Полная версия

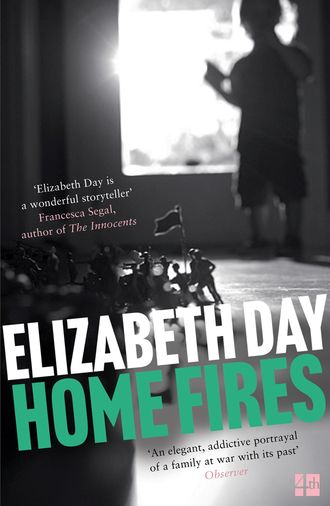

Home Fires

Caroline does not acknowledge him, but shifts away to one side, releasing her arm from Andrew’s grasp. She sits perfectly still and Andrew is left feeling that he has done something wrong, that he is being reproached by her, silently. But then, when they stand to sing the next hymn, she turns and smiles at him and mouths ‘Thank you’ and the natural equilibrium between them is restored. He puts his arm round her waist, lightly, to let her know he loves her.

But the organist is thumping out the notes too loudly and a headache that has been plaguing him since morning thuds insistently back into life, pricking the tightness behind his eyes, so that by the time the small congregation emerges, blinking, into the midday light, Andrew feels untethered from the ground, as though he is viewing proceedings through a pool of shallow water, his ears muffled so that everyone’s speech sounds disjointed and slow.

He removes his sunglasses from his jacket pocket and slips them on. The crispness of the autumnal daylight is immediately softened by an overlay of sepia. He looks around and sees Caroline, standing underneath the spreading branches of a sycamore tree just in front of a cluster of faded and slanting gravestones. She is laughing, relieved to have her son back in her arms, able now to joke about the timing of his tears.

‘Typical,’ he hears her saying to the vicar. ‘He’s been good as gold all morning and then just at the moment . . .’

Good as gold, thinks Andrew. She never used to speak like that. It amuses him, this habit she has of picking up phrases like a magpie picks up glitter. She tries so hard to be someone else, something better and yet Andrew loves her exactly as she is. It doesn’t matter how much he tells her this. She has no faith in herself, he thinks as he walks towards her. No faith at all. ‘Happens all the time,’ the vicar is chuckling amiably. ‘I seem to have that effect on babies.’ His mother is standing next to the vicar in a smartly tailored two-piece suit in royal blue. She laughs, causing the feathers on her fascinator to tremble. ‘Our son was just the same,’ Elsa says. ‘You should have heard the fuss that Andrew made. Of course, he’s been compensating ever since by being so terribly sensible.’

Caroline giggles, arching her eyebrows to show she knows exactly what her mother-in-law means, that she gets the joke.

Andrew edges into the circle of conversation, giving a non-committal smile. He holds out his arms to take Max, overtaken by the need to hold him, to feel him close.

‘Are you all right?’ Caroline asks and he sees that instead of giving him the child, she has moved to one side so that Max’s face is obscured by the folds of her blouse, the silhouette of her hip.

‘Fine, fine,’ he says, putting his hands back into his pockets. ‘Just a bit of a headache.’

Elsa looks at him. Her face, still beautiful through the wrinkles, is impeccably made up: blended brushstrokes of crimson lipstick, brown-black mascara, grey eyeshadow at the corners of her lids, lighter brown on the inside. She smells lightly of tuberose. ‘Have you taken anything for it?’

He nods. Elsa pats him on the arm. ‘Some champagne will do you good,’ she says. ‘When we get back, you’ll sit down and I’ll bring you an ice-cold glass of fizz.’

He sees Caroline frowning and then he remembers: they haven’t bought any champagne. Caroline had thought sherry would be more ‘appropriate’.

‘But first, I insist on having a cuddle with my glorious grandson,’ Elsa is saying, moving towards Caroline with elegant arms outstretched, a discreet gold bracelet hanging from her left wrist. ‘Oh I could just eat him alive.’

The vicar gives a giant guffaw, arching his back so that his stomach protrudes over his waistband. ‘Grandparents have the best of both worlds, don’t they?’ he says. ‘They can always give the little blighters back at the end of the day!’

