Полная версия

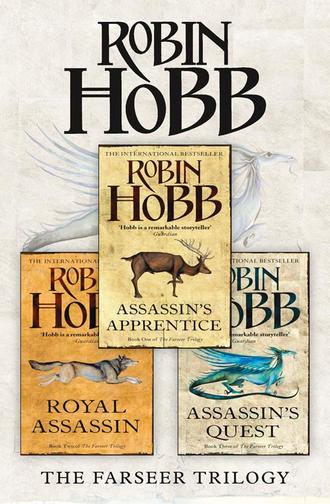

The Complete Farseer Trilogy: Assassin’s Apprentice, Royal Assassin, Assassin’s Quest

All of the stealthy arcane knowledge Chade had given me, all of Hod’s brutally elegant strategies for fighting two or more opponents, went to the wind. For as the first two stepped into my range, I felt the tiny warmth that was Smithy ebbing in my grasp. ‘Smithy!’ I whispered, a desperate plea that he somehow stay with me. I all but saw a tail tip stir in a last effort at a wag. Then the thread snapped and the spark blinked out. I was alone.

A black flood of strength surged through me like a madness. I stepped out, thrust the end of my staff deep into a man’s face, drew it quickly back, and continued a swing that went through the woman’s lower jaw. Plain wood sheared the lower half of her face away, so forceful was my blow. I whacked her again as she fell, and it was like hitting a netted shark with a fish-bat. The third drove into me solidly, thinking, I suppose, to be inside my staff’s range. I didn’t care. I dropped my stick and grappled with him. He was bony and he stank. I drove him onto his back, and his expelled breath in my face stank of carrion. Fingers and teeth, I tore at him, as far from human as he was. They had kept me from Smithy as he was dying. I did not care what I did to him so long as it hurt him. He reciprocated. I dragged his face along the cobbles, I pushed my thumb into an eye. He sank his teeth into my wrist, and clawed my cheek bloody. And when at last he ceased to fight against my strangling grip, I dragged him to the sea-wall and threw his body down onto the rocks.

I stood panting, my fists still clenched. I glared toward the raiders, daring them to come, but the night was still, save for the waves and wind and the soft gargling of the woman as she died. Either the raiders had not heard, or they were too concerned with their own stealth to investigate sounds in the night. I waited in the wind for someone to care enough to come and kill me. Nothing stirred. An emptiness washed through me, supplanting my madness. So much death in one night, and so little significance save to me.

I left the other broken bodies on top of the crumbling sea-wall for the waves and the gulls to dispose of. I walked away from them. I had felt nothing from them when I killed them. No fear, no anger, no pain, not even despair. They had been things. And as I began my long walk back to Buckkeep, I finally felt nothing from within myself. Perhaps, I thought, Forging is a contagion and I have caught it now. I could not bring myself to care.

Little of that journey stands out in my mind now. I walked all the way, cold, tired and hungry. I encountered no more Forged ones, and the few other travellers I saw on that stretch of road were no more anxious than I to speak to a stranger. I thought only of getting back to Buckkeep. And Burrich. I reached Buckkeep two days into the Springfest celebration. The guards at the gate tried to stop me at first. I looked at them.

‘It’s the fitz,’ one gasped. ‘It was said you were dead.’

‘Shut up,’ barked the other. He was Gage, long known to me, and he said quickly, ‘Burrich’s been hurt. He’s up at the infirmary, boy.’

I nodded and walked past them.

In all my years at Buckkeep, I had never been to the infirmary. Burrich and no one else had always treated my childhood illnesses and mishaps. But I knew where it was. I walked unseeing through the knots and gatherings of merrymakers, and suddenly felt as if I were six years old and come to Buckkeep for the very first time. I had hung onto Burrich’s belt. All that long way from Moonseye, with his leg torn and bandaged. But not once had he put me on another’s horse, or entrusted my care to another. I pushed myself through the people with their bells and flowers and sweet cakes to reach the inner keep. Behind the barracks was a separate building of whitewashed stone. There was no one there, and I walked unchallenged through the antechamber and into the room beyond.

