Полная версия

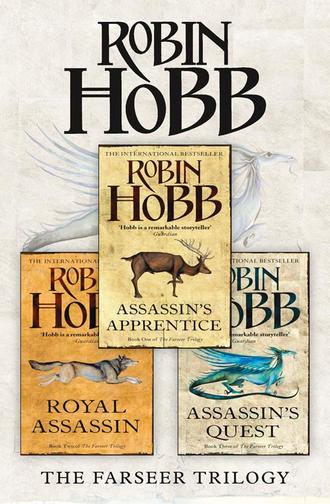

The Complete Farseer Trilogy: Assassin’s Apprentice, Royal Assassin, Assassin’s Quest

Somehow I survived the day, though the memory of how fades into a blessedly vague haze. I remember how sore I was when she finally dismissed us; how the others raced up the path and back to the keep while I trailed dismally behind them, berating myself for ever coming to the King’s attention. It was a long climb to the keep, and the hall was crowded and noisy. I was too weary to eat much. Stew and bread, I think, were all I had, and I had left the table and was limping toward the door, thinking only of the warmth and quiet of the stables, when Brant again accosted me.

‘Your chamber is ready,’ was all he said.

I shot a desperate look at Burrich, but he was engaged in conversation with the man next to him. He didn’t notice my plea at all. So once more I found myself following Brant, this time up a wide flight of stone steps, into a part of the keep I had never explored.

We paused on a landing, and he took up a candelabrum from a table there and kindled its tapers. ‘Royal family lives down this wing,’ he casually informed me. ‘The King has a bedroom big as the stable down at the end of this hallway.’

I nodded, blindly believing all he told me, though I later discovered that an errand boy such as Brant would never have penetrated the royal wing. That would be for more important lackeys. Up another flight he took me, and again paused. ‘Visitors get rooms here,’ he said, gesturing with the light so that the wind of his motion set the flames to streaming. ‘Important ones, that is.’

And up another flight we went, the steps perceptibly narrowing from the first two. At the next landing we paused again, and I looked with dread up an even narrower and steeper flight of steps. But Brant did not take me that way. Instead we went down this new wing, three doors down, and then he slid a latch on a plank door and shouldered it open. It swung heavily and not smoothly. ‘Room hasn’t been used in a while,’ he observed cheerily. ‘But now it’s yours and you’re welcome to it.’ And with that he set the candelabrum down on a chest, plucked one candle from it and left. He pulled the heavy door closed behind him as he went, leaving me in the semi-darkness of a large and unfamiliar room.

Somehow I refrained from running after him or opening the door. Instead, I took up the candelabrum and lit the wall sconces. Two other sets of candles set the shadows writhing back into the corners. There was a fireplace with a pitiful effort at a fire in it. I poked it up a bit, more for light than for heat, and set to exploring my new quarters.

They consisted of a simple square room with a single window. Stone walls, of the same stone as that under my feet, were softened only by a tapestry hung on one wall. I held my candle high to study it, but could not illuminate much. I could make out a gleaming and winged creature of some sort, and a kingly personage in supplication before it. I was later informed it was King Wisdom being befriended by the Elderling. At the time it seemed menacing to me. I turned aside from it.

Someone had made a perfunctory effort at freshening the room. There was a scattering of clean reeds and herbs on the floor, and the feather bed had a fat, freshly shaken look to it. The two blankets on it were of good wool. The bed curtains had been pulled back and the chest and bench that were the other furnishings had been dusted. To my inexperienced eyes, it was a rich room indeed. A real bed, with coverings and hangings about it, and a bench with a cushion, and a chest to put things in were more furniture than I could recall having to myself before. There was also the fireplace, that I boldly added another piece of wood to, and the window, with an oak seat before it, shuttered now against the night air, but probably looking out over the sea.

The chest was a simple one, cornered with brass fittings. The outside of it was dark, but when I opened it, the interior was light-coloured and fragrant. Inside I found my limited wardrobe, brought up from the stables. Two nightshirts had been added to it, and a woollen blanket was rolled up in the corner of the chest. That was all. I took out a nightshirt and closed the chest.

