Полная версия

Fanny Burney: A biography

Boldness was not one of Charles Burney’s virtues. He dithered childishly about how to get out of the projected Italian tour, dropping hints to the Grevilles that he was in love, and looking gloomy. His child, a girl they named Esther, was born on 24 May 1749. Burney always doted on children, and perhaps the sight of his first-born and his vulnerable, patient mistress had a catalysing effect. He knew he couldn’t really leave them, and to introduce the subject in conversation with the Grevilles, he showed them the portrait of his sweetheart (not mentioning the baby, of course). There are indications that the aristocratic young couple found his melancholic behaviour a bit of a joke. Their light-hearted dismissal of his problem when it finally got an airing was to ask why he didn’t marry her. ‘May I?’ Burney asked, delighted at getting permission so easily. He and Esther were married the very next day, at St George’s Chapel, Hyde Park Corner, a popular venue for shotgun nuptials.

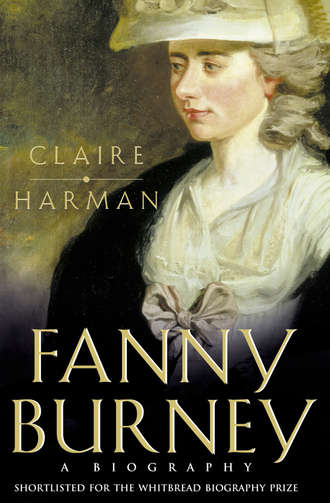

The critic Margaret Anne Doody has pointed out how significant this incident is in terms of Burney’s later example to his children, all of whom preferred devious or passive means of problem-solving to direct action. The idea of gaining permission and not offending one’s superiors became ingrained in the family ethos; as Doody says: ‘Charles was to inculcate in his children the pervasive dread of offending someone whose permission should be asked, and he indicates some unwitting enjoyment of being the person who had power to give or withhold permission from his children, the only group to whom he could give it and to whom he need not apply for it.’31 This ‘pervasive dread’ was felt most sharply and most destructively by his second daughter, Fanny. Even when she was sixty-two years old, Fanny did not dare address her father ‘contrary to orders’ as he lay dying: ‘[t]he long habits of obedience of olden times robbed me of any courage for trying so dangerous an experiment’.32

When the Grevilles went off to Italy in the summer of 1749, Burney was left to fend for himself and his young family. He had not lost Greville’s goodwill, but the patronage had gone, and from the splendours of Wilbury House Burney had to adjust to life as organist of St Dionis’s Backchurch in Fenchurch Street. He had taken over payment of the rent on Mrs Sleepe’s fan shop at Easter 1749, and may have been living there with Esther as man and wife some time before their wedding in June. His father died around the same time, and it was perhaps as early as this year that his mother and sisters Ann and Rebecca came from Shropshire to live over the shop at Gregg’s Coffee House in York Street,* run by a kinswoman, Elizabeth Gregg. Female dependants became, from this period onwards, a given of Charles Burney’s life. He was earning a tiny salary of £30 per annum from St Dionis’s and had to supplement it with odd jobs of teaching and composing (his first published song was to words by his friend the poet Christopher Smart).

One of his pupils was the Italian opera singer Giulia Frasi, at whose house and at the Cibbers’ Burney used to meet George Friedric Handel. Burney revered Handel’s music and, starstruck, had shadowed the great man round Chester once in his youth. On closer acquaintance, some of the glamour necessarily faded. Handel was short-tempered and extremely impatient of mistakes, bawling at Burney for singing a wrong note in one of Frasi’s lessons, as Burney recalled in his memoirs:

[…] unfortunately, something went wrong, and HANDEL, with his usual impetuosity, grew violent: a circumstance very terrific to a young musician. – At length, however, recovering from my fright, I ventured to say, that I fancied there was a mistake in the writing; which, upon examining, HANDEL discovered to be the case: and then, instantly, with the greatest good humour and humility, said, ‘I pec your barton – I am a very odd tog: – maishter Schmitt is to plame.’33

Burney was to meet a great many famous men on his way to becoming one himself, and had stories about most of them. Like his father before him, he knew the value of a good stock of anecdotes and told them well – comic voices included. He intuited that the ability to converse, to tell stories and (perhaps most importantly for his later connection with Dr Johnson) to listen was going to be his surest way to earn and keep a place in the influential company he craved. Fanny Burney thought her father’s written reminiscences did no justice to his anecdotal powers, or the charm and wit of his conversation, that they constituted ‘little more than Copying the minutes of engagements from his Pocket Books’.34 She was clearly disappointed that he hadn’t left anything more solid for posterity to marvel at, but for Charles Burney the primary function of his stories (which drip with dropped names) was to make an immediate impression on a live audience.

