperial ambitions and foreshadowing the sceptre by other portents.”4

This talk of “the sceptre,” meaning royal status, reveals a link to a crucial prophecy of “the Star”—referring to the expected messianic leader—which was, as stated earlier, the catalyst for the outbreak of war. References to “the Star” and the “sceptre” were contained in a prophecy made by Balaam the seer, as reported in the Old Testament. Balaam proclaimed his oracle:

I see him…I behold him—but not close at hand. A star from Jacob takes the leadership. A sceptre arises from Israel. (Numbers 24:17)

This “star from Jacob” clearly establishes that the messianic leader was expected to be born of the Line of David. Josephus states explicitly that this prophecy was the cause for the timing of the violence:

Their chief inducement to go to war was an equivocal oracle also found in their sacred writings, announcing that at that time a man from their country would become monarch of the whole world.

It was this prophecy that Josephus told to Vespasian. He also no doubt added—but didn’t reveal in the report of his meeting with the Roman commander—that the Zealots in Jerusalem took this “to mean the triumph of their own race.” They were certain that they would win in their war against the Romans because of this very religious oracle. But, Josephus adds later in his book, they were “wildly out in their interpretation. In fact,” he states bluntly and obsequiously, “the oracle pointed to the accession of Vespasian; for it was in Judaea he was proclaimed emperor.”5