Полная версия

Wicked Beyond Belief: The Hunt for the Yorkshire Ripper

Hoban loved his family, and the feeling was mutual, but always, always in the eyes of his wife and two boys, the job came first. Richard Hoban remembers being carried in his father’s arms at the age of three on a family shopping trip in an arcade in Leeds when they witnessed a jewel robbery. ‘I was slung into the arms of my mother and off he went, hurtling after this jewellery thief and caught him. It was the last we saw of him for several hours.’

At home, Richard, his brother David and their mother would become Hoban’s telephone answering service, which included taking messages from informants. ‘We would be “Leeds 66815” – the number is etched on my memory. The snouts would say: “Is that Richard? Tell your dad something’s going to happen, tell him to get in touch with me and it will cost him ten bob or a couple of quid or whatever.” Occasionally you’d get someone ringing up who’d crossed my Dad’s path at some time and they’d tell me what they were going to do to me or David or my mother.’ As well as the household’s phone being used in the fight against crime, the family blue and white Triumph Herald was used to chase criminals. Once Hoban crashed it into a bridge trying to stop someone escaping his clutches.

He loved being where the action was: nabbing villains, being involved in car chases, arresting criminals at an armed bank robbery. Even at the rank of detective superintendent, as the deputy coordinator of the regional crime squad a decade earlier, he made sure he was at the sharp end, posing undercover as a taxi driver complete with cap when a notorious gang was under surveillance. The gang had him drive from Leeds to Grimsby via a nightclub in Doncaster. He had to decline an invitation to go into the nightclub, because the moment the gang got out of the vehicle it was commandeered by a group of drunken sailors who wanted to be taken back to Grimsby. He then returned and collected the gang when they had finished drinking. Later the undercover squad of detectives, secretly guarding Hoban, were treated by him to a night out on the proceeds of the fare for the long trip, paid by the gang. He wasn’t exaggerating when he told a journalist: ‘It’s more than just a job – coppering is a way of life, a hobby, everything – I wouldn’t swap it for anything.’

While Hoban’s abilities as a detective were considerable, his critics could point to his relatively narrow experience in terms of large-scale policing. As one of the biggest constabularies in the country, the new West Yorkshire force would provide plenty of opportunity for qualified men to move up the promotion ladder. All things being equal, Hoban should have been one of those. But his detractors, all of whom came from the old West Yorkshire force, believed his driven personality was a major barrier to him obtaining higher rank. Some accused him of self-aggrandisement, always pushing himself forward – anxious to have his photograph taken for the Yorkshire Post or the northern editions of the national press; or keen to offer himself for interviews on television. From Hoban’s viewpoint, communicating with the public was a big part of the job. He was well known throughout Leeds as the city’s top detective, and he used this image to speak directly to the man or woman in the street, in the hope that they might come forward with some vital clue. A few very senior but quite impartial colleagues saw his administrative weakness as a major flaw.

Some senior West Riding detectives had worked closely with both Hoban on the regional crime squad based at Brotherton House in Leeds and the new ACC (crime) George Oldfield, the senior detective in the West Riding force. They viewed Oldfield, a former wartime Royal Navy petty officer, as the better team player. ‘Dennis was a seat of his pants operator, always a bit fly and capable of going off at tangents. He had a single objective – to catch criminals, and at that he was brilliant. But a modern police force needs people with a broader perspective.’

This professional criticism of Dennis Hoban was a reflection of the different cultures of policing in the bigger towns and cities. It also reflected different methods of tackling serious crime. The West Riding’s operational procedures for solving murders were radically different from those in operation within Leeds before the 1974 amalgamation. The old West Riding force had a paper-led system which was time consuming in the short term but in the long term garnered evidence in statement form from witnesses which would in a protracted inquiry prove crucial in mounting a successful prosecution. Prior to amalgamation, most provincial borough and county force murder inquiries involved bringing in a senior detective from Scotland Yard, because historically the Metropolitan Police was the only force in the country with wide experience of dealing with homicides. County forces tended to adopt the Metropolitan Police way of doing things. The bigger cities, like Leeds, Bradford and Manchester, had the manpower and experience to run murder inquiries without help from the Yard. Each had its own system for tackling murders. The Manchester force took very few statements in a major crime investigation until they were needed for court proceedings. In Leeds, Hoban operated a similar system. Like a general on the battlefield, he was in charge of strategy. He relied on his middle managers to keep him briefed on those lines of inquiry most likely to yield results. He never immersed himself in detail until it was absolutely essential, and as a consequence rarely needed to read reams of paperwork.

