Полная версия

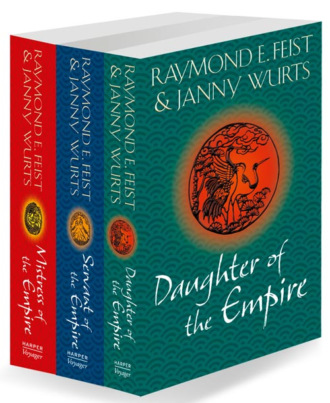

The Complete Empire Trilogy: Daughter of the Empire, Mistress of the Empire, Servant of the Empire

In hoarse tones Mara said, ‘I wish to rest. The journey was tiring. Leave now.’ The maids left the room at once, but the three retainers all hesitated. Mara said, ‘What is it?’

Nacoya answered, ‘There is much to be done – much that may not wait, Mara-anni.’

The use of the diminutive of her name was intended in kindness, but to Mara it became a symbol of all she had lost. She bit her lip as the hadonra said, ‘My Lady, many things have gone neglected since … your father’s death. Many decisions must be made soon.’

Keyoke nodded. ‘Lady, your upbringing is lacking for one who must rule a great house. You must learn those things we taught Lanokota.’

Miserable with memories of the rage she had exchanged with her father the night before she had left, Mara was stung by the reminder that her brother was no longer heir. Almost pleading, she said, ‘Not now. Not yet.’

Nacoya said, ‘Child, you must not fail your name. You –’

Mara’s voice rose, thick with emotions held too long in check. ‘I said not yet! I have not observed a time of mourning! I will hear you after I have been to the sacred grove.’ The last was said with a draining away of anger, as if the little flash was all the energy she could muster. ‘Please,’ she added softly.

Ready to retire, Jican stepped back, absently plucking at his livery. He glanced at Keyoke and Nacoya, yet both of them held their ground. The Force Commander said, ‘Lady, you must listen. Soon our enemies will move to destroy us. The Lord of the Minwanabi and the Lord of the Anasati both think House Acoma defeated. Neither should know you did not take final vows for a few days more, but we cannot be sure of that. Spies may already have carried word that you have returned; if so, your enemies are even now plotting to finish this house once and finally. Responsibilities cannot be put off. You must master a great deal in a short time if there is to be any hope of survival for the Acoma. The name and honour of your family are now in your hands.’

Mara tilted her chin in a manner unchanged from her childhood. She whispered, ‘Leave me alone.’

Nacoya stepped to the dais. ‘Child, listen to Keyoke. Our enemies are made bold by our loss, and you’ve no time for self-indulgence. The education you once received to become the wife of some other household’s son is inadequate for a Ruling Lady.’

Mara’s voice rose, tension making the blood sing in her ears. ‘I did not ask to be Ruling Lady!’ Dangerously close to tears, she used anger to keep from breaking. ‘Until a week ago, I was to be a sister of Lashima, all I wished for in this life! If the Acoma honour must rely upon me for revenge against the Minwanabi, if I need counsel and training, all will wait until I have visited the sacred grove and done reverence to the memories of the slain!’

Keyoke glanced at Nacoya, who nodded. The young Lady of the Acoma was near breaking, and must be deferred to, but the old nurse was ready to deal with even that. She said, ‘All is prepared for you in the grove. I have presumed to choose your father’s ceremonial sword to recall his spirit, and Lanokota’s manhood robe to recall his.’ Keyoke motioned to where the two objects lay atop a richly embroidered cushion.

Seeing the sword her father wore at festivals and the robe presented to her brother during his ceremony of manhood was more than the exhausted, grief-stricken girl could bear. With tears rising, she said, ‘Leave me!’

The three hesitated, though to disobey the Lady of the Acoma was to risk punishment even unto death. The hadonra was first to turn and quit his mistress’s quarters. Keyoke followed, but as Nacoya turned to go, she repeated, ‘Child, all is ready in the grove.’ Then slowly she slid the great door closed.

Alone at last, Mara allowed the tears to stream down her cheeks. Yet she held her sobbing in check as she rose and picked up the cushion with the sword and robe upon it.

The ceremony of mourning was a private thing; only family might enter the contemplation glade. But under more normal circumstances, a stately procession of servants and retainers would have marched with surviving family members as far as the blocking hedge before the entrance. Instead a single figure emerged from the rear door of her quarters. Mara carried the cushion gently, her white robe wrinkled and dirty where the hem dragged in the dust.

