Полная версия

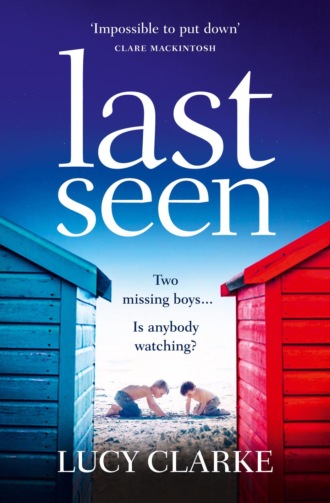

Last Seen: A gripping psychological thriller, full of secrets and twists

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Lucy Clarke 2017

Cover design by Heike Schüssler © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover photographs © Mary Schannen/Trevillion Images (children, beach); Hayden

Verry/Arcangel Images (beach huts); Naomi Roe/EyeEm/Getty Images (sky).

Lucy Clarke asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007563388

Ebook Edition © June 2017 ISBN: 9780007563395

Version: 2018-07-17

Dedication

To Darcy Wren, the newest addition to the family.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

1. Sarah

2. Isla

3. Sarah

4. Isla

5. Sarah

6. Isla

7. Sarah

8. Sarah

9. Isla

10. Sarah

11. Isla

12. Sarah

13. Isla

14. Sarah

15. Sarah

16. Isla

17. Sarah

18. Isla

19. Sarah

20. Isla

21. Sarah

22. Isla

23. Sarah

24. Isla

25. Sarah

26. Sarah

27. Isla

28. Sarah

29. Sarah

30. Isla

31. Sarah

32. Isla

33. Sarah

34. Sarah

35. Sarah

36. Isla

37. Isla

38. Sarah

39. Isla

40. Sarah

41. Sarah

42. Isla

43. Sarah

44. Isla

45. Sarah

46. Isla

47. Sarah

48. Isla

49. Sarah

50. Isla

51. Sarah

52. Isla

53. Sarah

54. Sarah

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

Chilling, gripping, and utterly compulsive, Lucy Clarke’s new novel is unmissable

A Q&A with Lucy Clarke

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Lucy Clarke

About the Publisher

Prologue

Salt water burns the back of my throat as I surface, coughing. My legs kick frantically, trying to propel me nearer the boat. The hull is close, whale-sized, solid. I lash out, white fingertips clawing at the side, but there’s nothing to grip and I go under again, mouth open, briny water shooting up my nose.

Suddenly there’s an iron hand around my arm, pulling, dragging me upwards. My kneecap smashes against the side of the boat as I’m hauled on board, a pool of water spilling from me. I blink salt water and tears from my eyes, staring into a face half hidden by a beard. A dark gaze meets mine; the man speaks quickly, asking questions, draping a blanket over my shoulders.

I say nothing. My whole body shakes beneath the stiff fabric.

I look down at my feet. They are pressed together, white, bloodless, impossibly pale. Beyond them, stacked in the centre of the boat, is a tower of briny, dark cages, where lobsters writhe, tails and claws snapping and clacking.

‘What happened?’ the man asks over and over, his voice sounding distant as if it’s an echo in my head.

I don’t answer – won’t take my eyes off the lobsters. They are not red as you see them in pictures, but black and shining, huge claws flecked with white. Can they breathe out of the sea, I wonder? Aren’t they drowning, right now, here in front of me? I want to throw them back into the water, watch them swim down to the sea bed. Their antennae quiver and flit as we motor towards the shallows.

There’s a sudden roar of a boat engine close by. My head snaps up in time to see a blur of orange flashing past: the lifeboat. For the first time I notice the small crowd gathered on the shoreline. My fingers dig into the blanket as I realize: they are looking for us.

Both of us.

I am shaking so hard my teeth clatter in my head. I look down at my hands, then slide them beneath my thighs. I know everything is different now. Everything has changed.

1. SARAH

DAY ONE, 6.15 A.M.

In the distance I can hear the light wash of waves folding on to shore. I lie still, eyes closed, but I can sense the dawn light filtering into the beach hut, slipping beneath the blinds ready to pull me into the new day. But I’m not ready. An uneasy feeling slides through my stomach.

I reach out to find Nick’s side of the bed empty, the sheet cool. He’s in Bristol, I remember. He has his pitch this morning. He left last night with a slice of birthday cake pressed into his hand. At that point Jacob was still smiling about the presents he’d been given for his seventeenth birthday. Nick has no idea what happened later.