I set the nightshirt down on the bed, and then clambered up myself. It was early to be thinking of sleep, but my body ached and there seemed nothing else for me to do. Down in the stable room by now Burrich would be sitting and drinking and mending harness or whatever. There would be a fire in the hearth, and the muffled sounds of horses as they shifted in their stalls below. The room would smell of leather and oil and Burrich himself, not dank stone and dust. I pulled the nightshirt over my head and nudged my clothes to the foot of the bed. I nestled into the feather bed; it was cool and my skin stood up in goosebumps. Slowly my body heat warmed it and I began to relax. It had been a full and strenuous day. Every muscle I possessed seemed to be both aching and tired. I knew I should rise once more, to put the candles out, but I could not summon the energy. Nor the will-power to blow them out and let a deeper darkness flood the chamber. So I drowsed, half-lidded eyes watching the struggling flames of the small hearthfire. I wished idly for something else, for any situation that was neither this forsaken chamber nor the tenseness of Burrich’s room. For a restfulness that perhaps I had once known somewhere else but could no longer recall. And so I drowsed into an oblivion.

FOUR

Apprenticeship

A story is told of King Victor, he who conquered the inland territories that became eventually the Duchy of Farrow. Very shortly after adding the lands of Sand-sedge to his rulings, he sent for the woman who would, had Victor not conquered her land, have been the Queen of Sandsedge. She travelled to Buckkeep in much trepidation, fearing to go, but fearing more the consequences to her people if she appealed to them to hide her. When she arrived, she was both amazed and somewhat chagrined that Victor intended to use her, not as a servant, but as a tutor to his children, that they might learn both the language and customs of her folk. When she asked him why he chose to have them learn of her folk’s ways, he replied, ‘A ruler must be ruler of all his people, for one can only rule what one knows.’ Later, she became the willing wife of his eldest son, and took the name Queen Graciousness at her coronation.

I awoke to sunlight in my face. Someone had entered my chamber and opened the window shutters to the day. A basin, cloth and jug of water had been left on top of the chest. I was grateful for them, but not even washing my face refreshed me. Sleep had left me sodden and I recall feeling uneasy that someone could enter my chamber and move freely about without awakening me.

As I had guessed, the window looked out over the sea, but I didn’t have much time to devote to the view. A glance at the sun told me that I had overslept. I flung on my clothes and hastened down to the stables without pausing for breakfast.

But Burrich had little time for me that morning. ‘Get back up to the keep,’ he advised me. ‘Mistress Hasty already sent Brant down here to look for you. She’s to measure you for clothing. Best go find her quickly; she lives up to her name, and won’t appreciate your upsetting her morning routine.’

My trot back up to the keep reawakened all my aches of the day before. Much as I dreaded seeking out this Mistress Hasty and being measured for clothing I was certain I didn’t need, I was relieved not to be on horseback again this morning.

After querying my way up from the kitchens, I finally found Mistress Hasty in a room several doors down from my bedchamber. I paused shyly at the door and peered in. Three tall windows were flooding the room with sunlight and a mild salt breeze. Baskets of yarn and dyed wool were stacked against one wall, while a tall shelf on another wall held a rainbow of cloth goods. Two young women were talking over a loom, and in the far corner a lad not much older than I was rocking to the gentle pace of a spinning-wheel. I had no doubt that the woman with her broad back to me was Mistress Hasty.

The two young women noticed me and paused in their conversation. Mistress Hasty turned to see where they stared, and a moment later I was in her clutches. She didn’t bother with names or explaining what she was about. I found myself up on a stool, being turned and measured and hummed over, with no regard for my dignity or indeed my humanity. She disparaged my clothes to the young women, remarked very calmly that I quite reminded her of young Chivalry, and that my measurements and colouring were much the same as his had been when he was my age. She then demanded their opinions as she held up bolts of different goods against me.

‘That one,’ said one of the loom-women. ‘That blue quite flatters his darkness. It would have looked well on his father. Quite a mercy that Patience never has to see the boy. Chivalry’s stamp is much too plain on his face to leave her any pride at all.’

