Полная версия

Lust

Lust or

No Harm Done

Geoff Ryman

Dedication

para o meu Txay

Um livro dedicado a ti deveria ser intitulado Amor, ou no mínimo: Sem Escândalo. Eu prometi que nele tu não te encontrarias, mas tu estás em todo lugar.

Epigraph

‘In the bend God created the hen and the education. And the education was without founder, and void; and death was upon the falsehood of the demand. And the sport of God moved upon the falsehood of the wealth. And God said, Let there be limit; and there was limit.’

A text produced from the Book of Genesis using a method invented by Jean Lescure in which each noun is replaced with the seventh noun following it in a dictionary.

As reported in Oulipo Compendium edited by Harry Matthews and Alastair Brotchie

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Part I

So how does it start?

Who indeed is Michael?

So where is Philip?

Was the guard hit?

Can I call up a copy of someone else?

What if this isn’t about sex?

Can Angels be dead?

Can I make them do it when I’m not there?

Do they have to be male? Can I make more than one at once? Where do they go back to?

Who killed Dumb Duck?

Do people I copy really know it?

Can Angels do work?

Can they give me Aids?

Can I cure Angels who are sick?

Part II

What’s so painful about love?

Why don’t you just try joy?

Does Viagra work?

If you could sleep with anyone in the world, who would it be?

The men I slept with, did they make a difference?

Why are men satisfied with whores?

Do blondes have more fun?

Who’s for real?

What’s eating Michael Blasco?

So what do you want, Michael?

You are a person?

What am I looking for?

Why does God suffer the Devil?

Did we learn anything?

Part III

What do you want for Christmas?

What do I do next?

Acknowledgement

About the Author

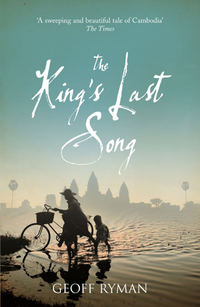

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

So how does it start?

Michael was happy. It was the first day of his research project. His team waited for him outside the gates of the lab, in the March chill. Ebru, Emilio and Hugh all smiled when they saw him.

It was a new lab, in rooms within arches under a railway. Michael had the keys, leading his team into one beautiful new room after another. They moved their desks and wired up their computers. They arranged staplers, pens and envelopes in drawers, determined that everything would stay tidy.

Ebru had brought flowers and a traditional Turkish shepherd’s cloak to hang on the wall. She was one of Michael’s students, doing a doctorate of her own, and had been hired to help administer the project. Ebru had bet Emilio a bottle of champagne that his new network would crash. Instead, the network came triumphantly to life, and they exchanged chiding e-mails, and raised glasses of champagne to the start of their brave new project.

‘To continued funding,’ toasted Michael. They all laughed.

The first shipment of eggs arrived in a box marked FRAGILE COMPUTERS. This was to fox the animal rights activists. The eggs were packed in grey foam like recording equipment. Ebru and Michael laid them out in the darkroom, on straw, to hatch. Everything was in place.

‘This is going to work,’ said Michael.

In the evening Michael went to his gym. He saw Tony. Tony was a trainer and Michael had a crush on him. Tony was tall and sleek and so innocent in his manner that Michael’s nickname for him was the Cherub. Tony had a radiant announcement to make.

‘I decided to take the plunge,’ Tony said. ‘Jacqui and I are going to get married.’ He had the eyes of a happy schoolboy.

‘Aw, that’s fantastic. Well done!’ said Michael and they did an old-fashioned hand slap. Tony’s hair was cut short and dressed in spikes. Everything about him took Michael back to his youth. Tony talked a little bit about how he had realized he didn’t want anyone else. ‘It’ll mean moving up north, but hey, she’s worth it.’

That’s what I want, thought Michael. I want a beautiful love.

Inspired in his heart and in his belly, Michael decided to visit the sauna in Alaska Street.

The smell of the place – hot pinewood, steam and bodies – produced an undertow of excitement as if something were pulling insistently downwards on his stomach. Naked men circulated in the steam in early evening.