The vicar carries on talking, but Andrew is not listening. He is looking, instead, at the interaction between his mother and his wife. Elsa still has her arms outstretched, is still waiting for her grandson to be handed over. Perhaps it is the headache that makes it seem such an interminable wait, as though the ticking of time has slowed down until it is more pause than motion. But it seems to him as though Elsa waits for several long minutes, her arms gradually sagging and falling back down to her sides when she finally realises Caroline is not going to pass the baby over.

And in this new, slowed-down world his head is inhabiting, Andrew is able to see each minute sliver of reaction in perfect detail. He sees his wife give an almost inconspicuous shake of the head. He sees her smile become rubbery and false. And then he sees her tighten her grip around Max’s gown, lifting up the palm of one hand to his downy head, as though shielding him.

He sees Elsa, for the briefest of moments, look as if she has been slapped. And then, almost immediately, she masks her face with a blank politeness.

He is astonished by the clarity with which he notices all of this. When his thoughts click back into normal time, nothing appears to have happened. The vicar is still talking. Caroline is laughing easily again, saying apologetically, ‘I’m sorry, Elsa, I think he needs changing. I’ll just take him inside’ and then Elsa is tucking a strand of hair behind her ear, giving a meticulously understanding smile.

‘I’ll do it,’ Andrew says and he understands, as he is offering, that this is a test, that he is wondering how Caroline will react.

‘Don’t be silly, darling,’ she says. She walks off towards the vestry with Max squirming in her arms. ‘You know you can’t change nappies for toffee.’

For toffee. Another phrase that doesn’t fit.

He looks at her go, he hears the brisk clicking of her heels against the flagstones, the sway of her skirt as she moves.

He puts his sunglasses back in his jacket pocket and takes Elsa’s arm. ‘Come on, Mummy,’ he says. ‘Let’s make a start on wetting the baby’s head.’

She looks up at him, warmly.

‘Good idea.’

They say goodbye to the vicar and walk towards the car, where they sit in a charged kind of silence until Caroline comes back. He notices as she approaches the passenger window that her face is unreadable: a freshly polished piece of silver.

‘All done,’ she says, as she straps Max into the baby seat, giving him a small kiss on his brow before getting into the car.

The hem of Caroline’s dress catches in the door when she closes it. ‘Hang on,’ she says, opening the door and retrieving the dress, now stained with a smear of grease. ‘What a nuisance,’ Caroline says, tutting to herself. She clicks her seatbelt into place, then twists round to look at Andrew and gives his hand a squeeze.

‘No one will see it,’ he says automatically. ‘Don’t worry.’

‘You’re right. It’s not as if anyone will be looking at me, will they?’

‘No,’ he replies, turning the key in the ignition. ‘It’s all about Max from now on.’

As if on cue, Max gives a grizzly little whimper from the back seat. They all laugh, lightly.

Andrew releases the handbrake and the car judders forward. Behind them, the church recedes, its steeple gradually disappearing behind the rising bend in the road.

Part II

Caroline

For Caroline, it had all started with a knock on the door.

Ta-tat.

A quaver, then a crotchet, thumped out against the wood.

She thinks now how odd it was that they knocked when there was a perfectly good doorbell, a square box nailed to the wall with a circle-white buzzer so that every time she passed it she thought of an unfinished domino tile. Andrew had installed it several years previously, disproportionately proud of his prowess with the Black & Decker drill she had given him for Christmas. At first, he put it too high up on the doorframe so that no person of average height would be able to reach it. Then he moved it down several inches, but the wood remained dotted with holes where the doorbell had once been.

So the point was: they must have seen the doorbell and chosen to ignore it. Perhaps, she thinks, it was protocol, an anachronistic gesture of respect from a time before the installation of domestic electronics.

Whatever the reason, it was a knock that signalled Caroline’s life was about to change. The knock seemed to echo more loudly than a buzzer, its staccato force reverberating clean and clear against the hallway tiles. It bounced off the buttermilk-painted walls, pinging its way like a pinball up to the top of the stairs where she was sitting cross-legged on the carpet in her jeans, folding freshly washed pillowcases to stack on a shelf in the airing cupboard.