And as I stood there, draped in woolgoods, I heard for the first time what every other person in Buckkeep knew full well. The weaving-women discussed in detail how the word of my existence reached Buckkeep and Patience long before my father could tell her himself, and of the deep anguish it caused her. For Patience was barren, and though Chivalry had never spoken a word against her, all guessed how difficult it must be for an heir such as he to have no child eventually to assume his title. Patience took my existence as the ultimate rebuke, and her health, never sound after so many miscarriages, completely broke along with her spirit. It was for her sake as well as for propriety that Chivalry had given up his throne, and taken his invalid wife back to the warm and gentle lands that were her home province. Word was that they lived well and comfortably there, that Patience’s health was slowly mending, and that Chivalry, substantially quieter a man than he had been before, was gradually learning stewardship of his vineyard-rich valley. A pity that Patience blamed Burrich as well for Chivalry’s lapse in morals, and had declared she could no longer abide the sight of him. For between the injury to his leg and Chivalry’s abandonment of him, old Burrich just wasn’t the man he had been. Was a time when no woman of the keep walked quickly past him; to catch his eye was to make yourself the envy of nearly anyone old enough to wear skirts. And now? Old Burrich, they called him, and him still in his prime – so unfair, as if any manservant had any say over what his master did. But it was all to the good anyway, they supposed. And didn’t Verity, after all, make a much better King-in-Waiting than had Chivalry? So rigorously noble was Chivalry that he made all others feel slatternly and stingy in his presence; he’d never allowed himself a moment’s respite from what was right, and while he was too chivalrous to sneer at those who did, one always had the feeling that his perfect behaviour was a silent reproach to those with less self-discipline. Ah, but then here was the bastard, now, though, after all those years, and well, here was the proof that he hadn’t been the man he’d pretended to be. Verity, now there was a man among men, a king folk could look to and see as royalty. He rode hard, and soldiered alongside his men, and if he was occasionally drunk or had at times been less than discreet, well, he owned up to it, honest as his name. Folk could understand a man like that, and follow him.

To all this I listened avidly, if mutely, while several fabrics were held against me, debated and selected. I gained a much deeper understanding of why the keep children left me to play alone. If the women considered that I might have thoughts or feelings about their conversation, they showed no sign of it. The only remark I remember Mistress Hasty making to me specifically was that I should take greater care in washing my neck. Then Mistress Hasty shooed me from the room as if I were an annoying chicken, and I found myself finally heading to the kitchens for some food.

That afternoon I was back with Hod, practising until I was sure my stave had mysteriously doubled its weight. Then food, and bed, and up again in the morning and back to Burrich’s tutelage. My learning filled my days, and any spare time I found was swallowed up with the chores associated with my learning, whether it was tack-care for Burrich, or sweeping the armoury and putting it back in order for Hod. In due time I found not one, or even two, but three entire sets of clothing, including stockings, set out one afternoon on my bed. Two were of fairly ordinary stuff, in a familiar brown that most of the children my age seemed to wear, but one was of thin blue cloth, and on the breast was a buck’s head, done in silver thread. Burrich and the other men-at-arms wore a leaping buck as their emblem. I had only seen the buck’s head on the jerkins of Regal and Royal. So I looked at it and wondered, but wondered too, at the slash of red stitching that cut it diagonally, marching right over the design.

‘It means you’re a bastard,’ Burrich told me bluntly when I asked him about it. ‘Of acknowledged royal blood, but a bastard all the same. That’s all. It’s just a quick way of showing you’ve royal blood, but aren’t of the true line. If you don’t like it, you can change it. I am sure the King would grant it. A name and a crest of your own.’

‘A name?’

‘Certainly. It’s a simple enough request. Bastards are rare in the noble houses, especially so in the King’s own. But they aren’t unheard of.’ Under the guise of teaching me the proper care of a saddle, we were going through the tack room, looking over all the old and unused tack. Maintaining and salvaging old tack was one of Burrich’s odder fixations. ‘Devise a name and a crest for yourself, and then ask the King …’

‘What name?’

‘Why, any name you like. This looks as if it’s ruined; someone put it away damp and it mildewed. But we’ll see what we can do with it.’

‘It wouldn’t feel real.’

‘What?’

He held an armload of smelly leather out toward me. I took it.

‘A name I just put to myself. It wouldn’t feel as if it was really mine.’

‘Well, what do you intend to do, then?’

I took a breath. ‘The King should name me. Or you should.’ I steeled myself. ‘Or my father. Don’t you think?’

Burrich frowned. ‘You get the most peculiar notions. Just think about it yourself for a while. You’ll come up with a name that fits.’

‘Fitz,’ I said sarcastically, and I saw Burrich clamp his jaw.

‘Let’s just mend this leather,’ he suggested quietly.