There were clean strewing-reeds on the floor, and the wide windows let in a flood of spring air and light, but the room still gave me a sense of confinement and illness. This was not a good place for Burrich to be. All the beds were empty, save one. No soldier kept to bed in Springfest days, save that they had to. Burrich lay, eyes closed, in a splash of sunlight on a narrow cot. I had never seen him so still. He had pushed his blankets aside and his chest was swathed in bandages. I went forward quietly and sat down on the floor beside his bed. He was very still, but I could feel him, and the bandages moved with his slow breathing. I took his hand.

‘Fitz,’ he said, without opening his eyes. He gripped my hand hard.

‘Yes.’

‘You’re back. You’re alive.’

‘I am. I came straight here, as fast as I could. Oh, Burrich, I feared you were dead.’

‘I thought you were dead. The others all came back days ago.’ He took a ragged breath. ‘Of course, the bastard left horses with all the others.’

‘No,’ I reminded him, not letting go of his hand. ‘I’m the bastard, remember?’

‘Sorry.’ He opened his eyes. The white of his left eye was mazed with blood. He tried to smile at me. I could see then that the swelling on the left side of his face was still subsiding. ‘So. We look a fine pair. You should poultice that cheek. It’s festering. Looks like an animal scratch.’

‘Forged ones,’ I began, and could not bear to explain more. I only said, softly, ‘He set me down north of Forge, Burrich.’

Anger spasmed his face. ‘He wouldn’t tell me. Nor anyone else. I even sent a man to Verity, to ask my prince to make him say what he had done with you. I got no answer back. I should kill him.’

‘Let it go,’ I said, and meant it. ‘I’m back and alive. I failed his test, but it didn’t kill me. And as you told me, there are other things in my life.’

Burrich shifted slightly in his bed. I could tell it didn’t ease him. ‘Well. He’ll be disappointed over that.’ He let out a shuddering breath. ‘I got jumped. Someone with a knife. I don’t know who.’

‘How bad?’

‘Not good, at my age. A young buck like you would probably just give a shake and go on. Still, he only got the blade into me once. But I fell, and struck my head. I was fair senseless for two days. And, Fitz. Your dog. A stupid, senseless thing, but he killed your dog.’

‘I know.’

‘He died quickly,’ Burrich said, as if to be a comfort.

I stiffened at the lie. ‘He died well,’ I corrected him. ‘And if he hadn’t, you’d have had that knife in you more than once.’

Burrich grew very still. ‘You were there, weren’t you,’ he said at last. It was not a question, and there was no mistaking his meaning.

‘Yes,’ I heard myself saying, simply.

‘You were there, with the dog that night, instead of trying for the Skill?’ His voice rose in outrage.

‘Burrich, it wasn’t like …’

He pulled his hand free of mine and turned as far away from me as he could. ‘Leave me.’

‘Burrich, it wasn’t Smithy. I just don’t have the Skill. So let me have what I do have, let me be what I am. I don’t use this in a bad way. Even without it, I’m good with animals. You’ve forced me to be. If I use it, I can …’

‘Stay out of my stables. And stay away from me.’ He rolled back to face me, and to my amazement, a single tear tracked his dark cheek. ‘You failed? No, Fitz. I failed. I was too soft-hearted to beat it out of you at the first sign of it. “Raise him well,” Chivalry said to me. His last command to me. And I failed him. And you. If you hadn’t meddled with the Wit, Fitz, you’d have been able to learn the Skill. Galen would have been able to teach you. No wonder he sent you to Forge.’ He paused. ‘Bastard or no, you could have been a fit son to Chivalry. But you threw it all away. For what? A dog. I know what a dog can be to a man, but you don’t throw your life over for a …’

‘Not just a dog,’ I cut in almost harshly. ‘Smithy. My friend. And it wasn’t only him. I gave up the wait and came back for you. Thinking you might need me. Smithy died days ago. I knew that. But I came back for you, thinking you might need me.’

He was silent so long I thought he wasn’t going to speak to me. ‘You needn’t have,’ he said quietly. ‘I take care of myself.’ And harsher, ‘You know that. I always have.’

‘And me,’ I admitted to him. ‘And you’ve always taken care of me.’

‘And small damn good that did either of us,’ he said slowly. ‘Look what I’ve let you become. Now you’re just … Go away. Just go away.’ He turned away from me again, and I felt something go out of the man.

I stood slowly. ‘I’ll make you a wash from helena leaves for your eye. I’ll bring it this afternoon.’