She called to Andrew to answer. It was a Saturday and they had been out for the afternoon, shopping for things they believed they needed but probably could have done perfectly well without: cushions for the conservatory chairs, a new fig and bergamot scented candle for the living room, a long-handled spoon for jars of marmalade to replace one that had mysteriously disappeared. On the way back to the house, they had stopped for tea at the vegetarian café and shared a slice of carrot cake, the vanilla cream icing melting sweetly in their mouths.

There was no answer from Andrew and Caroline remembers being irritated by that. She remembers flinging down the pillowcase she had been folding and making her way hurriedly downstairs, cursing her husband’s absent-mindedness under her breath.

It seems so trivial now to have got upset over such a tiny inconvenience – magical, almost, to think that her life could have been so content back then that she had to invent reasons to be upset simply to give her day a bit of texture.

There was another knock before she got to the bottom of the stairs: three beats in quick succession.

Was it then that she began to sense that things were not as they should be? Was it then that she felt the first thump of blood to her head? She isn’t sure. There is a temptation, in retrospect, to claim some psychic maternal intuition that all was not right. But she doesn’t think she suspected anything. It had been a very normal Saturday up until that point. She does remember walking briskly across the hallway so that she wouldn’t keep whoever it was waiting.

She was still, at that time, mindful of the necessary social politesse.

She walked down the hallway and looked through the glass-panelled front door to see a warped beige-blue darkness, an indistinct, lumpy shape that gradually shifted apart into two inky shadows. One of the shapes appeared to have yellow stripes on one shoulder but when it moved, the yellow dispersed, swirling into flakes of confetti with each dent of the glass. She squinted, unsure of what she was seeing and yet aware that it was somehow an echo of a thing she recognised.

Something about the way they were standing, erect, unbowed, certain, made the pieces fall into place. In her mind, the jumbled sparkle of a hundred kaleidoscope fragments slid into sudden formation.

Two men.

Uniforms.

A knock on the door.

This is what happens when soldiers die.

She felt a hole in the base of her stomach, as though something had unclenched within her and yet she kept moving towards the door. She turned the handle and opened it several inches but then she stopped, not trusting herself any further. Her eyes were shut, as if she were a child who could make something disappear by not seeing it.

‘Is this 25 Lytton Terrace?’ said the first man. ‘Are you Mrs Weston?’ He was dressed in charcoal grey and wore a gold signet ring on his little finger polished to an iridescent brightness. She didn’t notice his colleague until much later.

Time slowed. The seconds dripped like treacle from a spoon.

‘Would we be able to come inside?’ the first man asked. And she knew, then. She knew.

She bent over before he could say any more, clutching at her waist, head dropping down so that she did not have to look at them. For a few seconds, she could make no noise. It felt as though the next breath would not come but remain, halted, just beyond her reach. She moaned. She said ‘No,’ and her voice when she heard it sounded far away: a whisper on the opposite side of an echoing cave.

She slammed the door shut. She leaned against it with her whole weight, pushing the glass with her hands, fingers splayed against the light. She pushed so hard that her flesh turned white and numb. And all the time she was saying no, no, no, feeling the lurch of desperate nausea in the pit of her stomach, the sweat breaking out underneath her arms and trickling down her spine. She was shaking her head, refuting the thought that this could possibly be real. It was not true. It couldn’t be.

The two men knocked on the door again, saying her name, trying to be kind, but she couldn’t let them in. She would not let them into the house. She would not listen to what they had to say. She thought to herself that if she could stop them from speaking, if she could keep the door shut, if she could prevent them crossing the threshold, then everything would stay the same. She would prise open a gap in time, a velvety corner she could squeeze into where she would be safe, cocooned.

She heard footsteps running up behind her and for a moment she thought that the men had somehow got inside the house and were coming to get her, but then she remembered Andrew. Her husband.

She remembered with a rush that he existed, that he was with her, that she was not alone, that there was a rational shape to things, and then she felt his hands around her wrists, his warm, reassuring palms firmly gripping her throbbing veins. He was murmuring, saying something to her that made no sense, but his voice was familiar and soothing and the tendons in her hands relaxed as he prised them off the glass and held them tightly in his. She looked at his mouth and it was moving and he was making a sound but it took several seconds until Caroline could understand anything.