With his patrons abroad and his responsibilities multiplying, the better life that Burney wanted for himself and his family seemed to be receding from his grasp in the early 1750s. Esther had given birth to two more children, James in June 1750 and Charles the year after. In order to keep the household going Burney pushed himself to do extra teaching, as well as playing in the theatre band almost every evening and composing. His rewriting of Arne’s Masque of Alfred had its first performance in February 1751 at Drury Lane, a momentous occasion for the twenty-four-year-old musician, but one he couldn’t attend because of a prior engagement at a subscription concert. ‘I fear my performance there was not meliorated by my anxiety for the fate of my Offspring at Drury Lane’, he wrote:

I hardly staid to play the final Chord of the last piece on the Organ, ere I flew out of the concert-room into a Hackney coach, in hopes of hearing some of my stuff performed (if suffered to go on) before it was finished; but neither the coachman nor his horses being in so great a hurry as myself, before I reached Temple bar, I took my leave of them, & ‘ran like a Lamp-lighter’, the rest of the way to the Theatre; and in a most violent perspiration, clambered into the Shilling Gallery, where scarcely I cd obtain admission, the rest of the House being extremely crowded, wch did not diminish the sudorific state of my person. I entered luckily, at the close of an Air of Spirit, sung by Beard, which was much applauded – This was such a cordial to my anxiety & agitated spirits, as none but a diffident and timid author, like myself, can have the least conception.35

The impatience with the hackney coach, the muck sweat, the obscurity of the Shilling Gallery and the sense of eavesdropping on his own work’s first performance all seem to typify the urgency, anxiety and effort with which Burney strove to establish himself in the world. His work habits became almost manic; he pushed himself to the point of collapse, and then sank into protracted illnesses. In the winter before the debut of Alfred, he spent thirteen weeks in bed, a disastrously long time for a breadwinner, and certain to have agitated his restless mind. He was a small, very thin man, whose constitution was in fact as strong as an ox but who looked as if he might turn consumptive with every passing chill. In this, as well as in frame and feature, his second daughter was to resemble him closely.

The illness of 1751 must have alarmed Burney considerably. A short convalescence in Islington (then a balmy village) made him begin to credit his doctor’s insistence that he seek a permanent change of air. Reluctantly, he began to think of leaving the capital. When the offer of the post of organist at St Margaret’s Church in Lynn Regis, Norfolk, came up, combining sea air, light duties, a much larger salary and, since 1750, a regular coach service to London (splendidly horsed and armed to the teeth with muskets and bludgeons), it would have been folly to refuse. Burney moved there alone in September 1751 ‘to feel his way, & know the humours of the place’.36

Lynn Regis (now known as King’s Lynn) was a thriving mercantile centre in the mid-eighteenth century, with valuable wine, beer and coal trade and corn exports worth more than a quarter of a million pounds a year. It supplied six counties with goods, and sent river freight as far inland as Cambridge. The wealthy aldermen of Lynn were keen to improve the cultural life of the town and to acquire a good music-teacher for their daughters; to this end they had increased the organist’s salary by subscription to £100 a year in order to attract Burney (clearly some influential friend or friends had a hand in setting this up), and were prepared to raise the pay even further when they feared they might lose him.