‘Bring me nothing. Do me no favours. Go your own way, and be whatever you will. I’m done with you.’ He spoke to the wall. In his voice was no mercy for either of us.

I glanced back as I left the infirmary. He had not moved, but even his back looked older, and smaller.

That was my return to Buckkeep. I was a different creature from the naïf who had left. Little fanfare was made over my not being dead as supposed. I made no opportunity for anyone to do so. From Burrich’s bed, I went straight to my room. I washed and changed my garments. I slept, but not well. For the rest of Springfest, I ate at night, alone in the kitchens. I penned one note to King Shrewd, suggesting that raiders might regularly be using the wells at Forge. He made no reply to me about it, and I was glad of it. I sought no contact with anyone.

With much pomp and ceremony, Galen presented his finished coterie to the King. One other besides myself had failed to return. It shames me now that I cannot recall his name, and if I ever knew what became of him, I have forgotten it. Like Galen, I suppose I dismissed him as insignificant.

Galen spoke to me only once the rest of that summer, and that was indirectly. We passed one another in the courtyard, not long after Springfest. He was walking and talking with Regal. As they passed me, he looked at me over Regal’s head and said sneeringly, ‘More lives than a cat.’

I stopped and stared at them until both were forced to look at me. I made Galen meet my eyes; then I smiled and nodded. I never confronted Galen about his attempt to send me to my death. He never appeared to see me after that; his eyes would slide past me, or he would exit a room when I entered it.

It seemed to me that I had lost everything when I lost Smithy. Or perhaps in my bitterness I set out to destroy what little was left to me. I sulked about the keep for weeks, cleverly insulting anyone foolish enough to speak to me. The Fool avoided me. Chade didn’t summon me. I saw Patience thrice. The first two times I went to answer her summons, I made only the barest efforts to be civil. The third time, bored by her chatter about rose cuttings, I simply stood up and left. She did not summon me again.

But there came a time when I felt I had to reach out to someone. Smithy had left a great gap in my life. And I had not expected that my exile from the stables would be as devastating as it was. Chance encounters with Burrich were incredibly awkward as we both learned painfully to pretend not to see each other.

I wanted, achingly, to go to Molly, to tell her everything that had befallen me, all that had happened to me since I first came to Buckkeep. I imagined in detail how we could sit on the beach while I talked, and that when I had finished, she would not judge me or try to offer advice, but would just take my hand and be still beside me. Finally, she would know everything, and I would not have to hide anything from her any more. I dared imagine no more beyond that. I longed desperately, and feared with the fear known only to a boy whose love is two years older than he is. If I took her all my woes, would she think me a hapless child and pity me? Would she hate me for all that I had never told her before? A dozen times that thought turned my feet away from Buckkeep Town.

But some two months later, when I did venture into town, my traitorous feet took me to the chandlery. I happened to have a basket with me, and a bottle of cherry wine in it, and four or five brambly little yellow roses, obtained at great loss of skin from the Women’s Garden where their fragrance overpowered even the thyme beds. I told myself I had no plan. I did not have to tell her everything about myself. I did not even have to see her. I could decide as I went along. But in the end all decisions had already been made, and they had nothing to do with me.

I arrived just in time to see Molly leaving with Jade. Their heads were close together, and she leaned toward him as they spoke in soft voices. Outside the door of the chandlery, he stooped to look into her face. She lifted her eyes to his. When the man reached a hesitant hand to gently touch her cheek, Molly was suddenly a woman, one I did not know. The two years’ age difference between us was a vast gulf I could never hope to bridge. I stepped around the corner before she could see me, and turned aside, my face down. They passed me as if I were a tree or a stone. Her head leaned on his shoulder, and they walked slowly. It took forever for them to be out of sight.

That night I got drunker than I had ever been, and awoke the next day in some bushes halfway up the keep road.

EIGHTEEN

Assassinations

Chade Fallstar, a personal adviser to King Shrewd, made an extensive study of Forging during the period just preceding the Red Ship wars. From his tablets, we have the following: ‘Netta, the daughter of the fisherman Gill and the farmer Ryda, was taken alive from her village Goodwater on the seventeenth day after Springfest. She was Forged by the Red Ship Raiders and returned to her village three days later. Her father was killed in the same raid, and her mother, having five younger children, was little able to deal with Netta. She was, at the time of her Forging, fourteen summers old. She came into my possession some six months after her Forging.