‘We have to let them in,’ he was saying. ‘We have to let them in.’ And his face was colourless and scared and she was shaking her head, but he simply kept repeating the same phrase over and over and she was lulled by the weird rhythm of his voice and then she felt exhaustion come over her and she slumped against him while he opened the door and let the two men in dark suits across the threshold.

And that is how she learned that her darling son was dead.

Later, the two men tried to tell her how Max had died but all Caroline could hear was a vague blur of voices. She had the overwhelming sensation of being too cold and then she went limp in Andrew’s arms, as if she no longer possessed enough energy to expend on even the most basic of tasks. He half-carried her to an armchair in the sitting room, upholstered in a flowered pale-green fabric and she turned her head and pressed her face into the back of it so that she would not have to look at anyone.

She breathed in the armchair’s comforting scent of hair and familiar sweat and felt the roughness of the material against her skin. She stared at a sun-faded lily stitched into the fabric, noticing the curl of the petals and the worn-away threads of the stalk. She did not cry but according to Andrew, she was whimpering – that was his word, ‘whimpering’ – like a broken-down dog limping to the side of a road.

Andrew managed to ask the relevant questions, to elicit the desired information, his voice flat and devoid of emotion, his hands placed carefully over the curve of each knee-bone. The two men said that Max had been on foot patrol in Upper Nile State, scanning the African countryside for pockets of resistance and ensuring the safety of the local villagers, when he stepped on a landmine. For some reason, they didn’t call it a landmine. They referred to it as an Improvised Explosive Device, or IED. An acronym. It seemed wrong, somehow, to reduce his death to three slight letters.

The landmine had exploded directly underneath Max’s feet. He was thrown backwards several metres, landing on his back and snapping his vertebrae. A two-inch piece of shrapnel sliced his chest in half. It lodged itself so close to his heart that the army doctor who got to him some time later could not risk extracting the metallic fragment in case it increased the bleeding. The doctor did what he could to staunch the flow of blood, pressing down with his own hands when they had run out of balled-up T-shirts and improvised bandages.

There would, she imagines, have been a few seconds when it could have gone either way: that fragmented moment that lies between the everyday and the nightmare. And then, in a faraway country, lying in a pool of his own blood, he stopped breathing. And that was it for Lance Corporal Max Weston, aged 21. That was it.

When the men had finished speaking, Andrew offered them a cup of tea. They said no, and she was relieved by that; relieved that they did not have to pretend or act normally.

Caroline had questions. So many questions.

What was Max’s last thought?

Do you have last thoughts when you are dying?

Would his life have flashed through his mind as one is told it does, or would there not have been enough time?

What would his face have looked like?

Was his skull still intact, the smooth dip into the nape of his neck that she loved so much?

Was he always meant to die at 21? Was the shadow of his death hanging over them all during those times they had together? Had they simply been too arrogant or too innocent not to pay attention to it?

Did he think of his mother at all?

Did he know how much she would miss him?

Did he know that he was her life, her everything?

And: without him, how could she go on?

In the days that followed, Caroline would spend hours sitting in the kitchen, a mug of cooling coffee cradled in her hand, thinking back to the time when Max was a child, searching for any clues she might have missed about the path his life took.

But the irony of it was that Max had never played with soldiers when he was little. Andrew had once given him a much-cherished set of tin figurines, inherited from his own father, in the hope that Max would carry on the Weston family tradition of reconstructing interminable historic battles on the bedroom carpet. When Max opened the musty cardboard box and inspected the soldiers’ minute Napoleonic uniforms greying with age, their bayonets blunted by the repeated pressure of other children’s excitable fingers, he was distinctly unimpressed. He was nine years old – the perfect age, one would have thought, for playing with action men.

‘You see, this chap here,’ Andrew said, lifting up a portly-looking gentleman on horseback, ‘is in charge of the cavalry.’ And he passed the toy to Max, who looked pensively at his father before taking it wordlessly in his hand.