Even deaf and blind she would have remembered the way. Her feet knew the path, down to the last stone fisted into the gnarled ulo tree root beside the ceremonial gate. The thick hedge that surrounded the grove shielded it from observation. Only the Acoma might walk here, save a priest of Chochocan when consecrating the grove or the gardener who tended the shrubs and flowers. A blocking hedge faced the gate, preventing anyone outside from peering within.

Mara entered and hurried to the centre of the grove. There, amid a sculptured collection of sweet-blossomed fruit trees, a tiny stream flowed through the sacred pool. The rippled surface reflected the blue-green of the sky through curtains of overhanging branches. At water’s edge a large rock sat embedded in the soil, worn smooth by ages of exposure to the elements; the shatra bird of the Acoma was once carved deeply on its surface, but now the crest was barely visible. This was the family’s natami, the sacred rock that embodied the spirit of the Acoma. Should the day come when the Acoma were forced to flee these lands, this one most revered possession would be carried away and all who bore the name would die protecting it. For should the natami fall into the hands of any other, the family would be no more. Mara glanced at the far hedge. The three natami taken by Acoma ancestors were interred under a slab, inverted so their carved crests would never see sunlight again. Mara’s forebears had obliterated three families in the Game of the Council. Now her own stood in peril of joining them.

Next to the stone a hole had been dug, the damp soil piled to one side. Mara placed the cushion with her father’s sword and her brother’s robe within. With bare hands she pushed the earth back into the hole, patting it down, unmindful as she soiled her white robe.

Then she sat back on her heels, caught by the sudden compulsion to laugh. A strange, detached giddiness washed over her and she felt alarm. Despite this being the appointed place, tears and pain so long held in check seemed unwilling to come.

She took a breath and stifled the laughter. Her mind flashed images and she felt hot flushes rush up her breasts, throat, and cheeks. The ceremony must continue, despite her strange feelings.

Beside the pool rested a small vial, a faintly smoking brazier, a tiny dagger, and a clean white gown. Mara lifted the vial and removed the stopper. She poured fragrant oils upon the pool, sending momentary shimmers of fractured light across its surface. Softly she said, ‘Rest, my father. Rest, my brother. Come to your home soil and sleep with our ancestors.’

She laid the vial aside and with a jerk ripped open the bodice of her robe. Despite the heat, chill bumps roughened her small breasts as the breeze struck suddenly exposed, damp skin. She reached up and again ripped her gown, as ancient traditions were followed. With the second tear she cried out, a halfhearted sound, little better than a whimper. Tradition demanded the show of loss before her ancestors.

Again she tore her robe, ripping it from her left shoulder so it hung half to her waist. But the shout that followed held more anger at her loss than sorrow. With her left hand she reached up and tore her gown from her right shoulder. This time her sob was full-throated as pain erupted from the pit of her stomach.

Traditions whose origins were lost in time at last triggered a release. All the torment she had held in check came forth, rushing up from her groin through her stomach and chest to issue from her mouth as a scream. The sound of a wounded animal rang in the glade as Mara gave full vent to her anger, revulsion, torment and loss.

Shrieking with sorrow, nearly blinded with tears, she plunged her hand into the almost extinguished brazier. Ignoring the pain of the few hot cinders there, she smeared the ashes across her breasts and down her exposed stomach. This symbolized that her heart was ashes, and again sobs racked her body as her mind sought final release from the horror left by the murder of her father, brother, and hundreds of loyal warriors. Her left hand shot out and grabbed dirt from beside the natami. She smeared the damp soil in her hair and struck her head with her fist. She was one with Acoma soil, and to that soil she would return, as would the spirits of the slain.

Now she struck her thigh with her fist, chanting the words of mourning, almost unintelligible through her crying. Rocking back and forth upon her knees, she wailed in sorrow.

Then she seized the tiny metal dagger, a family heirloom of immense value, used only for this ceremony over the ages. She drew the blade from its sheath and cut herself across the left arm, the hot pain a counterpoint to the sick ache in her chest.

She held the small wound over the pool, letting drops of blood fall to mix with the water, as tradition dictated. Again she tore at her robe, ripping all but a few tatters from her body. Naked but for a loincloth, she cast the rags away with a strangled cry. Pulling her hair, forcing pain to cleanse her grief, she chanted ancient words, calling her ancestors to witness her bereavement. Then she threw herself across the fresh soil over the place of interment and rested her head upon the family natami.