Most murders in Britain are solved quickly because there is some domestic involvement such as the victim being known to the killer. In Leeds, Hoban could throw a hundred officers into a murder inquiry and blitz the local area in terms of finding crucial evidence. Over time in Leeds, this method proved very efficient because it found the link between the victim and the killer. Hoban solved nearly all the fifty murders he had tackled, but by the time he was moved to force headquarters at Wakefield, the killer of McCann and Jackson still totally eluded him. He realized that the man who killed these two women had struck at random. They had simply been unlucky victims. In terms of solving murders, finding killers without a personal motive was a nightmare for everyone – the public as well as the police.

One senior officer from outside Yorkshire reckoned that Hoban was the best detective he ever met: ‘He had that great amalgamation of all those qualities that it takes. He had an ability to pick, which is very important. He had an ability to listen to you even though he might not agree with you. He made you feel comfortable in his presence. He had all the qualities you require in a man who is trying to do that job. He has confidence in his team, to let his team deal with the dross and to say to him: “Here you are, boss – this is the one you should look at.” Not for him to be in the sea of what is going on but to be looking at the one aspect really likely to produce a result. He had the ability to pick people round him who were really good and that is a great quality in any senior policeman: “Can you pick the people who’ve got qualities you haven’t got that can support you well?”

‘Dennis Hoban was a very pragmatic, hands-on murder investigator. A lot of people say he overplayed the PR, but I personally don’t believe that. Crime detection is about the senior detective being good at PR. There are all those members of the public out there who can help you, yet you have only a few men to make inquiries, so that mobilization of the public is very important, and Dennis did it.’

In Hoban’s view, public support was at its most crucial in murder inquiries. As a detective, he had too often seen the results of the sudden impulse to kill. As a father, he was absolutely strict with his own sons and he despaired of the way young people were surrounded by violence, seeing it almost as an illness of society: ‘The trouble is that youngsters today see violence all around them, every day. It’s becoming the norm. They see a man getting hit over the head with an iron bar on a television programme, and the man shakes his head and walks away. But it’s not like that in real life. What can and does happen is that the man probably ends up with a steel plate in his head, brain damage, deafness or blindness. He loses his job and his family can break up. I have come across many a criminal who, when faced with the reality of his crime, has had a change of heart. The criminal should be made to pay for his crime. I am a believer in the deterrent effect of hanging, I believe it works.’

Each year Leeds saw, on average, ten homicides, most of them solved because of some link between killer and victim which Hoban’s team managed to uncover. The difficulty came when no such link was found. Most colleagues who knew Hoban well felt he had an extraordinary knack for solving murders and getting the best out of his men, often working on hunches which proved amazingly accurate. He rarely pulled rank, because he didn’t need to, and he displayed remarkable qualities of leadership because he earned the respect of his troops as both man and detective. His key ability was to weigh up the suspect psychologically, a knack which proved him right time and time again. These hunches were the result of years of experience, observation and a deep understanding of people. He always gave credit to the team who worked for him, leading from the front, showing a sense of humour and often pushing himself for forty-eight hours at a stretch, particularly with serious crimes like murders, where he knew you had to crack it early while people’s memories were still fresh.

A perfect example of his approach came in the early 1970s when he masterminded a murder inquiry and threw every resource he had at the problem for thirty-three days. Within a few minutes of the body of Mrs Phyllis Jackson, a fifty-year-old mother of two, being found brutally murdered at her home in Dewsbury Road, Leeds, a master plan for homicide investigations was put into operation. A vehicle equipped with a radio went to the murder scene to act as a control point and a hundred detectives were drafted in immediately. There was evidence she had been raped.