‘When first brought to me, she was dirty, ragged and greatly weakened owing to starvation and exposure. At my direction, she was washed, clothed and housed in chambers convenient to my own. I proceeded with her as I might have done with a wild animal. Each day I brought her food with my own hands, and stayed by her while she ate. I saw to it that her chambers were kept warm, her bedding clean, and that she was provided with the amenities a woman might expect; water for washing, brushes and combs, and all that is otherwise needful. In addition, I saw to it that she was furnished with sundry supplies for needlework, for I had discovered that prior to Forging, she had had a great fondness for doing such fancywork, and had created several artful pieces. My intention in all this was to see if, under gentle circumstances, a Forged one might not return to a semblance of the person she had formerly been.

‘Even a wild animal might have become a little tamer under these circumstances. But to all things Netta reacted with indifference. She had lost not only the habits of a woman, but even the good sense of an animal. She would eat to satiation, with her hands, and then let fall to the floor whatever was excess, to be trodden underfoot. She did not wash, nor care for herself in any way. Even most animals soil only one area of their dens, but Netta was like a mouse that lets her droppings fall everywhere, with no care for bedding.

‘She was able to speak, in a sensible way, if she chose to or wanted some item badly enough. When she spoke by her own choice, it was usually to accuse me of stealing from her, or to utter threats against me if I did not immediately give her some item she wanted. Her habitual attitude toward me was suspicious and hateful. She ignored my attempts at normal conversation, but by withholding food from her, I was able to elicit answers in exchange for food. She had clear memory of her family, but had no interest in what had become of them. Rather, she answered those questions as if answering questions about yesterday’s weather. Of her Forging time, she said only that they had been held in the belly of a ship, and that there had been little food and only enough water to go around. She had been fed nothing unusual that she recalled, nor had she been touched in any way that she remembered. Thus she could furnish to me no clue as to the mechanism of Forging itself. This was a great disappointment to me, for I had hoped that by learning how a thing was done, a man could discover how to undo it.

‘I endeavoured to bring human behaviour back to her by reasoning with her, but to no avail. She appeared to understand my words, but would not act on them. Even when given two loaves of bread, and warned that she must save one for the morrow or go hungry, she would let her second loaf fall to the floor, tread upon it, and on the morrow eat her own dropped leavings careless of what dirt clung to them. She evinced no interest in her needlework or in any other pastime, not even the bright toys of a child. If not eating or sleeping, she was content merely to sit or lie, her mind as idle as her body. Offered sweets or pastries, she would indulge until she vomited, and then eat more.

‘I treated her with sundry elixirs and herbal teas. I fasted her, I steamed her, I purged her body. Hot and cold dousings had no effect other than to make her angry. I caused her to sleep a full day and a night, to no change. I so charged her with elfbark that she could not sleep for two nights, but this only made her irritable. I spoiled her with kindnesses for a time, but as when I treated her with the harshest restrictions, it made no difference in how she regarded me. If hungry, she would make courtesies and smile pleasantly when commanded to, but as soon as food was furnished, all further commands and requests were ignored.

‘She was viciously jealous of territory and possessions. More than once she attempted to attack me, for no more reason than that I had ventured too close to food she was eating, and once because she suddenly decided she wished to have a ring I was wearing. She regularly killed the mice her untidiness attracted, snatching them up with amazing swiftness and dashing them against the wall. A cat that once ventured into her chambers met with a similar fate.

‘She seemed to have little sense of the time that had passed since her Forging. She could give good account of her earlier life, if commanded when hungry, but of the days since her Forging, all was as one long “yesterday” to her.

‘From Netta, I could not learn if something had been added to her or taken away to Forge her. I did not know if it was a thing consumed or smelled or heard or seen. I did not know if it was even the work of a man’s hand and art, or the work of a sea-demon such as some Farlanders claim to have power upon. From a long and weary experiment, I learned nothing.

‘To Netta I gave a triple sleeping-draught one evening with her water. I had her body bathed, her hair groomed, and sent her back to her village to be decently buried. At least one family could put finis to a tale of Forging. Most others must wonder, for months and years, what has become of the one they once held dear. Most are better off not knowing.’

There were, at that time, over one thousand souls known to have been Forged.