With the ceremony now complete, Mara’s grief flowed like the water streaming from the pool, carrying her tears and blood to the river, thence to the distant sea. As mourning eased away pain, the ceremony would eventually cleanse her, but now was the moment of private grief when tears and weeping brought no shame. And Mara descended into grief as wave after wave of sorrow issued from the deepest reservoir within her soul.

A sound intruded, a rustling of leaves as if someone moved through the tree branches above her. Caught up in grief, Mara barely noticed, even when a dark figure dropped to land next to her. Before she could open her eyes, powerful fingers yanked on her hair. Mara’s head snapped back. Jolted by a terrible current of fear, she struggled, half glimpsing a man in black robes behind her. Then a blow to the face stunned her. Her hair was released and a cord was passed over her head. Instinctively she grabbed at it. Her fingers tangled in the loop that should have killed her in seconds, but as the man tightened the garrotte, her palm prevented the knot in the centre from crushing her windpipe. Still she couldn’t breathe. Her attempt to shout for aid was stifled. She tried to roll away, but her assailant jerked upon the cord and held her firmly in check. A wrestler’s kick learned from her brother earned her a mocking half-laugh, half-grunt. Despite her skill, Mara was no match for the assassin.

The cord tightened, cutting painfully into her hand and neck. Mara gasped for breath, but none came and her lungs burned. Struggling like a fish on a gill line, she felt the man haul her upright. Only her awkward grip on the cord kept her neck from breaking. Mara’s ears sang from the pounding of her own blood within. She clawed helplessly with her free hand. Her fingers tangled in cloth. She yanked, but was too weak to overbalance the man. Through a roar like surf, she heard the man’s laboured breathing as he lifted her off the ground. Then, defeated by lack of air, her spirit fell downwards into darkness.

• Chapter Two • Evaluations

Mara felt wetness upon her face.

Through the confusion of returning senses, she realized Papewaio was gently cradling her head in the crook of his arm as he moistened her face with a damp rag. Mara opened her mouth to speak, but her throat constricted. She coughed, then swallowed hard against the ache of injured neck muscles. She blinked, and struggled to organize her thoughts; but she knew only that her neck and throat hurt terribly and the sky above looked splendid beyond belief, its blue-green depths appearing to fade into the infinite. Then she moved her right hand; pain shot across her palm, jolting her to full memory.

Almost inaudibly she said, ‘The assassin?’

Papewaio inclined his head toward something sprawled by the reflecting pool. ‘Dead.’

Mara turned to look, ignoring the discomfort of her injuries. The corpse of the killer lay on one side, the fingers of one hand trailing in water discoloured with blood. He was short, reed-thin, of almost delicate build, and clad simply in a black robe and calf-length trousers. His hood and veil had been pulled aside, revealing a smooth, boyish face marked by a blue tattoo upon his left cheek – a hamoi flower stylized to six concentric circles of wavy lines. Both hands were dyed red to the wrists. Mara shuddered, still stinging from the violence of those hands upon her flesh.

Papewaio helped her to her feet. He tossed away the rag, torn from her rent garment, and handed her the white robe intended for the end of the ceremony. Mara clothed herself, ignoring the stains her injured hands made upon the delicately embroidered material. At her nod, Papewaio escorted her from the glade.

Mara followed the path, its familiarity no longer a comfort. The cruel bite of the stranger’s cord had forced her to recognize that her enemies could reach even to the heart of the Acoma estates. The security of her childhood was forever gone. The dark hedges surrounding the glade now seemed a haven for assassins, and the shade beneath the wide limbs of the ulo tree carried a chill. Rubbing the bruised and bloody flesh of her right hand, Mara restrained an impulse to bolt in panic. Though terrified like a thyza bird at the shadow of a golden killwing as it circles above, she stepped through the ceremonial gate with some vestige of the decorum expected of the Ruling Lady of a great house.

Nacoya and Keyoke waited just outside, with the estate gardener and two of his assistants. None spoke but Keyoke, who said only, ‘What?’

Papewaio replied with grim brevity. ‘As you thought. An assassin waited. Hamoi tong.’

Nacoya extended her arms, gathering Mara into hands that had soothed her hurts since childhood, yet for the first time Mara found little reassurance. With a voice still croaking from her near strangulation, she said, ‘Hamoi tong, Keyoke?’