The answer would most probably lie close to the victim and her lifestyle – find the motive, then find the link to the killer. A murder incident room was opened at the police HQ in Westgate. One vital clue emerged from the post-mortem. Mrs Jackson had been strangled, then stabbed with a knife which probably had a serrated edge. A massive search began that included bringing in the army with mine detectors, which made for great photographs and local television news footage that Hoban knew would keep the murder in the public eye. Corporation workmen searched the drains, and every conceivable place where a fleeing killer might have hidden the murder weapon was searched. Much of this was standard in an unsolved homicide, but the procedure was galvanized by Hoban’s sense of urgency, enthusiasm and inspiration.

Experience had shown him the killer was most likely a local man. The victim lived in a new housing scheme within a development area, but with no local facilities to attract people from outside – no cinema, shops or places of entertainment. Anyone present in the area was most likely to be there because they were acquainted with someone locally rather than having stumbled on the place by accident. When the search for the weapon proved fruitless, Hoban tried another tack. A survey of every home in the vicinity was carried out. Every day detectives went to local houses armed with a questionnaire to establish exactly where every man in each household had been at the time of the murder and to see if anyone had noticed anything suspicious.

By such painstaking methods are murders traditionally solved. Reports filtered in about other attacks on women in the city, and while each was carefully probed, none could be linked to the murder of Phyllis Jackson either by method or motive. Fear among women in the city became palpable. There was a run on people buying door locks and safety chains, and stocks at hardware shops ran out in some areas. Special lifeline buzzers were distributed to the elderly so they could summon help if frightened. Some two hundred calls a day were coming in to the incident room offering information, and each call was followed up by detectives working long hours. At that time police officers were very poorly paid, so a chance of overtime was rarely turned down. Murders frequently made the difference for a young detective between having or not having a week’s holiday with his kids at Bridlington, Scarborough or Filey.

Every house within a half-mile radius of the murder scene was visited – without a breakthrough. So Hoban extended the search area by another half-mile. A twenty-year-old illiterate Irish labourer living with his wife in a corporation flat in Hunslet filled in a questionnaire that attracted attention. This former altar boy from County Wicklow, one of twenty-two children, learned many passages from the bible by heart, but he was a womanizer. He had been working on a sewer scheme near the murder scene and claimed that on the afternoon of the murder he saw a man running down Dewsbury Road. He identified the individual involved. But when the other man was checked, his alibi for the time of the murder was perfect – witnesses confirmed his presence in Leicester.

The Irish labourer had recently been released for larceny in Dublin and Hoban’s men were ordered to keep him under close observation day and night so he shouldn’t escape the net tightening round him. Finally, as is so often the case, forensic scientists provided the proof. Despite the fact that the man had washed his bloodstained clothing at his kitchen sink, the Home Office laboratory in Harrogate found thirteen fibres on trousers belonging to the suspect exactly matching those from clothing the victim was wearing when she was killed. Moreover, two hairs, similar in colour and appearance to those of the Irishman, were found on the dead woman.

Another protected inquiry masterminded by Hoban began on 2 April 1974, the day after Leeds City was amalgamated with the West Yorkshire force. Lily Blenkarn, an eighty-year-old shopkeeper known to everyone as ‘Old Annie’, had been brutally killed in a burglary that went wrong. She was severely beaten and suffered horrendous injuries, including a broken jaw and broken ribs. One fingerprint was found on a toffee tin and another on a bolt on the rear door of the premises, a sweet and tobacco shop in a terraced street. Hoban was convinced they belonged to the killer and organized a mass fingerprinting of all males in the area. They were invited to come to two local police checkpoints to provide their fingerprints.

It was the first major operation for the newly amalgamated force and it involved 150 detectives and the task force, a handpicked team of mobile reserves trained to work in major incidents. Some 24,000 people were interviewed in house-to-house inquiries, but some sixty men were unaccounted for. Some on the list had travelled abroad to Canada, Australia, Iceland and Hong Kong. Through Interpol they were traced and eliminated. The mass fingerprinting attracted huge media attention, including TV crews from America.