A low flutter of panic beats in my chest: Will Jacob tell him?

I push myself upright in bed, my thoughts snapping and firing now. I can still feel the vibrations of Jacob’s footsteps storming across the beach hut, then the gust of air as the door slammed behind him, his birthday cards gliding to the ground like falling birds. I’d picked them up, carefully replacing each of them, until I reached the last – a homemade card with a photo glued to the front. I’d gripped its edges, imagining the satisfying tear of paper beneath my fingertips. I had made myself return it to the shelf, rearranging the cards so it was placed at the back.

I listen for the sound of Jacob’s breathing, waiting to catch the light hum of a snore – but all I can hear are the waves at the door. I straighten, fully alert now. Did I hear him come in last night? It’s impossible to sneak into the beach hut quietly. The door has to be yanked open where the wooden frame has swollen with rain; the sofa bed has to be skirted around in the dark; the wooden ladder to the mezzanine, where Jacob sleeps, creaks as it is climbed; and then there’s the slide and shuffle of his knees when he crawls to the mattress in the eaves.

Pulling back the covers, I clamber from the bed. In the dim haze I scan the tidy square of the beach hut for clues of my son: there are no trainers kicked off by the door; no jumper tossed on the sofa; no empty glasses or plates left on the kitchen counter, nor dusting of crumbs. The hut is immaculate, neat, just as I left it.

I ignore the faint pulse of pain in my head as I cross the beach hut in three steps, climbing the base of the ladder. It’s dark in the mezzanine – I’d pulled the blind over the porthole window and made Jacob’s bed before going to sleep myself. Usually the distinctive fug of a teenage boy lingers up here, but this morning the heaped body of my son is absent, the duvet smooth.

I squeeze my eyes shut and swear under my breath. What did I expect?

I don’t know why I let it happen, not on his birthday. I shouldn’t have risen to his challenge. I went too far. We both did. Diffuse, not antagonise, Nick is fond of telling me. (Thank you, Nick. I’d never have thought of that myself.)

When Jacob was little, Nick would always ask my opinion on what Jacob needed, how best to dress a cut on his knee, or whether he could do with a nap, or what he might prefer to eat. But, in the last few years, my confidence in knowing what my son needs has slipped away. In his company, I often find myself at an utter loss as to what to say – asking too many questions, or not the right ones. On the odd occasion that Jacob does confide in me, I feel like a desert-walker who has come across a freshwater lake, thirsting for closeness.

Last night, as Jacob swung round to face me, I couldn’t think what to say, what to do. Maybe it was because seventeen is like a line in the sand; he’d just stepped over it into adulthood – but I wasn’t ready. Maybe that’s why I said the things I did, trying to pull him back to me.

I descend the ladder now, feeling the full weight of my headache kicking in. I’m sure Jacob will have stayed out with his friends – he’ll probably roll in at mid-morning, a hangover worsening his mood. Yet still, I feel the tentacles of panic reaching, feeling their way through my chest.

Coffee. That’s what I need. I pump water into the kettle, then light the hob, listening to the rush of gas. As I wait for the water to boil, I have a strange, uncomfortable sensation that this is going to be my life one day: just me, alone, making coffee for one. It makes sweat prickle underarm, dread loosening my insides.

I reach out and snap on the battery-powered radio. A song blares into the hut – Jacob and I are always having radio wars, he switching it from Radio 4 to a station he likes, knowing I’ve still not learnt how to use the Memory button, so I must manually retune it to find my station again. But this morning, I like the noise and the thrash of guitars. I’ll leave it on. That way, when he comes back it’ll be playing.

Once I’ve made myself a coffee, I use the rest of the hot water to wash my face. There’s a toilet block nearby, but the sinks are usually mapped with sand or the white trails of spat-toothpaste. Diane and Neil next door have installed a water tank beneath their hut, and rigged up a heater from their solar panels so they can have hot running water at the flick of the tap. Isla thinks it’s an extravagance – another sign of the beach huts becoming too gentrified – but I’d laughed and said I’d be adding that to Nick’s To Do list.

I pat my face dry, then move to the windows, pulling up the blinds. Sea, sky and morning light spill into the hut and my breathing immediately softens. The early sun lies low to the horizon, the glassy sea tamed beneath it.