‘The Red Hands of the Flower Brotherhood, my Lady. Hired murderers of no clan, fanatics who believe to kill or be killed is to be sanctified by Turakamu, that death is the only prayer the god will hear. When they accept a commission they vow to kill their victims or die in the attempt.’ He paused, while the gardener made an instinctive sign of protection: the Red God was feared. With a cynical note, Keyoke observed, ‘Yet many in power understand that the Brotherhood will offer their unique prayer only when the tong has been paid a rich fee.’ His voice fell to almost a mutter as he added, ‘And the Hamoi are very accommodating as to whose soul shall offer that prayer to Turakamu.’

‘Why had I not been told of these before?’

‘They are not part of the normal worship of Turakamu, mistress. It is not the sort of thing fathers speak of to daughters who are not heirs.’ Nacoya’s voice implied reprimand.

Though it was now too late for recriminations, Mara said, ‘I begin to see what you meant about needing to discuss many things right away.’ Expecting to be led away, Mara began to turn toward her quarters. But the old woman held her; too shaken to question, Mara obeyed the cue to remain.

Papewaio stepped away from the others, then dropped to one knee in the grass. The shadow of the ceremonial gate darkened his face, utterly hiding his expression as he drew his sword and reversed it, offering the weapon hilt first to Mara. ‘Mistress, I beg leave to take my life with the blade.’

For a long moment Mara stared uncomprehendingly. ‘What are you asking?’

‘I have trespassed into the Acoma contemplation glade, my Lady.’

Overshadowed by the assassination attempt, the enormity of Papewaio’s act had not registered upon Mara until this instant. He had entered the glade to save her, despite the knowledge that such a transgression would earn him a death sentence without appeal.

As Mara seemed unable to respond, Keyoke tried delicately to elaborate on Pape’s appeal. ‘You ordered Jican, Nacoya, and myself not to accompany you to the glade, Lady. Papewaio was not mentioned. He hid himself near the ceremonial gate; at the sound of a struggle he sent the gardener to fetch us, then entered.’

The Acoma Force Commander granted his companion a rare display of affection; for an instant the corners of his mouth turned up, as if he acknowledged victory after a difficult battle. Then his hint of a smile vanished. ‘Each one of us knew such an attempt upon you was only a matter of time. It is unfortunate that the assassin chose this place; Pape knew the price of entering the glade.’

Keyoke’s message to Mara was clear: Papewaio had affronted Mara’s ancestors by entering the glade, earning himself a death sentence. But not to enter would have entailed a fate far worse. Had the last Acoma died, every man and woman Papewaio counted a friend would have become houseless persons, little better than slaves or outlaws. No warrior could do other than Papewaio had done; his life was pledged to Acoma honour. Keyoke was telling Mara that Pape had earned a warrior’s death, upon the blade, for choosing life for his mistress and all those he loved at the cost of his own life. But the thought of the staunch warrior dying as a result of her own naïveté was too much for Mara. Reflexively she said, ‘No.’

Assuming this to mean he was denied the right to die without shame, Papewaio bent his head. Black hair veiled his eyes as he flipped his sword, neatly, with no tremor in his hands, and drove the blade into the earth at his Lady’s feet. Openly regretful, the gardener signalled his two assistants. Carrying rope, they hurried forward to Papewaio’s side. One began to bind Papewaio’s hands behind him while the other tossed a long coil of rope over a stout tree branch.

For a moment Mara was without comprehension, then understanding struck her: Papewaio was being readied for the meanest death, hanging, a form of execution reserved for criminals and slaves. Mara shook her head and raised her voice. ‘Stop!’

Everyone ceased moving. The assistant gardeners paused with their hands half-raised, looking first to the head gardener, then to Nacoya and Keyoke, then to their mistress. They were clearly reluctant to carry out this duty, and confusion over their Lady’s wishes greatly increased their discomfort.

Nacoya said, ‘Child, it is the law.’

Gripped by an urge to scream at them all, Mara shut her eyes. The stress, her mourning, the assault, and now this rush to execute Papewaio for an act caused by her irresponsible behaviour came close to overwhelming her. Careful not to burst into tears, Mara answered firmly. ‘No … I haven’t decided.’ She looked from face to impassive face and added, ‘You will all wait until I do. Pape, take up your sword.’