Stripped of his glasses and lab coat, Michael was tall and athletic. A young Sikh with his hair tied at the top of his head in a bun saw Michael and did an almost comic double take. He was hairy and running slightly to fat, but the face, Michael suddenly saw, was smooth as marble. This was a young man with a fatherly body.

Michael followed the Sikh into the steam room with its benches. The Sikh looked at him with a teasing smile. They moved towards each other.

Michael didn’t trust kissing. He knew people often brushed their teeth before cruising. Brushing teeth always produced blood; blood carried the virus. When the boy leaned towards him, Michael turned his head away and pressed his cheek against his. Michael gave him quick, dishonest pecks on the lips, pretending to be romantic and playful instead of merely safe.

Even this was enough for the young man. They sat down and Michael leaned back on the bench as they embraced. Briefly they made a shape together like a poster for Gone with the Wind. Then the Sikh slipped lower and went to work (work was the only word for it) on Michael’s cock.

Michael’s cock stayed dead. All the young man’s ministrations only made it worse. It retreated further, back up and away. Not again, thought Michael, not again. It always happened, and it was always worse than Michael remembered. It was always worse with someone he liked. Most especially it happened with people he liked. The Sikh stopped, and looked up. He turned down his mouth in a show of childish disappointment.

Michael asked, ‘Are you too hot? Would you like something to drink?’

It was a way of saving face.

On the mezzanine, there were free drinks in the fridge and smelly beanbags on the floor. Michael poured them each a glass of spring water. Perched on a beanbag like a Buddha, the boy shook down his long glossy hair and began to retie it. Michael wanted to take him home and watch him wind it in his turban.

Michael passed him the water and the young man gave him a sharp little smile of thanks. When Michael lay down next to him, the Sikh stayed seated upright. In his heart, Michael knew what that meant, but yearning and hope persisted.

The young man talked politely. He was a medical doctor, a specialist in tropical diseases. He had been working in Africa and was back home to see his family. His name was Deep.

Michael asked him: did he work for Médecins sans Frontières?

‘No, I don’t like those organizations. They are too Western. They go there thinking they will show the natives how to do it. But, you know, they have no experience of infectious disease. I apply for the same jobs as the local doctors. I learn more that way.’

He was pleased to talk about his time there. The lack of roads, the digging of wells. Suddenly Deep lay back and let Michael rest his head on his fatherly bosom. Deep’s breath smelled of liquorice. ‘You know, I was working in a hospital in Malawi, by a lake. I was sitting out by myself drinking a beer. And I could see the animals come down to drink. The deer and the lions. And I could watch the deer as they kept watch. They kept flicking their ears. There was a moon on the lake.’

I’d go there with you, thought Michael. For just a moment he glimpsed another life. He was by that lake with Deep and they were together and Michael was doing … what? Michael was binding an antelope’s broken shin.

Michael ventured forth. ‘I, uh, have a boyfriend, but he won’t be there now. I don’t live very far from here.’

Despite his size, Dr Deep’s face was thin, slightly cynical, and it did not respond to the suggestion.

Michael endeavoured. ‘Would you like to come back with me?’

Dr Deep shook his head. ‘I’m not what you’re looking for.’

Oh, oh, but you are, thought Michael. ‘You’re sure?’ he asked and tried to engineer a winning smile.

Dr Deep was sure. ‘You know, I have been very tired and tense coming back here to see my family. I’m about to change countries again. So I just came here for the sex.’

They kissed and parted company. Deep was one of those perennial boys who only like older men. Over the next 45 minutes Michael watched Dr Deep kneel in front of one middle-aged man after another, his head bobbing away and then abruptly withdrawing, like a bee gathering honey. A medically trained bee who must know the risks.

The last Michael saw of Dr Deep, he was standing utterly alone, having sucked off every older man who wanted sucking. Dr Deep held up his towel, masturbating on show. Only one person was watching, but Dr Deep was looking pointedly away from Michael.