Stepping out on to the deck, the air is fresh and salted. I love this time of day before the breeze picks up and stirs white caps, when the light is soft against the water and the sand is empty of footprints. If Nick were here, he’d take his daily swim before leaving for the office, but right now he’ll be waking in a hotel room. I picture him shaving off the weekend’s stubble in a windowless en suite, then making an instant coffee with one of those silly miniature kettles. I don’t feel sorry that he’s there; he thrives on that kick of adrenalin that will be firing through him as he runs through the pitch for a final time, making sure he’s got just the right blend of humour, professionalism and hard facts. He’ll be brilliant, I know he will. His agency is pitching for the print advertising for a confectionery company that he’s been wooing for months. I’m keeping everything crossed for him. I know how much Nick needs it.

How much we need it.

Standing at the edge of the deck, I glance across to Isla’s hut. It stands shoulder to shoulder with ours – exactly five feet between them. In the summer that our boys turned seven, Jacob and Marley had fastened sheets above the shaded pathway running between the huts, calling it their Secret Sand Tunnel. Their games usually involved wanting to be in the water, or making dens in the wooded headland at the far end of the sandbank, so Isla and I were delighted to have them playing close by where we could hear the soft murmur of their chatter through the wooden walls of our huts, like mice in the eaves of a home.

In the clear morning light, I notice how tired Isla’s hut looks. The plywood shutters, which were hurriedly fixed across the windows last night, give the air of eviction, and the deck is empty of her faded floral sun-chair and barbecue. Several planks of decking are beginning to rot, mould lining the grooves. The yellow paintwork of the hut is peeling and flaking, and the sight saddens me, remembering how bright and vivid her hut was the first year she owned it – sherbet lemon yellow, she called the colour.

I feel my throat closing. Everything felt so fresh at the beginning. That first summer we met, I remember my father asking hopefully, ‘Is there a boy?’

I’d laughed. In a way, meeting Isla was like falling in love. We wanted to spend every free moment together. We would call each other after school, and have long, laughter-filled conversations that made my cheeks ache from smiling so hard, and my ear pink from being pressed close to the phone. My exercise books were filled with doodles of her name, and I’d find ways to bring her into conversation, just so she would feel present and real to me. Our friendship burst to life like a butterfly shedding its chrysalis: together we were bright and beautiful and soaring.

What happened to those two girls?

You didn’t want me here, Isla hissed last night before leaving to catch her flight.

I wondered if I’d feel guilty this morning. Regret the things I’d said to her.

I pull my shoulders back. I don’t.

I’m relieved she’s gone.

2. ISLA

It was so close to being perfect.

We were best friends.

We spent our summers living on a sandbank in beach huts next door to one another.

We fell pregnant in the same year – and gave birth to sons three weeks apart.

Our boys grew up together with the beach as their playground.

It seemed impossible, back then, to imagine that anything could come between us.

Yet perfect is a high spire to dance on – and below there’s nothing but a very long drop …

Summer 1991

A strong briny scent rose from the stacks of blackened lobster pots, where a flock of starlings hopped and chattered, iridescent feathers catching in the sunlight. At the harbour edge, the water gurgled and slopped. Sarah crouched down and dipped her forefinger into the water, then brought it to her lips and sucked it. She thought for a moment, then said, ‘Notes of engine oil, fish guts and swan shit.’

I grinned. I’d known Sarah for precisely one hour and forty-five minutes, but already we were friends. She had a good laugh – mischievous and surprisingly loud – yet there was something almost apologetic about the way she lifted a hand to her mouth as if to contain it.

Right now we were meant to be crammed into a sweltering studio taking part in a week-long drama workshop. I had my mum’s Reiki clients to blame for losing a whole week of the summer holidays; Sarah said she’d signed herself up as it was better than being at home. During the first break, we’d sat on the sun-warmed steps outside, drinking cans of Cherry Coke, and decided we wouldn’t be going back indoors.

Sarah placed her hands on the railings. Her bitten fingernails were painted pink, the polish faded at the edges. She looked across the water to the golden stretch of sand ahead of us. ‘Where’s that?’

‘Longstone Sandbank.’ It was flanked by a meandering natural harbour on one side, and on the other by the open sea. ‘You’ve never been?’

She shook her head. ‘We only moved here a month ago. Is it an island?’

‘Almost.’ The sandbank was no more than half a mile long, and was separated from the quay by a fast-moving channel of water. Dotted along its spine were a rabble of brightly coloured wooden beach huts. I always thought it looked as though the sandbank had tried its hardest to escape the mainland – and it had succeeded, except for the slimmest touch of land still tethering it to a wooded headland at its far end.