The killer turned out to be a cold, calm, sallow youth aged seventeen. He had persuaded a friend to give fingerprints in his place, allowing him to slip through the net. The one who impersonated him was the same who had given him an alibi early on in the inquiry. None of this came to light until the murderer gatecrashed a local party. When an argument ensued, he threw a brick through a window. Under arrest, his fingerprints were taken, and after a routine examination by the murder squad fingerprint experts they realized they had their man and someone must have impersonated the killer and given his fingerprints twice. Hoban said it taught him a valuable lesson. Never take anything for granted. ‘Should mass fingerprinting be required again – people would be fingerprinted in their own front room.’ It had been too easy for a killer determined to cover his tracks to collude with someone else to cover up his crime. Hoban’s inquiry had been thrown completely off the trail for a while.

Dennis Hoban’s bid to find the killer of Wilma McCann and Emily Jackson was an ambition that completely eluded him. He felt utterly frustrated, but he had other concerns. The huge volume of crime on his patch never stopped growing. Other women were randomly murdered in similar style and for a while he briefly flirted with the idea that the same man might have struck again. Then his handiwork was ruled out. The file on the McCann and Jackson murders remained open, but resources eventually had to be switched elsewhere. There was a horrible but unremitting truth he had to reconcile himself to: unless the killer struck again the chances of catching him were slim. So long as the murderer kept his head down, the investigation would go nowhere. Another poor unfortunate soul was probably going to die before this man could be put away.

3

‘A Man with a Beard’

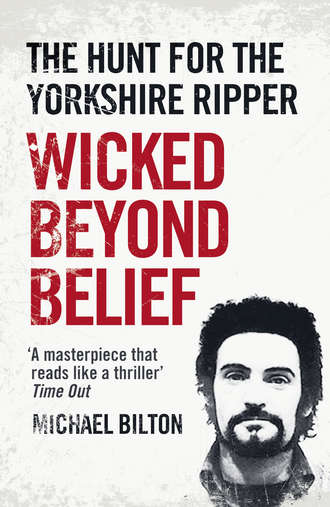

In 1963, a seventeen-year-old youth called Peter Sutcliffe appeared before local magistrates accused by Keighley Police of driving unaccompanied while being a provisional licence holder and for failing to display L-plates. There was a similar traffic conviction against him in May the following year at Bradford City Magistrates Court. They were the first of his eleven motoring convictions and an innocuous introduction to the judicial process. But a year later came a more serious encounter. Peter Sutcliffe’s first criminal conviction.

On 17 May 1965 he was fined £5 with £2 7s. 6d. costs at the Bingley West Riding Magistrates Court for attempting to steal from an unattended motor vehicle. The brown-eyed labourer, with black curly hair and (at that time) a fresh, clean-shaven complexion, had been caught ‘bang-to-rights’ trying to break into cars. It had happened on a quiet Sunday night the previous March, in Old Main Street, Bingley, beside the river Aire, not far from his home on the other side of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal at Cornwall Road, in the Gilstead area of Bingley. He and another youth, Eric Robinson, had been seen trying the door handles of a locked car that had property left on the rear seat. They were disturbed by two people who saw the pair then try the door handles of other cars parked near by. Police were called and a Constable Thornley quickly arrested the youth who would, ten years later, start a series of murderous attacks that became notorious in the annals of crime.

This conviction generated two separate official records: the first at the West Riding Regional Criminal Record Office at Wakefield, the second at the Central Criminal Record Office at New Scotland Yard in London. Each record detailed Sutcliffe’s name, age, date of birth, address, description and information about the offence. More motoring convictions followed in 1965 and 1966, but these were never filed at the criminal record offices.

The next recorded criminal violation by Peter Sutcliffe was during the early hours of 30 September 1969, in the Manningham area of Bradford, close to the city’s red-light district. He was seen late at night sitting in a motor vehicle deliberately trying to be unobtrusive, with the engine running quietly and the lights switched off. When a police officer called Bland approached the vehicle, Sutcliffe immediately drove off at high speed. A search was carried out and the officer later found the car unattended a short distance away. When nearby gardens were searched, Sutcliffe was caught and arrested. In his possession was a hammer.