‘Why is he on a horse?’

‘That’s how soldiers used to fight. In the old days. It meant they could move faster and cover more ground.’

Andrew looked up at Caroline and caught her eye and she could see he was delighted by Max’s tentative curiosity. He up-ended the box and the soldiers tumbled out in a metallic heap. Max looked on warily, the cavalryman still clasped in his hand. He was an extremely thoughtful child, in the original sense of the word: he would examine everything with great care before deciding what to do about it. Unlike most boys of his age, he was not given to spontaneous outbursts of random energy or unexplained exuberance. Rather, he would step back and evaluate what was going on and then, if it was something that interested him, he would join in with total commitment.

He was selective about the people and hobbies he chose to pursue but Max’s loyalty, once won, was never lost. From a very young age, he pursued his enthusiasms with utter dedication. After a school project on the history of flight, he spent hours making model aircrafts and would put each new design through a rigorous set of time trials in the hallway, recording the results neatly in a spiral-bound notebook. When he discovered a talent for tennis, he practised religiously, hitting a ball against the back wall of the garage until the daylight faded. He met his best friend Adam on the first day of primary school and although they did not immediately take to each other, they became close through a shared love of Top Trumps and were then inseparable, all the way to the end.

But in spite of Andrew’s early optimism, he never could get Max to play with those tin soldiers. For weeks, they remained in a haphazard heap on the floor – the cavalryman standing disconsolately on his own by the skirting board looking on with despair at the unregimented jumble of his men – until Caroline cleared the toy army away, putting them all back in the box which stayed, untouched, underneath the bed in Max’s room for years. In the days after his death, she took to going up to his room and sliding the box out. She liked to find the cavalryman and to hold him in her hand and to think that her son had also held him like this. It made her feel that she could touch Max again in some way, as if a particle of his skin might still have been lingering on the silvery-cool surface and they could make contact, even through the tangled awfulness of all that had happened. She sat for hours like that, feeling the time ebb gently away.

Perhaps Max was a gentle child partly because he did not have to compete for their attentions with other siblings. It had taken them years to conceive and then, just at the point where it had seemed to be hopeless, Max had made his presence known. The first time Caroline heard him cry after he was born, she instantly recognised it as the sound of her child. You could have put Max in an auditorium full of wailing babies and she would have known. Andrew made fun of her for that, but he couldn’t have understood. He wasn’t there at the birth – men in those days weren’t – and she felt afterwards that he had missed out. Deep down, there was still a part of her that felt Andrew was never as close to their son as she was. And now, as she sat in the kitchen chair, the lingering acridity of coffee in her mouth, she genuinely didn’t believe his grief could be as profound as her own.

The military was the last career either of them had imagined for Max. He grew into a popular, self-assured teenager, the kind of boy that seems to radiate light. He was good at everything: academically gifted, a brilliant sportsman and yet he retained an artistic temperament, a kindness around the edges that set him apart from his contemporaries. His friends all said so at the funeral.

He was made head boy even though he attended the local boarding school as a day-pupil and it was practically unheard of for a non-boarder to be asked. They were talking about Oxbridge, wondering whether to put him up for a scholarship, and then, without warning, Max announced over dinner one evening that he wasn’t going to university.

‘What do you mean you’re not going to university?’ said Andrew, his knife and fork hanging in mid-air.

Max laughed. He had this infuriating habit of defusing tension with laughter – it always worked because it made it quite impossible to be angry with him.

‘I mean just that, Dad. I’m not going. I don’t think it’s right for me.’

Caroline looked at her son and saw that, despite the twitch of a smile, he was totally serious. She saw, all at once, that he would not be dissuaded. She had always imagined Max would be a barrister or an academic, someone who wore his success lightly and yet who was all the more impressive for it; someone who was impassioned by what he did and yet not defined by it. She could see herself talking about him to her friends in that murmuring, boastful way that proud mothers have, dropping nonchalant mentions of his latest achievement into conversation. She had wanted everything for her son, for him to achieve all the things she was never able to.

But his announcement shattered that illusion in a matter of seconds. Caroline forced herself to adopt a lightness of tone.