Burney at first resented his provincial exile: the organ in St Margaret’s was ‘Execrably bad’ and the audiences as unresponsive as ‘Stocks & Trees’,37 but over the months his attitude changed. He began to be patronised by some of the ‘great folks’ of north Norfolk – the Townshends at Raynham, the Cokes at Holkham Hall, the Earl of Buckinghamshire at Blickling, Lord Orford (Horace Walpole’s nephew) at Houghton – and his spirits rose. All these grandees had large estates, beautiful grounds, art collections and libraries. Burney found that in Norfolk there might be, if anything, even more influential patrons at his disposal than in London, and that the burghers of Lynn were prepared to treat him as the ultimate authority on his subject. Soon he was writing to Esther in encouraging tones. Pregnant for the fourth time, she and the three children joined him in the spring of 1752, and it was probably at their first address in Lynn, Chapel Street, that their daughter Frances was born on 13 June. The new baby was baptised on 7 July in St Nicholas’s, the fishermen’s chapel just a few yards away, with Frances Greville, returned from the Continent, named as godmother.

The choice of Mrs Greville helped re-establish Charles Burney’s connection with his former patrons, but it also had a literary significance, since Mrs Greville was not just a formidable intellectual but an accomplished poet, whose ‘Prayer for Indifference’ – published in 1759 – became one of the most famous poems of its day. The Burneys must have expected something substantial to come of the connection, for Fanny’s sharp judgements of her godmother both personally – she thought Mrs Greville ‘pedantic, sarcastic and supercilious’38 – and as a godparent – ‘she does not do her duty and answer for me’39 – betray more than pique.

The modest provincial household into which Mrs Greville’s namesake, Frances, was born was bent on intellectual improvement; Charles and Esther Burney had set themselves a course of reading in the evenings which included ‘history, voyages, poetry, and science, as far as Chambers’s Dicty, the French Encyclopédie, & the Philosophical transactions’.40 Not many young couples went to the expense of subscribing to the first edition of Diderot’s Encyclopédie, and not many Lynn housewives would have relished reading it of an evening, but Esther Burney was an earnest autodidact, ‘greatly above the generality of Lynn ladies’,41 whose card-playing evenings bored her, and whom she was soon making excuses to avoid. Esther was a city girl, born and bred, and was probably keener even than her husband to get back to London. He had his teaching and the great houses to visit; she had four young children to look after in an unfamiliar provincial community. As their daughter was to observe later: ‘That men, when equally removed from the busy turmoils of cities, or the meditative studies of retirement, to such circumscribed spheres, should manifest more vigour of mind, may not always be owing to possessing it; but rather to their escaping, through the calls of business, that inertness which casts the females upon themselves’.42

Esther found two like-minded women in Lynn during her nine years’ residence there, Elizabeth Allen and Dolly Young, with whom she formed a sort of miniature literary salon. They met regularly at the house of the richest, most beautiful and most voluble of the three, Mrs Allen, a corn merchant’s wife, who had a ‘passionate fondness for reading’ and ‘spirits the most vivacious and entertaining’.43 Dolly Young was nearer to Esther in temperament; studious and sensitive, she became Esther’s particular friend, and a sort of aunt to the children, several of whom, including Fanny, she helped deliver. Unlike her two married friends, Dolly Young was not at all beautiful; her face had ‘various unhappy defects’ and her body was ‘extremely deformed’44 (almost certainly through smallpox) – an odd companion for Mrs Allen, who was widely regarded as the town’s great beauty. Charles Burney admired all three: ‘I thought no three such females could be found on our Island’, he wrote later, noting with approval, ‘They read everything they cd procure’.45

Only a few months after baby Frances was born, her year-old brother Charles died and was buried on the north side of St Nicholas’s. Esther was soon pregnant again, but this child, also named Charles, did not survive infancy. Her sixth child, a daughter christened Susanna Elizabeth, was born in January 1755, a frail baby who was lucky to escape the smallpox outbreak that lasted in Lynn from 1754 to 1756. There were so many deaths during this period that St Margaret’s churchyard was closed due to overcrowding, and the hours of burial had to be extended from 8 a.m. to 9 p.m. each day to cope with the demand. Typhus outbreaks were also common in Lynn, and Charles Burney must sometimes have wondered if the ‘change of air’ for which he had left London was going to cure him or kill him.