Burrich had meant what he said. He had nothing more to do with me. I was no longer welcome down at the stables and kennels. Cob especially took savage pleasure in this. Although he was often gone with Regal, when he was about the stables he would often step to block my entry. ‘Allow me to bring you your horse, Master,’ he would say obsequiously. ‘The stablemaster prefers that grooms handle animals within the stables.’ And so I must stand, like some incompetent lordling, while Sooty was saddled and brought for me. Cob himself mucked out her stall, brought her feed and groomed her, and it ate at me like acid to see how quickly she welcomed him back. She was only a horse, I told myself, and not to be blamed. But it was one more abandonment.

I had too much time, suddenly. Mornings had always been spent working for Burrich. Now they were mine. Hod was busy training green men for defence. I was welcome to drill with them, but it was all lessons I had learned long ago. Fedwren was gone for the summer, as he was every summer. I could not think of a way to apologize to Patience, and I did not even think about Molly. Even my forays to the taverns in Buckkeep had become solitary ones. Kerry had apprenticed to a puppeteer, and Dirk gone for a sailor. I was idle and alone.

It was a summer of misery, and not just for me. While I was lonely and bitter and out-growing all my clothes, while I snapped and snarled at any foolish enough to speak to me, and drank myself insensible several times a week, I was still aware of how the Six Duchies were racked. The Red Ship Raiders, bolder than ever before, harried our coastline. This summer, in addition to threats, they finally began to make demands. Grain, cattle, the right to take whatever they wished from our seaports, the right to beach their boats and live off our lands and people for the summer, their choice of our folk for slaves … each demand was more intolerable than the last, and the only things more intolerable than the demands were the Forgings that followed each refusal by the King.

Common folk were abandoning the seaport and waterfront towns. One could not blame them, but it left our coastline even more vulnerable. More soldiers were hired, and more, and so the levies were raised to pay them, and folk grumbled under the burden of the taxes and their fear of the Red Ship Raiders. Even stranger were the Outislanders who came to our shore in their family ships, their raiding vessels left behind, to beg asylum of our people, and to tell wild tales of chaos and tyranny in the Out Islands where the Red Ships now ruled completely. They were a mixed blessing, perhaps. They were cheaply hired as soldiers, though few really trusted them. But at least their tales of the Out Islands under Red Ship domination were harrowing enough to keep anyone from thinking of giving in to the Raiders’ demands.

About a month after my return, Chade opened his door to me. I was sullen over his neglect of me, and went more slowly up his stairs than ever I had before. But when I got there, he looked up from crushing seeds with a pestle with a face full of weariness. ‘I am glad to see you,’ he said, with nothing of gladness in his voice.

‘That’s why you were so swift to welcome me back,’ I observed sourly.

He stopped his grinding. ‘I’m sorry. I thought perhaps you would need time alone, to recover yourself.’ He looked back to his seeds. ‘It has not been an easy winter and spring for me, either. Shall we try to put the time behind us, and go on?’

It was a gentle, reasonable suggestion. I knew it was wise.

‘Have I any choice?’ I asked sarcastically.

Chade finished grinding his seed. He scraped it into a finely-woven sieve and put it over a cup to drip. ‘No,’ he said at last, as if he had considered it well. ‘No, you haven’t, and neither have I. In many things, we have no choice.’ He looked at me, his eyes running up and down me, and then poked at his seed again. ‘You,’ he said, ‘will stop drinking anything but water or tea for the rest of the summer. Your sweat stinks of wine. And for one so young, your muscles are lax. A winter of Galen’s meditations has done your body no good at all. See that you exercise it. Take it upon yourself, as of today, to climb to Verity’s tower four times a day. You will take him food, and the teas I will show you how to prepare. You will never show him a sullen face, but will always be cheerful and friendly. Perhaps a while of waiting on Verity will convince you that I have had reasons for my attention not being centred on you. That is what you will do each day you are at Buckkeep. There will be some days when you will be fulfilling other assignments for me.’

It had not taken many words from Chade to awaken shame in myself. My perception of my life crashed from high tragedy to juvenile self-pity in a matter of moments. ‘I have been idle,’ I admitted.

‘You have been stupid,’ Chade agreed. ‘You had a month in which to take charge of your own life. You behaved like … a spoiled brat. I have no wonder that Burrich is disgusted with you.’