We carried it to his workbench and started wiping it down. ‘Bastards aren’t that rare,’ I observed. ‘And in town, their parents name them.’

‘In town, bastards aren’t so rare,’ Burrich agreed after a moment. ‘Soldiers and sailors whore around. It’s a common way for common folk. But not for royalty. Or for anyone with a bit of pride. What would you have thought of me, when you were younger, if I’d gone out whoring at night, or brought women up to the room? How would you see women now? Or men? It’s fine to fall in love, Fitz, and no one begrudges a young woman or man a kiss or two. But I’ve seen what it’s like down to Bingtown. Traders bring pretty girls or well-made youths to the market like so many chickens or potatoes. And the children they end up bearing may have names, but they don’t have much else. And even when they marry, they don’t stop their … habits. If ever I find the right woman, I’ll want her to know I won’t be looking at another. And I’ll want to know all my children are mine.’ Burrich was almost impassioned.

I looked at him miserably. ‘So what happened with my father?’

He looked suddenly weary. ‘I don’t know, boy. I don’t know. He was young, just twenty or so. And far from home, and trying to shoulder a heavy burden. Those are neither reasons nor excuses. But it’s as much as either of us will ever know.’

And that was that.

My life went round in its settled routine. There were evenings that I spent in the stables, in Burrich’s company, and more rarely, evenings that I spent in the Great Hall when some travelling minstrel or puppet show arrived. Once in a great while, I could slip out for an evening down in town, but that meant paying the next day for missed sleep. Afternoons were inevitably spent with some tutor or instructor. I came to understand that these were my summer lessons, and that in winter I would be introduced to the kind of learning that came with pens and letters. I was kept busier than I had ever been in my young life. But despite my schedule, I found myself mostly alone.

Loneliness.

It found me every night as I vainly tried to find a small and cosy spot in my big bed. When I had slept above the stables in Burrich’s rooms, my nights had been muzzy, my dreams heathery with the warm and weary contentment of the well-used animals that slept and shifted and thudded in the night below me. Horses and dogs dream, as anyone who has ever watched a hound yipping and twitching in dream pursuit knows. Their dreams had been like the sweet-rising waft from a baking of good bread. But now, isolated in a room walled with stone, I finally had time for all those devouring, aching dreams that are the portion of humans. I had no warm dam to cosy against, no sense of siblings or kin stabled nearby. Instead I would lie awake and wonder about my father and my mother, and how both could have dismissed me from their lives so easily. I heard the talk that others exchanged so carelessly over my head, and interpreted their comments in my own terrifying way. I wondered what would become of me when I was grown and old King Shrewd dead and gone. I wondered, occasionally, if Molly Nosebleed and Kerry missed me, or if they accepted my sudden disappearance as easily as they had accepted my coming. But mostly I ached with loneliness, for in all that great keep, there were none I sensed as friend. None save the beasts, and Burrich had forbidden me to have any closeness with them.

One evening I had gone wearily to bed, only to torment myself with my fears until sleep grudgingly pulled me under. Light in my face awoke me, but I came awake knowing something was wrong. I hadn’t slept long enough, and this light was yellow and wavering, unlike the whiteness of the sunlight that usually spilled in my window. I stirred unwillingly and opened my eyes.

He stood at the foot of my bed, holding aloft a lamp. This in itself was a rarity at Buckkeep, but more than the buttery light from the lamp held my eyes. The man himself was strange. His robe was the colour of undyed sheep’s wool that had been washed, but only intermittently and not recently. His hair and beard were about the same hue and their untidiness gave the same impression. Despite the colour of his hair, I could not decide how old he was. There are some poxes that will scar a man’s face with their passage. But I had never seen a man marked as he was, with scores of tiny pox scars, angry pinks and reds like small burns, and livid even in the lamp’s yellow light. His hands were all bones and tendons wrapped in papery white skin. He was peering at me, and even in the lamplight his eyes were the most piercing green I had ever seen. They reminded me of a cat’s eyes when it is hunting; the same combination of joy and fierceness. I pulled my quilt up higher under my chin.

‘You’re awake,’ he said. ‘Good. Get up and follow me.’

He turned abruptly from my bedside and walked away from the door, to a shadowed corner of my room between the hearth and the wall. I didn’t move. He glanced back at me, held the lamp higher. ‘Hurry up, boy,’ he said irritably and rapped the stick he leaned on against my bed post.