Her command was a blatant flouting of tradition; Papewaio obeyed in silence. To the gardener, who stood fidgeting uneasily, she said, ‘Remove the assassin’s body from the glade.’ With a sudden vicious urge to strike at something, she added, ‘Strip it and hang it from a tree beside the road as a warning to any spies who may be near. Then cleanse the natami and drain the pool; both have been defiled. When all is returned to order, send word to the priests of Chochocan to come and reconsecrate the grove.’

Though all watched with unsettled eyes, Mara turned her back. Nacoya roused first. With a sharp click of her tongue, she escorted her young mistress into the cool quiet of the house. Papewaio and Keyoke looked on with troubled thoughts, while the gardener hurried off to obey his mistress’s commands.

The two assistant gardeners coiled the ropes, exchanging glances. The ill luck of the Acoma had not ended with the father and the son, so it seemed. Mara’s reign as Lady of the Acoma might indeed prove brief, for her enemies would not rest while she learned the complex subtleties of the Game of the Council. Still, the assistant gardeners seemed to silently agree, such matters were in the hands of the gods, and the humble in life were always carried along in the currents of the mighty as they rose and fell. None could say such a fate was cruel or unjust. It simply was.

The moment the Lady of the Acoma reached the solitude of her quarters, Nacoya took charge. She directed servants who bustled with subdued efficiency to make their mistress comfortable. They prepared a scented bath while Mara rested on cushions, absently fingering the finely embroidered shatra birds that symbolized her house. One who did not know her would have thought her stillness the result of trauma and grief; but Nacoya observed the focused intensity of the girl’s dark eyes and was not fooled. Tense, angry, and determined, Mara already strove to assess the far-reaching political implications of the attack upon her person. She endured the ministrations of her maids without her usual restlessness, silent while the servants bathed her and dressed her wounds. A compress of herbs was bound around her bruised and lacerated right hand. Nacoya hovered anxiously by while Mara received a vigorous rub by two elderly women who had ministered to Lord Sezu in the same manner. Their old fingers were surprisingly strong; knots of muscular tension were sought out and gradually kneaded away. Afterwards, clothed in clean robes, Mara still felt tired, but the attentions of the old women had eased away nervous exhaustion.

Nacoya brought chocha, steaming in a fine porcelain cup. Mara sat before a low stone table and sipped the bitter drink, wincing slightly as the liquid aggravated her bruised throat. In the grove she had been too shocked by the attack to feel much beyond a short burst of panic and fear. Now she was surprised to discover herself too wrung out to register any sort of reaction. The slanting light of afternoon brightened the paper screens over the windows, as it had throughout her girlhood. Far off, she could hear the whistles of the herdsmen in the needra meadows, and near at hand, Jican’s voice reprimanding a house slave for clumsiness. Mara closed her eyes, almost able to imagine the soft scratch of the quill pen her father had used to draft instructions to distant subordinates; but Minwanabi treachery had ended such memories forever. Reluctantly Mara acknowledged the staid presence of Nacoya.

The old nurse seated herself on the other side of the table. Her movements were slow, her features careworn. The delicate seashell ornaments that pinned her braided hair were fastened slightly crooked, as reaching upwards to fix the pin correctly became more difficult with age. Although only a servant, Nacoya was well versed in the arts and subtlety of the Game of the Council. She had served at the right hand of Lord Sezu’s lady for years, then raised his daughter after the wife’s death in childbirth. The old nurse had been like a mother to Mara. Sharply aware that the old nurse was waiting for some comment, the girl said, ‘I have made some grave errors, Nacoya.’

The nurse returned a curt nod. ‘Yes, child. Had you granted time for preparation, the gardener would have inspected the grove immediately before you entered. He might have discovered the assassin, or been killed, but his disappearance would have alerted Keyoke, who could have had warriors surround the glade. The assassin would have been forced to come out or starve to death. Had the Hamoi murderer fled the gardener’s approach and been lurking outside, your soldiers would have found his hiding place.’ The nurse’s hands tightened in her lap, and her tone turned harsh. ‘Indeed, your enemy expected you to make mistakes … as you did.’

Mara accepted the reproof, her eyes following the lazy curls of steam that rose from her cup of chocha. ‘But the one who sent the killer erred as much as I.’

‘True.’ Nacoya squinted, forcing farsighted vision to focus more clearly upon her mistress. ‘He chose to deal the Acoma a triple dishonour by killing you in your family’s sacred grove, and not honourably with the blade, but by strangulation, as if you were a criminal or slave to die in shame!’