Questioned by police, he could not provide a satisfactory explanation for having the hammer, but denied criminal intent. He was charged only with the banal offence of going equipped to steal rather than being in possession of an offensive weapon. We now know from Peter Sutcliffe’s own words that he fully intended attacking a woman that night, but the police had no inkling of this. Two weeks later he pleaded not guilty at Bradford City Magistrates’ Court, but the case against him was found proved by the bench and he was fined £25, to be paid at £2 per week. The West Riding CRO based at Wakefield and the Bradford City Police, which had its own separate criminal records office, both listed this offence in their files as ‘Going equipped for stealing’, whereas their counterparts in the Central CRO at New Scotland Yard in London made crucial reference to: ‘Equipped for stealing (hammer)’ and listed under the heading ‘Method’ the words: ‘In possession of housebreaking implement by night, namely a hammer [my italics]’. The Bradford criminal record office carried a passport-size head and shoulders photograph of the offender, whereas the West Riding CRO had three pictures of Sutcliffe in his file – one full length, one head and shoulders facing the camera, a third in profile. All three clearly showed Sutcliffe had dark curly hair, a dark-coloured beard and moustache.

For his next court appearance several years later, Sutcliffe presented the dapper and somewhat discordant colourful image for which he had become infamous within his circle of friends and family. He wore black trousers, brown platform shoes, a leather jacket with a multicoloured shirt and a red tie. By now he was married to the daughter of Czech émigrés and living with his parents-in-law at Tanton Cresent, Clayton, Bradford. He and a friend, Michael Barker, had stolen five second-hand car tyres worth 50 pence each from Sutcliffe’s employer, the Common Road Tyre Company, where he worked as a driver. Sutcliffe had been employed as one of the firm’s tyre fitters. On 15 October 1975, the company reported him to the police, claiming he had stolen tyres from them. When arrested and questioned Sutcliffe immediately admitted the offence and opened up the boot of his car to reveal his booty. By the time he appeared at Dewsbury Magistrates Court on 9 February 1976 to admit a charge of simple theft, Sutcliffe was already a double murderer. But there was nothing to connect him with those crimes. He was fined £25.

The name of Peter William Sutcliffe would not, in fact, feature among the complex index card system in the murder incident room of the West Yorkshire Police ‘Ripper Squad’ until November 1977. Even then he was the subject of only a routine inquiry. But the fact remains that by the summer of 1976 the ‘face’ of the man who had killed twice and would go on to murder another eleven women was buried in a filing system. With the benefit of hindsight we now know he was a serial killer, but successful murder investigations are not about hindsight. They are about foresight, hunches, risks, intuition, leadership, good communication and, of course, a series of standard operating procedures which involve the time-consuming task of knocking on doors, asking questions and comparing the answers with other information in police files.

Yet the ‘face’ of the Ripper, and clues to what he looked like, were lying hidden in the police files of investigations into unsolved, unprovoked assaults on women and a fourteen-year-old schoolgirl at various locations across West Yorkshire during the preceding three and a half years. The victims had been attacked in similar ways by assailants bearing roughly the same description. Tragically for the women Sutcliffe subsequently killed or attempted to kill, for their families and for the children made motherless over the succeeding years, most of these horrendous assaults were never linked as part of any series. More crucially, police ignored the descriptions provided by survivors who had given near-perfect illustrations and helped to prepare photofits of a dark-haired man with a moustache and beard who looked uncannily like Sutcliffe. But in 1976 there was nothing to point to him as being more than a petty thief. When the photofits are seen together today – alongside a police mugshot of Peter Sutcliffe taken in September 1969 – it all looks so blindingly obvious.

It was nearly teatime in Wakefield one day in October 1998. An attractive woman approaching middle age, but whose striking good looks and long dark hair made her appear years younger, answered a knock at her front door. She spoke a few words with a researcher from a documentary film-making company who had called at her home unannounced. Within seconds she was in a state of shock and a feeling of coldness started to overwhelm her. Suddenly she had a flashback at the mention of a terrifying incident that had happened to her twenty-five years beforehand. In the intervening years she had spoken about it to very few people, pushing the subject to the back of her mind. The woman had since married, had two teenage children, and wished to maintain her anonymity. She invited the researcher into her neat, well-kept home. Ushering her into the lounge, she said in her quiet Scots accent: ‘I was sure I had been attacked by the Yorkshire Ripper, but nobody had ever confirmed the fact.’