I got out of bed, wincing as my bare feet hit the cold floor. I reached for my clothes and shoes, but he wasn’t waiting for me. He glanced back once, to see what was delaying me, and the piercing look was enough to make me drop my clothes and quake.

I followed, wordlessly, in my nightshirt, for no reason I could explain to myself, except that he had suggested it. I followed him to a door that had never been there, and up a narrow flight of winding steps that were lit only by the lamp he held above his head. His shadow fell behind him and over me, so that I walked in a shifting darkness, feeling each step with my feet. The stairs were cold stone, worn and smooth and remarkably even. And they went up, and up, and up, until it seemed to me that we had climbed past the height of any tower the keep possessed. A chill breeze flowed up those steps and up my nightshirt, shrivelling me with more than mere cold. And we went up, and then finally he was pushing open a substantial door that nonetheless moved silently and easily. We entered a chamber.

It was lit warmly by several lamps, suspended from an unseen ceiling on fine chains. The chamber was large, certainly three times the size of my own. One end of it beckoned me. It was dominated by a massive wooden bed-frame fat with feather mattresses and cushions. There were carpets on the floor, overlapping one another with their scarlets and verdant greens and blues both deep and pale. There was a table made of wood the colour of wild honey, and on it sat a bowl of fruits so perfectly ripe that I could smell their fragrances. Parchment books and scrolls were scattered about carelessly as if their rarity were of no concern. All three walls were draped with tapestries that depicted open, rolling country with wooded foothills in the distance. I started toward it.

‘This way,’ said my guide, and relentlessly led me to the other end of the chamber.

Here was a different spectacle. A stone slab of a table dominated it, its surface much stained and scorched. Upon it were various tools, containers and implements, a scale, a mortar and pestle, and many things I couldn’t name. A fine layer of dust overlay much of it, as if projects had been abandoned in mid-course, months or even years ago. Beyond the table was a rack which held an untidy collection of scrolls, some edged in blue or gilt. The scent of the room was at once pungent and aromatic; bundles of herbs were drying on another rack. I heard a rustling and caught a glimpse of movement in a far corner, but the man gave me no time to investigate. The fireplace that should have warmed this end of the room gaped black and cold. The old embers in it looked damp and settled. I lifted my eyes from my perusal to look at my guide. The dismay on my face seemed to surprise him. He turned from me and slowly surveyed the room himself. He considered it for a bit, and then I sensed an embarrassed disgruntlement from him.

‘It is a mess. More than a mess, I suppose. But, well. It’s been a while, I suppose. And longer than a while. Well. It’s soon put to rights. But first, introductions are in order. And I suppose it is a bit nippy to be standing about in just a nightshirt. This way, boy.’

I followed him to the comfortable end of the room. He seated himself in a battered wooden chair that was over-draped with blankets. My bare toes dug gratefully into the nap of a woollen rug. I stood before him, waiting, as those green eyes prowled over me. For some minutes the silence held. Then he spoke.

‘First, let me introduce you to yourself. Your pedigree is written all over you. Shrewd chose to acknowledge it, for all his denials wouldn’t have sufficed to convince anyone otherwise.’ He paused for an instant, and smiled as if something amused him. ‘A shame Galen refuses to teach you the Skill; but years ago, it was restricted, for fear it would become too common a tool. I’ll wager if old Galen were to try to teach you, he’d find you apt. But we have no time to worry about what won’t happen.’ He sighed meditatively, and was silent for a moment. Abruptly he went on, ‘Burrich’s shown you how to work, and how to obey. Two things that Burrich himself excels at. You’re not especially strong, or fast, or bright. Don’t think you are. But you’ll have the stubbornness to wear down anyone stronger, or faster or brighter than yourself. And that’s more of a danger to you than to anyone else. But that is not what is now most important about you.

‘You are the King’s man now. And you must begin to understand, now, right now, that that is the most important thing about you. He feeds you, he clothes you, he sees you are educated. And all he asks in return, for now, is your loyalty. Later he will ask your service. Those are the conditions under which I will teach you. That you are the King’s man, and loyal to him completely. For if you are otherwise, it would be too dangerous to educate you in my art.’ He paused and for a long moment we simply looked at one another. ‘Do you agree?’ he asked, and it was not a simple question but the sealing of a bargain.