By the mid-1750s the Burneys had moved to a house on the High Street, near to stately old St Margaret’s Church and in sight of the masts of the ships docked on the Great Ouse. It was a just a few minutes’ walk to the foreshore, where the children could watch the traffic on the river. The waterfront was full of warehouses with watergates to let small boats in at high tide, and the quays were always busy, with coal and wine and beer being loaded, or the fishing fleet bringing cod and herring in. Salters and curers’, shipbuilders’, sail and ropemakers’ premises lined the docks, with their noise and smell of industry. Once a year, in July or August, the whaling fleet came in from its far journey to Greenland, the decks laden with monstrous Leviathan bones. The bells of St Margaret’s would peal in celebration and the town enjoy a general holiday, for Lynn was proud of its mercantile nature, never mind the reek from the blubber houses as the rendering process got under way, or the stench of the Purfleet drain at low tide.

Fanny Burney, like her mother, was essentially a city-lover, and spent most of her adult life living right in the middle of London or Paris. Her childhood in Lynn was happy because she was constantly in the company of her ‘very domestic’ mother46 (who nursed the children herself) and adored father, but country-town life does not seem to have appealed to her imaginatively, and she avoided writing about it. Spa-towns, seaside towns, rural retreats and, most of all, London, appear in her novels time and again, but workaday places like Lynn get short shrift. ‘I am sick of the ceremony & fuss of these fall lall people!’ she wrote when visiting Lynn Regis as a young woman. ‘So much dressing – chit chat – complimentary nonsence. In short, a Country Town is my detestation. All the conversation is scandal, all the Attention, Dress, and almost all the Heart, folly, envy, & censoriousness. A City or a village are the only places which, I think, can be comfortable, for a Country Town has but the bad qualities, without one of the good ones, of both’.47

The Burneys’ was a self-contained and self-sufficient household. Charles Burney had stools placed in the organ loft of St Margaret’s for his family, from which they could look down on the rest of the town during services. Esther did not mix much with the local women and educated her children at home, except for James, who had a couple of years at the grammar school on grounds of his gender. Hetty was the child who showed greatest promise, both intellectually and musically. Even as a small girl, it was clear she had the makings of a first-class harpsichordist, and attention was lavished on her by both parents. Fanny, who showed no special ability at anything and no inclination to learn to read, was left to develop in her own time. There was always a baby to play with: another son christened Charles was born in December 1757, when Fanny was five and Susan almost three. An eighth child was born in late 1758 or early 1759, and christened Henry, but he died in 1760. Fanny had been too young to remember the death of the second baby Charles, but was turning eight when Henry died.48 It must have affected her sadly, she was known as a ‘feeling’ child, of the most delicate sensibilities towards all living creatures.

Fanny Burney’s intense admiration for her father had its roots in these early years in Lynn. In such a community, a talented, energetic and ambitious man like Charles Burney was treated with enormous respect. He persuaded the corporation to have St Margaret’s ‘execrable’ organ cleaned, and when it fell apart in the process, got them to have a brand new one built, on which he performed dazzlingly various pieces of exciting contemporary music, such as Handel’s Coronation Anthem. Charles Burney’s playing in church, Charles Burney’s subscription concerts and Charles Burney’s evening parties were the best by far (there was no competition) in a town Fanny described as culturally in ‘the dark ages’.49

But however popular he was in Lynn, Charles Burney never intended to stay there very long, and the children must have got used to their parents talking about London as if it were their real home. Burney made a couple of attempts to leave during the 1750s, but his obligations (and some strategic salary hikes) kept him in place. His noble patrons made him feel valued and full of potential; Lord Orford was particularly generous, and allowed the musician the run of his library at Houghton. Burney would get the key from the housekeeper and wander around when the master was absent, no doubt fostering fantasies of one day possessing such a library and such a lifestyle himself. Early on in his Norfolk days, Burney had bought a mare called Peggy on which to travel the long distances from Lynn to his aristocratic and county clients, and typically he made use of the time spent on horseback (she was obviously a very trustworthy animal) teaching himself Italian from the classic authors, with a home-made Italian dictionary in his pocket. He bore all the marks of a man in training for something greater. His mind was turning to literary schemes, and perhaps it was as early as in these years that Burney first conceived his plan to write a history of music, something monumental in the style of Diderot’s Encyclopédie or Samuel Johnson’s new Dictionary of the English Language, to which he was also a subscriber. He kept himself in touch with the musical and intellectual life of London by going to town every winter. He hardly needed the urgent advice of his friend Samuel Crisp, whom he had met through the Grevilles:

is not settling at Lynn, planting your youth, genius, hopes, fortunes, &c., against a north wall? […] In all professions, do you not see every thing that has the least pretence to genius, fly up to the capital – the centre of riches, luxury, taste, pride, extravagance, – all that ingenuity is to fatten upon? Take, then, your spare person, your pretty mate, and your brats, to that propitious mart, and, ‘Seize the glorious, golden opportunity,’ while yet you have youth, spirits, and vigour to give fair play to your abilities, for placing them and yourself in a proper point of view.50