It’s all you want, Michael thought in disappointment. And if I’d been able to give you that, would you have talked to me? Gone out to a movie with me? Become friends? Do you want to die that badly, that you can’t even take time to talk? No one ever even talks. No one ever rings back. Is a hard dick really that important to you faggots?

How could I be stupid enough to get emotional? I know the score; I can’t get it up, so I either put up or dry up. I know what will happen, it always happens and I always forget. I always keep thinking it’s not that bad. But it is that bad. It’s like I think it will clear up by itself if I leave it alone. Like a sock that loses its other half. You put it back in the drawer, hoping it’ll find the other half by itself.

Well, I’m sorry. I’m sorry that I look like such a big butch man who’ll slap you and then fuck you silly. I’m sorry that I got a bit romantic. I won’t do it again. I keep forgetting what you guys are like.

Michael dragged his ass back into his underwear and out to Waterloo station, and on the underground platform. He cursed sex. He cursed the need for it, and how men wanted it. He cursed being gay. He cursed all other gay men. He cursed his dick and he cursed himself. As all the day’s happiness crushed around him like ruins in an aftershock, he prayed, or came as close to praying as he could get.

Michael pleaded for all the weary dead weight of his sexual desire to be taken from him. ‘Look, just castrate me, get rid of it, please, please just take it all away!’

Was a train coming? Wind blew along the platform; a newspaper rose up by itself into the air.

And Michael noticed that his gym instructor was standing a few feet away. Oh Jesus, not now, thought Michael. He didn’t want to see happiness; he didn’t want to see joy. He looked at Tony and thought: all I want to do is see your dick.

There on the platform, with fifteen other people, Tony pulled down first his tracksuit bottoms and then his clean white briefs. The Cherub stood still and exposed, his bovine thighs and brown pubic hair on display. His stare was as blank and disconnected as a sleepwalker’s.

The people on the platform looked disconnected as well. A greying man in a tan checked jacket glanced sideways and began to edge closer, eyes flickering. A woman searched her purse with immense concentration.

Then Tony sat down on the platform, and rolled onto his back, sticking the perfect bottom into the air, like an animal about to be spayed.

Oh, Jesus, thought Michael. So much for innocence. Bitterness and rage were countered by another thought: Tony must be in trouble.

Michael walked towards him. He saw the chords of muscle on the inside leg, and the head of the reasonably sized uncircumcised cock. Michael looked and then was sorry for looking. Tony gazed up at him, eyes unfocussed, dim with a half-formed question.

‘Fancy a portion?’ the Cherub asked.

Drugs, Michael decided. He doesn’t normally do drugs, so he’s gone and got what he thought was E only it was speed, plaster of Paris and battery acid.

‘Tony. What are you doing on the ground?’ Michael felt the eyes of the other people on the platform. His ears burned. He wanted them to know his intentions were honourable. The Cherub blinked, his head haloed by the grey and white patterns of the platform paving.

‘Stand up, come on.’

Michael didn’t want to touch him in public. Tony rolled to his feet. He stood without adjusting his clothes, facing the woman with the handbag. She looked like she might pull it down over her head.

Pull your trousers up! thought Michael, and immediately, the Cherub bent down and nipped both layers of clothing back into place.

‘Did you take anything? Do you remember what it was?’

The mouth hung open, the lips fatter when they were not smiling. Tony’s brows clenched, trying to find an answer. ‘I didn’t take anything.’

‘Are you sure? Try to think. What was it called?’

Tony nodded his head solemnly, yes. ‘Diclofenac,’ he said. ‘For my knee.’

Michael was a biologist. Diclofenac was a powerful anti-inflammation drug. Did it have side effects?

‘Have you taken it before?’

Tony nodded yes again, like a child.

The wind blew. Like a friend showing up, the train rumbled out of the tunnel. ‘This is my train,’ said Michael, trying to keep the tone conversational. ‘Where are you going, Tony?’

The Cherub replied as if the answer were obvious. ‘With you.’

It wouldn’t be right to leave him. Michael looked up at the handbag lady and she looked away hastily. The greying man looked miffed that Michael had got there first. Michael pushed his way onto the train as others were getting off, and Tony followed him. Michael clenched the handrail almost as hard as he was clenching his teeth, and looked around him.