‘How do you get there?’

‘By boat,’ I said, nodding towards the ferry that was bobbing across the harbour, orange fenders strapped to its sides. The engine growled against the running tide as it motored towards the quayside. We watched as the round-faced captain leant out to loop a rope around a thick wooden post.

‘Wanna go there?’ I asked.

Sarah’s green eyes glittered as they met mine. ‘Yes.’

We climbed on to the wooden boat, handing the captain our fifty-pence pieces, and moved to the bench at the back. Kneeling up on the seat, we rested our chins on top of folded arms so we could watch the wake the ferry created as it pulled away.

I glanced across at Sarah. The sun illuminated her clear, smooth face, and the delicate curve of her small mouth. She grinned at me. ‘Who knew drama club would be so much fun?’

The ferry crossing only took a few minutes and we hopped from the boat and moved down the rickety jetty, our sandals clanking against the wooden planks. Reaching the beach, Sarah’s gaze flitted over the huts as she exclaimed, ‘They’re like little houses. Look! They have proper kitchens – and beds!’

‘You can sleep in them during the summer,’ I told her, pointing out a hut with a wooden ladder leading up to a mezzanine. ‘Imagine waking up here!’

A low, rhythmic boom hinted at the sea that lay on the other shore of the sandbank, so we left the harbour behind and squeezed between two huts, stepping over a set of oars and skirting a deflated dinghy. Immediately the breeze was stronger, blown onshore in salty gusts. Whitecaps ducked and dived, driving small waves to break on the shore. Rocky groynes punctuated the beach, creating a series of small bays.

We kicked off our shoes and walked with our arms linked, tramping through the thick, warm sand. Sarah was a head shorter than me, but she walked with long strides and our steps fell into an easy rhythm. There were pockets of activity everywhere: two young girls buckled into life jackets were dragging a kayak to the shore; an older woman standing in the shallows threw a stick for a muscular, bounding dog; a man in a panama hat struggled to put up a windbreak in the fine sand, using a pebble for a hammer. We passed a family eating brunch at a picnic table, their bare feet dug into the sand, a pile of napkins secured from the breeze by a large pebble. At the hut next door a group of teenage boys lounged bare-chested and tanned, two guitars leant against sun-chairs. I nudged Sarah in the ribs and she smiled into her chin.

Surprisingly, many of the huts were closed, their blinds drawn. I wondered where their owners were – what they could possibly be doing that was better than being here. They looked odd, those shuttered huts, secretive shadows in the brilliant midday sun.

After some time, a craggy headland ended the row of huts and the beach thinned as it wrapped around crumbling sandstone cliffs. We scrambled over a rocky groyne that separated one deserted bay from the next, and walked on the shoreline, avoiding the dark piles of seaweed flagging on the sand.

Sarah paused, turning to face me. ‘Shall we swim?’

I glanced around us; the bay was empty, the water a tantalizing blue. I grinned as I wriggled out of my T-shirt and cut-offs, leaving me in mismatched underwear.

Sarah shrugged off her dress, grabbed my hand, and together we ran towards the water.

My breath caught at the first grip of cold around my ankles. Sarah squealed as a rush of white water engulfed our middles. When a wave came, I dived through it, cold squeezing a scream from my lungs. Beneath the water I glided, the rest of the world closing out. My skin came alive with the bite of the sea, the sting of the salt.

When there was no more air left in my lungs, I broke through the surface, hair slick to my head. The sea fizzed and breathed around me.

Sarah was laughing with her head tipped back.

We let the sea toy with us – lifting us up, then sucking us back with each shelf of water.

‘Let’s catch this wave,’ I said, paddling for a small peak and trying to bodysurf into shore, but I wasn’t quick enough and it passed beneath me. I trod water waiting for the next and, when it came, we both kicked feverishly whilst striking out with our arms. We were rewarded as the wave propelled us forwards, Sarah whooping as we travelled. The wave broke early in a charge of foam and we were sent flailing, legs tangled about arms like rag dolls. I felt myself rolled along the sea bed, my underwear flimsy protection against the ride, and we both surfaced gasping and laughing. We waded out, staggering up the beach.

An older boy with thick dark hair, who I hadn’t noticed earlier, was fishing on the rocks at the edge of the bay. He watched us closely, his gaze both serious and curious. I glanced sideways at Sarah and found she was staring right back at him.

I shivered. We didn’t have towels, so we stood with our arms outstretched to salute the sun, like my mother did in her yoga practice.