By 1760, Burney felt he had fulfilled his obligations to the ‘foggy aldermen’ of Lynn Regis. He decided to move his growing family back to London, ostensibly to further their chances in life, but more immediately to further his own. James, an easy-going boy who had not shone at school, was not to accompany them. It was agreed that he should join the navy, and he was signed up as Captain’s Servant on board the Princess Amelia. This was a recognised way for poorer boys to get some rudimentary officers’ training, but it was also an abrupt and dangerous introduction to adult life for a ten-year-old, and one wonders why his parents submitted him to it. Perhaps their ignorance of seafaring was as great as their backgrounds suggest. The Princess Amelia was a man-of-war, a huge floating artillery, with eighty cannon and 750 men on board, a far cry from the fishing boats and merchantmen James might have watched sailing up the Great Ouse. The Seven Years’ War was at its height, and the Princess Amelia was on active service: the year James joined the crew, it formed part of Hawke’s squadron in the Bay of Biscay and was almost blown up by French fireships in the Basque Roads the following year. News from the war took a long time to reach England, and the Burneys would have had little idea of the danger their son was in until it was well past. James’s career would keep him out of family life all through his formative years, and, not surprisingly, his own later behaviour as a family man was eccentric, to say the least. The violent contrasts between home life and the sea must have made the former seem vaguely surreal to him; he didn’t let one impinge on the other, and it is doubtful that his family ever understood the privations or excitements of his day-to-day existence.

The Burney family made their momentous move to London in September or early October 1760, to a house on Poland Street in Soho, a significantly better address than Charles Burney’s last one in the City. Soho, which had been very sparsely inhabited up to the sixteenth century but heavily developed by speculators after the Great Fire, was new and fashionable. The elegant squares and streets that spread their gridwork across the fields, the former military yard and around the old windmill* contained rows of houses quite different from the ‘Cottages … Shedds or meane habitacons’ that had straggled there as recently as 1650.51 Poland Street had been begun in 1689 and named, topically, in honour of John Sobieski’s intervention against the Turks at the siege of Vienna. It wasn’t one of the best addresses in the area – Leicester Fields, Golden Square and King’s (later Soho) Square had far more aristocratic associations – but it was a very respectable one for an ambitious music-teacher. Soho was full of middle-class families providing services to the rich: Huguenot craftsmen and jewellers, German instrument-makers, gun-makers, portrait-painters, wine merchants, watchmakers, architects and medical men. Next door to the Burneys was a hair-merchant who made wigs for the legal profession, a specialised business with dignified associations. The children of the two households played together in the little paved yards behind the properties.

By the time Fanny Burney was writing the Memoirs in the late 1820s, she was aware that her readers might be unimpressed by the family’s former address, ‘which was not then, as it is now, a sort of street that, like the rest of its neighbourhood, appears to be left in the lurch’.52 She stressed how genteel Poland Street had been in the 1760s, when the Burneys had lords, knights and even a disinherited Scottish Earl for neighbours, and exotic visitors such as a Red Indian Cherokee chief who was staying in a building almost opposite number 50 and whom the Burney children watched come and go with awed delight.

The contrast with Lynn was dramatic, the scope for entertainment and amazement seemingly endless. Though there were still fields and allotments a stone’s throw away in the undeveloped land to the north of Oxford Road (now Oxford Street), London was full of shows and spectacles guaranteed to impress young children straight from the provinces. The theatre at Drury Lane was well known to them through their father’s long association there with Arne and his friendship with Garrick; they also knew the rival theatre at Covent Garden and the splendid opera house in the Haymarket, which had room for three thousand spectators (about a third of the population of Lynn Regis). London was filling up with teahouses, coffee houses, strange miniature spas, assembly rooms, puppet shows and curiosity museums to cater for the leisure hours of the rapidly expanding metropolitan population.