Two teenage Indian boys were talking about cars or computers in a jargon he didn’t understand. A woman turned over a page of her crinkly newspaper as if toasting its other side, and sniffed delicately. None of them had seen the banquet of Cherub laid out on the platform. Very suddenly, normality closed over them. The doors rolled shut. The noise of the train provided an excuse not to talk, as if it were embarrassed for them.

Tony simply stared, the flesh on his face slack, like old Hush Puppy shoes. There was definitely something wrong with him; he squinted up at the advertising, looking as if ads for Blistex were beyond his mental age. As the train approached Goodge Street, Michael wondered what on earth to do.

‘Look, Tony. I get off here. Will you be OK?’

Tony nodded yes. The train stopped and the doors opened. Michael got off. Tony followed him.

‘Do you want to see a doctor?’

Tony shook his head, no. Michael could think of nothing else to do, so he headed for the WAY OUT sign and the lift. Tony started to whistle, in a kind of deranged echoing drawl.

I don’t like this, Michael thought. He said airily, ‘So. Do you live around here, Tony?’

‘I live in Theydon Bois.’ Theydon Bois was at the end of the Central Line. This was the Northern.

‘So,’ Michael ventured. ‘You’re meeting someone?’ A coldness gathered around his heart.

‘No,’ said the Cherub in the same numb, faraway voice.

‘So where are you going?’ Why, Michael thought, does the underground always smell of asbestos and urine?

‘I don’t know. I don’t even have a ticket.’

They had reached the lifts. The windows in the metal doors looked like empty eye sockets. This was getting weird. ‘Look,’ Michael asked him, ‘if there’s something wrong, I’m not sure I can help you. Do have a phone with you?’

‘I don’t think so.’ Tony patted his tracksuit pockets.

Michael began to be afraid. This guy can bench-press 130 kilos. The elevator arrived filling the two windows with light as if they were eyes that had opened. The doors beeped and gaped but Michael did not get in.

‘You don’t want to go this way,’ said Michael. ‘You want to go back that direction.’

‘What I want doesn’t count,’ said Tony.

My God, thought Michael. He hasn’t blinked, not once.

Stand clear of the doors please said a cool, controlling voice. Michael decided it was best to get upstairs where there were people. He got in, Tony followed, and the doors trundled shut. They were alone.

Tony slipped his fingers under the spandex waistband, and pulled down both trousers and underwear, businesslike, as if finishing a warm-up.

Stop! thought Michael. Tony stopped. ‘Pull them up!’ said Michael. Tony did. The Cherub looked back at him, scowling slightly as if he couldn’t quite hear what was being said.

Jesus, thought Michael, this is what you get for fancying some guy at the gym: you chat away, you’re nice to him, and suddenly you’ve got a psychopath following you home. There was sweat on Michael’s upper lip. The lift did a little bounce and stopped, mimicking the sick sensation in Michael’s stomach.

The doors opened and Michael swept through them, fumbling to pull his season ticket out of his jacket pocket. He strode to the barriers, slipping his card into the slot like a kiss, nipped it free and pushed his way out and away. He could feel Tony’s eyes on his back as he escaped.

Michael thought and then stopped: you know he’s in trouble. It might be an insulin reaction, something like that. You can’t just leave him. He turned around. Tony was standing dazed behind the ticket barriers. What if he’s too ill to even know his way home? Michael sighed and walked back.

‘Is this something that happens to you sometimes? Are you diabetic, are you on any kind of medication?’ Michael was thinking schizophrenia. The ticket barriers were hunched between them like a line of American football players.

‘No,’ said Tony, as if from the bottom of a well.

‘Well look, the Central Line is back that way,’ Michael said. ‘Go back down and change at Tottenham Court Road.’ Michael glanced sideways; the guard was listening.

The guard was a young, handsome, burly man whom Michael had once halfway fancied, except for his unpleasant sneer. The guard was looking the other way, but his ears were pricked.

Tony said, mildly surprised. ‘Don’t you want to fuck me?’

Michael said, ‘No. I don’t.’

The guard covered his smile with an index finger.

Tony looked bruised. ‘You do,’ he insisted.

Michael began to talk for the benefit of the guard. ‘I’m sorry if you got that idea. Look, you’re in a bit of a state. My advice is to try to get back home and sort yourself out.’

The guard suddenly trooped forward, his smile broadening to a leer. ‘Bit off a bit more than we can chew, did we, sir?’

‘I think he’s on something and he’s been following me,’ said Michael.

‘Must be your lucky day,’ said the guard. He began to hustle Tony back from the barriers. ‘Come on, let the Professor be. He probably can’t afford you anyway.’ The guard had the cheek to turn and grin at Michael like he’d said something funny.

‘He’s not well,’ said Michael. Gosh, did he dislike that guard. But he needed him. The guard herded Tony back towards the lifts. Michael saw Tony look at him, with a suddenly stricken face. It was that panic that frightened Michael more than anything else. The panic meant that Tony needed Michael. For what? Something was out of whack.

Michael fled. He turned and walked as quickly as he could, away. He doesn’t know where I live, Michael thought, relieved. If I get away, I find another gym, and that’s the end of it. Michael’s stomach was shuddering as if he had run out of petrol. The tip of his penis was wet.

It had been raining, and the pavements were glossy like satin. A woman bearing four heavy bags from Tesco was looking at her boots; Michael scurried to make the lights and bashed into the bags, spinning them around in her grasp.

There was a shout from behind him. ‘Oi!’

Michael spun around, and saw the Cherub sprinting towards him. Michael knew, from the way his athlete’s stride suspended him in mid-air, that Tony had jumped the barriers.

Michael backed away, raising his arms against attack, terror bubbling up like yeast.

Keep away from me! Get back, go away!

And the street was empty. Tony was gone.

Michael blinked and looked around him, up and down the pavement. When he looked back, he saw the guard hobbling towards him, pressing a handkerchief to his face. He’d been hit.

‘Where did he go?’ the guard shouted at Michael, strands of spit between his lips. ‘Where the fuck did he go?’

‘I don’t know!’

‘Bastard!’

Michael tried to look at the guard’s lip.

The guard ducked away from Michael’s tender touch. He demanded, snarling, ‘What’s his name, where’s he from?’

Michael did not even have to think. ‘I’ve no idea. He just followed me.’

‘Oh yeah. Just followed you, did he? If I press charges, mate, you’ll bloody well have to remember.’

The guard pulled the handkerchief away and looked as if expecting to see something. He blinked. The handkerchief was clean, white and spotless.

This seemed to mollify him. ‘You better watch the kind of person you pick up, mate.’

Then the guard turned and proudly, plumply, walked away. For all your arrogance, Michael thought, in five years’ time you’ll be bald and fat-arsed.

Michael stood in the rain for a few moments, catching his breath. What, he thought, was that all about? Finally he turned and walked up Chenies Street, mostly because he had no place else to go, and he began to cry, from a mix of fear, frustration, boredom. Christ! All he did was go to the sauna. He didn’t need this, he really didn’t. He looked up at the yellow London sky. There were no stars overhead, just light pollution, a million lamps drowning out signals from alien intelligences.

Michael lived in what estate agents called a mansion block: an old apartment house. It was covered in scaffolding, being repaired. He looked up at his flat and saw that no lights were on. Phil wasn’t there again. So it would be round to Gigs again for a takeaway kebab and an evening alone. Involuntarily, Michael saw Tony’s naked thighs, the ridges of muscle.

He clunked his keys into the front door of his flat. The door was heavy and fireproofed and it made noises like an old man. Michael dumped his briefcase on the hall table and snapped on the living-room light.

The Cherub was sitting on the sofa.

‘Bloody hell!’ exclaimed Michael, and stumbled backwards. ‘What are you doing here?’

Tony sat with both hands placed on his knees. ‘I don’t know,’ he said in a mild voice.

‘How did you get in!’ The central light was bare and bleak.